Full Members Cup: the anti-European Cup that nobody wanted

English football's domestic cup competitions are often considered second rate by some, but there's a reason nobody gets misty-eyed about the Zenith Data Systems Cup.

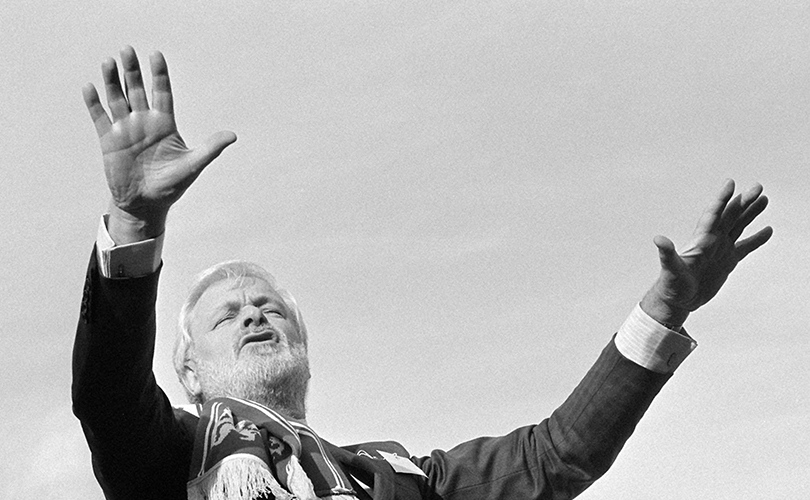

The Zenith System….” Howard Kendall pauses. “The Zenith Systems trophy… Zenith something… what was it again?”

The Zenith Data Systems Cup.

“Bloody hell,” he laughs. “It doesn’t have much of a ring to it? It’s not exactly the Champions League now is it?”

Howard Kendall, who as manager memorably won two league titles, the FA Cup and the European Cup Winners' Cup for Everton in the mid-1980s – but less memorably led the club to the final of the Zenith Data Systems Cup in 1991 – is discussing the strange competitions that came about after English clubs were banned from European football, and is struggling to feign enthusiasm.

- RECOMMENDED Farewell Howard Kendall: A tribute to Everton's most successful manager

The Zenith Data Systems Cup was the last incarnation of what began its strange seven-year life as the Full Members Cup, becoming the Simod Cup for a short time along the way.

Created by the Football League management committee who – chaired by Ken Bates – devised it as a way for the clubs in the top two divisions to play more football, and as a way of getting closer in terms of revenue with those consistently playing in Europe.

More football? In the summer of 1985 that was not an easy sell. During those summer months, football was a national disgrace.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The plan

They thought snooker was a bigger draw

The Heysel disaster was the last tragic act of a tragic six months, and English football had lost its place at the top table of European football. The domestic game had been blighted by trouble on the terraces, while the Bradford fire just three weeks before Heysal spoke volumes about the neglect both stadia and fan safety had suffered.

As a spectacle, there was no clamour to broadcast the game on our television screens. Club chairmen that summer decreed that despite this low point in the game’s fortunes, the £17m on offer for TV rights was too low. The television companies thought otherwise. “They thought snooker was a bigger draw,” recalls the then-secretary of the Football League Graham Kelly.

Maybe they had a point. After all, in April of that year nearly 20 million had tuned in to see Denis Taylor beat Steve Davis at the Crucible. A stand off followed and no games were televised until January 1986.

The numbers watching inside stadiums was just as worrying. “Give us your f***ing money,” cried Bob Geldof that summer as Wembley hosted Live Aid, and the nation did just that. Getting punters to do the same and sound the clicking of the nations’ turnstiles was proving harder.

The 1985/86 season saw just 16.5 million people watch English league football – a colossal drop from a post-war peak of 41.3 million in 1948/49. More football? Are you sure?

Ticking-off

I had been hauled into Downing Street by Margaret Thatcher to explain myself like a naughty schoolboy.

“It was a terrible time to be running the game,” recalls Graham Kelly. “I had been hauled into Downing Street by Margaret Thatcher to explain myself like a naughty schoolboy.

“There were football supporters on her cabinet but none would speak up for the game, and so when Ken Bates came up with the idea of a new competition I was sceptical. Since I had become secretary in 1979 I had argued that we played too much football and wanted the First Division scaled down from 22 clubs.

