Football in the pits: when Manchester United & Co. were fuelled by Britain's mines

Today's up-and-coming youngsters needn't worry about a more lucrative second income – but that wasn't always the case, writes Richard Edwards...

It wasn’t the usual welcome for the miners of Kellingley Colliery. As they returned to the surface, soot covered and sporting their orange high-vis jackets, they were greeted with a phalanx of photographers that wouldn’t have looked out of place on the red carpet of the Star Wars premiere just two days previously.

For a brief period these miners were celebrities, albeit ones present at an unwelcome celebration. December 18, 2015, marked the end of deep coal mining in Great Britain – and the end of an industry which has its roots firmly entrenched on these shores.

Back in my day

There was a self-conscious cult of northern aggression, which applauded the violent antics of some players

It’s doubtful that too many modern-day footballers were paying a huge amount of attention to those unfortunate enough to have lost their jobs at Kellingley just a week before Christmas. With the festive period coming up they were, of course, far more concerned with ensuring they were in peak condition for football’s silly season.

Their ambivalence would be easy to understand given that that the almost-inextricable links that existed between one of the UK’s biggest industry and the national game have all but disappeared.

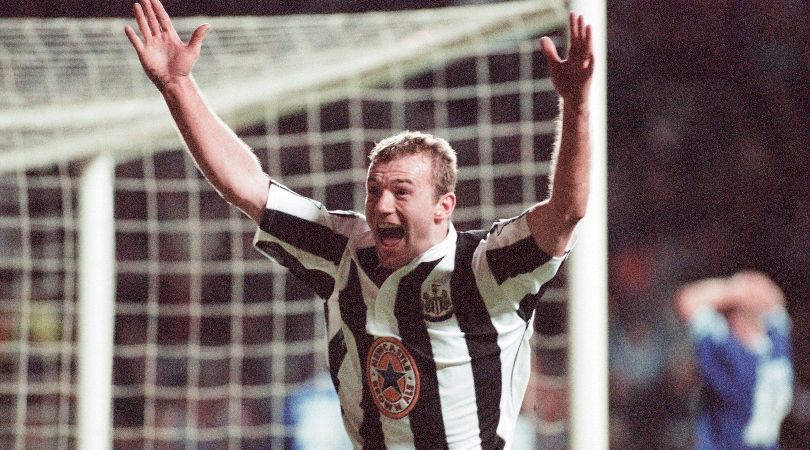

The fact remains, though, that the coal mining communities of North Wales, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Durham didn’t simply make up a large proportion of the crowd on a Saturday afternoon in days gone by – the pits also nurtured a large amount of the talent on show.

“Clubs like Barnsley, fed by miners from the nearby coalfield, abounded in stories polished in the telling of men working double shifts and walking 20 miles to play a match,” wrote David Winner in Those Feet, An Intimate History of English Football.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The years they spent underground not only served to build up the strength and stamina of these players, they also helped mould the character of the teams they played in.

“There was a self-conscious cult of northern aggression, which applauded the violent antics of some players,” wrote Winner. “Plenty of teams had a hard man but some clubs, it was widely believed, made a fetish of aggression.”

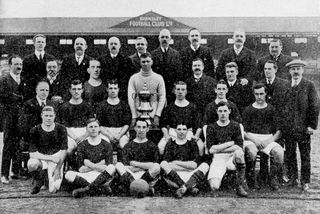

You didn’t, for example, want to mess with the miner-strewn Barnsley side that made it to the 1912 FA Cup Final – a team who took no prisoners and apparently relished kicking players as hard and as high as they could.

United's gain

I was assistant manager in a coal mine – earning much more than I ever did for Manchester United

In many ways the decline of the mining industry has been inversely proportional to the rise of football in the post-war period. Bill Foulkes, a Busby Babe who won the European Cup final on a memorable Wembley night in May 1968, began his career in the pits – and was paid more handsomely for doing that than he was playing for the country’s pre-eminent side.

In The Busby Babes, Men of Magic, Manchester United legend Foulkes described how his entire life was shaped by his experience of working deep underground in conditions that few of us could now imagine.

“I was assistant manager in a coal mine – earning much more than I ever did for Manchester United,” he said. “I would do a full shift down the mine, starting at 5.30 in the morning and finishing at 2.30 in the afternoon. I would take a shower at the pithead, grab a bite to eat and then frequently have to dash for a train to Manchester. With a life like this I was fitter than many full-time professional footballers.”

Two years before Foulkes helped United beat Benfica, Jack Charlton had experienced the joy of being a footballer on top of the world. Watching on was his father, who, legend has it, spent the morning of the 1966 World Cup Final doing a shift underground.

Charlton himself endured a brief stint as a miner before signing for Leeds as a teenager.

“There is a picture of him taken afterwards, coming to the surface,” wrote Bobby Charlton in the first part of his autobiography, My Manchester United Years. “He is wearing a helmet and the expression on his face shows how bemusing and dispiriting he found the experience.”

Unlike a great many others from the area the Charlton boys called home, neither would ultimately have to contemplate a career spent in some of the most appalling conditions imaginable.

It’s a measure of the almost-inevitable career path that most in the area took, though, that Charlton’s first school, North Hirst Primary School in Ashington, boasted a display of mining implements that included picks, shovels and a helmet – offering those within its care a pointer of where their future lay.

Local dispute

During the bitter miners’ strike of the mid-80s, clubs like Mansfield and Chesterfield were very much shaped by the dispute

That option, of course, is no longer open despite the fact that Kellingley has coal reserves that could potentially last a further 25 years. But while the industry itself has all but died, the rivalries that it forged still live on.

During the bitter miners’ strike of the mid-80s, clubs like Mansfield and Chesterfield were very much shaped by the dispute – and the enmity that built up during that time still endures.

Situated just 10 miles apart, both towns had very different experiences of the strike, with Derbyshire’s miners striking throughout and Nottinghamshire’s miners returning to the pit before the dispute had reached its inevitable conclusion.

With few other platforms available to express their contempt, a football fixture offered the perfect opportunity for both towns to display it. Although mining stopped in both areas as far back as 1992, the fixture is still as hostile today as it was back then, with shouts of ‘scabs’ ringing out across the terraces from the first minute to last.

“Unless you are from either town or you have been at either club for a long time you may not be aware of the rivalry,” Ritchie Humphreys, then of Chesterfield, told the Daily Mail in 2013. “It’s a long time ago now but obviously it still doesn’t sit well with a lot of people.”

The closure of Kellingley was a final blow for an industry which, perhaps more than any other, came to define entire regions of this country. The mines are long gone but the football clubs who owe their past to them are still very much present. For the communities that have been ripped apart, a giant hole remains. It’s one that football can only partially fill.

RECOMMENDED More retro tales from the FFT archives