Famous bosses' not-so-famous brothers: Shankly, Fergie and more

Shanks, Chapman, Hiddink and Ferguson are names synonymous with glory – but what of their unheralded siblings’ forays into management? FFT digs out the family album...

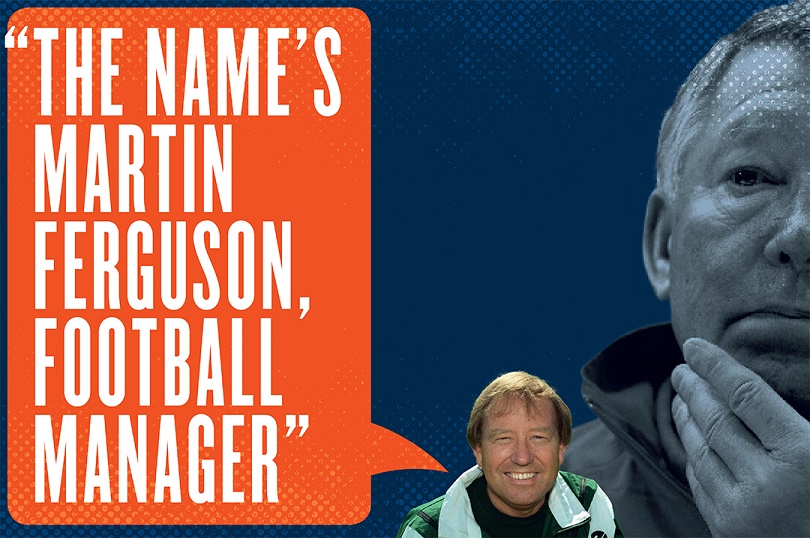

Martin Ferguson

Managed: Waterford United, East Stirlingshire, Albion Rovers

Words: Chris Flanagan

Martin Ferguson’s philosophy was clear. “My ideas about football are a bit like Alex’s,” he once explained. “We are totally opposed to negative play. There was only once or twice last season that I asked my men to play defensively. On one of those occasions we lost 6-0.”

The year was 1982 and Martin was in charge of East Stirlingshire, just as older brother Alex had been eight years earlier. For Alex, it was a springboard on to bigger things. The future knight of the realm was in charge of the Scottish minnows for just 117 days, but that was long enough to impose his will and hunger for success. Forward Bobby McCulley called him as “a frightening bastard from the start” and a run of wins – including a first league victory over their neighbours Falkirk for 70 years – quickly earned Alex a job offer from St Mirren.

For Martin, things didn’t go quite so well. East Stirlingshire was his second job in the dugout. The former Partick, Barnsley and Doncaster inside-forward, who began his playing career at the scintillatingly named Kirkintilloch Rob Roy, had first moved into management as player-boss of Irish club Waterford in 1967. He was only 25 years old, but Rovers boss Keith Kettleborough had spotted his managerial potential and recommended Ferguson for the job.

Martin worked as a coach at Albion Rovers before getting the East Stirlingshire job not long after Alex had won his first Scottish league title with Aberdeen

Ferguson helped Waterford to the league title and the final of the FAI Cup. He left just before that final after a disagreement with the club chairman, only a year into the job, and could only watch on from Scotland as Waterford faced Manchester United in the European Cup months later.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

It would be 13 years before he’d manage again. Martin worked as a coach at Albion Rovers before getting the East Stirlingshire job, not long after Alex had won his first Scottish league title with Aberdeen.

“I took on the job at East Stirling only after a chat with Alex,” Martin said. “He told me the board wouldn’t interfere; that they were not hirers and firers.”

Martin combined the role with a full-time job selling welding rods. There was little glamour at that level of Scottish football. Finances were tight. “At this level it’s a shoestring existence,” he said. “Every penny is a prisoner.”

Facing injury problems, Martin couldn’t prevent East Stirlingshire from dropping out of the second tier in his first season, a level to which they have never returned. He responded with the same ruthless streak his older brother deployed at will. “I was disappointed with the attitude of some of my players last season,” he said after East Stirlingshire’s relegation. “What annoyed me was that some of them felt they were better than they were, so I got rid of so-called stars. I freed seven.”

