The election that changed football: when Joao Havelange unseated Sir Stanley

Joao Havelange’s unseating of Sir Stanley Rous as FIFA President in 1974 precipitated a period of politics, pound signs and power struggles

Sir Stanley Rous woke early on the morning of June 11, 1974, opening his hotel room curtains as the rest of Frankfurt slept. He was greeted by a slate grey sky emptying torrential rain on a city readying itself for a FIFA Congress that would shape the future of football.

The previous day had been a good one for the man the Daily Mirror referred to as ‘Mr World Football’. A last-minute shoring up of his support from Asia and a number of African countries had, he hoped, breathed fresh life into the campaign to continue his 13-year reign as the most influential man in the global game.

“Sir Stanley Rous was winning fresh support here last night in his bid to stay President of FIFA,” wrote John Jackson, the Mirror’s man in Frankfurt.

NEWS Former FIFA president Havelange dies at 100

After a presidential campaign that had spluttered into life only intermittently, Rous, 79, knew as he strode purposefully down to breakfast that he faced an ominous opponent who was determined not only to strike a blow for South American football, but also to reshape the global game.

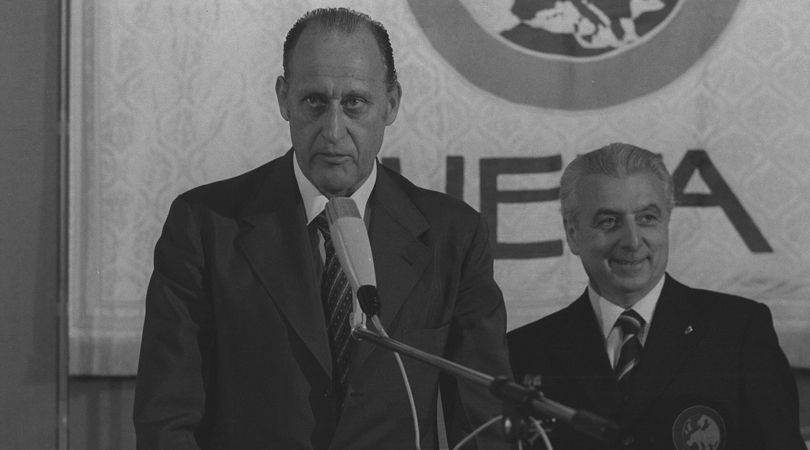

That opponent’s name was Joao Havelange, a 58-year-old Brazilian former Olympic swimmer, but now a millionaire businessman and consummate politician who could sense that history was about to be made. As Rous sat, straight-backed with a cup of English breakfast tea in front of him, he had a similar feeling. Change was in the air.

Sepptic

It had been 40 years since an incumbent FIFA president was unseated from his job before Sepp Blatter was finally forced out after 17 years in the hot seat in late 2015.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The widespread disaffection with Blatter’s reign had become increasingly clear since the last presidential election was held in 2011, with the muddied waters surrounding world football’s governing body becoming ever murkier as a man earmarked for the presidency long before his 1998 accession has lurched from one controversy to another.

We can only guess what Rous would have made of it all, but his former personal assistant, Rose-Marie Breitenstein – who worked with Rous almost continuously from 1961 to his death in 1986 at the age of 91 – gives FourFourTwo a good idea. “Sponsorship came into the game [during Rous’ reign in charge of FIFA] but he wasn’t a financier; he was a former schoolmaster,” she says.

“His interests were in education, and finance was not quite his forte. I think with the sponsorship and the money involved, he would not like that at all. I don’t think he’d be very fond of the game now, because that’s what he thought it was – a game, played for recreation and enjoyment.”

Rous the ref

Those beliefs were formed through an extraordinary career that saw Rous go from serving in Africa during the First World War to teaching at Watford Grammar School. With England leaving FIFA during his time in the classroom in 1928, it seemed an unfeasibly remote prospect for him to one day lead football’s most powerful organisation.

The same could not be said of his rival in the 1974 election, the Rio-born son of an arms dealer, who set his sights on power and wealth at an early age. What they did share was a love of football, although Rous’ interests were more diverse than those of Havelange.

Rous played for St Luke’s College in Exeter and then for the army during the Great War. He could, it was thought, have been good enough to forge a career in the Football League – though this very English gentleman would have given short shrift to the thought of playing professionally.

“His real love, his real passion, was refereeing,” says Breitenstein. “He probably did more than anyone else to develop the standards of officiating around the world.”

Rous would referee the 1934 FA Cup Final between Manchester City and Portsmouth before hanging up his whistle to concentrate on football administration. Just two years later, his future rival for the presidency would board a plane bound for Berlin as part of the Brazilian Olympic swimming squad.

It was in the pool, not on the pitch, that the former Fluminense youth-team player thrived, with the Brazilian taking part in the 1936 Games hosted by Adolf Hitler’s Germany, before also competing in water polo at the Helsinki Olympics in 1952.

