FourFourTwo’s 20 favourite cult clubs of all time: is yours in there?

With Johan Cruyff's Barcelona Dream Team lifting the European Cup on this day in 1992, we reflect on a few more sides that have a special place in our hearts...

Barcelona (1990-94)

Why you should care: In 1986, a wiry 15-year-old youth-teamer turned up to his prueba de la muneca – or ‘doll’s trial’ – to perform a series of tests to determine which La Masia starlets would be retained, based on whether they’d grow up to measure 1.80m (5ft 9in). “I’ll be taller than 1.80m!” said the kid. “I’m going to be a professional footballer.”

It took Johan Cruyff’s vision to change La Masia into the paragon of skill-over-physicality philosophy from 1988 – Lionel Messi, Xavi and Andres Iniesta are all under 1.80m – realising a production line of technical waifs which turned Barcelona into football’s aesthetes.

Dubbed the Dream Team after sealing the Catalans’ maiden European Cup win in 1992, the side Cruyff built also won four consecutive La Liga titles from 1990/91.

Koeman, Laudrup, Stoichkov and later Romario – this is the team Blaugrana fans get misty-eyed about, not the 2009 or 2011 vintages with those three Lilliputians. “Cruyff reinvented the concept of football in Spain,” centre-back Miguel Angel Nadal once told FFT. Oh, and that ecstatic 15-year-old? You might have heard of him: Josep Guardiola Sala.

And finally… Vice-president Joan Gaspart promised to swim in the Thames if Barça won in 1992. “I could’ve said I’d go to breakfast with the Queen,” he said, drenched at 4am.

Parma (1992-99)

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Why you should care: Football fans of a certain generation are thrilled to see Parma back in Serie A. In the 1990s they produced two great teams, the first oozing cool despite being backed by a multinational company in Parmalat; the second boasting indescribable individual talent.

In 1992, Parma got their first taste of silverware and liked it. So, the Coppa Italia in the bag, they brought in a 22-year-old forward from Colombia. For many, Tino Asprilla embodied this flair-filled side – either Asprilla or the brilliant but ballooning Tomas Brolin – although a year later, Gianfranco Zola arrived. In ’94 Fernando Couto and Dino Baggio rocked up, the latter scoring in each leg of Parma’s UEFA Cup final win over Juventus. Hristo Stoichkov landed in ’95 and a teenage Gigi Buffon kept a clean sheet on his debut against a Milan team with two Ballon d’Or-winning strikers.

Two factors raise their cult appeal abroad: Channel 4 launching Football Italia in ’92, and unfulfilled potential. Parma weren’t loveable losers. They won eight trophies, their only eight trophies, within a decade, but lost the 1996/97 Serie A title to Juventus by two points.

And finally… Boss Alberto Malesani once visited Barcelona to watch Johan Cruyff take training... while on his honeymoon.

