Fifty years on: Was England's 1966 winning XI destiny, fate, or a chance affair?

It's a team ingrained in memory, but was it always destined to be that way? Fifty years on from that Wembley triumph, Paul Simpson explains how chance moulded Sir Alf Ramsey's legends of '66

Banks, Cohen, Wilson, Charlton, Moore, Stiles, Ball, Charlton, Peters, Hurst and Hunt is one of the most storied line-ups in English football history. Yet the process by which Sir Alf Ramsey created the side that beat West Germany 4-2 on July 30, 1966 was far from straightforward. England’s goalscorers in the Wembley final – Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters – didn’t even make their international debuts until 1966.

Off to a bad start

To understand how radically things changed, consider the first side Ramsey selected as England manager: a 5-2 defeat to France in a European Championship qualifier in Paris on February 27, 1963. This 11 does not roll off the tongue so easily: Ron Springett, Jimmy Armfield, Ron Henry, Bobby Moore, Brian Labone, Ron Flowers, John Connelly, Bobby Tambling, Bobby Smith, Jimmy Greaves and Bobby Charlton.

Seven of those players made the 1966 squad: Springett, Armfield, Moore, Flowers, Connelly, Greaves and Charlton. (It would have been eight but centre-half Labone withdrew to focus on his imminent wedding.) Yet only Moore and Charlton played in the final.

Ramsey certainly weighed up every option. From his disastrous debut to the last friendly before the World Cup, he selected 50 players. And the 11 that made history had only played three matches together… the quarter-final, semi-final and final.

The relationship between Moore and Ramsey was complex resembling, in part, that between disapproving father and errant son. Moore had enraged Ramsey by breaking a curfew on a 1964 tour of America

The first of that 11 to make himself indispensable was Bobby Charlton, the outstanding English footballer of his generation. With his pace, instant ball control and passing accuracy, Charlton could change games and had already scored 25 goals for England before Ramsey took charge.

Moore, meanwhile, was a natural leader; a composed, ball-playing centre-half, so gifted it is hard to see how Ramsey could have left him out. Yet Jimmy Greaves – this is a minority view – felt the West Ham skipper wasn’t much better than Wolves stalwart Flowers, whose run of 40 consecutive England games came to an end in April 1963. It is perfectly possible that, were it not for the Munich disaster, that versatile genius Duncan Edwards would have led England in 1966, instead of Moore.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The relationship between Moore and Ramsey was complex resembling, in part, that between disapproving father and errant son. Moore had enraged Ramsey by breaking a curfew on a 1964 tour of America. As the World Cup neared, his place was jeopardised by his failure to agree a new contract with West Ham. As a gentle reminder that even greats were dispensable, Ramsey played Norman Hunter at centre-half for three friendlies in 1966. He was not simply saving Moore for the finals as he smilingly boasted to Brian Glanville: “Pushed Bobby Moore!”

Changing of the guard

Ramsey began reshaping the team in his second match as manager, a 2-1 defeat to Scotland in April 1963, replacing Springett with Gordon Banks, the star of a Leicester side that nearly won the league in 1962/63. Banks couldn’t be blamed for either Scotland goals, and prevented at least two more. Ramsey tried other keepers – notably Blackpool’s Tony Waiters and Chelsea’s Peter Bonetti – but Banks was first choice.

Conceding five goals was hardly how Ramsey hoped to start his reign. As England came off the pitch, he asked captain Jimmy Armfield: “Do we always defend like that?” The inevitable changes at the back began in May 1963 when Ray Wilson featured at left-back in a 1-1 draw with Brazil.

A fiercely competitive, ball-playing full-back, Wilson was warned not to get ideas above his station by Ramsey: “You’ll play exactly how I want you to play,” said the Dagenham-born boss. The only threat to his position was injury – he tore his groin muscles off the bone in 1964 and didn’t recover until the spring of 1965.

Another injury – to Jimmy Armfield’s knee – created an opportunity for Fulham right-back George Cohen. He made his England debut at right-back in a 2-1 victory against Uruguay in May 1964 and had, as he modestly put it, a “steady game; nothing heroic”, but did precisely what Ramsey asked. In time, Cohen’s sprinting prowess would prove an asset in attack and defence.

