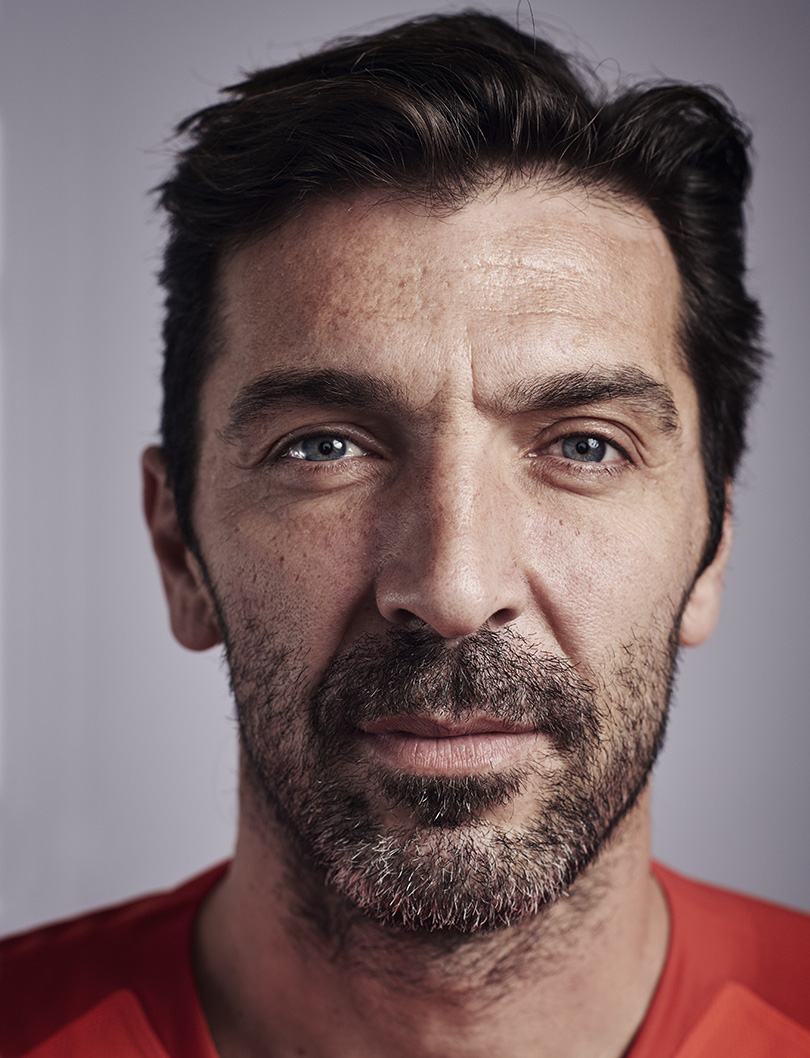

Gianluigi Buffon has a few things to tell you about goalkeeping – and life

The legendary net-minder opens up about the perils of social media, transfer fees and being the last of the ‘proper’ stoppers. Gather round, children...

PGigi Buffon is quite tickled by the prospect of becoming extinct. “Let’s start by saying that soon there won’t be goalkeepers at all,” he suggests, uncorking a bellyful of laughter. “The way football is going right now, I may be one of the last!”

We’re discussing how football has evolved in the long time – almost a quarter of a century – since he made his professional debut. Buffon was 17 years old when he announced himself to the world with a clean sheet in his first ever appearance for Parma, denying Milan and their pair of Ballon d’Or-winning strikers, Roberto Baggio and George Weah. Now 40, and still competing at the highest levels with Paris Saint-Germain, Buffon is uniquely positioned to assess how the goalkeeper’s role has transformed.

He shares his views with FFT now. “Today there is this great – in my opinion, exaggerated – focus on how keepers play the ball with their feet; how they need to pass and move with their other team-mates,” he says. “I myself, ever since I was a kid, was an atypical goalkeeper. I often had this role of being a ‘libero’, playing with my feet a lot. At times, honestly, I did it in an excessive way.

“Despite that, I maintain one thing: if you lose that true attention, that sincere focus on being a good goalkeeper – which means stopping shots, knowing how to come out for a high ball, understanding how you approach a low ball as you come off your line – then, for me, you’re being asked to totally go against your natural role.”

The fun of it

Buffon isn’t discouraging goalkeepers from being adventurous. How could he, knowing where his own football journey began?

