The man who stole the FA Cup – how a kleptomaniac pensioner ended the 63-year mystery

The baffling theft of the original FA Cup went unsolved for over six decades. Then came a confession...

This feature originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe today and save 37%: all the exclusive interviews, long reads, quizzes and more but with more than a third-off normal price.

It was just past midnight on the morning of Thursday September 12, 1895, and rumbles of thunder disturbed the skies above Birmingham. Three men stood in darkness on the flat roof of a boot and shoe shop in New Town Row, to the north of the city centre.

They stripped back the zinc cladding from the roof before smashing a hole through the ceiling. Then, two of the men slowly lowered the other into the deserted shop. Inside, the thief opened the till and pilfered small change amounting to two or three shillings. His real target was elsewhere, sitting behind a sliding partition in the shop window.

There, mounted on a stand and surrounded by football boots, was a shiny silver trophy – around 16 inches tall with handles, a lid and tiny bearded figure with a ball at his feet. But this wasn’t just any old trophy: this was the original Football Association Challenge Cup.

The miscreant grabbed it, carried it up onto the roof and away into the night, never to be seen again. It would be more than 60 years before the mystery of what happened to the original FA Cup was solved. Sort of...

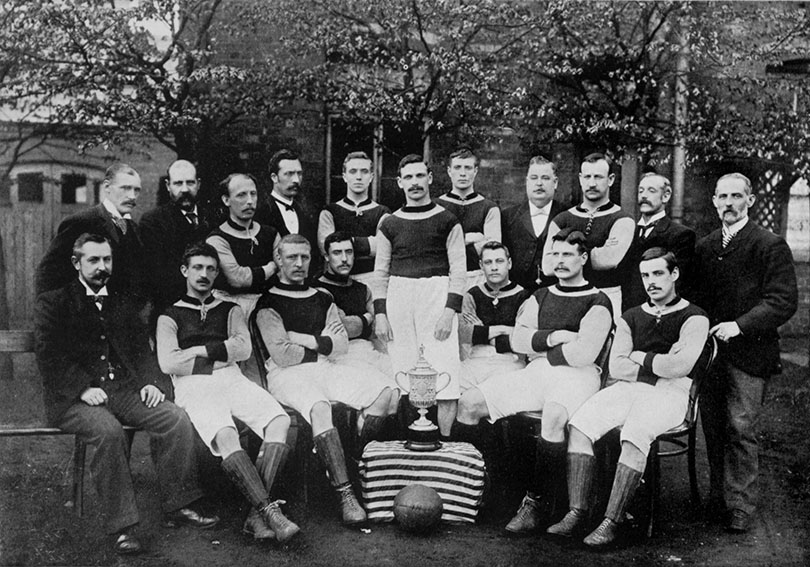

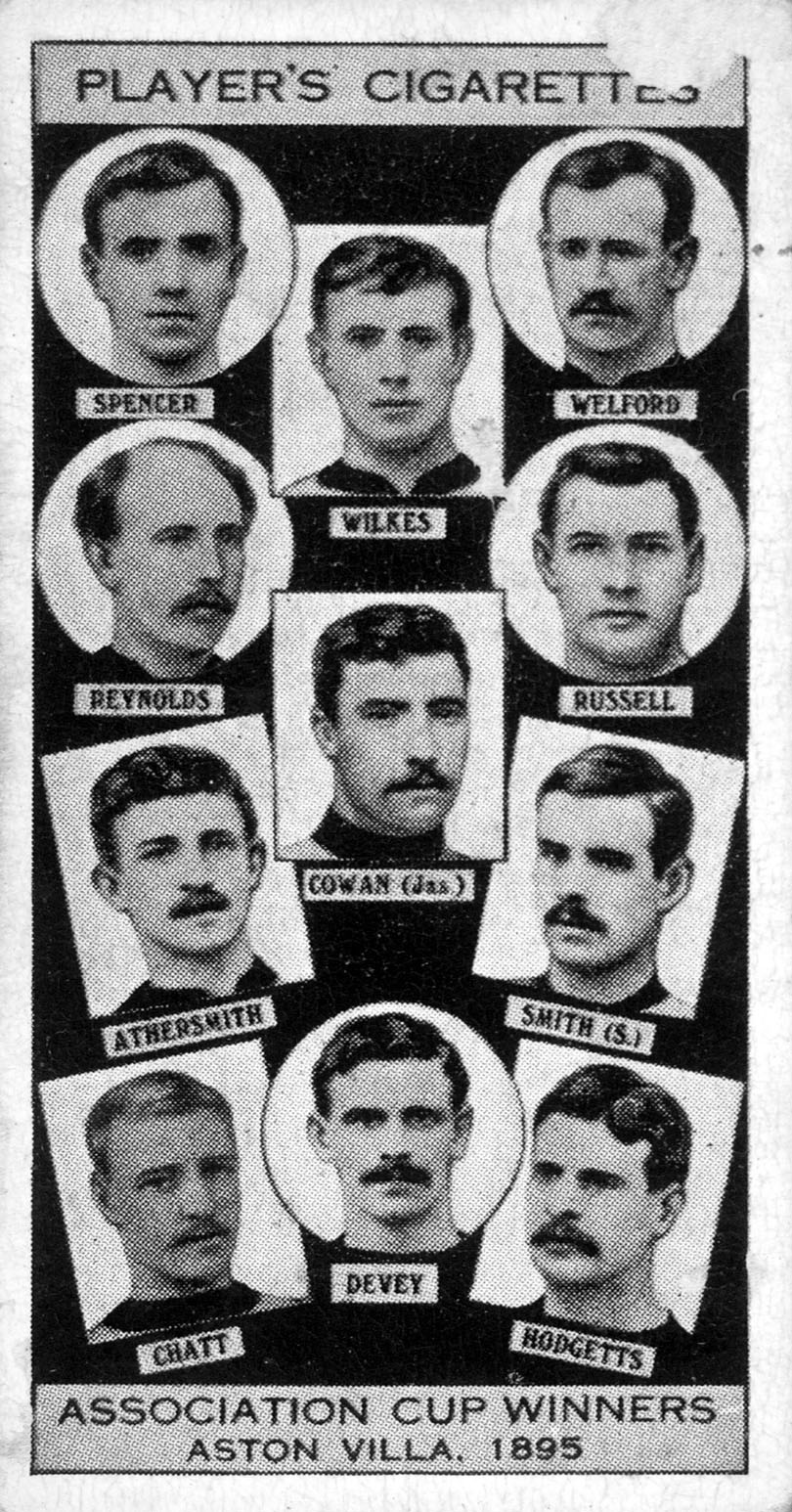

Aston Villa had lifted the trophy five months earlier, against Midland rivals West Brom at Crystal Palace. The 24th FA Cup final was settled by a single goal scored after only 30 seconds, when a shot from inside forward Bob Chatt was deflected into the net by Villa skipper Jack Devey.

Villa may have been defending First Division champions in the 1894-95 campaign, but the FA Cup was football’s biggest prize. They took it back to Birmingham and were met at the train station by a huge crowd of supporters, who cheered as captain Devey proudly held the trophy aloft. At a club reception, the cup was filled with champagne and toasts were made to the team and officials. Afterwards, the cup was stored inside Villa’s safe at their Perry Barr ground. It wouldn’t remain safe for very long.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

William Shillcock was a local boot and shoe manufacturer, who supplied football boots to the victorious Villa side “and 16 international players”. He also sold jerseys, knickerbockers and eight different types of balls, including a “best cowhide” version used by Villa as well as the senior England team. The 73-year-old was considered a first-rate Villa supporter, so when he asked for permission to exhibit the FA Cup in the display window of his shop, the club’s committee agreed.