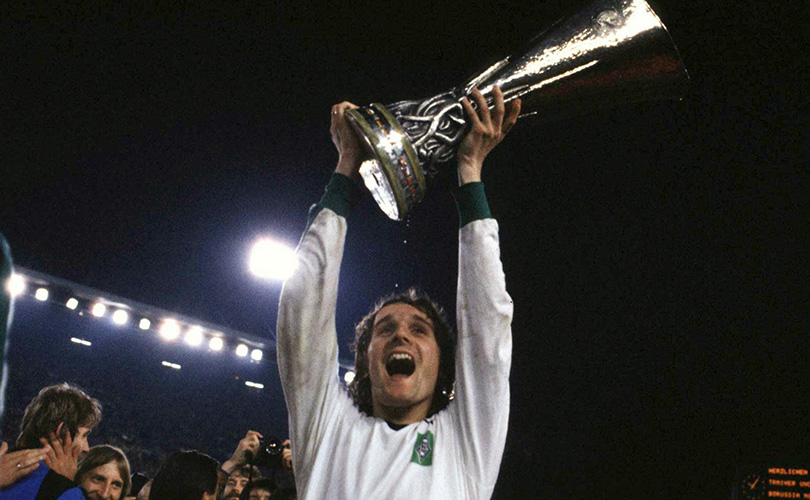

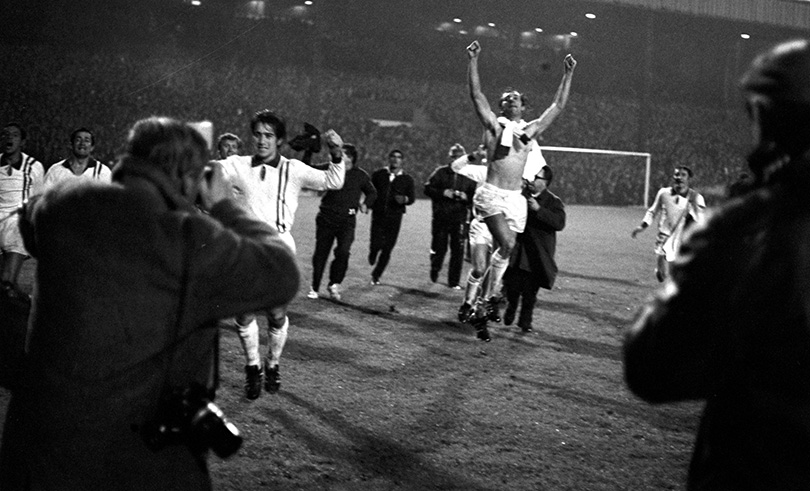

Borussia Monchengladbach (1970-79)

Why you should care: Intangibles define a cult football team. A cool factor, legacy or revolutionary approach tops an interminable drudge towards success. So does appearing in a folk song, the cultier the better.

Step up Borussia Monchengladbach and Half Man Half Biscuit. Admittedly, the Merseyside folk rockers simply wanted a really long team name to help them complete the “Supercalifragilistic Borussia Monchengladbach” lyric on seminal The Bastard Son of Dean Friedman, but chief songwriter Nigel Blackwell was a former fanzine editor, spellbound by Die Folen’s defeat to Liverpool in the 1977 European Cup Final.

They featured gloriously attacking youngsters, many recruited from within a 10-mile radius of the German city near the Dutch border. Luxuriously talented (and coiffed) playmaker Gunter Netzer captured everyone’s imagination, with full-back attack dog Berti Vogts and pathological winner Jupp Heynckes the steel behind five Bundesliga crowns (including three in a row from 1975) and two UEFA Cups. They may have lost to Liverpool, but it’s not hard to see why Gladbach so enthralled HMHB.

And finally… Netzer was a law unto himself. Benched for the 1973 German Cup Final against Cologne because he’d revealed he was off to Madrid, the greengrocer’s son subbed himself on in extra time. “I’ll go and play now,” he told coach Hennes Weisweiler, before scoring the winner.

Tranmere Rovers (1990-95)

Why you should care: FFT makes no apologies for successive mentions of Half Man Half Biscuit, who refused to perform on Fridays so as to never miss Tranmere home matches. They even turned down an appearance on legendary yoof music show The Tube despite Channel 4’s offer of a helicopter to the north east studio from Prenton Park. “Friday night and the gates are low,” they sang on the eponymous single, “bastard slip of a sub’s ruined my weekend.”

At the beginning of the ’90s, HMHB had good reason for keeping up their Wirral appearances. After winning promotion to the Second Division in June 1991 – via the play-offs, their fourth trip to second home Wembley in 12 months – Rovers recruited John Aldridge from Real Sociedad for £250,000. Two years later, ultimate cult footballer Pat Nevin – who once had a column in the NME – arrived, forming a glorious front four in which he and John Morrissey flanked Aldridge and Chris Malkin.

“I can’t promise anyone success,” said boss Johnny King, “but I can promise a trip to the moon.” In the end he delivered the former, if not the latter. Three times they reached the play-offs and a shot at promotion to the Premier League, only to fall short.

And finally… It wasn’t just HMHB who had the music world gripped. King likened Rovers to a “deadly submarine” (compared to Liverpool or Everton’s “Queen Mary ocean liner”), so Elvis Costello used the nickname for his appearance on Baddiel and Skinner’s Fantasy Football League.

Lazio (1972-77)

Why you should care: By the time Rob Newman and David Baddiel became the first comedians to sell out Wembley Arena in 1993, they’d only talk to each other on stage via their “That’s you, that is” university professor trope.

Internal hostilities were no less frenzied in the Lazio dressing room during the mid-70s. “Everyone detested each other,” recalled goalkeeper Felice Pulici. Legend has it, the squad would only wear shinpads in training – not bothering for games – so violent were the sessions. “By the time you played a league match, it felt like a friendly,” quipped midfielder Luigi Martini.

