From Aubameyang to Coutinho: Why elite clubs are paying a high price for failure in the transfer market

The poor transfer records of elite clubs has led to big stars moving for next to nothing just to reduce wage bills

They went to Barcelona and Sevilla, to Valencia and Villarreal, to Lyon and Marseille. Some of the January window’s most intriguing departures had a common denominator. They did not require a transfer fee. Most were loans, with Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang’s move to Barcelona an exception. But collectively, they may represent a shift in the footballing economy and a threat to the business model of some Premier League giants.

The balance sheet will show they still possess assets that, in theory, they could cash in on. Indeed, Manchester United may not have wanted to sell Anthony Martial, who has been borrowed by Sevilla. Perhaps Tottenham hold out hope that Bryan Gil will return from Valencia to London and realise his potential. But Spurs – or Antonio Conte, anyway – have given up on Tanguy Ndombele and Giovani Lo Celso. They would surely have happily sold them. Instead, they exiled them to Lyon and Villarreal for a few months. And then, unless there is a change of heart, Tottenham are confronted with the same problem of how to dispose of them.

Players who were supposed to be the next Moussa Dembele and Christian Eriksen respectively could instead end up as the next Dele Alli, and not in the sense of scoring regularly from midfield: they may go for far less than they seemed worth. It would long have seemed extraordinary that Tottenham could allow Alli to join another club and not receive a penny. And while a structured deal means they will bank £10 million if he reaches 20 appearances for Everton, Arsenal had to write off all of Aubameyang’s £56 million fee.

It makes him the successor to Mesut Ozil, a previous club record buy who fell out of favour and was in effect released. Arsenal got nothing back for an outlay of almost £100 million, just as they brought nothing in when Sead Kolasinac left this January and Shkodran Mustafi left last year. Tottenham may face a similar scenario with Ndombele and Lo Celso. And while some of the Premier League’s loan army may be better positioned to bolster the funds of their parent clubs because they are in the first half of their careers and on relatively affordable wages, players like Adama Traore and Ainsley Maitland-Niles may be the exceptions to the new norm.

While the Premier League transfer market has proved remarkably resilient, many a European club has seen their budget buffeted by Covid, lockdowns and closed grounds. Dusan Vlahovic and Ferran Torres were the only players signed by Spanish, Italian, French or German clubs for £20 million or more in January. There is a far smaller market for big-money deals. There also seems a greater awareness that elite players can be available without needing to actually buy them. Lo Celso, Ndombele, Martial and Donny van de Beek could be entering the pattern of annual loans more associated with Chelsea misfits like Michy Batshuayi and Tiemoue Bakayoko. Many a continental club might now predicate a transfer strategy on the theory that Premier League clubs with bloated squads may be unable to sell some who have dropped out of the side for meaningful sums. Instead, they can be picked up on the cheap.

It cuts both ways, as Barcelona can testify. Aston Villa were able to borrow Philippe Coutinho because no one would buy him. The short-term move contains an option for a permanent transfer of £33 million. In reality, and however well Coutinho does for Steven Gerrard, no one ever need pay that for the Brazilian again, let alone the £142 million Barcelona forked out.

But those who have spent badly are penalised by the reduction in the number of buyers at big prices; combine a large transfer fee with huge wages and the theory that players will retain value and be sellable seems far less reliable. Only some will and Martial and Aubameyang are examples of purchases who, at various points in their United and Arsenal careers, could have reasonably be described as successes. An accountant may disagree with that interpretation now.

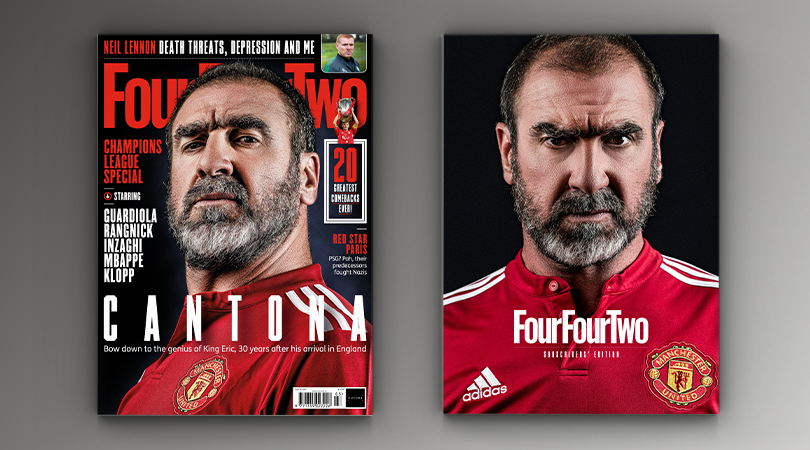

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

It is something that Liverpool and Manchester City, with their higher strike rates in the transfer market, fewer players who are obviously surplus to requirements and the greater continuity in the dugout which means that a new manager is less likely to arrive and want rid of his predecessors’ players, have less need to worry about.

But it underlines a different dynamic that increases the cost of a transfer-market misstep. If Plan A was always for expensive signings to flourish, Plan B was that there was a sizeable pool of purchasers to take them off their hands. Instead, in many cases, it is only with heavy discounts or by borrowing them. The price of failure has just increased.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get three issues for £3.

Restock your kit bag with the best deals for footballers on Amazon right now

ALSO READ

LIST Football Manager 2022: All the FM22 wonderkids you'll need to sign

CANTONA WEEK Eric Cantona week on FourFourTwo: 7 days of King Eric

Richard Jolly also writes for the National, the Guardian, the Observer, the Straits Times, the Independent, Sporting Life, Football 365 and the Blizzard. He has written for the FourFourTwo website since 2018 and for the magazine in the 1990s and the 2020s, but not in between. He has covered 1500+ games and remembers a disturbing number of the 0-0 draws.