Telling Charlton he was 'quite good', Sir Alf said: 'And I know you won’t trust Bobby Moore.' Seeing Charlton’s confusion, Ramsey explained that, when Moore surged upfield, he must fill the space left behind

Yet another injury disrupted Ramsey’s central defence. Maurice Norman, who played 17 out of 20 England games between April 1963 and December 1964, would have made the 1966 squad but broke his leg in five places in a 1965 friendly for Spurs and never played competitive football again.

Luckily, Ramsey already had his eye on Jack Charlton, giving him a characteristic pep talk: “I don’t always pick the best players you know. I have a system and I look for players to fit that pattern.”

Telling Charlton he was “quite good”, Sir Alf said: “And I know you won’t trust Bobby Moore.” Seeing Charlton’s confusion, Ramsey explained that, when Moore surged upfield, he must fill the space left behind. Good with his head and his mouth, Jack was one of England’s most vocal defenders, always organising, alerting, reprimanding. He played his first international in April 1965, a 2-2 draw with Scotland. In midfield that day was another debutant, Nobby Stiles.

Stiles remains the most controversial of the boys of ‘66. Much better on the ball than he was ever given credit for, he took no prisoners in the tackle. One shocking challenge on France’s midfield general Jacques Simon in 1966 led the FA to order Ramsey to drop him against Argentina. Ramsey’s response was to threaten to quit. Stiles had become integral to England, changing the shape of midfield.

Shape up

Ramsey’s World Cup winners are often described as a 4-3-3, but the formation was really 4-1-3-2 with Stiles anchoring in what we now call the ‘Makelele role’. That anchor could have been combative wing-half Tony Kay. Ramsey liked Kay, saying that playing him was “like putting a tiger in midfield”. The Everton star made his debut in June 1963, in an 8-1 demolition of Switzerland, and would have made the squad had he not later been banned from the game for life – and jailed – for helping to fix a match in 1961.

The FA ordered Ramsey to drop Stiles against Argentina. Ramsey’s response was to threaten to quit

With Stiles winning possession, it made sense for Bobby Charlton to move from the left wing into the centre, playing in the hole and exerting more direct influence on the game. Alongside Charlton, Ramsey would ultimately settle on Alan Ball (who made his debut in May 1965 in a 1-1 draw away to Yugoslavia) and Martin Peters (who played his first international, a 2-0 win against the same opposition, in May 1966).

Why did Ramsey take so long to pick Ball and Peters? In 1963/64, he experimented with ball-playing attackers George Eastham and Johnny Byrne. An elegant midfielder, with good close control and a subtle user of the ball, Eastham made the 1966 squad but never played. The Arsenal star may have paid the penalty for missing chances in a 2-0 victory against Spain in December 1965. Nine of the side that beat Spain would win the World Cup final. (The other absentee was Joe Baker, who though born in Liverpool, was about as Scottish as haggis and didn’t make the squad.)

Despite the ‘Wingless Wonders’ cliché, Ramsey didn’t immediately give up on wingers. Blackburn’s Bryan Douglas was unlucky. He scored three goals in three games as outside right under Ramsey but was deemed defensively unsound. Ramsey later tried Connelly, Terry Paine, Ian Callaghan and Derek Temple.

Peters came into the reckoning almost as late as Marcus Rashford before Euro 2016. The West Ham midfielder’s outstanding debut, in which he almost scored twice and created many chances, helped him gatecrash the squad

The England boss didn’t know what to make of Liverpool winger Peter Thompson. Tricky enough on the ball to be dubbed the ‘white Pele’, Thompson was tactically, as Bill Shankly said, more of a “white Nelly” and didn’t make the squad. Yet three wingers did: Paine and Callaghan, who could switch to midfield, and Connelly, a traditional winger. All three featured before Ramsey reverted to 4-1-3-2 against Argentina with Bobby Charlton, Alan Ball and Peters in midfield.

