Gennaro Gattuso: "He was really breaking my balls so I lost my temper and stuck a fork in his leg"

He made a career from harnessing his inner rage for club and country. But, as the now-Milan manager admits, every now and then ‘the animal inside would come out’ – with dire consequences for anyone in striking distance. Team-mates included…

Illustration: Alexander Wells

The first time I remember someone losing their temper, it was my mother and I was maybe eight or nine. I’d stuck a poster of the Italy midfielder Salvatore Bagni to my bedroom wall. It was an advert – he was wearing the latest line of Dr Martens flip-flops. He was a big hero of mine.

The thing that struck me the most about him was that he always played with his socks rolled down to the ankle, not pulled right up to the knee like all the other players. It may seem like a weird thing for a young boy to focus on, but I loved the fact that he played unprotected with those stocky legs exposed.

My mother said I had to take the poster down. As I tried to remove it, half the paint came off the wall, too. She slapped me.

I do it my way

I don’t ever want to lose at anything, not even a game of cards with my friends. It’s a big part of my character and I’ve always been driven to succeed in everything I do. It’s a part of my DNA, without a doubt. It’s a trait I’d inherited from my father – him and my uncles. Actually, everybody in my family... they’re all the same.

As a player, I had my own way of doing things. I didn’t always follow the advice of others – I played the game my way. I would weigh myself every day and eat the same food every day – white rice and a chicken breast. I didn’t touch a glass of wine or anything other than water for years. I would go running on my own every night.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

I’ve always been driven to succeed in everything I do. It’s a part of my DNA, without a doubt. It’s a trait I’d inherited from everybody in my family... they’re all the same

Before games I was a maniac. I’d be up all night watching television or movies, then I would sleep in the afternoon before kick-off. Maybe that’s why I never had a room-mate, as I was too intense to have one. I actually remember, when Milan played Inter in the Champions League semi-finals in 2003, I had to sleep on the sofa for two weeks beforehand. I was so pumped up.

I’ve recently decided not to play football with my friends any more, because I found myself getting into silly arguments with them all the time. It’s the same with the Milan staff or my former team-mates. I’ll try to avoid competing with them, because when I put on my boots and my jersey, I don’t see the faces of the opposition. And I don’t realise what I’m doing. Then afterwards I think, ‘I did this, I said that,’ and I feel so embarrassed.

So it’s better that I stay out of it, and maybe go for a run on my own instead. Whenever there’s a ball in play, the animal inside me will come out.

Fuel-carriers for goalposts

From the moment I first represented a team on a pitch – when I was 12 – football became the outlet. Until then I’d only been able to play with fuel-carriers from boats as the goalposts – we would play on the beach, surrounded by fishermen, with all the stones and shells under our feet. That definitely added something extra to my game.

It was such a beautiful childhood. I would play at San Siro, Wembley, the Maracana and La Bombonera every day, because we’d named the beaches and streets after the most famous stadiums.

Now priorities have changed. Kids have to stay at school until 5pm because their parents are still working, so they aren’t able to play as much as we did. In the north of Italy it’s even harder to play any street football, and if you don’t sign up for a football school there’s not really very much to do.

But last year, something beautiful happened. I sent Francesco, my 10-year-old son, to Calabria. When he came back six weeks later, he was so pumped up, excitedly telling me all these stories about things he’d done – the same stories I’d lived myself at his age. It was like I’d gone back in time – I couldn’t help but well up.

In times of difficulty, I simply have to shut my eyes and I’m taken all the way back to that time; those beaches, those memories. I lived on the streets until I was 11-and-a-half, not because I didn’t have a family or home but because it was the only way to practise sports and make friends. We had very few possessions – people would work all day for very little money. All us kids could do was go outside, play football and have some fun. We had nothing else, but it didn’t matter. So I guess, as much as anything else, this drive to succeed could be borne out of how little I had when I was a child.

