Flags of our fathers: why Genoa vs Sampdoria is more than a game

The Genoa derby is rarely violent but enjoys a heady mixture of South American passion, 'British spirit' and Italian fan choreography, as Frank Dunne found out for the February 2009 issue of FourFourTwo...

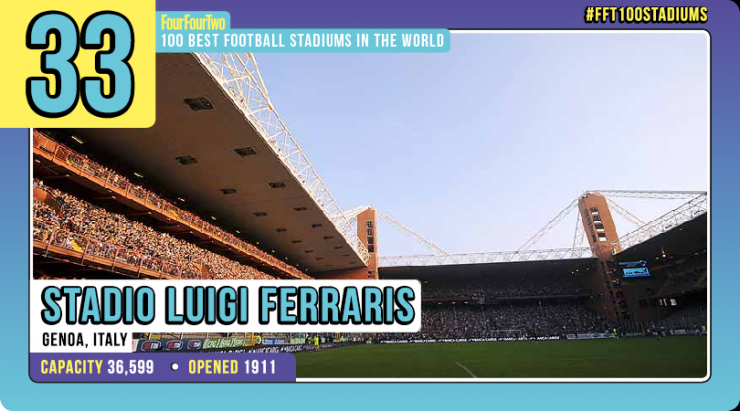

On first impressions, the Genoese derby seems like many others in Italy: violent. “Kill them, kill them,” sing the Genoa fans. “Genoa, Genoa, vaffanculo” – “F**k off, Genoa” comes the reply from their Sampdoria counterparts. Throw in the fact that it’s still an hour and a half until kick-off on a freezing cold December evening and the port city’s Stadio Comunale Luigi Ferraris is already full to 36,536 capacity, and it’s enough to make FourFourTwo wonder what calibre of lunatic we’re in the company of.

But in the Derby della Lanterna (the ‘Derby of the Lantern’), everything is not at it seems. Nearly an hour later, the volume inside the ground goes up several decibels as the Samp keeper Luca Castellazzi comes out for his warm-up. The Samp fans on the South Stand break into their anthem, a catchy 1975 pop song by the late singer-songwriter Rino Gaetano called Ma il cielo e sempre piu blu – ‘But the sky gets bluer and bluer’ – a hymn to eternal optimism and a nod to the colour of Samp’s shirt. Now both teams are out warming up and the noise is deafening. As Samp go through their stretches, Antonio Cassano gestures to the South Stand to raise the roof.

On first impressions, the Genoese derby seems like many others in Italy: violent. “Kill them, kill them,” sing the Genoa fans. Sampdoria fans reply “Genoa, Genoa, vaffanculo” – “F**k off, Genoa”

In the North Stand, Genoa fans greet their own hero, the Argentine striker Milito, with choruses of “Olè, Olè, Olè, Olè, Diego, Diego,” As the ‘away’ team, they only have 11,000 fans to Samp’s 26,000 but for the moment they are out-singing their rivals.

Just before kick-off, something extraordinary happens. In the North Stand, all the flags and banners are lowered and the chanting stops. Briefly, it becomes a wall of mute heads, like the cardboard crowds sometimes used by clubs during stadium reconstruction. Then, suddenly, the entire stand is transformed into one giant, shimmering flag with a white background and horizontal stripes of Genoa’s colours – scarlet and royal blue.

In response, the remaining two thirds of the stadium mutates into a sea of fluttering Samp colours, with every fan raising a one-metre square blue flag with horizontal stripes of white, black and red.

In a country where even important Serie A matches are often played in front of half-empty stands, only the big derbies – like Inter vs Milan and Roma vs Lazio – still feature this level of choreographed support

It’s a spine-tingling sight and you will see nothing like it in the Premier League. It’s a reminder of how things used to be in Italian stadiums before the violence – and the repressive measures used to counter it – kicked in during the 1990s.

In a country where even important Serie A matches are often played in front of half-empty stands, only the big derbies – like Inter vs Milan and Roma vs Lazio – still feature this level of choreographed support.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But the Genoa derby is special, perhaps unique in Italy. Despite the intensity of the rivalry, it rarely descends into the hatred that marks other duels around the peninsula.

Before this evening’s match, the bars along Corso Alessandro De Stefanis, which runs the length of the stadium, are packed, mostly with Samp fans but with plenty of Genoa fans too. After the match, despite the no-holds-barred nature of the contest and a controversial outcome, the street leading down the hill to town – Via Canevari – is full with fans of both teams. It is a molten flow of people and scooters, a cacophony of horns with barbed comments flying but there is no violence.