“Ken argued that that the fans would decide. He was adamant that they would want to watch their teams. He wanted to sweat the players as much as he could.”

Bates was aided in his quest by Crystal Palace’s chairman Ron Noades, who remembers that selling the idea of the new tournament was surprisingly easy – well, to everyone other than the bigger clubs. “The clubs in the lower regions of Division One and those in Division Two were keen for the extra matches,” he noted.

Well not all of them. Twenty-one teams took part in that inaugural campaign, only five of them (Chelsea, Coventry, Manchester City, Oxford and West Brom) from the top flight. Four of the then-Big Five (Liverpool, Everton, Tottenham and Manchester United) had qualified for Europe, but with their passports taken from them by UEFA, would instead compete in something called the Screensport Super Cup (more of which later).

That left just Arsenal, who were invited by Bates and Noades but declined the offer. “They didn’t give us any reason,” recalls Noades. “I guess – like all the other big clubs at the time – they felt it was beneath them. Those big clubs felt they were bigger than something like the Full Members Cup in the same way that they felt they were bigger than everyone when it came to TV contracts.”

Unfortunately the paying public shared that perceived snobbery for the competition. Never afflicted with self-doubt, though, Bates remained bullish. “It is an innovation, just as the League Cup was a little while ago and, no doubt, the FA Cup was back in 1872 – and look how successful these competitions have become,” he wrote in his programme notes prior to Chelsea’s first game in the competition.

The empty swathes of concrete terracing – epitomised by a record low 4,029 at Maine Road that season and a mere 817 at a Charlton tie a year later – said nothing for Bates’s optimism. The format was designed to help. Divided as it was in a north-south basis, there was the hope that more local derbies would bring out more people.

The competition set up a Sheffield derby in the 1989/90 season and drew 30,500 people to Hillsborough, helping to bring the average attendance above the 10,000 mark for the only time in the competition’s seven-year run. Otherwise it lingered at a mere 8,000. Bates’s idea of game changing innovation was hardly taking grip.

That first season though saw Bates – as ever – having the last laugh, with Chelsea winning a thrilling final 5-4 against Manchester City. The absurdness of the competition was embodied by the fact that both teams played Division One fixtures just 24 hours earlier.

“I didn’t mind the Full Members,” recalls Pat Nevin, part of that Chelsea side. “Then again I just loved playing football, so the more the merrier. I remember walking out at Wembley and deciding I was just going to have fun.”

The unloveable cup

How could I get them all going? All I could think was, ‘What are we doing here?’ We should be taking on Europe’s best in Europe’s best stadiums.

Bates could boast of a fine final, then – which was more than the other new tournament held that season could muster.

The Screensport Super Cup (Screensport being a minor TV Channel that would one day become Eurosport), played between the six qualifiers for Europe (Liverpool, Everton, Tottenham, Manchester United, Southampton and Norwich) divided into two groups of three, before a two-legged semi-final and final had also struggled to grasp public imagination, falling foul to – other than sheer apathy – fixture pile-ups.

Liverpool’s semi-final first leg against Norwich had been played in February but due to their league, FA and League Cup responsibilities, they couldn’t get round to the second leg until early May. Oh, the tension.

As for the final against Everton, that wasn’t played until the following autumn, again because of more important fixtures. “Oh yes, the Super Cup,” recalls Howard Kendall. “That was hard.”

Everton as league champions and boasting arguably their finest-ever team had been hit hard by the European ban and for Kendall, trying to motivate his men in the competition was not going to be easy.

“I didn’t bother,” he says. “One night we went to Norwich. They were having new stands built and so we were getting changed in a portacabin. It was wet and dreary outside, the crowd wasn’t much over 10,000 and I’m looking at the likes of Neville Southall, Kevin Ratcliffe, Peter Reid and Graeme Sharp; top, top players. I thought, 'they shouldn’t be here'.

“How could I have given some Churchillian speech? How could I get them all going? All I could think was, ‘What are we doing here?’ We should be taking on Europe’s best in Europe’s best stadiums. They should be running out in front of 70,000 on a balmy continental night and instead, here they are in Norfolk in a portacabin playing for some cup no one even cares about. I felt sorry for them and so my team talk reflected that. All I said was ‘This is a load of old rubbish… out you go’.”

They lost 1-0.

The final was eventually won 7-3 on aggregate by Liverpool, Ian Rush bagging his compulsory cluster of goals against the old enemy, and the striker recalls that the silverware on offer was far from cherished.

