Euro 96, the complete history, part one: England's expectations, the dentist's chair and El Tel's troubles

The iconic Euro 96 tournament holds a special place in our hearts, but with tabloids and parliamentarians turning on the team, it had difficult beginnings

This is part one of this feature: Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

You know the story of Euro 96, don’t you? A footballing opera played out against a backdrop of endless summer, accompanied by a timeless theme song, with cameo roles for great goals and that most enduring of central themes: England coming up agonisingly short (even before the tournament began, it was “thirty years of hurt”).

Except, as is so often the case, the pocket opera tells only half of the story. Euro 96 was far more nuanced and more complicated than that. Albeit not on this subject, Charles Dickens penned: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” - and that was Euro 96.

It had its highs, which fed into an oversimplified shorthand; it also had its lows, which did the same. It certainly had stories which struggle to be heard now. Some of what you may know is wrong – even England’s formation. This can be the effect of history’s telescoping as events disappear into the rear-view mirror.

VIDEO: Why England's EURO 96 Team Was So Far Ahead Of Its Time

Because many of the dramatis personae still stalk the stage of our football theatre – from Southgate to Shearer and Gazza to G-Nev, not to mention your Baddiels, Skinners and Gallaghers in the audience – it feels like only yesterday. But it isn’t. It’s now further from the present than it was from the Three-Day Week, the Vietnam War, the opening of the Sydney Opera House and the eradication of smallpox.

This was A Different Time. From our vantage point now in what was then the distant future (Blade Runner, featuring its synthetic humans bio-engineered to work on colonies in space, was set in 2019), the biggest single difference was the lack of internet. Only two per cent of Britain had a reliable regular connection. Very few people had mobile phones at all, let alone perma-networked smartphones. The nearest thing to social media was graffiti. Or the pub.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Having a focused audience gave immense power to the few. Piracy was limited to taping so overpriced CDs sold in millions, helping to turbocharge an industry and make pampered princes of its big names. Given little choice, the public had to want what the public got. Sky did make a splash with the Premier League but still only one in 10 Brits had satellite or cable. The vast majority, unable to see Kelvin MacKenzie’s L!ve TV, including its topless darts and weather forecasts presented by trampolining dwarves, made do with four terrestrial channels.

The war between tabloids was at its peak, as the Mirror, under a tryhard called Piers Morgan, attempted to catch The Sun. Every paper loved the prurient no-you-mustn’t-look coverage of ‘scandal’, and the national pastime: slating the England team. They often had good reason to.

"We were a joke. People were laughing at us"

Venables' legal battles involved Alan Sugar, Panorama, Scotland Yard, the Mirror, bung allegations (unproven), and a judge describing him as “not entirely reliable”. A Labour MP used parliamentary privilege to call him unfit for the job

Revisionist history suggests England went into Euro 96 confident, but they did not. From this distance – there’s that telescoping again – the semi-final campaigns of the 1990 World Cup and Euro 96 are near-neighbours, but a turgid half-decade separated them: Graham Taylor’s one-dimensional embarrassment of a side was gormless at Euro 92, absent from USA 94.

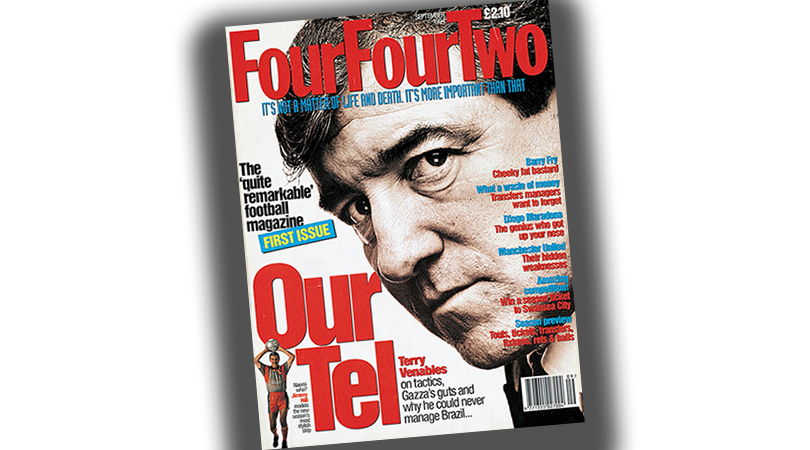

Enter Terry Venables, who knew the size of the task facing him upon becoming England’s first head coach – some at the FA didn’t want him to be ennobled with the title of ‘manager’ – in January 1994.