As a child he played in midfield and dreamed of scoring goals, instead of preventing them. Then, he watched Thomas N’Kono at the 1990 World Cup and was enraptured by the Cameroon keeper’s eccentricity: the superfluous somersaults and power to punch a ball half the length of the pitch.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Yet the saves, too, were fundamental. Had N’Kono not twice denied Diego Maradona in Cameroon’s tournament opener against Argentina, they couldn’t have earned the shock 1-0 victory that set them up to progress to the knockout stages and become the first African side ever to reach the World Cup quarter-finals.

“You see goalkeepers today who are much better than their peers, but wind up getting overlooked in favour of someone else who can play three tidy passes,” says Buffon. “If you ask me, I would say that every great team – or at least the teams that have won – has always had a great keeper who knows how to make saves first of all. After that, if they can do things with their feet then sure, that is even better.

“And, look: if you don’t care about winning, you can make whatever choices you want. You could even play without a goalkeeper – that’s up to the coach. But if you want to win and claim important trophies, then the role of a keeper, and the fortune of having a great keeper, is still a decisive thing.”

Of course, there are no high-profile managers looking to eliminate goalkeepers altogether. And yet just weeks before we sit here at PSG’s training ground in a north-western suburb of Paris, Thiago Motta, head coach of their under-19 team and Buffon’s former Italy team-mate, gave an interview to La Gazzetta dello Sport in which he defined his preferred formation as a 2-7-2.

“I count the goalkeeper as part of the seven in midfield,” explained Motta, who hung up his boots last May. “For me, the centre-forward is my first defender and the goalkeeper is my first attacker. The team’s play starts from the feet of the goalkeeper. The attackers are the ones who press high to win the ball back.”

Buffon’s response is diplomatic. “This is a vision of football which wants to evolve in a very fast way,” he reflects when Motta’s tactical innovations are put to him. “Already today there are lots of keepers – almost all of them, really – who are integrated into the team in the way they launch play, use their feet and offer support.

“Personally, I think we’ve already seen the keeper’s role stretched as far as it can possibly go. In many different moments during a game, a goalkeeper might be in line with their defenders. So, if you look at it from a tactical perspective, a numbers perspective, then you could say you have another defender [or midfielder] in the starting formation.

“That’s what Thiago was trying to say. You put your keeper into the team’s system of play. But I think that’s already happened.”

The pioneers

Perhaps for a long time. In 1995, the year of Buffon’s Serie A debut, UEFA magazine voted Edwin van der Sar the best goalkeeper in Europe. Working with Frans Hoek, Ajax’s forward-thinking goalkeeping coach, the Dutchman offered a prototype for the ‘sweeper-keeper’ role that’s become ubiquitous over the past decade, stationing himself high up the pitch and assisting defenders in passing the ball out from the back.

Van der Sar later switched to Juventus, before a 23-year-old Buffon was brought in to replace him in 2001. The Italian’s own talent for ball distribution was no doubt considered by the Bianconeri as they agreed to make him the most expensive goalkeeper of all time – a status that would endure for 16 years.

When FFT puts this thought to Buffon, he interrupts us. “Actually, it was 17 years,” he corrects, wagging a finger from across the table and trying to look serious even as the smile fights its way free around the edges of his expression.

Technically, we’re both right. At the time of the 2001 transfer, Italy was still using its own currency: the lira. Juve gave Parma 75 billion of them to sign Buffon, as well as sending Italy international midfielder Jonathan Bachini – valued at a further 30 billion – in part-exchange. That valuation of a combined 105 billion lire was equivalent to about £32.5 million, or €52m, at the time.

When Ederson joined Manchester City from Benfica for £35m in June 2017, it was reported in Britain that Buffon’s record had been broken. However, the pound had weakened considerably against the Euro in the intervening years, meaning this same fee translated to only €40m. To Italians, therefore, and most of the rest of the continent, Buffon remained No.1.

In any case, both players were surpassed one summer later when Liverpool agreed to pay Roma £67m for Brazilian netminder Alisson. But Chelsea, having seen Belgium custodian Thibaut Courtois leave for Real Madrid, then blew all three transfers out of the water by meeting the £71.6m release clause in Spain shot-stopper Kepa Arrizabalaga’s contract at Athletic Bilbao.

The figures don’t matter, though. “In practice, that doesn’t change anything,” says Buffon soothingly, after we’ve talked our way through the currency confusion. Still, his initial interjection tells us that he’s been paying attention to such matters. It’s remarkable that he held onto this record for so long, through an era in which transfer fees have risen far above the rate of inflation.