“The trophy went missing,” he recalls. “We were handed two cups at Goodison. The home fans had gone but we went over to our lot and a few of the fans had got onto the pitch. I handed one of them the cup I had. That went straight inside his coat and was never seen again. No one ever noticed or asked, though.”

Like the trophy that came with it, that was the end of the Super Cup. For the Full Members (now sponsored by sports shoe manufacturer Simod) life went on, buoyed by the number of teams participating increasing from 30 to 40 (14 in 1986/87 and then 17 in 1987/88 from Division One).

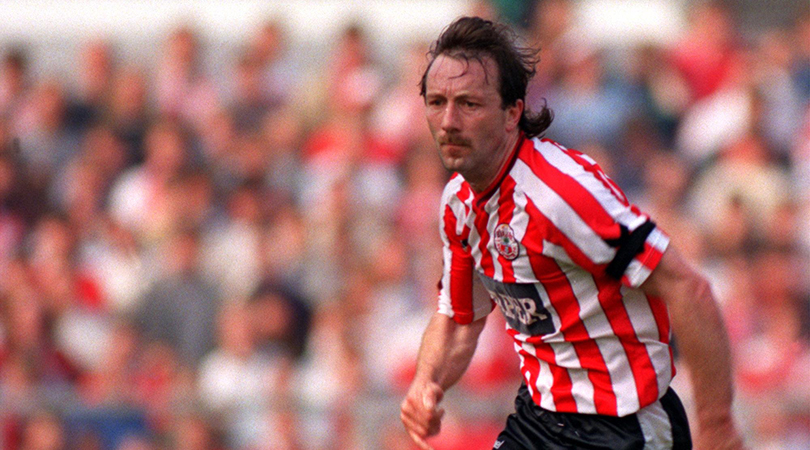

Not that everyone involved was all abuzz. Jimmy Case, winner of three European Cups with Liverpool, couldn’t recall any action once his club Southampton joined in the fun – but he can pinpoint what he was thinking as he put his shinpads on before their first tie.

“'I’ve played against Johan Cruyff, Johan Neeskans and Bertie Vogts' – that’s what I was thinking. You’re professional and you go out and play but it is very hard to focus on. I was lucky. It was those good players who missed out on Europe I felt for. Playing teams from abroad taxes your footballing mind and makes you a better player. The Simod Cup didn’t really ever do that for anyone.”

Tony Cottee, who became the country’s most expensive player in 1988, was one of those players Case felt for. “Am I bitter?” he asks. “Yes I am bit. My opportunities to play in Europe were taken away from me for something I didn’t do. Instead I was taking to the pitch in something called the Simod Cup – I actually did quite well in it – in front of 2,000 people. In the early rounds, you certainly weren’t that bothered.”

A shot at glory for England's lower league clubs

No matter, on the competition went, becoming a straight knockout for extra authenticity and in 1987, even attracting Everton. “They agreed to take part and they were the current champions,” recalls Noades proudly. “A good run in the competition and a trip to Wembley could make a club a bit of money, and the Everton chairman Phil Carter was always great to work with and always very fair to the smaller Division One clubs.

The trophy reached peaked in 1990 when its final between Chelsea and Middlesbrough attracted a bigger crowd (76,369) than the same season’s League Cup showpiece.

“David Dein continued to look down his nose at it and Manchester United... well, they were just Manchester United. What they didn’t seem to realise is they – the super clubs – relied on the rest of us to make the English game what it was.”