As someone who had been abroad without packing baked beans and fish fingers, the former Barcelona manager was well aware of England’s isolationism – ‘El Tel’ told FourFourTwo just before Euro 96, “I was at a conference in Sweden a few years ago and we were a joke. People were laughing at us, at our tactics.” He installed a keenness to learn.

Public enthusiasm remained low, however. Automatic qualification as hosts meant two years of pre-Euro 96 friendlies which brought pressure without pleasure. Alan Shearer noted: “England don’t have friendly matches. If you play badly, you’re going to get hammered.”

Most were held at an echoing Wembley. Just 23,000 saw Venables’ second game, against Greece. England did venture abroad as far as Dublin and lasted as long as 27 minutes, until rioting idiots forced the tie to be abandoned.

Off the field, Venables wasn’t to everyone’s taste. MP Kate Hoey, never shy of a soapbox, used parliamentary privilege to call him unfit for the job. His various legal battles – which involved Alan Sugar, Panorama, Scotland Yard, the Mirror, bung allegations (unproven), a judge describing him as “not entirely reliable” and the Department of Trade and Industry starting proceedings to disqualify him as a director – became tabloid fodder.

The East Ender struck several FA suits as a little too wide for their narrow idea of an England gaffer. Contracted until Euro 96, Venables requested an extension but the FA could not uniformly agree upon it; bizarrely, he was offered until halfway through the next World Cup qualification campaign. In January 1996, he declared his intention to leave after Euro 96 whatever the outcome.

The rehabilitation of English football

Things had been much worse. Euro 96 was a key part of the English game’s rehabilitation into European football after the 1985 Heysel disaster and subsequent half-decade ban on clubs. Prior to Heysel, the FA had bid to host Euro 88, which could have been awkward had the proposal not been easily outvoted by the DFB’s. “West Germany’s presentation was far better than ours,” fair-copped the FA chairman Bert Millichip. “That gave me an insight into what we needed to do.”

What they did was a good old-fashioned handshake deal behind closed doors. England struck an entente cordiale in which they’d step back from trying to host the 1998 World Cup, in return for a Gallic nod for the Euro 96 rights. After England’s chief rivals, the Dutch, helpfully opted to focus on a bid for Euro 2000 instead, Portugal, Austria and Greece were outvoted at a UEFA Executive Committee summit in Lisbon on May 5, 1992. Football was ‘coming home’.

Within six months, the game had changed. Those bids had been for a tournament hosting eight teams at four stadiums, expected to be Wembley, Villa Park, Old Trafford and one of Elland Road, St James’ Park and Roker Park. However, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and fracturing of Eastern Europe meant UEFA’s membership numbers had mushroomed from 35 countries to 49, and with FIFA expanding their own quadrennial jamboree from 24 sides to 32, UEFA’s table-for-eight suddenly didn’t seem like much of a party. Couldn’t squeeze in a few more, could you? Call it a nice round 16 teams in eight venues?

There was talk of involving Cardiff Arms Park (this being pre-Millennium), joint-hosting with Wales, but English stadia were upgrading due to the Taylor Report following the Hillsborough disaster, so the FA had a decent choice. Elland Road and St James’ got the nod, joined by the City Ground, Anfield and Hillsborough itself, as well as Old Trafford, Villa Park and Wembley.

England’s 15 guests secured invites in the usual array of hammerings and heartbreaks. To celebrate UEFA’s first use of three points for a win, Spain racked up 26 from a possible 30. France conceded two goals in 10 games and scored 10 in one, against hapless greenhorns Azerbaijan. At least the new boys finished with a point against Poland – Estonia got none.

It didn’t all go to form. Locked in a three-way battle with the Czech Republic and Norway, Guus Hiddink’s Dutch side required a play-off to qualify. There they took on Jack Charlton’s Republic of Ireland – who had just about held off Northern Ireland – and dismantled them at Anfield, described by FFT as “like watching Liverpool against Rochdale”. Charlton resigned.

At least they came close. Wales, a spot-kick away from reaching the 1994 World Cup, were miles away from qualifying for a crack at the Saesnegs two years on. Under Mike Smith and then the despised Bobby Gould, they finished behind Georgia – getting smashed 5-0 in Tbilisi – and Moldova, although they did somehow conjure up a 1-1 draw in Dusseldorf (spoiler alert: Germany qualified).

Scotland advanced with the second-best defensive record of three goals conceded in 10 matches. Their reward? A dream draw against the Auld Enemy, along with Switzerland and the Netherlands.