It didn’t help that, to ease boredom on away trips, the tooled-up players started a part-time shooting club to have a pop at “things in bushes and bits of furniture”. Striker Giorgio Chinaglia destroyed a training ground shed with his 6.5mm rifle, specifically bought because it was the same as the gun which Lee Harvey Oswald used to assassinate John F Kennedy a decade earlier. In 1977, midfielder Luciano Re Cecconi pretended to hold up a friend’s jewellery store, shouting: “Everybody stop, this is a raid!” The owner shot him. “It was a joke, it was a joke,” cried the fatally wounded Re Cecconi.

In between the gun-toting japery, a forward-thinking football team broke out – which won Serie A in 1973/74.

And finally… This Lazio vintage did little to dispel the idea that the Eagles were right-wing sympathisers. Martini became a minister for the neo-fascist Alleanza Nazionale party.

Middlesbrough (1996-97)

Why you should care:FFT first fell for this Boro team in 1994 when manager Bryan Robson turned up to a photo call announcing his Riverside arrival dressed half in football kit and half in a suit. But it was two summers later that Teesside truly delivered on its promise.

Signing £7 million Fabrizio Ravanelli – fresh from scoring in Juventus’s Champions League triumph against Ajax – and Brazilian midfielder Emerson was one of the Premier League’s biggest transfer coups for a side which already possessed pint-sized Samba waif Juninho buzzing about in a six-sizes-too-big bedsheet. And Craig Hignett and Phil Stamp.

The White Feather’s opening-day hat-trick in a 3-3 draw with Liverpool proved prophetic for a Boro squad which scored and conceded with equal zeal. They lost just one of their first six league matches, but won only twice from mid-September until early March, staring relegation in the face.

Despite murmurings of discontent off the pitch – “they have a Ferrari, but no garage,” huffed self-referencing Ravanelli of the battered team bus – Boro proved the talent was there by reaching both cup finals. They lost both, and then went down.

And finally… Ravanelli and Neil Cox had a scrap just before walking out onto the Wembley pitch. “Rav was shouting at Neil at the back of the bus, reaching across players to have a fight with him,” remembered Robbie Mustoe. All while comedian Stan Boardman was trying to perform a gig at Robson’s insistence to relax the players. As you do.

Deportivo La Coruna (1999-2002)

Why you should care: Deportivo in the late-90s were the footballing version of Katherine Heigl in rotten 2008 chick-flick 27 Dresses – always the bridesmaid, never the bride, and with the wardrobe (natty blue-and-white stripes in Depor’s case) to prove it. But just like Heigl, their day would come.

You would generously label Donato and Mauro Silva as experienced, while Spurs fans will admit that Noureddine Naybet wasn’t the most consistent centre-back and playmaker Djalminha seldom exerted himself.

But the Spaniards sure could play, particularly their waddling Brazilian, whose skill was nearly as extensive as his post-retirement paunch. Real Madrid and Barça had won 14 of the previous 15 league titles at the start of 1999/00, but under dogmatic Basque boss Javier Irureta the underdogs defied the behemoths, thanks to Augusto Cesar Lendoiro’s mini-Galactico investment. Throw in Juan Carlos Valeron, essentially the Spanish Riquelme, and you’ve got quite the team.

They smashed Real Madrid twice: first, in 2000, with a 5-2 demolition at the Riazor. Then in 2002, facing their foes at the Bernabeu to celebrate 100 years of Copa del Rey finals, Deportivo pooped the biggest of parties. In both seasons, Los Blancos won the Champions League.

And finally… It was all down to basketball. Well, some of it. In that 5-2 Madrid hosing, Djalminha’s rainbow flick over Los Blancos’ defence was inspired by Sacramento Kings point guard Jason Williams’ ‘elbow pass’ from around his back. A thing of pure, arrogant beauty.

Borussia Dortmund (2011-15)

Why you should care: His gurning visage is now a semi-permanent fixture, but it was in Westphalia where the cult of Jurgen Klopp first began converting non-believers. “He’s like a father, friend and brother rolled into one,” said Sky Germany pundit Torben Hoffmann.

It was a slow process – Dortmund were in financial trouble when Klopp took charge – but seeing starlets Mario Gotze, Mats Hummels and Sven Bender establish themselves alongside bargain recruits Shinji Kagawa and Robert Lewandowski was a perfect antidote to the ‘modern football is rubbish’ crowd. Even signing former youth-teamer Marco Reus for big money felt justifiable. Echte Liebe the club call it – ‘Real Love’.