Glasgow was the place where I first started to think like a professional footballer. When I played for Perugia, deep down I thought I lacked the mental strength to go out on the pitch and play without the fear of making a mistake

Blue Ranger

When I was 12 I joined the Perugia academy, where I’d spend the next five years. The first few months there were terrible – I felt really alone, but I suffered in silence because deep down I was convinced it was the right place for me. We won almost every youth tournament we entered and I felt I was improving a lot as a player. I could feel the hunger for success growing every day.

However, this was an era when it wasn’t particularly common for a youngster to play regularly in Serie A. Some of the coaches thought I was special and that I had talent, but I didn’t think of anything other than hard work – running, pedalling, working in the gym and battling to make it in football.

Soon I was being picked for the Italy U18 side. I played in a tournament in France that was attended by scouts from several clubs across Europe. One from Rangers had watched me play and liked what he saw. It wasn’t long before I was on my to Glasgow, aged just 19.

Glasgow was the place where I first started to think like a professional footballer. When I played for Perugia, deep down I thought I lacked the mental strength to go out on the pitch and play without the fear of making a mistake. My legs would be shaking, my emotions getting the better of me. But when I arrived in Scotland, it was all completely different. I understood that I could do this job at a very high level and was lucky to play alongside some great players such as Brian Laudrup, Jonas Thern and Paul Gascoigne.

Even if from a behavioural point of view he wasn’t exemplary all the time, Gascoigne would often offer me advice and really helped me to settle in Glasgow. That’s the thing about Gascoigne; he’s famous for those pranks – for example, he welcomed me to Rangers by doing his business in my socks – but there were also so many kind gestures not many people know about.

Suits me

There was a rule at Rangers, going back to the 1950s, that players needed to turn up for every training session dressed in a suit and tie.

I was a teenager. You’d have been lucky to see me in a jacket even on a Sunday – it just wasn’t my style. So Paul took me to one of the most expensive tailors in Glasgow and told me to pick seven or eight suits. He said the tailor had a deal with the club, meaning the players could choose all the suits they wanted and the money would then be taken in monthly instalments from their wages over the rest of the season. I picked out the suits, the shirts, the ties, and when we went up to the counter it came to about £10,000.

A while later, I discovered there was no deal between the tailor and the club. It was Paul’s way of tricking me into letting him help me out – something he’d just decided to do on his own, without any prompt. He paid for the suits with his own money. This is the Paul Gascoigne not many people know. Now he’s not doing very well. He’s had these problems with alcohol, but we still talk quite often. I will always have these memories of him and make sure that people know about his big heart. He was always thinking outside the box and making the whole dressing room laugh out loud.

I loved my time at Rangers. I loved the passion and intensity of the Old Firm derby. Those were matches that were about so much more than football. For the local players, like Ally McCoist in particular, it was more than a game.

I can remember Walter Smith started talking to me a couple of weeks before one derby. Every day he’d say: ‘Please, Rino, don’t be a beast, don’t get yourself booked too early.’ Then the game kicked off and I was shown a yellow card after about 20 seconds! At half-time I went back to the dressing room, kicked the locker in a rage and ended up with a deep cut over my eye. I wanted to be substituted because I could barely see anything, but Smith told me to be stitched up and get back out on the pitch. That was the way people at Rangers felt about that game.

That’s the thing about Gazza; he’s famous for those pranks – he welcomed me to Rangers by doing his business in my socks – but there were also so many kind gestures that people don't know

When I signed for Rangers, I was wearing a crucifix my mother had given to me, and everyone was staring at me in a really strange way. I kept wondering what the f**k their problem was for them all to be looking at me like that. I was naive. I couldn’t really understand what Protestants vs Catholics meant. I only realised later, but nobody ever told me to remove the crucifix.

To be honest, the biggest complication there was that the manager, Dick Advocaat, wanted to play me at right-back. I didn’t want to play at right-back, which was obviously very frustrating.

An unlikely allegiance

When I was still playing I would never watch the footage back. Never. Now I’ve retired, I’ll see some of the moments when I lost my temper and ask myself, ‘Was that really me? Did I really do that?’ It’s almost like I don’t recognise myself.