As kick-off neared, preparations were far from smooth. Newcastle City Council considered suing the government over a lack of funding; one organiser called it a “frigging nightmare”; another said the FA was “unable to organise a p**s-up in a brewery”.

The FA labelled the government “startlingly short-sighted”. John Williams of the Sir Norman Chester Foundation for Football Research sighed, “It’s a typically botched cock-up at the last minute. Only this country could ever run an event quite like this.”

The Dentist's Chair

In mid-May, Venables announced a 27-man squad, to be cut to a final 22. Mark Wright, the Italia 90 sweeper who missed Euro 92 through injury, suffered a fresh knee ligament strain and never played for England again. Neither did Peter Beardsley, 35. Rob Lee, Dennis Wise, Ugo Ehiogu and Jason Wilcox also made way.

Of the 22 Venables selected, only nine had won more than 10 caps before the finals got going; by way of comparison, that applied to 17 of Bobby Robson’s 20-man Euro 88 squad. A pair of young lads at West Ham were also invited along to train with the England squad at the tournament: Frank Lampard Jr (18) and Rio Ferdinand (17).

First, though, Venables took his provisional squad to Asia. They beat China before playing an unofficial match against something called a Hong Kong Golden Select XI, who played in all-pink and had a 36-year-old Mike Duxbury, as well as the 34-year-old duo of Dave Watson and Carlton Fairweather. England’s tight 1-0 win had the Daily Mail spluttering, “A bunch of has-beens show up a bunch of wannabes”. But worse faux-outrage was soon to follow.

Knowing that Paul Gascoigne was keen to celebrate his 29th birthday a day early, and aware that the players needed to relax ahead of the official naming of his 22-man squad, Venables allowed his men out to a nearby bar – chaperoned by his assistant, Bryan Robson, never one to shy from a sherbert or two. Soon, various players were splayed backwards in the bar’s signature gimmick: a dentist’s chair in which patrons perched to have their gullets engorged with spirits.

"It was Gazza’s birthday, the players had been really good up to that point, and they hadn’t been allowed to have a drink. We finished the game in Hong Kong and Terry gave them permission to go out for a couple of hours and celebrate. It helped the lads bond and come together as a group."

Bryan Robson

“I only went in for a filling!”

Gazza reveals contrition to FFT

With all of the carnage caught on camera, the press enjoyed its usual orgasms of outrage and employed the moralistic doublethink of condemning indiscretions it revels in revealing. This was the era of laddism and Loaded; of the Gallagher brothers filling stadiums and gossip columns; of Men Behaving Badly averaging 13 million viewers, its fifth series of bantering blokes and eye-rolling ‘birds’ beginning during Euro 96. Booze was news. Tutting beckoned.

The Sun led with headline ‘DISGRACEFOOL’, targeting Gascoigne (“Look at Gazza… a drunk oaf with no pride”) then writing off the whole team (“The only thing that we’ll win is the Men Behaving Badly trophy for drunken also-rans”).

Gascoigne, typically ebullient, later told FFT, “I only went in for a filling!” But there was more to it than that. “I was first in the chair because it looked like a laugh,” said Gazza, outlining his default modus operandi. “Then a few of the other lads did it. It was good for team spirit.” No pun intended.

Spirit and bonding are words that recur in accounts from those who were present. Years later, Bryan Robson explained to FFT: “A lot was made of what happened, but it was all blown out of proportion.

"It was Gazza’s birthday, the players had been really good up to that point, and they hadn’t been allowed to have a drink. We finished the game in Hong Kong and Terry gave them permission to go out for a couple of hours and celebrate. It helped the lads bond and come together as a group. They knew they’d trained very hard.”

Paul Ince concurs, saying it was a 'bonding session. We had such a great time'.

And those bonds were needed as the story grew bigger. Embarrassment was exacerbated when the airline bringing the squad back claimed that £5,000 worth of damage had been done to a television and table, which made you wonder where they bought their televisions and tables.

The moral guardians of Fleet Street were outraged on the nation’s behalf. “We pay lip service to drunk, flatulent, screen-smashing yobs by calling them heroes, aware that if they were unable to kick a ball in approximately the right direction they would be up in court,” thundered Daily Mail sportswriter Jeff Powell.

In came another oar from Conservative MP John Carlisle, who raged, “The culprits should be identified, publicly exposed and thrown out of the squad at once. And if that includes Paul Gascoigne, then so be it.”

The players were initially shocked by the reaction; the idea that the popular press could turn the team into pariahs shortly before a big tournament, exaggerating any detail and even – steady yourself – stretching the truth.