Both clubs have their Ultras – The Sampdoria Ultra, founded in 1969, was the first group to use the name – but they tend to represent the traditional idea of organised support and have not developed the militant minorities, fixated with fighting other fans and the police, which can be found in other cities. Fans of both clubs have worked hard to avoid being contaminated by political extremism, although there is a worry that the extreme Right has been infiltrating the terraces in recent years.

There are common interests which unite the fans. One of these is the ‘No to Modern Football’ movement, against the commercialisation of the game and the splitting up of the traditional calendar.

It’s different to the other derbies in Italy. The rivalry between the two sets of fans is based on mickey-taking, on pranks, like organising mock funerals for the opposition. It’s the least nasty of all the derbies and I’ve rarely seen any violence

Fans from the two clubs also stood side by side on two moving occasions. The first was for the funeral in October 1993 of Samp president Paolo Mantovani. The second for the funeral of 24-year-old Genoa fan Claudio Spagnolo, who was killed by an AC Milan supporter before a Genoa-Milan match in January 1995.

Italy coach Marcello Lippi was involved in the derbies in Turin and Milan as a coach and in Genoa as a player, as libero from 1970 to 1980. “It’s different to all the other derbies in Italy,” he says. “The rivalry between the two sets of fans is based on mickey-taking, on pranks, like organising mock funerals for the opposition. It’s the least nasty of all the derbies and I’ve rarely seen any violence.”

Throwing down the gauntlet

The commonly held view of the Genoa derby, then, is that it is Latin American in its passion but played and watched with what Italians call “a British spirit”. The only problem this evening is that someone has forgotten to tell the players. In the first minute, Samp midfielder Daniele Franceschini steams into the back of Milito. A few minutes later Cassano is sandwiched and goes down holding his face, as if head-butted.

The pattern of the first half has been established: lots of fouls, little football. Everyone who gets tackled goes down and rolls around, one set of fans or another explodes in anger, the “injured” player’s team-mates come charging over and pushing and shoving breaks out.

There are 33 fouls in the first 35 minutes – a Serie A record for the season. The rumour circulating around town in the days before the match that the teams had agreed to settle for a draw is quickly forgotten. By the end of the match, there will be 57 fouls and 11 yellow cards. The only cool head in the stadium is that of referee Stefano Farina. But the Samp fans have been warning all week that the Genoa-born ref can’t be trusted. He’s a Genoa fan, they claim, and he is out to do Samp.

NEXT: "I want pandemonium in the stadium"

The feisty atmosphere could be put down in part to the inflammatory remarks of Samp talisman Cassano in an interview broadcast on the Friday before the game. “We’re better than them, I’m sure of that,” is his opener. “They should open their ears; they must know that we are better. There will be more of our fans and as soon as the Genoa fans open their mouths we have to shout them down.

I want pandemonium in the stadium. If I wake up in the right frame of mind, they should be afraid. In the last derby their players were white with fear. Their sunlamps did them no good

"I want pandemonium in the stadium. If I wake up in the right frame of mind, they should be afraid. In the last derby their players were white with fear. Their sunlamps did them no good. I want to remind the Genoa fans that I have played in derby games in Bari, Rome and Madrid and I’ve always scored.”

As far as throwing down the gauntlet goes, it doesn’t come much more emphatic than than. But Milito, ‘El Principe’, isn’t falling for it. The taciturn Argentine is the opposite in terms of personality to the irrepressible Cassano and his reply is typically understated: “I dream of scoring the decisive goal in the derby, but I know it won’t be easy.”

Always there, impossible to ignore

Cassano’s bluster is seen is a classic example of Samp’s inferiority complex. In his book, The Infinite Derby, local football writer Renzo Parodi suggests that for Samp fans, Genoa is like the gigantic mother figure in the 1989 Woody Allen film Oedipus Wrecks – always there in the background, impossible to ignore.

The haughty Genoa fan, on the other hand, simply pretends that Sampdoria doesn’t exist. Many pride themselves on never using the name and club president Enrico Preziosi tends to refer to “the other club”. Genoans are “absolutists”, Parodi says, in that they only ever think about one club. Samp fans, on the other hand, are “relativists – a win for Samp is never enough unless it is accompanied by a defeat for Genoa”.