BVB were the genesis of modern gegenpressing, the art of swarming around the opposition to win back the ball immediately after losing it. Klopp called his players ‘Monsters of Mentality’, for their insatiable ability to keep recovering for matches every three days.

With the cheapest season ticket available for £160 and atmosphere created by the Yellow Wall, it didn’t take very long for most of Europe to adopt Dortmund as their second team. Dedicated fans in England even took advantage of cheap flights and became frequent visitors to the Westfalenstadion.

Success – back-to-back Bundesliga titles in 2011 and 2012, plus the 2012 German Cup and a thrilling run to the 2013 Champions League Final at Wembley – was the least they deserved.

And finally... Fan Martin Huschen had Klopp’s face tattooed on his back in 2011. They hadn’t even won the title when the 41-year-old plastics engineer got it done. Dedication.

Wimbledon (1984-88)

Why you should care: It’s easy to adore Barcelona, Ajax, Borussia Dortmund and other hipster teams with all their passing, talent and general bonhomie. Less so a bunch of pyromaniac neanderthals from London, who insist on agricultural football, excessive force and eating sheep’s testicles.

Wimbledon were different. The Dons went from the Fourth Division to the First in four seasons courtesy of a ferocious team spirit and the abilities of former hod carrier Vinnie Jones, ex-Barnardo’s boy John Fashanu and pint-sized scamp Dennis Wise.

In beating Liverpool in the 1988 FA Cup Final – thanks to Lawrie Sanchez’s header and Dave Beasant’s penalty save – the Dons achieved immortality. “The Crazy Gang have beaten the Culture Club,” preened John Motson.

Pretty it wasn’t – “the best way to watch Wimbledon is on Ceefax,” huffed Gary Lineker – but first under Dave Bassett, then Bobby Gould, it wasn’t supposed to be. Newbies would be stripped naked and left to make their own way back through six fields of dog walkers to base. “If you couldn’t handle the pranks and abuse, you were f***ing out,” said future Hollywood ‘actor’ Jones.

And finally… They loved fire. When new signing Eric Young turned up with his Brighton bag in 1987, the squad burned it. Fire was also used to an advantage, with Alan Cork’s car torched so he could plead poverty for a new deal.

New York Cosmos (1975-80)

Why you should care: In 1974, the NASL All-Star Team’s biggest name was former Weymouth defender Dick Hall (four USA caps, four defeats). In 1977, the All-Stars XI featured Franz Beckenbauer, George Best, Gordon Banks and the man who directly or indirectly brought them Stateside: Pele.

It took the Cosmos four years and a recording deal to sign Pele in 1975, having initially hung up his boots at Santos, but he had the desired impact. OK, they won nothing for two seasons, but people watched them win nothing. They epitomised cool: their kit was an instant classic, film stars attended matches and Mick Jagger was a dressing-room regular.

Pele and Beckenbauer notwithstanding, former Lazio striker Giorgio Chinaglia burned brightest. The Italian negotiated a contract by threatening to buy his own franchise, then stayed for eight years, wearing silk robes to post-match interviews and squabbling with the King. When Pele said he wouldn’t pass to a striker who shot from ridiculous areas, Giorgio said, “I am Chinaglia! If I shoot from a place, it’s because Chinaglia can score!”

Although the Cosmos won six regular-season titles on the spin after Pele re-retired in 1977, interest waned. Swagger, not success, made them cult icons.

And finally… When his team faced Fort Lauderdale Strikers en route to their 1977 triumph, Pele didn’t score but everybody else did. An 8-3 rout before a US record attendance of 77,691 featured a masterclass from Beckenbauer and Chinaglia hat-trick, and Gordon Banks wishing he didn’t play for Fort Lauderdale. Bafflingly, the Cosmos still had to win on penalties (the dribbling variety) after drawing the second leg 2-2. You do you, America.

Napoli (1984-91)

Why you should care: Seven years with Diego Maradona brought Napoli their two Serie A titles and only continental trophy. They’d avoided relegation by just a point when he arrived for a world-record £6.9 million fee. It was football’s most transformative transfer, from the moment 75,000 fans watched him land at Stadio San Paolo in a helicopter.

They won a league and cup Double in 1987 and beat Milan to the title in 1990, Diego schooling their famous defence in a 3-0 humbling with a delightful finish and two assists. The Partenopei had a young Ciro Ferrara in defence and appropriately-named Fernando De Napoli in midfield, while Bruno Giordano and a free-scoring Careca formed the Ma-Gi-Ca frontline with Maradona.

