Fans are set to return, but clubs must repay them for their loyalty

Many fans waived refunds to help clubs survive during lockdown – it's time football clubs repay them

There were just 5,369 at Burnley, a mere 6,068 at Brighton and only 7,509 at Brentford. Leicester attracted a meagre 8,469. Manchester City, Chelsea and West Ham brought in more than 20,000 people apiece, but not by much. Only Arsenal, with a gate of 54,703 for their marquee match with Liverpool, attracted a supersized crowd for the opening day.

It was 1987/88, rather than 2021/22. Those small gates can be attributed in part to the lowly status of some of those modern-day Premier League clubs: Burnley were in Division 4 then, Brighton and Brentford in Division 3, Leicester and Manchester City in Division 2. Some were at older, smaller grounds.

Yet it also reflected a different reality: football was far less popular then. Or going to games was, anyway: despite cheaper ticket prices and though so few games were televised that attending fixtures was the only way of seeing the overwhelming majority, it was an era of hooliganism. English clubs were banned from Europe, some of the leading talents were employed abroad and the glamorous imports stemmed almost exclusively from Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

Some felt the national game was in terminal decline.

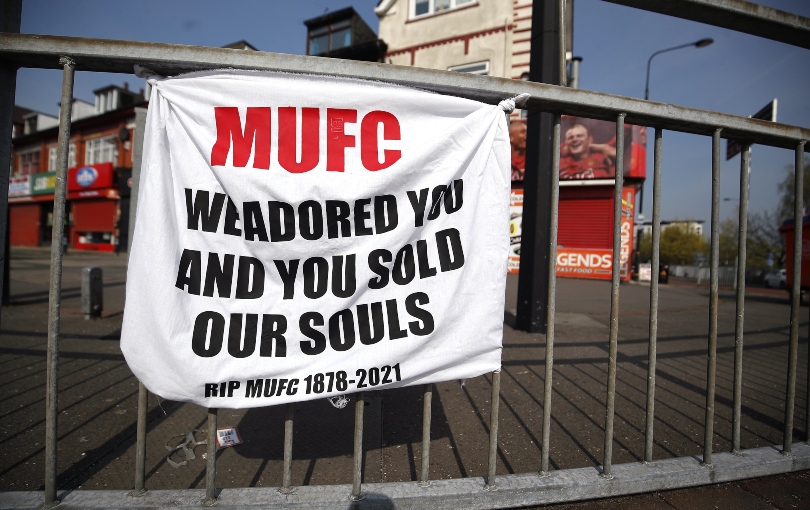

Much has changed since then. Over the last 17 months, football has both been reminded of the importance of fans, carried on without them and – in the shape of the Super League – tried to stage a coup that the overwhelming majority despised. It is the least controversial statement to say that football is better with fans and the least interesting people spent a year repeating it.

Some sections of the footballing industry have taken the fans for granted, some have looked for every extra opportunity to exploit them. The notion is that the fans are the constant and the most long-suffering definitely are. Their devotion is the guarantee. Many have paid their season-ticket fees for a year when they could not attend games or refused refunds.

As the supporters prepare to return – and in some cases have, with many a bumper gate for pre-season friendlies – there will be contrasting senses. Many will be looking to carry on where they left off in March 2020, relishing a return to normality, looking to erase memories of a dreadful time when grounds had an emptiness. Others may come back with renewed enthusiasm.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

There are historical precedents that support the theory that absence can make the heart grow fonder. Attendances boomed in 1946/47; those deprived of the chance to watch much football for the previous seven years relished its resumption. There are far more other ways of occupying our time now but the early evidence is that live sport retains a hold on affections: live anything, perhaps, after varying degrees of isolation meant there was precious little theatre or comedy or music. Plenty of clubs have reported their best figures for season ticket sales for years; others, particularly in the Premier League, were accustomed to selling them all.

It may be harder to put a number on those who are not returning. Some, sadly, are no longer with us. Some people’s health will have suffered. Others’ finances will: a loss of jobs and businesses could render football unaffordable to a number, while sadly, some of the pubs and cafes near grounds whose income depended on matchday attendances may no longer be around. Some will be nervous about packed concourses, trains, tubes or buses; if some football clubs and sporting bodies have not treated fans well enough, neither have some transport companies.

Rewind to early 2020 and there was the assumption the supporters would keep on coming. The 1980s was another world, not another era. Over the subsequent three decades, some clubs doubled or trebled in popularity (according to their gates; the global fanbases of some grew at a rather greater rate). The Championship had an average attendance of over 20,000 in 2018-19, the last complete season with crowds. The old Division 1 had an average gate of just under 20,000 in 1987-88.

The sport was facing an existential crisis without enough fans then. It has faced another without any (in person, anyway). It can be a reminder of how times can change and that nothing is certain to last forever. Football gave itself an added appeal in the intervening three decades, but it has to ensure it repays the returning supporters for their loyalty.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get six issues for just £9.99

NOW READ

QUIZ Can you name every Premier League club's stat-holders?

RETRO How the Premier League breakaway happened: The first season of 1992/93, as told by its heroes

Richard Jolly also writes for the National, the Guardian, the Observer, the Straits Times, the Independent, Sporting Life, Football 365 and the Blizzard. He has written for the FourFourTwo website since 2018 and for the magazine in the 1990s and the 2020s, but not in between. He has covered 1500+ games and remembers a disturbing number of the 0-0 draws.