Shillcock’s football works factory was based in a converted row of terraced houses, with his shop in a single-storey extension erected over the front yards. Its big plate glass display windows were packed with footwear, sports equipment and other trophies – several of which, it was noted, had higher intrinsic value than the FA Cup.

This, however, was a trophy worth far more than its pawn shop price.

The competition had been established in 1871 by FA secretary CW Alcock. The FA had struggled to establish itself outside London, and it was thought that a national knockout tournament could solidify the organisation as football’s leading authority. A modest trophy was commissioned at the cost of £20 (about £1,900 today) from the Sheffield silversmiths Martin, Hall & Co, and 15 teams entered. The final was won by Wanderers – captained by Alcock, obviously – who beat Royal Engineers 1-0 at Kennington Oval.

According to the authoritative early tome Association Football & the Men Who Made It, the competition proved an “epoch-making” event of “vast importance”. Dubbed the ‘little tin idol’, the trophy represented the glamour and sentiment of football and was also “the inspiration for the Association game”.

The little tin idol was popped in Shillcock’s window near the end of August, and for two weeks drew large crowds of viewers and no doubt a decent amount of extra trade.

On the evening of the robbery, the elderly Shillcock locked his shop as usual at around 9.15pm. When he returned at 8am the next morning, he soon saw the till’s cash drawer lying empty on the counter. There was some broken plaster on the floor and a small hole in the roof, but the shop’s two safes and other valuables were untouched. Shillcock thought it was a curious burglary – until he checked the display window and discovered that the FA Cup was gone.

Detectives Brown and Davis of Birmingham City Police inspected the crime scene. Entry was clearly gained through the roof, and the detectives assumed the thieves had climbed the shop’s 12ft exterior wall, which they both admitted was “no easy task” and could only have been achieved by someone young and fit. On the roof, the detectives found an old chisel and putty knife, which had been used to strip away the zinc and create a hole about 12 inches wide. Wooden beams and plaster ceiling had then been kicked through using stamped boots. The tight size of the hole and presence of small boot prints confirmed the detective’s suspicions that the thieves were “slightly developed” youths.

Shillcock’s shop was insured, but this didn’t cover the cup beyond its natural value. The beleaguered owner distributed handbills (left) across Birmingham offering a £10 reward (worth around £1,200 today) for its recovery. As holders of the trophy, though, Aston Villa were ultimately responsible for its safety and had agreed a guarantee with the FA to the value of £200, payable in the event of its loss. “Aston Villa will, I am sure, make every effort to discover and regain possession of the cup,” snarled the FA’s secretary, Frederick Joseph Wall, in a statement. “I am sanguine that it will be recovered.”