If Juventus and both Milan clubs were dull, clean-cut suitors to your sister, Maradona’s Napoli represented the rebel with bad habits. When they clinched that first Scudetto, graffiti in a graveyard proclaimed, ‘Guys, you don’t know what you’re missing’.

And finally… Knowing Diego liked a small line of something spicy at mealtimes, Napoli gave him a rubber, penis-shaped pump to fill with someone else’s clean urine and use in drug tests. In other words: yes, they took the piss.

Bayer Leverkusen (2001-02)

Why you should care: Klaus Topmoller took Bayer Leverkusen to the brink of an unbelievable Treble. Sadly, it was only the brink. After consecutive finishes of 2nd, 3rd, 2nd, 2nd and 4th, including a title lost on goal difference when they couldn’t manage a final-day draw, Leverkusen finished 2001/02 as runners-up in three competitions. Football’s a right sod sometimes.

But it was this near-magical season that crystallised Leverkusen’s cult status. They were competing on three fronts and winning. Ze Roberto was sensational on the wing and Michael Ballack (below) hit 21 non-penalty goals from midfield in the Bundesliga and Champions League, driving into space left by tiny roaming forward Oliver Neuville. Surely this would be the year Leverkusen won their first league title or European Cup?

No. On May 4, Topmoller’s men finished 2nd, having led by five points with three games to go. On May 11, they lost the cup final to Schalke. And on May 15 the horror was complete, Zinedine Zidane’s wonder-volley for Real Madrid confirming the moniker: ‘Neverkusen’.

And finally… A goalkeeper taking penalties improves any side’s cool factor. Hans-Jorg Butt scored three that season.

Dundee United (1982-87)

Why you should care: Name the only side that can boast a 100% win record against Barcelona over more than one fixture. Yep: Dundee United have faced the Blaugrana on four occasions, and won all four. It’s the latter two victories, in the quarter-finals of the 1986/87 UEFA Cup, which Tangerine fans savour most.

Underpinned by the talented up-and-at-em trio of Paul Sturrock, Maurice Malpas and David Narey, United had already reached the semi-finals of the European Cup three years earlier, after winning the Scottish title ahead of Celtic. After a 1-0 first-leg win courtesy of Kevin Gallacher’s second-minute goal – “they wanted it to be over,” boss Jim McLean later said of Barça – the Terrors won 2-1 in Camp Nou despite trailing with five minutes remaining.

Manager McLean was the mastermind. An abrasive character not dissimilar to Brian Clough, the ex-Clyde and Dundee striker used to call his players the night before a game, to prove they weren’t out. “Whatever you’ve heard, multiply it by 10 and you’re not even close,” said midfielder Iain Ferguson.

And finally… After a dominant 2-0 win in the first leg of the 1983/84 European Cup semi-final against Roma, McLean joked: “I hope whatever pills they’re on tonight, we can get more of them,” joked McLean. All hell broke loose, with the Italian press convinced that United were drugs cheats. ‘F**k off McLean’ and ‘Roma hates McLean, he’s a c**t’ read two banners present for the return fixture at the Stadio Olimpico. Roma came up with their own backup plan to combat the ‘drugs cheats’ – they bought referee Michel Vautrot for £50,000 and won 3-0.

Athletic Bilbao (1921-25)

Why you should care: “Con cantera y aficion, no hace falta importacion” is the Basques-only motto by which Athletic Bilbao live – with the youth team and fans, there’s no need for imports. Despite the limitations that rule imposes, they’ve still played in every top-flight Spanish season.

Their most memorable vintage came in the 1920s, before Spain even had a national league system. The nephew of Miguel de Unamuno, one of Spain’s most famous authors at the turn of the 20th century, Rafael ‘Pichichi’ Moreno was a slightly-built scoring machine who always wore a knotted handkerchief on his head. Pichichi’s 83 goals in 89 Athletic appearances secured five Basque titles – plus four Copas del Rey, effectively the biggest prize in Spain – to make him the country’s first football hero.

He died in 1922, aged 29, after contracting typhus. When La Liga was formed seven years later, the choice was obvious as to the name of the prize for top scorer.

And finally... It’s not only the Pichichi trophy which maintains the iconic goal-getter’s legacy. It’s tradition for the captain of every visiting team to San Mames to lay a bouquet of flowers at the base of Pichichi’s bust, which sits at the entrance to the players’ tunnel.