Speaking to John Sugden and Alan Tomlinson in Badfellas: FIFA Family at War, Havelange gave an insight into the competitive nature that would serve him so well, in and out of office. “Water polo served to discharge my aggressiveness and all my occasional ill-humour,” he said.

His polar opposite in attitude and outlook, Rous had long been aware of South America’s desire for change. Speaking to The Times in Rio in July 1972, however, he believed any challenge to be some way off. “I shall certainly stand again,” he said, “provided, of course, that I am still in good health and feel that I can still do a good job – that I’m not too doddery to continue.

“After I had been re-elected two years ago, the South Americans made it quite clear that they would like Mr Havelange to succeed me at the earliest opportunity. And I feel quite sure that, from a prestige point of view, they would like at some time to have a South American president. They probably will when I’ve gone – but I haven’t gone yet.”

When Havelange did finally take the decision to stand – with only neighbouring Argentina reluctant to officially sanction his bid – he travelled to London to meet Rous. As they sat down for dinner, the Brazilian businessman told the ageing Rous that if he stood there would “only be one winner”.

“He put his arm around me, like a father would his child,” Havelange later recalled. “I don’t think he believed me.”

A very different world

At the last World Cup in Brazil, FIFA reportedly enjoyed revenues of $4.4 billion, with profits of $2bn. World football’s governing body is, in short, a modern-day money-making machine.

In Rous’ day, the organisation – and the World Cup itself – was anything but. “He worked from home,” says Breitenstein. “He would travel to Switzerland fairly regularly but he would spend most of his time either working from London or travelling the world.”

By 1974, little had changed. “Operating from its modest headquarters in Zurich, it was little more than a one-man operation run on a shoestring,” wrote Sugden and Tomlinson. “The organisation had fewer than a hundred members and operated one tournament only, the World Cup finals, for which only 16 nations could qualify to take part.”

Although the exclusive nature of that competition ensured that Europe remained the dominant force in global football, what it also did was foster resentment in parts of the world that felt marginalised by FIFA in general and Rous in particular.

It was his attitude to South Africa – the bane of sporting administrations across the world during the apartheid period – that provided him with his biggest problem (and Havelange’s most potent weapon).

The situation in a country which forbade the majority black population from playing football alongside South Africa’s white ruling class was a complicated one, and Rous manifestly struggled to deal with it. He was perceived as out of touch with the realities of African politics.

Their membership of FIFA was a political hot potato throughout the 1960s and Rous’ approach did him few favours. Suspended from the organisation in 1961 as a result of apartheid, South Africa’s Football Association (SAFA) were re-admitted two years later after a FIFA investigation led by Rous into the SAFA’s claim that they were committed to inclusivity.

This wasn’t popular across the rest of the continent, and with the newly formed Confederation of African Football (CAF) already incandescent at the allocation of just one place to countries in Africa and Asia-Oceania at the 1966 World Cup, ill-feeling grew between Africa and a body regarded as colonialist and pro-European. Things were hardly helped by a letter penned in 1963 by Dr Helmut Kaeser, FIFA’s General Secretary, which accused CAF of following a policy line which carried “a germ of despotism and dictatorship”.

“There was a strong sense across a lot of the football world that the game was a European venture and that FIFA should really operate in the interests of the European game and the European football nations,” says Paul Darby, author of Stanley Rous’ ‘Own Goal’: Football Politics, South Africa and the Contest for the FIFA Presidency in 1974.

“There was a desire to ensure that that remained the case. Any time the African nations sought to use FIFA or world football as a vehicle for registering their presence on the international stage, they were met with resistance and narrow European self-interest.”

Breitenstein, however, insists that Rous’ stance was not to do with any desire to maintain the status quo, but rather a deep-seated commitment to meet every challenge with a straight bat. “He always said that football and politics shouldn’t mix,” she says. “He stuck to the rules.”

That meant precious little to the 15 countries who decided that the only way to make FIFA sit up and take notice was to boycott a World Cup. That intention was lodged at the FIFA congress in Tokyo in October 1964 and carried out to the letter by CAF’s disillusioned membership.

Rous also had his critics closer to home. In the technical report compiled after the 1966 World Cup, Switzerland’s Italian coach Alfredo Foni wrote: “The Jules Rimet Cup will have attained its aim only when the five continents are effectively represented – football probably being the most universal of all sports.”

South America takes a stand

As 1974 dawned, Havelange was on the front foot, with his election campaign moving at a speed that left Rous standing. Before June’s FIFA Congress, he would visit 80 different countries, promising investment in stadiums, infrastructure improvements and, crucially, greater representation at world football’s showpiece event.

“It is a quest for new power on the part of a challenging activist who has spread largesse liberally in many quarters in an effort to win support in bringing down the establishment,” wrote Geoffrey Green in The Times. “In short, it is Europe versus the rest.”