He did enjoy success as a coach, helping St Mirren and Hibernian into Europe before moving to Manchester United in 1997 to work for Alex as chief European scout

Asked if he had ambitions to follow his brother up the ladder, there were mixed signals. “I’m in this as a hobby and not for the money,” Martin said. “If I weren’t at East Stirling I would be somewhere else. Full-time? I would like the chance to try it, but it’s a big upheaval for your family.

“I look at my brother Alex’s commitment to the game, which is total, and know that it would have to be the same for me. But you must be working for the right club.”

East Stirlingshire started badly in the third tier and Martin departed, taking over as boss of Albion Rovers. He lasted less than a year, with limited success, just as Alex was masterminding Aberdeen’s European Cup Winners’ Cup triumph over Real Madrid. Martin never managed again.

He did, though, enjoy success as a coach, helping St Mirren and Hibernian into Europe before moving to Manchester United in 1997 to work for Alex as chief European scout. He helped bring in the likes of Ruud van Nistelrooy and Jaap Stam (as well as Liam Miller and Kleberson) before calling time on his career in 2013 – only to be then caught out by Alex’s surprise retirement at the end of that same season.

“I told him I knew what he was up to, trying to steal my thunder ahead of my retirement,” he said, tongue firmly in cheek. “I had all the press and television lined up for me making my own announcement, but now he’s gone and spoiled it...”

It perhaps summed up his career in the game: overshadowed by his older brother until the very end. But few acts have ever been tougher to follow.

Next: More interesting international experience than his big bro

René Hiddink

Managed: AD’69, Sint Joris, VVG’25

Words: Arthur Renard

In addition to his time at amateur outfits, René also worked as a coach at sometime Eredivisie yo-yo club De Graafschap and as assistant manager in the Eerste Divisie with Dordrecht

Like older brother Guus, René Hiddink always seemed destined for the dugout – although the early stages of his coaching career were spent at amateur level rather than at the very top. He managed tiny Dutch sides AD’69, Sint Joris and VVG’25 – unlike Guus, who earned global recognition after leading the Netherlands and South Korea to the semi-finals of the 1998 and 2002 World Cups.

Perhaps René wasn’t as ambitious as Guus, who has also managed European giants Real Madrid, Valencia, PSV and Chelsea (twice). In addition to his time at amateur outfits, René also worked as a coach at sometime-Eredivisie yo-yo club De Graafschap and as assistant manager in the Eerste Divisie with Dordrecht. The latter role even involved duties as a scout and opposition analyst.

Working on a part-time basis, he still had time to help out with the family business, Hiddink Sport Management. “We recently recorded a commercial for a large pizza chain in South Korea,” René proudly boasted in a 2006 interview.

When René left Dordrecht in 2011, he was offered a coaching role in Rwanda by Armée Patriotique Rwandaise FC, an army club based in Kigali. “I spoke with Guus and he advised me to do it,” René explained. “It was a great year. We had a really good team and conquered both the league title and the cup.”

Despite his success working at APR, Hiddink occasionally had to report to the barracks. “If you lost a game, you had to report to the generals,” he revealed. “They would ask for an explanation, as they expected you to win every match. We would then say: ‘Don’t worry, General’. Fortunately, we didn’t lose often.”

He later worked as a youth coach at Red Bull Ghana, and as head of the youth academy at Saint George FC in the Ethiopian first division. He didn’t last very long in either post, but at least René has the sort of international experience to which his brother has become accustomed.

Next: They faced each other in a Sheffield derby

Harry Chapman

Managed: Hull City

Words: Paul Brown

Harry Chapman was a better footballer than older brother Herbert. Had his career not been cut tragically short, he may have become a better manager, too.

Harry’s playing career began to outshine Herbert’s, to the extent that Herbert was routinely referred to in press reports as “the brother of Harry Chapman, the Sheffield Wednesday player”

Born in 1879 in the colliery village of Kiveton Park near Rotherham, Harry worked in the mine while Herbert was an office clerk. Both played for Kiveton Park and were two of 11 siblings, with his brothers Tom and Matt also footballers.