“We were surprised by some of the stories off the back of it as they weren’t true,” said wiry-legged winger Steve McManaman, who shared the front page splash with Gascoigne. “Talk about negative press...”

The FA stayed quiet for five days before the players accepted collective responsibility. Forced together by a snarling press, they then adopted the siege mentality preferred by Alex Ferguson at Manchester United. As Shearer said, “Terry used the whole thing in a positive way. ‘The world’s against us,’ he told us. ‘If it’s a fight they want, let’s give ’em a fight.’”

Sheringham, another primary photo figure, thoroughly agreed. “We received so much stick going into the Euros. All we did was make it work for us. Yes, it was a prove ’em wrong approach – but it worked.”

That us-against-them attitude never really left the squad, whether the tabloids were vilifying or deifying them, and it was certainly the first to begin with. Once the players had been deemed targets, the paparazzi followed them everywhere.

Ince tells FFT how, upon the team’s return to English shores under a tabloid hate campaign, Venables afforded the players a couple of days off. Ince went to a pub in Epping. “I met some of my friends and just had a beer or two,” he told FFT in 2020. “Suddenly there were all these paps there, taking pictures of us over a hedge in Epping Forest. The next thing I know, in the News of the World, it was: ‘Do they ever stop drinking?’

“All of the criticism from the dentist’s chair made us stronger and mentally tougher, to prove that we were going to do the business.”

A tournament for all of England

FFT’s preview issue had the sidebar, ‘Who the hell is Zinedine Zidane?’

Few shared this belief. As FFT put it before the tournament, “Only the most fervent optimist thinks England will storm home. No, the big questions for Brits are: will we see some good football? Will there be any violence? And, for those who are really serious about the game’s long-term future, will the Championship create a boom which benefits grassroots football?”

The Dutch were 9-2 favourites despite their qualifying wobble, with Italy and Germany 5-1. England’s 7-1 was likely lowered by bookies minimising risk against the usual weight of patriotic bets. Scotland were out at 50-1; only the Czech Republic (80-1) had longer odds.

Pre-tournament excitement didn’t focus on England’s chances. It was about hosting, and meeting new friends. FFT’s preview issue had the sidebar, ‘Who the hell is Zinedine Zidane?’ The answer, apparently, was “a good example of ‘crazy name, sensible guy’ syndrome”.

Around the country, visitors rocked up at incongruous locations. The Czechs descended on Preston, played a warm-up game against non-league Bamber Bridge and bought Kiss Me Quick hats on Blackpool promenade. Down the road, Russia’s press officer, Lev Zarakhovich, straight-faced his way through the memorable line, “Training has been cancelled – they have the day off and are planning a shopping spree in Wigan.”

The team were ranked third in the world at the time. Meanwhile, Croatia settled into Rutland’s Barnsdale Country Club, where their Vjesnik daily paper waxed lyrical about “the hunting lodge of William II, the oasis of peace, seclusion and idyll”. In Birmingham, the Dutch had a hiccup when Edwin van der Sar misplaced his passport on a school bus.

Not everyone was happy. Settling close to Macclesfield, the Germans were unimpressed by the quality of the surface at nearby Moss Rose, sending Silkmen veteran Steve Burr into passive aggression: “Our ground is certainly not as smooth as Old Trafford, but it’s in good condition. But if Berti Vogts says the ground is bad, then it’s bad. He’s a world champion and we’re only semi-professionals.”

Also unimpressed were the Bulgarians. With fixtures in Leeds, then Newcastle, they chose to split the difference and pitched up outside Scarborough. Those who had seen the bright lights of USA 94 and Barcelona were strangely unmoved by the charms of Yorkshire’s seaside. “Scarborough is boring,” decreed striker Hristo Stoichkov, as the squad decamped early and moved to Stockton-on-Tees instead.

Clearly, not everything about the 1996 UEFA European Championship would go to script...

This feature first appeared in the February 2020 issue of FourFourTwo - get the latest issue now.

This is part one of this feature: Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

More England features

Before Three Lions: How Baddiel and Skinner’s Fantasy Football defined football in the 1990s

Gazza, the untold stories: Need-to-know tales that launched a legend

The inside story of ‘An Impossible Job’, the 1994 Graham Taylor England documentary

Gary Parkinson is a freelance writer, editor, trainer, muso, singer, actor and coach. He spent 14 years at FourFourTwo as the Global Digital Editor and continues to regularly contribute to the magazine and website, including major features on Euro 96, Subbuteo, Robert Maxwell and the inside story of Liverpool's 1990 title win. He is also a Bolton Wanderers fan.