Such optimism was sadly misplaced.

Sixty-three years later, in February 1958, an 80-year-old resident of an old people’s home made an “astonishing confession”.

“I STOLE THE FA CUP,” yelled the headline on the cover of the Sunday Pictorial, soon to be renamed the Sunday Mirror. Harry Burge, a teenager in 1895, and two now deceased companions had committed the crime. Burge went back to Shillcock’s – by then a grocery shop – along with a Pictorial photographer and explained how he had broken in. Rather than making the difficult climb up the shop’s exterior wall as originally believed, however, the thieves had simply accessed the roof via the empty works building.

“It was just turned midnight when the three of us forced a lock on the door at the back of the building with a jemmy,” recalled Burge. “Once inside, we were able to climb through an upstairs window onto the flat roof – open to the street – over the shop’s front windows.”

The thieves smashed through the roof and snatched the trophy. “Then we all went back to my home in Hospital Street, a few minutes’ walk away. That night, we broke up the cup before melting it down inside an iron pot. My pals had several moulds for making a ‘snide’ of half-crowns, so we used the silver to turn out a number of these coins.”

Burge & Co proceeded to pass these fake half-crowns (worth two shillings and sixpence or about £15 each now) in a Birmingham pub called the Salutation, which was owned by legendary Villa forward Dennis Hodgetts and frequented by many of his Lions team-mates. “Villa players often used it,” smirked Burge, “and some of them may have handled the dud coins not knowing the silver came from the stolen cup.”

Birmingham police initially said they might reopen the case and consider charging Burge, but the records they held of the burglary were “slender” and no action was taken.

The confession meant catharsis for Burge. “I’m an old man now, and I want to get the thing off my mind,” he said. “It has troubled my conscience for a long time.”

Henry James Burge was a career criminal, who had 42 past convictions dating back to 1897 and had spent 46 years and 11 months behind bars. Reports covering his misdeeds refer to him as a “chronic thief” and “danger to the community”. Even in May 1958, three months after his FA Cup admission, he was charged with snatching three coats from an unattended van. Burge’s solicitor requested leniency, as he was an old man in ill health and didn’t want to die in prison – but the magistrate was familiar with his many indiscretions.

“I told you that if you did this sort of thing again instead of retiring from a life of crime, I’d send you to prison for a long time,” he finger-wagged.

Burge was sentenced to seven years, serving just over two and a half. He had spent almost half a century at Her Majesty’s pleasure, and passed away at Summerfield Hospital in 1964.

The story didn’t die with him, though. Eleven years later, a man named Edwin Tranter told the Birmingham Evening Mail that his grandfather, Joseph Piecewright, had pinched the FA Cup. While the claim couldn’t be proved, Piecewright may well have been one of Burge’s two associates. Another two decades after that, an elderly woman named Violet Stait suggested her father-in-law, John ‘Stosher’ Stait, had also nicked the trophy from Shillcock’s window. Stosher could have been another accessory, albeit Violet’s story had him walking straight out the front door with the cup, which didn’t match the evidence.

Back in autumn 1895, the new season’s competition kicked off, according to Sporting Life, as a “struggle for a cup not in existence”. By February 1896, with the semi-finals fast approaching, it was accepted that the trophy was gone and a replacement was needed. Initially, the FA proposed that the substitute should be a grand gold trophy worth up to £250 (£30,000 today), but RP Gregson of the Lancashire FA successfully argued that the replacement should be “as nearly as possible like the old one”, because what was crucial was “not so much the value of the trophy as the honour of winning”.

Luckily, after Wolves had claimed the cup in 1893, their president ordered replicas for the team and a silversmith made mouldings from the first trophy. The new one – created by Birmingham business Vaughtons, where former Villa and England forward Howard Vaughton was a partner – was an exact copy of the lost prize bar a couple of minor details. The trophy was formed using 100 ounces of silver instead of 40, while the small figure on top was altered from a bearded ‘Methuselah’ to a youthful athlete. The second version was even sat on the original ebony stand, which had been left behind by the thieves.

The Wednesday defeated Wolves 2-1 to lift the replacement tin idol in 1896, followed by Double-winning Villa a year later, Nottingham Forest and Sheffield United. After Newcastle won it in 1910, the trophy was retired and presented to FA president (and five-time FA Cup winner) Arthur Kinnaird, partly because the design was not copyrighted and unofficial duplicates were being produced and sold.

A new, larger FA Cup in the current design was produced by Fattorini & Sons of Bradford – just in time for Bradford to win it in 1911 – with two copies subsequently generated due to wear and tear. The replacement tin idol – the oldest surviving FA Cup – was auctioned by Bonhams in September 2020 for £760,000.

Apparently, you can put a price on history.

While you're here, subscribe to FourFourTwo today and save 37%. All the exclusive interviews, long reads, quizzes and more but with more than a third-off normal price.

NOW READ

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world