In the run-up to the vote in West Germany, there were rumours of a potential split in the governance of northern and southern hemisphere football, but in the corridors of power at the Football Association there was a real concern that a vote for Havelange would result in the end of English football having a seat at the top table of the game.

In Paris in the summer of 1972, Uruguay had tabled a proposition calling for the four seats enjoyed by the Home Nations to be cut to one – a natural precursor to the unification of the quartet on the world stage, which in turn would free up more World Cup places for countries elsewhere.

“It was potentially the most explosive proposition facing Congress for many years,” reported Reuters. “The four UK countries were believed to be prepared to walk out of FIFA, probably taking some other countries with them, if a vote went against them.”

While that threat was averted, Rous cut himself further adrift from South America by insisting that the executive committee vote against plans to extend the World Cup from 16 to 24 teams for Argentina in 1978.

With South America well and truly on his side, Havelange then looked on in a mixture of amazement and glee as Rous made a mess of a play-off between Chile and the Soviet Union in November 1973 for a place at the following year’s World Cup.

With General Augusto Pinochet using the national stadium in Santiago as an internment camp for those who opposed his regime – it was apparently the location for executions in the run-up to the match – the Soviet Union, understandably, called for the match to be switched to a neutral venue.

Rous refused, so the Soviets – already the underdogs after a 0-0 draw in the first leg of the play-off in Moscow two months previously – stayed at home. As Pinochet and his cronies cleared the pitch and the changing rooms of up to 1,700 political prisoners, it was left to Chile to kick off against an absent opposition.

A statement from the Soviet Football Federation accused FIFA of “supporting Chilean reaction” as a result of its insistence that the match go ahead. FIFA had, the Soviets said, refused “to take into account the bestial crimes known to the whole world”.

This drip-drip of bad news and rank poor governance appeared to be getting to Rous. Addressing UEFA in Edinburgh three weeks before the ballot, Rous finally shed his stiff upper lip to appeal to his European allies. “Vote for me because it is Europe versus South America and we want Europe to retain the leadership of football,” he said. “If I am elected for a further term, you should immediately look for a successor from Europe so that this European leadership is maintained.”

To many onlookers, though, it looked like a desperate last throw of the dice.

Stanley's last stand

As the delegates filed into the smoke-filled Congress hall, journalists from across the world gathered, sensing that one of football’s most seismic shifts was about to become a reality. While Havelange whirred around the room, confirming his support, Rous merely asked people to consider his record from more than a decade in office before voting.

“I can offer no special inducements to obtain support, nor have I canvassed for votes,” he said. “I prefer to let the record speak for itself.”

These final comments revealed just how far behind Rous had fallen in the election race. The Brazilian challenger was, however, forced to wait before the celebrations could really begin. The first round of voting produced no winner, with Havelange needing a two-thirds majority for victory but succeeding only in edging out Rous by a small margin.

Even though the second vote required merely a straight majority, Havelange was perpetual motion, darting between delegates to shore up his support. Around vast tables encircling the room, delegates sat with headsets, listening to events unfold. Rous sat impassive, sipping at a drink as the votes were cast.

After FIFA’s global membership had visited the ballot box for what would be the final time, the results were announced: the Brazilian had 68 votes to Rous’ 52, more than he needed to dethrone a man viewed as bomb-proof by the British press, the FA and UEFA. Power had been torn from Europe’s grasp for the first time since FIFA was formed in Paris in 1904.

“I soon adjusted myself,” said Rous when later quizzed about the 1974 election by the BBC’s Peter Jones. Privately, he admitted the defeat was a devastating blow.

“It was a blow to him but he didn’t show it,” says Breitenstein. “I think, somehow, it may have hurt him a bit, yes, but he had to carry on because there was the World Cup still. He went on with the work because he was still responsible for the 1974 tournament.”

The final insult, fittingly, was proffered by Havelange, who gave Rous a kiss and handed him a large bunch of flowers. “For them they are a bouquet, while mine is more in the nature of a wreath,” said Rous. “It will be difficult to realise I’m no longer president.”

In a mirror of the allegations that would come to haunt FIFA in the future, the Daily Express focused on Havelange’s apparent decision to pay the travelling expenses of 30 delegates “representing between eight and 10 African nations”. It was, the paper noted, a “perfectly legitimate” way of ensuring he got the votes he required. The pockets of Rous, however, weren’t anywhere near as deep.

Rous would never have been so crass as to suggest that money had eventually swayed the outcome of the election, but he could clearly see the direction in which his opponent wanted to take the game. “The trends in world football are not too pleasing at the moment, and after today’s meeting I will be better out of the way,” he lamented.

Now, more than 40 years on, the distrust of FIFA is greater than ever – although it now emanates from Europe rather than Africa and Asia.

This feature originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!