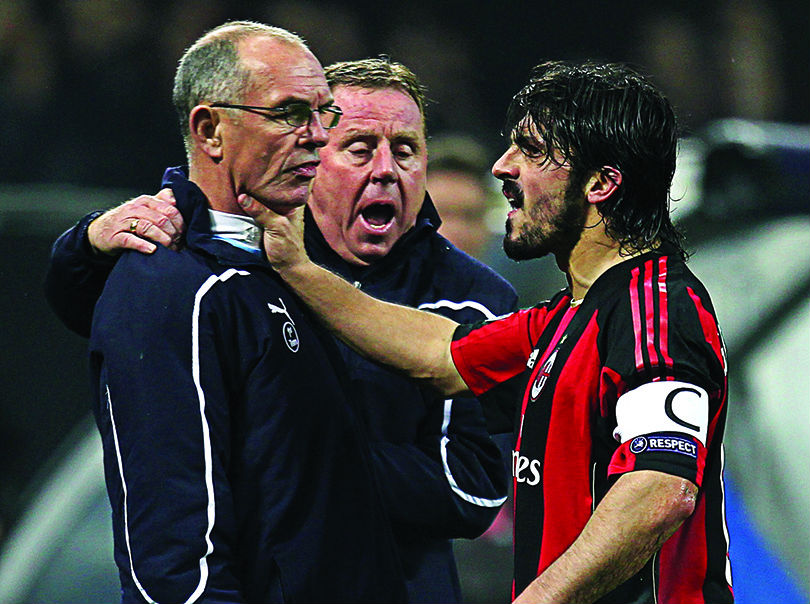

When I see pictures of me with my hand on Joe Jordan’s throat while wearing the Respect armband, I have to laugh, as if I didn’t I’d have to cry. It was an incident that lasted maybe one second, but it was certainly not the right example to set.

It’s the same when I see the pictures of me snarling at Ronaldo, the best player in the world, in a Milan derby. Or Zlatan Ibrahimovic during a game against Ajax. I could go on, but maybe I shouldn’t…

When Ibrahimovic joined Milan, one look between us was enough to clear the air. Just by staring at each other we understood how we both felt about football, which was the same way. We were very different players but our attitude and winning mentality were exactly the same. We understood each other.

As a footballer, you know if someone is setting out to intentionally harm his opponent, or if aggression is just one characteristic of their game. I’ve never walked onto a pitch with the aim of harming another player. I’ve always thought about winning the ball first – going for that ball no matter what. That was my mindset. Always.

When things weren’t going well for me on the pitch, my first thought would usually be how to make things right for Carlo Ancelotti. He was my manager at Milan for many years and like a father to me. You just couldn’t not love him because of his personality; because of how he commanded the dressing room. He’s inimitable, unique. When he talked, he was concise and would hardly ever get angry. The secret to our success was that because we were with Carlo for seven years, we knew each other so well that we were like a family.

A wonderful S.O.B.

One of the great things he did was develop the partnership between myself and Andrea Pirlo. We’d played together for the national team for many years, right through all the various youth sides, but he was a mezzapunta – an attacking midfielder. It was Ancelotti who started to move him deeper so he was playing closer to me. Andrea was out of this world and capable of playing everywhere. Because he had this incredible level of skill and technique, many people forget he could run for an entire day. In athletic terms, Pirlo was a beast. He could run all game without getting tired, although I’m pretty sure I helped to save him a few kilometres, too!

I was very fortunate to play next to him because whenever I was in trouble, all I had to do was give him the ball and, as we say in Italy, he would put it in the bank. It’s clear I would have suffered more without him than he would have done without me.

If you don’t know Andrea, you might think that he is cold, quiet or lacks personality, but trust me, that isn’t him at all. He is a wonderful son of a bitch, always having fun and making plenty of jokes. He was a great team-mate to have around and always an important member of the group. Spending time with him every evening after dinner was a particularly enjoyable experience.