Arsenal (1989)

Why you should care: Yes, Spurs (and probably Liverpool) fans, even you. Football was a corrupt, fetid mess in May 1989. Just six weeks old, the Hillsborough disaster’s dark pall hung over a decade defined by Heysel, the Bradford fire and hooliganism so rife that it gave a Tory government the excuse to cage football fans like the feral cattle they’d privately suspected them of being.

Arsenal travelled to Anfield for the final game of the season – the original clash postponed in the aftermath of Hillsborough – knowing they needed to beat Double chasers Liverpool by two goals to win the First Division they had at one point led by 15 points.

Michael Thomas’s dramatic winner provided a timely reminder of English football’s positives. True, Arsenal weren’t particularly pleasing on the eye – this was peak ‘1-0 to the Arsenal’ of Dixon, Adams, Bould, O’Leary, Winterburn – but football was back on the front pages for the right reasons, the Gunners handing flowers to fans and donating £30,000 to the Hillsborough Disaster Fund. This was the moment English football woke up.

And finally… This side has quite the epitaph: nearly all contemporary football literature. Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch gave the thinking football fan a voice, and proof that beyond the knuckle-drugging wannabe members of Combat 18, supporters wanted the beautiful game to be just that. Maybe that’s the greatest legacy for any team to have.

River Plate (1941-47)

Why you should care: Isaac Newton knew it, so did expert plagiarists Oasis, which isn’t to say Ajax stole the idea of Total Football from the great River Plate team of the 1940s, but the Dutch giants definitely stood on the broad shoulders of their Argentine counterparts.

Nicknamed La Maquina (the Machine) by El Grafico journalist Borocoto, this was an ethereal River vintage at a time when South American football already felt like it was from another planet. Still in the era of the 2-3-5 formation, frontline Juan Carlos Munoz, Jose Manuel Moreno, Adolfo Pedernera, Angel Labruna and Felix Loustau switched their positions with such bewildering regularity – Moreno and Pedernera dropping deep into midfield – that defences were tied in knots.

They lifted 10 major honours and became known as los Caballeros de la Angustia, or Gentlemen of Anxiety. Some claimed it was because of a habit of freezing in cup finals, but Moreno argued that it was “because we could score at any moment. Our opponents knew it”.

“You play against them with the intention of winning,” said Boca Juniors midfielder Ernesto Lazzatti, “but as an admirer of football sometimes I’d rather stay in the stands and watch them play.”

And finally… In 2009, Alfredo Di Stefano – who broke into the River team in 1945 – was asked to name the best player he had ever seen. “Munoz, Moreno, Pedernera, Labruna and Loustau,” he said. “Take your pick from that lot.”

Estudiantes (1967-70)

Why you should care: Much is made of s**thousing royalty Sergio Ramos, but in late-60s Argentina there was a team of knaves who bent football law to their will. Or took a chainsaw to it and dealt with the fallout another time.

Estudiantes won the 1967 Metropolitano, then three consecutive Copa Libertadores titles, but under former Argentina manager Osvaldo Zubeldia they were arch Machiavellian pragmatists – the ends always justified the means. “You don’t arrive at glory through a path of roses,” Zubeldia once huffed.

Midfield engine Carlos Bilardo was his boss’s on-field anti-futbol lieutenant, frequently taping pins to his wrist to jab into opposition ribs at set-pieces. The Rat Stabbers (yes, really) could play, too. Dubbed La Tercera que Mata by the Argentine media (the Kids who Kill), Estudiantes pioneered a high press and could count on Juan Ramon Veron (Juan Sebastian’s dad) to provide the guile.

And finally... Still a practising gynaecologist, Bilardo used his medical contacts to discover that Roberto Perfumo’s wife had recently had a cyst removed, and proceeded to taunt the Racing Club defender incessantly during a match. Eventually, Perfumo kicked Bilardo in the stomach and was sent off. Bilardo and his team-mates also chanted “murderer, murderer” at an Independiente player, after their best friend had been killed in a hunting accident. “The match has to be won – that’s the end of it,” Bilardo once said. Nice bloke.

Boca Juniors (2000-03)

Why you should care: Mind your own business, how about that? Carlos Bianchi doesn’t just look like Larry David, he used to manage like him, too. Obsessed by detail and determined to follow his own path – just like David’s fictionalised version of himself in Curb Your Enthusiasm – Bianchi did what few coaches dare, by abandoning their principles and simply attacking.