Harry signed for Sheffield Wednesday, while Herbert joined Northampton before moving to Sheffield United. The brothers first faced each other in a Sheffield derby on Herbert’s Blades debut, in September 1902, with Harry’s Wednesday winning 3-2. The following month, they played alongside each other for a Sheffield team in an exhibition match against Glasgow, before Harry’s playing career began to outshine Herbert’s – to the extent that Herbert was routinely referred to in press reports as “the brother of Harry Chapman, the Sheffield Wednesday player”.

In 1902/03 Harry scored 12 goals to help fire Wednesday to their first league title, and netted another 17 as they won it again in 1903/04. He went on to register 99 goals in 298 appearances for Wednesday, and was “a popular and clever player” according to the Sheffield Telegraph and, added the Sheffield Independent, “a hard worker and well-respected”. His career highlight was the 1907 FA Cup Final, during which he showed “outstanding brilliance” as Wednesday beat holders Everton 2-1.

A few days after Harry won the cup, Herbert took a post as player-manager of Northampton (“He is the brother of the popular Sheffield Wednesday player,” newspapers helpfully explained). Harry continued to play for Wednesday until 1911, when he moved to Second Division Hull City. At 32, and regarded as having “a thorough knowledge of the game”, he was brought in to help pass on his experience to Hull’s youngsters.

The brothers’ teams met three times during the season: Harry’s Hull won both league games, as well as knocking Herbert’s Leeds out of the West Riding Cup

Unfortunately, during the first match of his second season in September 1912, Harry shattered a kneecap and was carried to the infirmary “calmly smoking a cigarette en route”. Harry had studied anatomy, and knew his playing career was over. Without him, Hull slumped towards the bottom of the table. Things looked bleak, but in March 1913, Harry stepped in as manager. According to the Yorkshire Post: “The old footballer revealed considerable aptitude for his new duties” as he steered the Tigers to a mid-table finish.

Ahead of the 1913/14 campaign, Harry spoke of leading Hull to promotion. Also thinking of stepping up was Herbert, now manager at Leeds City. The brothers’ teams met three times during the season: Harry’s Hull won both league games, as well as knocking Herbert’s Leeds out of the West Riding Cup. “[Hull’s] tactics were either putting the Leeds men off their game, or exposing inherent weaknesses in their play,” noted the Post. Hull’s style of play was considered much more effective than the “slow and closer passing game” attempted by Herbert’s Leeds. Could Harry have been as tactically astute as his more famous brother, or perhaps even more so? Football never got the chance to find out.

In July 1914, Harry became seriously ill and, after a single full season as a manager, he was forced to resign and confined to a sanatorium, suffering from then-incurable tuberculosis.

After two years, during which his wife Miranda passed away, the ailing Harry went to stay with Herbert in Leeds. He died at Herbert’s home in April 1916, aged 36. He left three sons, the oldest of whom, Harry Jr, would later follow his father and uncle into football management with a spell at Shrewsbury Town.

While Harry is largely forgotten, Herbert is remembered as a great moderniser. He revolutionised football tactics and training, and championed innovations such as floodlights and shirt numbers. He won two league titles and the FA Cup with Huddersfield, then repeated the feat with Arsenal. But after nine years at Highbury, Herbert would also succumb to illness. “The brother of Harry Chapman” died from pneumonia in January 1934, aged 55.

Next: The Shankly trailblazer

Bob Shankly

Managed: Falkirk, Third Lanark, Dundee, Hibernian, Stirling Albion

Words: David Craik

For many Dundonians, the name Shankly will always be synonymous with Bob

Mention the name Shankly to supporters around the globe and thoughts will turn to the man who led Liverpool to success in the ’60s and early ’70s, outstretched arms saluting the Kop and his iconic “life and death” comment. In the city of Dundee, though, it’s a very different story.

For many Dundonians, the name Shankly will always be synonymous with Bob – Bill’s older brother by three years, and the man who guided Dundee to their first and only Scottish Football League title in 1961/62.