People often ask me about stories in his autobiography. Believe me, he hasn’t written even 10 per cent of what he’s done to me and what I did to him. You can’t imagine the number of slaps I had to give him in the decade or so that I was playing with him. If each slap was worth only one cent, I’d still probably have more than €1 million now.

He’d always try to make me angry, and it’s pretty easy to make me angry. I was always stressed and he was always calm, so we were a decent double act away from the pitch. We’d make the rest of the guys laugh because I would always fall for Andrea’s silly pranks and then react in the inevitable way.

Once, before the Champions League semi-final against Manchester United in 2007, the others were all eating ice-cream, while I was sat eating my white rice. I said: ‘Guys, tomorrow we have a big game so please focus.’ This gives you an idea on how much I cared about diet. Massimo Oddo laughed at me, and said: ‘Come on, we’re just having some gelato, we’re not crazy like you.’

He was really breaking my balls so I lost my temper and stuck a fork in his leg. He knew it was coming as he’d been warned. If you play the funny guy and break my balls, the fork is coming. He kept on and on, so the fork arrived.

There was also a time with the national team, before the 2006 World Cup, at our training centre in Italy. I’d finished training and been to physiotherapy, and while I was there, Pirlo and Daniele De Rossi went to my room and hid in the wardrobe and under the bed. They waited there for three hours until I got back, the idiots. That’s how desperate they were to annoy me. I arrived at around 11pm, ready to go to bed, and they both came bursting out, scaring the s**t out of me. I locked the door and gave them a good beating.

On top of the world

Of course, I have some brilliant memories of my time playing for the national team. My dream as a boy had always been to play for Milan and lift the European Cup, but I’d never dared dream I might one day win the World Cup. Playing in one, maybe, but to actually go and win it? Come on, that was too much.

It took me a long time to really get my head around the fact that we’d won the World Cup. We didn’t realise quite how crazy things were getting back home in Italy before the semi-final against Germany. The enthusiasm was at boiling point. We left the country having been insulted after every training session, then there was all the noise around the Calciopoli scandal… and then suddenly we lifted the World Cup and were national heroes. It was an incredible turnaround.

We owed a lot to Marcello Lippi. We already knew after winning the semi-final that his time as manager would come to an end after that World Cup, whatever happened in the final. He was massacred by the media in the build-up, with his son allegedly involved in the scandal, and it was a time of huge stress for him. So my instinct was to go and celebrate with him, maybe even try to convince him to stay on. That’s why you see the footage of me grabbing him so enthusiastically after we won the final.

I was actually in my underwear by this point because my shorts got caught on the dugout while I watched the penalty shootout and they ripped as I sprinted away to celebrate with my team-mates. So I found myself celebrating in my underwear as, in the moment of the greatest joy of my life, I was still arguing – this time with the substitutes’ bench.

Do I miss playing football? No, not at all. I’ve given more than what I had to the game. I never held anything back. It was my passion and I was willing to give everything I had and more for that passion – I’d have done it for a tenth of what I’ve won.

Once, five minutes into a Milan game against Catania, I tore my knee ligaments really badly. But I kept going. I felt something wasn’t right, but I’d had so many knocks and punches in my life that it just felt like one more. I was willing to do anything for the colours of Milan. I never gave my body a break and I ended up paying the consequences. If you look at my hand, you’ll see it’s not even, not the right shape any more. I was told that I needed an operation on my hand and then spend two months out, but after four days I removed the plaster and carried on playing. For the next two years, every time I went in for a tackle I had to crack my hand back into place.

Looking back on my playing career, the main thing was that I always had lucidity. Each time I made a mistake, I’d apologise and accept the responsibility. That’s a quality I still have, because even now when I’m sat in the dugout as a manager, I live and breathe the game in a very passionate way.

I feel I’ve calmed down a lot, but if someone tells me I have to become a priest, I would say, ‘Sorry, no’ because I like to have that passion. I have to have that passion.

Interview: Martin Mazur

This feature originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!