Dressed in a kit bordering on the pornographic, his Boca Juniors team at the turn of the 21st century were thrilling. Young tyros Nicolas Burdisso, Walter Samuel and penalty-missing fan Martin Palermo drenched La Bombonera in defensive steel and attacking zeal, but it was hipster wet dream Juan Roman Riquelme who brought naughty thoughts to beardy Shoreditch types.

Given creative carte blanche as a genuine No.10, the schemer shuffled quick-quick-slow like a real enganche, literally meaning a hook, but a move with a pause in Argentine tango similar to a playmaker’s promptings. “Riquelme’s brains,” said football philosopher Jorge Valdano, “save the memory of football for all time.”

Boca bagged back-to-back Copas Libertadores before Riquelme moved to Europe. They then won another in 2003, led by Carlos Tevez, a mongrel to his predecessor’s Mozart.

And finally… In charge for all three of Boca’s Libertadores triumphs, Bianchi has won the South American equivalent of the Champions League more than any other manager. He previously lifted the trophy with Velez Sarsfield in the mid-90s, beating Boca 2-1 at La Bombonera en route to the final against Brazil’s Sao Paulo.

Dynamo Kiev (1985-86)

Why you should care: Football statistics are so ubiquitous that The Times now publishes an alternative Premier League table based on ‘expected goals’. More than any other team, Dynamo Kiev are responsible for such proliferation of numbers. Under one-time plumber Valery Lobanovsky, Dynamo developed a scientific approach to the game in which each player was asked to perform 100 different actions in a match. The next day, a piece of paper would be pinned to the training ground wall revealing everyone’s stats. Anyone not up to scratch would be dropped.

“When I was a player,” explained Lobanovsky, who dreamt up the system in a literal laboratory with his assistant Anatoly Zelentsov, “the coach could say that a player wasn’t in the right place at the right moment, and the player could simply disagree.”

Over three spells spread across 20 years, Lobanovsky lifted 29 trophies, including a dozen league titles. The first stint was the genesis of his genius, the third laden with honours and a prolific strike partnership between Sergei Rebrov and Andriy Shevchenko.

But it was the second which truly secured Dynamo’s cult appeal. Led by Oleg Blokhin and Igor Belanov up top, the team which clinched the 1986 Cup Winners’ Cup in Lyon was the perfect example of Lobanovsky’s cause-and-effect interpretation of football chess. He’s got a lot to answer for.

And finally… Lobanovsky loved playing the autocrat. “But I think…” one player once proffered of a training ground move. Lobanovsky interrupted and hissed, “Don’t think! I do the thinking for you. Play!”

Valencia (1998-2004)

Why you should care: If Valencia and 1999/00 La Liga champions Deportivo La Coruna are remembered fondly, it’s because they represent a different time. After Rafael Benitez left to become Liverpool manager in 2004, the next nine Spanish titles went to Barcelona or Real Madrid.

But Valencia were defined by their unit. In March 2004 they trailed Real’s Galacticos by eight points, but a run of eight wins and two draws crowned them with two games remaining. It began with the Copa del Rey. Claudio Ranieri won Valencia’s first major trophy in 20 years, Claudio Lopez spearheading a goal-hungry side that scored 21 times in seven games, including a 6-0 demolition of Madrid.

Post-Ranieri, Hector Cuper then reached consecutive Champions League finals by making Valencia’s Mestalla home a fortress – in 1999/00, six home matches over two group stages brought four wins to nil and a draw with each of the previous year’s finalists, before Los Che pummelled Lazio 5-2 and Barcelona 4-1 in first legs at home. If they’d hosted either final, instead of Paris and Milan, maybe they’d have won one.

With Cuper, Lopez and influential midfielder Gerard all departing for pastures new, that should have been that. Somehow, though, Benitez guided them to the title in a poor season, with 75 points proving sufficient. A fluke, surely? Yet a couple of years later Los Che were title-winners again, playing less defensive football and lifting the UEFA Cup to boot. They even picked up the Fair Play award. Sometimes nice guys do finish first.

And finally… Since 2000, only Valencia and Diego Simeone’s Atletico Madrid, in 2013/14, have managed to wrestle the title away from Real Madrid and Barcelona.

NOW READ...

Why I hate… football fans who cry about players leaving their club

Quiz! Can you name the 71 players with at least 40 Premier League assists?