Everton's long wait for silverware is far from unique as football's superpowers continue to dominate

Everton last lifted a trophy in 1995, yet they are just one of many clubs starved of success

Neville Southall turns 63 in September. Everton’s greatest goalkeeper may be referenced still more often than usual this weekend. Coupled with Paul Rideout’s earlier goal, it was Southall’s brilliant double save from Paul Scholes that won the 1995 FA Cup. Dave Watson, who turns 60 in November, lifted it.

Perhaps, had Southall known it would be Everton’s last silverware for a quarter of a century, he would have attended the post-match celebrations. Perhaps, as the contrarian he is, he would have driven home to Wales anyway.

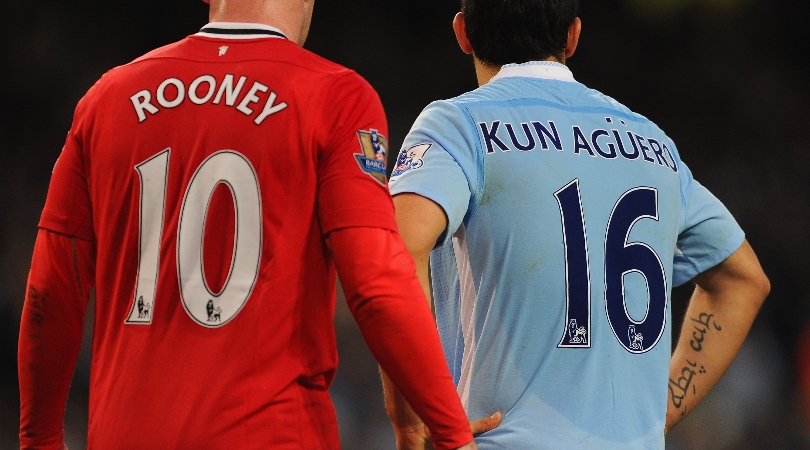

Whichever, Everton face Manchester City on Saturday in the FA Cup in a familiar position. Barring an upset, another year will slip away and the longest trophy drought in their history could get longer.

An Evertonian lament of their wait would feature the 2009 FA Cup final, which they led after 25 seconds, and a 2003 defeat to a Shrewsbury side managed by their most successful captain, Kevin Ratcliffe, but who were relegated from the Football League later that season.

Theirs is both an idiosyncratic tale and a familiar one. Aston Villa’s last trophy came in 1996, in the League Cup. Wolves’ most recent major silverware was in 1980, as was West Ham’s. Leeds have no silverware since the 1992 league title, Sheffield Wednesday none since the 1991 League Cup. Steve Bruce, 60, must be one of the younger Newcastle fans who can actually remember them claiming the 1969 Fairs Cup. Their neighbours Sunderland at least won a trophy this year: the Football League Trophy. Wolves, Stoke, Bolton, Coventry and Southampton are among the other bigger clubs who took the cunning approach of dropping into the lower two divisions to boost their chances of silverware.

At various points, some have been among English football’s aristocrats, at others they have ranked among the mid-ranking members of the top flight. In previous years, they might have been Cup teams; now there aren’t any. The superpowers can win them even then their attention is often diverted elsewhere. Since the start of the 2013/14 season, 21 major English trophies have been decided: between them, Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City and Manchester United have won 20, plus two Uefa Cups and one Champions League. Only Leicester’s 5000-1 shot in the 2015/16 Premier League denied them a clean sweep.

Everton, Villa, Newcastle and their ilk can rue the fact that unfancied outsiders like Wigan, Swansea and Birmingham have won the knockout competitions more often. Those were missed opportunities, but were others, when clubs with far greater resources, bigger squads, better players and, often, superior managers prevailed? Because in the last 20 seasons, the same five clubs have won 19 Premier Leagues, 18 FA Cups and 15 League Cups: that is 52 of a possible 60 (plus four Uefa Cups and four Champions Leagues). Even then, a 53rd, the 2008 League Cup, was Tottenham’s lone trophy of the millennium. The last member of the big six, often the one with the smallest budget, stand alone, neither fully in one group or the other.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Their past offers a reminder of how football has changed; they were FA Cup winners in 1981 and 1991, despite or because they finished 10th each season, Uefa Cup winners in 1973, when they came eighth, and League Cup winners in 1999, when they were 11th. In most cases, that amounted to underachievement in the old Division 1 or the Premier League; these days, the quest to prevent that leads to the sort of weakened teams that can produce the kind of tame Cup exit that Wolves accepted this season.

As it transpired, victory over Southampton would have earned them a very winnable quarter-final versus Bournemouth. Maybe the pragmatist in Nuno Espirito Santo would rationalise that even then, a semi-final or final against Chelsea or a Manchester club would come with the probability of defeat. Perhaps he recalled that Watford, Wolves’ conquerors in the 2019 semi-final, duly lost 6-0 to City in the final. Maybe Wigan’s double of the 2013 FA Cup win and relegation make them a salutary warning.

And certainly the size and history of England’s eternally frustrated clubs confers no divine right to silverware. Yet, and while this may be a lament for a bygone era of greater unpredictability and a more equitable distribution of glory rather than a constructive suggestion of how to change anything, it is a shame when so many fine clubs and silverware-starved fanbases spend decades being denied the release of joy it brings, and not merely because it would mean more to them than to most of the actual winners. The gulf that has grown between the best and the rest feels too big, the shocks are largely confined to the earlier rounds and the usual suspects invariably triumph. And before long Neville Southall will probably collect his pension while remaining part of the last Everton team to win a trophy.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and save up to 58% - get a quarterly FFT sub for only £12.25.

NOW READ

CHELSEA Who does Chelsea's loan system work for? How Patrick Bamford left for better things

CHRIS FLANAGAN Son Heung-min's incredible journey to the top: how the Tottenham star made it

Richard Jolly also writes for the National, the Guardian, the Observer, the Straits Times, the Independent, Sporting Life, Football 365 and the Blizzard. He has written for the FourFourTwo website since 2018 and for the magazine in the 1990s and the 2020s, but not in between. He has covered 1500+ games and remembers a disturbing number of the 0-0 draws.