For all the talk about an untypical derby, there have been times when the rivalry has spilled over into something unsavoury and Parodi warns that it is unwise to “insist on the concept of Genoa as a happy footballing island”. There were pitched battles between the two sets of fans in May 1989 and as recently as September 2007.

There is a theory that the enmity between the people in the east of the city, who tend to support Genoa, and those to the west, who root for Samp, goes back to pre-Christian times, to the Second Punic War between 218BC and 201BC, when the westerners sided with Carthage while the easterners sided with Rome. Such theories are impossible to stand up but what is not in doubt is the date of the first derby between Sampdoria and Genoa.

On November 3, 1946, in front of 40,000 fans at the Luigi Ferraris, Samp won 3-0 and were 3-2 winners in the return game on March 30, 1947. These were the first of the 80 titanic battles at the ground which preceded tonight’s fixture. Samp are well ahead on victories – 30 to 17, with 33 draws – but Genoa, usually the underdog, often had their day when it was least expected. Like the famous game of November 25, 1990.

Branco fired a 25-yard screamer past Samp keeper Gianluca Pagliuca to settle the game. The next day, the scene of the goal was reproduced on Christmas cards for Genoa fans to send to their Samp ‘cousins’

It had been 13 years since Genoa had beaten Samp, who were top of the league and playing “at home” that day. A disputed penalty for Samp, scored by Gianluca Vialli, cancelled out an early strike by Genoa captain Stefano Eranio, appearing to dash any hopes of an upset. But then Genoa’s Brazilian left-back, Branco, fired a 25-yard screamer from a free-kick past Samp keeper Gianluca Pagliuca to settle the game.

The next day, the scene of the goal was reproduced on Christmas cards for Genoa fans to send to their Samp ‘cousins’. That year, Genoa went on to finish fourth with 40 points, the club’s best post-war showing. But fans of the Blucerchiati had the last laugh. Led by Vialli and Roberto Mancini, Samp won the Scudetto with 51 points.

NEXT: The English magician who founded football in Italy

The English magician

Anyone looking at the recent stats could be forgiven for thinking that Samp are the Manchester United of the city and Genoa the Manchester City. But the statistics only tell half the story and to understand the rivalry between the two clubs, and their respective places in Italian football folklore, you have to go back to the late 19th Century.

Genoa was the first Italian football club. The Genoa Cricket and Athletic Club was created on September 7, 1893 by a group of English gentlemen

Genoa was the first Italian football club. The Genoa Cricket and Athletic Club was created on September 7, 1893 by a group of English gentlemen in the British Consulate, in the presence of the Consul, Sir James Alfred Payton.

Football wasn’t part of the club’s original agenda but that changed with the arrival in 1897 of James Richardson Spensley, a doctor with the British navy. Referred to as do mego ingleise – ‘the English magician’ – Spensley led the team to the first ever Italian league title, a one-day affair played in 1898. The following year the name was changed to Genoa Cricket and Football Club, the name it still bears to this day.

Born in Stoke Newington, London, in 1867, Spensley became known in Italy for his sense of fair play and, ironically, it was probably this which cost him his life. On September 26, 1915, during the Great War, he was injured while tending to enemy wounded, dying shortly afterwards in a hospital in Mainz, Germany. Spensley’s exploits cemented the English connection at the club but it was another Englishman, William Garbutt, who would make the most indelible mark on Genoa’s history.

Between 1898 and 1924 Genoa won the league nine times. Their fans see themselves as the aristocrats and Samp, founded in 1946, as the upstarts. In every derby, the North Stand features a banner which says simply: 1893

Garbutt was born in Hazel Grove, Stockport, in 1883, and played professional football for Woolwich Arsenal and Blackburn before retiring due to injury. When recruited to run Genoa CFC in 1912, aged 29, he became the first professional manager in Italian football. It was his period as coach, from 1912 until 1927, that was to bequeath to Italian football the term ‘Mister’, which is how Italian players at all levels have addressed their coaches ever since.

Under Garbutt’s leadership Genoa became the dominant team. Between 1898 and 1924 the team won the league nine times. So it is not surprising that Genoa fans should see themselves as the aristocrats and Samp, founded in 1946, as the upstarts. In every derby, the North Stand features a banner which says simply: 1893.

The Manchester of Italy

Despite its pre-eminence in those early years, Genoa CFC did not have a monopoly on football in the area. Two gymnastics clubs – Andrea Doria in the city and Sampierdaranese to the west – were evolving into football clubs. The football section of the Andrea Doria gymnastic club was founded in 1901 by Francesco Cali, a Sicilian who had moved to Switzerland in his youth. He transferred to Genoa, playing a season for Genoa CFC before defecting to Andrea Doria. He would be the first ever captain of Italy, in 1910.

