Why was the European Super League's launch so bad?

The Super League lasted just two days before Premier League sides pulled out and killed the idea. How did the world's biggest clubs oversee such a shambles?

A European Super League is still seen as a threat to football

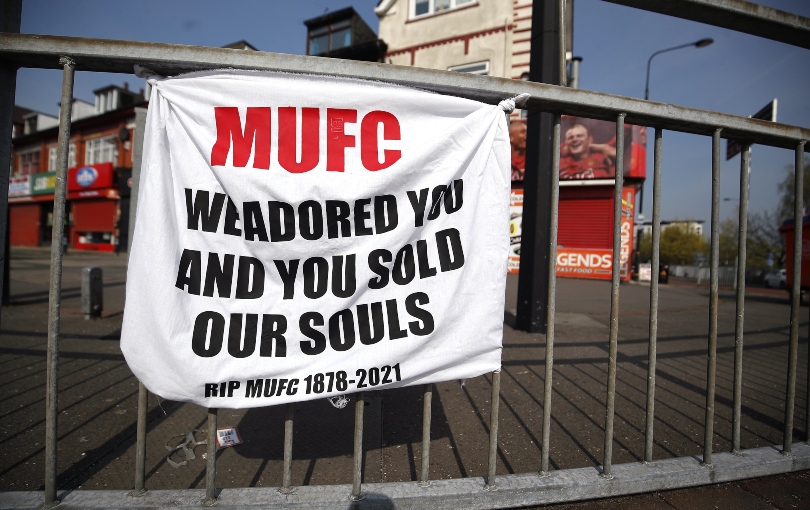

(Image credit: PA)Barely two days have passed since the announcement of the European Super League, and the project is already in tatters.

Founding members are fleeing – but that may well be the least of the problems for these 12 clubs' owners.

Players spoke out against it. Managers spoke out against it. Fan opposition groups formed. The British government announced a review into football governance.

Catching people by surprise should have made it easier to push this through; you can't try it twice.

If they don't pull it off now, the prospect of a future Super League is laughable, and UEFA and FIFA have been hardened against offering 'elite' clubs concessions in future negotiations around their own competitions. After all, what are they going to do? Make their own league?

All of the Premier League clubs have pulled out, but the consequences are only beginning. One of the architects of the deal, Manchester United executive vice-chairman Ed Woodward, has announced his resignation. It could barely have gone worse.

“They’re bottle merchants... in a few weeks they’ll say it was nothing to do with them.” Worth revisiting what @GNev2 said on Sunday 👏 pic.twitter.com/KI4sWof77PApril 20, 2021

The 48 hours or so between rumours first appearing on Sunday afternoon to Chelsea pulling out on Tuesday evening was a perfect example in how not to launch a controversial project.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And it's hard to understand why it went so badly. Yes, it's an appalling idea and yes, it was done for the wrong reasons – but it's not hard to see how it could have gone better.

After all, these are 12 of the biggest clubs in the world, with both eyewateringly rich financial backers, and enormous and fanatical fanbases. In some cases, they've managed to cultivate online armies in support of dodgy governments on the other side of the world. Can they really not sell the idea of Liverpool playing Barcelona twice a year?

Here's seven questions about the shambolic launch:

Why did they launch in the middle of the night in Europe?

The announcement was expected at 9.30pm UK time, but didn't come through until around 11.30 – past midnight in Italy and Spain.

After a day of rumours, fans wanted clarity. What this did was immediately set a tone for supporters in these clubs' home countries: this isn't about you, and it doesn't matter if you miss the biggest news in your team's history.

What was the story?

Essentially: why did they launch the Super League? Obviously, we know the real reason: these clubs thought they could get more out of Champions League reforms, and when that wasn't forthcoming, came to the conclusion that the biggest money-spinner was a breakaway.

But there was no rival narrative to this, no big moment that felt like a trigger. There were some half-hearted noises about COVID, but all that really prompted was questions about why, after a season in which many of these club's managers had complained about a congested schedule, they were signing up for more games?

With a lack of information, people were left to make their own assumptions, unchallenged.

How was this going to help smaller clubs?

The launch claimed "solidarity payments in excess of €10 billion" to support European football to fund a new model of financial sustainability.

This could have been a surprising ace in the pack for making the Super League's argument: yes, this is all about money, but football is in a crisis deepened by the pandemic, and we have a solution that will prevent future casualties like Bury. You may not think it's perfect, but the current system isn't working.

Then explain how that will work, and how much extra money smaller clubs might expect to receive.

Which brings us to...

Why wasn't there criticism of football's problems?

As mad as it seems, the Glazers, Agnellis, Perezes and Henrys of this world are not usually football's biggest problems.

FIFA is hardly the most-loved institution. Arrests and corruption scandals abound. UEFA had already given away the principled opposition to a Super League by ringfencing positions in the Champions League based on historical achievement.

It's not hard to make an argument that these organisations are stuck in the past, too slow to make decisions, and beholden to money. What we got was a project that was so palpably greedy and inept, it made FIFA and UEFA look good by comparison.

And at a time when people are fed up with all sorts of aspects of the game – from split TV rights, to VAR, to ticket prices – there was no sense that the aim was to fix any of football's problems.

Where were the faces?

Who spoke up in favour of this project? In the UK, Manchester United co-chairman Joel Glazer gave a single quote as part of the press release announcing the Super League, saying that it would open a "new chapter" for football.

In Spain, Real Madrid president Florentino Perez gave a late-night interview in which he claimed the project would "save football".

Other than that, nothing.

These clubs are not amateurs when it comes to communications; they keep in contact with club legends – particularly those who have media careers. Could they really not find anyone who backed the idea? Did they try?

What we got instead was the usual mouthpieces for these clubs – the players and managers – increasingly showing their unhappiness with the idea in their own mandated interviews. Not a single public persona made the case in favour in the British media.

Why weren't players and managers told?

Of course, you want to avoid leaks. But the news was already out by mid-afternoon on Sunday. The players and managers are the ones who face the media, who de facto become the spokespeople for this decision, weren't told about it until afterwards – and that lack of consultation became a major catalyst in the whole thing falling apart.

Why didn't they tell the national governments?

Again, the obvious rebuttal to this is that it was an incredibly sensitive business decision that you would want to announce on your own terms.

But, er, given they didn't do that anyway, it probably would have been a good idea to let the UK government know that you had a plan to blow up one of the country's most iconic and lucrative exports.

Given there were six English teams involved, a case based on helping the post-COVID UK economy, supporting lower-league teams and showing a post-Brexit Britain open to both Europe and the wider world should have been music to this government's ears. Instead, they were promised a "legislative bomb" to block it.

It's not like they didn't have the contacts: the PR company for the Super League is run by two people who worked for Boris Johnson.

Instead, they have handed the government the political will to push through changes to the way football clubs are run – potentially taking power away from those who made these decisions, and preventing them from doing anything like it again.

At every level, this has been a complete failure, and it's no less than they deserve.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get your first five issues for just £5 for a limited time only - all the features, exclusive interviews, long reads and quizzes - for a cheaper price!

NOW READ

ANALYSIS Is the European Super League just a bluff to get more out of the Champions League?

PUNISHMENT Gary Neville wants English clubs joining European Super League to be relegated

SLATED Former players, fan groups, celebrities and MPs slate European Super League idea

Conor Pope is the former Online Editor of FourFourTwo, overseeing all digital content. He plays football regularly, and has a large, discerning and ever-growing collection of football shirts from around the world.

He supports Blackburn Rovers and holds a season ticket with south London non-league side Dulwich Hamlet. His main football passions include Tugay, the San Siro and only using a winter ball when it snows.