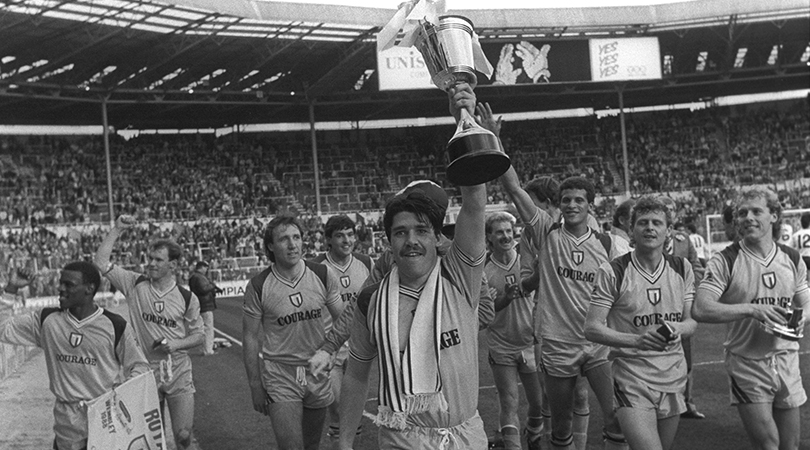

Despite the perceived snobbery surrounding the competition, those clubs in its lower echelons did embrace it and even managed otherwise unlikely glory. Take Reading. Struggling in (and eventually relegated from) Division Two in 1987/88, the club managed to beat a number of top teams from the top flight before conquering Luton at Wembley. Pictures of the day still adorn the Madjeski Stadium walls.

“I get tingles just talking about that day,” recalls then-Royals skipper Martin Hicks. “Going up this famous steps to get the trophy was just incredible. 40,000 of your own fans there to see you do it, a trophy waiting for you and you’re there to lift it. People can call it Mickey Mouse but no one can ever take that moment away from me.

Ron Noades’s club Crystal Palace caught similar cup fever in 1991, beating Everton in the final (it was now under the sponsorship of computer firm Zenith Data Systems) at Wembley. Match of the Day’s roving reporter, comedian and Palace nut Kevin Day smiles fondly when thinking about the competition.

“We’d got the semi-finals in 1989 and got battered by Nottingham Forest at the City Ground,” he says. “We took over 6,000 fans, though, and I mean 6,000 – that’s not the usual supporter's exaggeration. Wembley was a big carrot to us and then having got to the FA Cup final in 1990, here we were again, Charlie Big Potatoes.

“On the run to the FA Cup final a lot of us, including me, had hand puppets made and I was aware that some were scoffing at my decision to bring him back out.

“He was a stripy tiger called Pardew. Some mates thought it wouldn’t be cool to take him again but out he came and there he was under the Twin Towers with me. I used to hold my pint with Pardew’s mouth. I still have him in my loft.”

Day has Pardew the Tiger, Noades has the memories. “I still have the pictures up of that day and to see my Palace side lift a trophy at Wembley remains one of my most cherished days in football,” he says. “I may be biased but because of those sort of memories, I think the competition was a huge success.

“So the big boys didn’t take part and crowds were low at times, but ask the fans, players and managers who went to Wembley when maybe they wouldn’t have otherwise, and they will tell you the same – it was a huge success.”

Noades's enthusiasm isn’t totally misplaced. The trophy reached peaked in 1990 when its final between Chelsea and Middlesbrough attracted a bigger crowd (76,369) than the same season’s League Cup showpiece.

That Sunday was the day the England squad went off and recorded World in Motion with New Order. Tony Dorigo and I were in the squad and were both a bit upset to be missing it

Not that the players were as enamored as the punters. “It was only two years since I’d beaten Liverpool at Wembley with Wimbledon,” recalls the Chelsea keeper Dave Beasant. “I didn’t have much to do (Chelsea won 1-0) and my mind was floating away to the memories of that day.

“As well as that, that Sunday was the day the England squad went off and recorded World in Motion with New Order. Tony Dorigo and I were in the squad and were both a bit upset to be missing it.”

And with that New Order track, times were changing. English football – thanks to Pavarotti’s warbling and Gazza’s weeping – had re-invented itself and was about to usher in a new era of razzmatazz.

“When we won the ZDS, I remember the players – that great team we had at Palace at the time – coming up the steps,” recalls Noades. “Steve Coppell walked past me and whispered, ‘This is the first of many’. I believed him too. But that greed mentality was taking hold, our players left and the Premier League was looming large. There would be no room for a trophy like this one.”

And with the Premier League’s conception and birth, that was that. In 1992, the trophy was laid to rest. An era when even the FA Cup would eventually be deemed Mickey Mouse was upon us and the Full Members – Simod – Zenith Data Systems Cup was history.

Leo Moynihan has been a freelance football writer and author for over 20 years. As well as contributing to FourFourTwo for all of that time, his words have also appeared in The Times, the Sunday Telegraph, the Guardian, Esquire, FHM and the Radio Times. He has written a number of books on football, including ghost projects with the likes of David Beckham and Andrew Cole, while his last two books, The Three Kings and Thou Shall Not Pass have both been recognised by the Sunday Times Sports Book of the Year awards.