While Andrea Doria’s players were drawn from the city, Sampierdarenese were outsiders. Search for ‘Sampierdarena’ online and you will see that it is now a suburb of Genoa, but at the turn of the 20th century it was a separate town, one with such a rapid growth of heavy industry that it was nicknamed ‘The Manchester of Italy’. At the western end of Genoa’s harbour, halfway between Sampierdarena and the centre of the city, stood a lighthouse built in the 16th century. It is from this lighthouse, which is still there, that the name ‘The Derby of the Lantern’ is derived.

The first derby match in the city is thought to have been that between Genoa and Sampierdarenese in 1899. Genoa won, though the score wasn’t recorded

The first derby match in the city is thought to have been that between Genoa and Sampierdarenese on March 27, 1899. Genoa won, though the score wasn’t recorded.

The rivalry between Genoa and the two newcomers was real from the outset. Whereas Genoa CFC was a deeply English, upper-middle-class institution, these two clubs were Italian to the core and resolutely working class. One story about the red and black stripes on Sampierdarenese’s shirt is that they were a tribute to the anarcho-syndicalist movement.

These two clubs would merge twice in the first half of the 20th century. The first merger was imposed on the clubs in 1927 by Italy’s Fascist regime as part of a restructuring of the old leagues in the north and south of the country into the first national league. Dictator Benito Mussolini gave the new team the name ‘Dominante’ and had them play in black shirts with green trim.

After the war there were powerful voices among the two factions in the club to go back to the original identities. However, due to fears that Sampierdarenese did not have the economic resources to go it alone, a new club, Unione Calcio Sampdoria, was born on August 12, 1946. The club shirt would have the blue of Andrea Doria with white, red and black stripes to represent Sampierdarenese. The new name was decided after heated discussion and for a long time was set to be Doriasamp.

Once you know the history of the clubs, the banners inside the stadium make more sense. The 1893 flag has a clear message: we are the thoroughbreds, you’re the mongrels. Among the myriad Union Jacks and Argentina flags, another Genoa flag taunts Samp with Ospiti di Genova – ‘Guests of [the city of] Genoa’.

As the second half gets underway, banners of a more provocative nature start to appear. ‘Cassano: illiterate and covered in acne,’ reads one. Under Italy’s anti-hooligan measures, all banners have to be approved by the police before the game. But there is always a way around the rules and just to emphasise the point, with a wry touch, the next banner that goes up on the North Stand says: ‘Unauthorised banner’.

‘Cassano: illiterate and covered in acne,’ reads one banner. Under Italy’s anti-hooligan measures, all banners have to be approved by the police before the game. But there is always a way around the rules and just to emphasise the point, with a wry touch, the next banner that goes up on the North Stand says: ‘Unauthorised banner’

While the crowd was distinctly more interesting than the match in the first half, in the second half a game of football breaks out. On 49 minutes, Milito makes a yard of space for himself in the area and bullets a header into the top corner of the net. Two minutes later Samp score but the goal is ruled out for offside.

Less than an hour gone and the Genoa players are time-wasting already, going down with cramp and kicking the ball away at free-kicks. Samp are throwing the kitchen sink at Genoa and on 80 minutes they finally make the breakthrough. A free-kick is hoisted into the box, nodded on and poked in at the far post by Hugo Compagnaro.

Cue bedlam. But the players have hardly begun to celebrate when they notice the linesman’s flag and Farina disallows this one too. The words “Farina! We bloody knew it’, are etched into the face of every Samp fan in the stadium.

In the 90th minute Cassano goes bananas. He runs the ball out of play and when the (same) linesman flags for a goal-kick, he boots the ball straight at the linesman. He gets a yellow card but it could have been red. There are five minutes of injury time and the fourth official, Roberto Rosetti, is struggling to keep respective benches apart. But then it’s over and while Cassano collapses to his knees, the Genoa players are celebrating like they’ve won the World Cup final.

The Derby of the Lantern has finished Samp 0, Genoa 1. Cassano 0, Milito 1. South Stand 0, North Stand 1. Christmas cards showing Milito’s goal, which Genoa fans will be sending to their blue ‘cousins’, are available on the internet within hours.

This feature first appeared in the February 2009 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!