Ball’s obedience, tireless running and passing ability impressed the England boss. The worry was Ball’s temperament – he got booked a lot and, in one U23 international, threw the ball at the referee, but he kept his cool during the finals.

Peters came into the reckoning almost as late as Marcus Rashford before Euro 2016. The West Ham midfielder’s outstanding debut, in which he almost scored twice and created many chances, helped him gatecrash the squad. Industrious, two-footed, and a shrewd anticipator of opportunities, Peters scored England’s first goal in the final, from an attack started by Ball.

Hurst's destiny

Greaves was virtually guaranteed his England place. He had scored 21 goals in 29 games for Ramsey and would probably have played in the final if his leg hadn’t been gashed against France

From February 1963 until July 1966, Greaves was virtually guaranteed his England place. He had scored 21 goals in 29 games for Ramsey and would probably have played in the final if his leg hadn’t been gashed against France. That said, striker and manager never really got on. Sir Alf felt Greaves was disrespectful, a bad influence on Moore and suspected the striker of mocking his accent, which he was incredibly touchy about. Yet even Ramsey would have found it tough to drop a match-fit Greaves for Hurst, who had played just five England games before the finals.

After Ramsey recalled Roger Hunt in June 1963, the Liverpool forward seemed Greaves’s most likely strike partner. Other forwards – Tambling, Fred Pickering Frank Wignall, Barry Bridges, Alan Peacock and Mick Jones – were tried and found wanting. Spurs’ Bobby Smith fell out of the reckoning when he gained so much weight after injury that the Daily Express called him “Blobby Smith”. When Hunt was given the No.21 shirt for the 1966 finals, he feared he wouldn’t be playing but, like Hurst (who had forced his way into contention with 23 goals for West Ham in 1965/66), he was the kind of hard-working goalscorer Ramsey approved of.

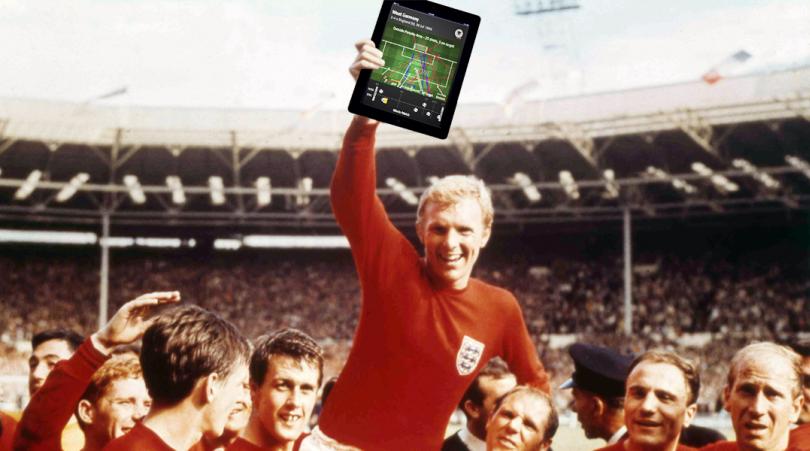

The 1966 World Cup Final like you've never seen it before

Hunt and Hurst’s movement off the ball gave England more attacking options and created space for Bobby Charlton to run into from deep. England no longer had to pick their way through defences, they could go over them, or round them, hitting crosses for Hurst to score or hold the ball. This tactic eventually undid Argentina in the quarter-finals, Peters crossing for Hurst to ghost in and head the only goal.

For all of Greaves’s glittering talent, his game didn’t suit Ramsey’s 4-3-1-2. Despite fierce press debate, he never seriously contemplated recalling Greaves. It was a gutsy, if characteristic decision – as Hurst said later, to Dave Bowler, author of Three Lions On The Shirt: “What would have happened if we’d lost 3-0 and Roger and I had missed a couple of sitters each?”

In hindsight, team building always looks inevitable. Yet the process can be complex, tortuous and haphazard. It is not too outlandish to suggest that, but for fraud, injury and tragedy, the England team that made history against West Germany could have been: Banks, Armfield, Wilson, Norman, Edwards, Kay, Eastham, Charlton, Ball, Greaves and Hunt.