The following season, he took the Dee to the European Cup semi-finals, two years before Bill’s Liverpool reached the same stage of the competition.

Bob was revered by Jock Stein, Celtic’s European Cup-winning manager, and according to former St Mirren and Aberdeen boss Alex Smith - who worked with Shankly at Stirling Albion, where he was general manager and on the board after retiring from management - Bob was also a managerial mentor to Bill. “They talked on the phone every week about football,” Smith tells FFT, “and Liverpool’s playing style was very similar to Bob’s short passing philosophy. If he had managed in England, he would have done what Sir Matt Busby did. He was that good.”

“Bill Shankly applied for the managerial role at Dundee, but his letter arrived the day after Bob had already been given the job.”

Bob and Bill’s playing and early managerial careers were both spent just below the highest level. Bill played for Carlisle United and Preston North End, while Bob turned out for Alloa and Falkirk. Bill’s management career started in 1949 at Carlisle, before he moved to Grimsby, Workington and Huddersfield Town, where he took the helm in 1956; Bob, meanwhile, was Falkirk manager from 1950 until 1957, leaving just before the team he built won the Scottish Cup. Similarly, Third Lanark reached the 1959 Scottish League Cup Final the year Shankly departed. It would prove to be a pivotal year for both brothers.

“Bill Shankly applied for the managerial role at Dundee,” says club historian Kenny Ross, “but his letter arrived the day after Bob had already been given the job.”

Later that year, Bill became manager of then-struggling Liverpool, winning Division Two in 1961/62 and Division One in 1963/64. The rest, as they say, is history.

Bob enjoyed early success of his own, winning that first championship for Dundee and almost becoming the first ever man to lead a British team to European Cup glory, dumping out Cologne (via an 8-1 first-leg win), Sporting and Anderlecht before losing to Milan in the 1963 semi-finals. The late Scottish football writer Bob Crampsey once said: “They were the best Scottish footballing side since the war – better even than the Lisbon Lions.”

In 1964 Dundee reached the Scottish Cup final, where they lost to Rangers. They could, however, celebrate a season that brought 100 goals across three domestic competitions, which proved to be Dundee’s zenith under Shankly. In February 1965, he replaced his friend Jock Stein at Hibernian.

Highlights at Hibs included a 5-0 Fairs Cup thumping of Napoli in 1967 and reaching the 1969 Scottish League Cup Final, where they lost to Celtic. Finally he pitched up at Annfield Stadium (yes, really) to finish his career at Second Division Stirling Albion.

Bob was much more introverted than his more enthusiastic sibling, but they shared a love of hyperbole, hyping up the quality of their teams in the press to scare the opposition. Both were quick-witted and lacked sympathy for injured players. “I remember one of our players at Stirling was recovering from a dislocated shoulder,” recalls Smith. “As part of his exercises he had his back against the wall and his arms out in a crucifix position. Bob entered the room and the player said: ‘Eh boss, I feel like Jesus doing this.’ Bob quickly replied: ‘You might look like him, but Jesus was back among us in three days – there’s no sign of you ever getting better.’

“He would have gone to England as well if he’d been given the opportunity. But English clubs wanted Scottish managers to have played in the English league first. Bill had played down there – as had Matt Busby – but Bob hadn’t.”

Smith believes Bob would have replicated their success, too. “The dressing room would have instantly seen his strength of character and his deep knowledge of the game,” says Smith. “He was big enough and good enough to do any job – a marvellous man and a privilege to know.”

The blue half of Dundee agrees. Shankly has a stand named after him at Dens Park, voted for by the fans in 1999. With a more forward-thinking board at Dundee or Hibs, or an English club willing to look north for managerial talent, that affection would probably have been felt all around the world.

This feature first appeared in the March 2016 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Greg Lea is a freelance football journalist who's filled in wherever FourFourTwo needs him since 2014. He became a Crystal Palace fan after watching a 1-0 loss to Port Vale in 1998, and once got on the scoresheet in a primary school game against Wilfried Zaha's Whitehorse Manor (an own goal in an 8-0 defeat).