Because they’re worth it

What changed over the past 18 months? Does the shifting emphasis towards keepers who can play the ball with their feet help to explain enhanced valuations? Or are clubs simply becoming more attuned to the importance of this unique role, at a time when advanced statistics offer closer insight into the difference one player can make?

“I think it’s the latter,” suggests Buffon. “This is a period in which the sums that teams are spending on players have become extraordinary compared to what they used to be.”

A generalisation. Did people not say the same when he joined Juve?

“Yes, yes, definitely. But as clubs get richer and their power to spend increases, we’ve naturally continued down this path. And I think the clubs who made these moves all want the type of player who can be a point of reference for many years into the future as well. In this case, there are two keepers…”

He interrupts himself, raising an apologetic hand while revealing a grin laced gently with mischief. “... OK, let’s put Ederson in there as well and call it three. Ederson, Kepa and Alisson – all three of them are very young, just as I was young when I went to Juventus. So, they assure their new club of this long period of time in which they know they won’t need to get another keeper.

“I think of these as very intelligent moves,” he continues. “If we go back to my signing at Juve, the amount of money they spent on me had every critic saying the exact same thing: ‘No, you can’t pay that much money for a goalkeeper.’

“And, you know, it’s right that those conversations happen as well. But in the end, I was at Juventus for 17 years. I think that with me, Juve made one of the best pieces of business in their history. If you look at it now, I doubt anyone could disagree with that. Only with the benefit of hindsight can you give a true judgement on this sort of financial decision.”

Would Buffon sign up to the idea that clubs in general should focus a larger proportion of their budgets on goalkeepers? Historically, we’ve seen forwards and midfielders command greater sums, yet by his own assessment, winning major trophies requires you to have someone special between the sticks.

“No, I think each keeper should be paid according to their value and according to what they know themselves to be worth,” replies Buffon. “There are no battles going on between goalkeepers and defenders, goalkeepers and attackers, goalkeepers and midfielders.

“A goalkeeper, as a professional athlete, knows the context they’re living in and the sentiment that exists around them. They should then manage that situation as best they can, to profit in certain situations and take a step back at other times. It’s as simple as that.”

French fancy

It wasn’t any financial consideration that took Gigi to Paris. He has earned enough money over the course of his long playing career, and was looking forward to retirement before PSG came forward with an intriguing offer last May. Their interest initially caught him by surprise, and challenged the assumptions he’d made about how he’d like to leave the game: as a Juventus player, off the back of a seventh consecutive Serie A title.

Although he isn’t a one-club man in the way that compatriot Francesco Totti was at Roma, Buffon feels a connection to the Old Lady after 17 years that went beyond what is ordinary. He could have walked away, as many others did, when Juventus were relegated as a result of the 2006 Calciopoli scandal. Instead, he won the World Cup that summer and returned to play the following season in Serie B.

His decision was vindicated as Juventus re-established themselves, becoming an even more dominant force domestically than they had ever been before. Only the Champions League eluded Buffon, who has played in three finals but lost them all. His furious remonstrations with referee Michael Oliver (and subsequent red card) as Juve crashed out to Real Madrid last April threatened to serve as an unhappy epilogue.

Yet Buffon insists that, just as his incentive wasn’t a financial one, nor was it the opportunity for one more run at Europe’s premier club competition which persuaded him to go to France.

“I have to say, PSG were very smart about how they approached me,” explains the Tuscany native. “They understood how a person of 40 years old might think.

“When you’re talking to someone who isn’t a kid any more, you don’t make it an economic conversation about money, and you don’t try to lure them in with talk of the things they could win.

“No, they said to me, ‘We need a man, and a player, like you, as you have specific characteristics and we believe you can help us with what we’re trying to build at the club.’

“That’s gratifying to hear. It makes you feel important again. It was what I needed: to understand that even though I’m 40 years old, an ambitious, strong club such as Paris Saint-Germain would want me to give them one or two more years of hard work.

“The only reflection I wanted to make – the thing I took time over – was this: if you’re getting back into the mentality of someone who intends to carry on playing, do you think you can still deliver at a high level for one or two more years? I considered it for a week and decided: yes, I can do that well.

“So, first I let Juventus know what was happening. That seemed to me like the right thing to do, because I have always had a very correct relationship with the club’s president and the directors. And then, with full freedom, I chose this experience in Paris, which up until now has been magnificent for me.”

Father and sons

It’s also been surreal at times. One of Buffon’s PSG team-mates is Timothy Weah, 18-year-old son of George – the great Milan striker whom the goalkeeper thwarted on his famous debut.

“It’s really beautiful – a very singular thing,” says Buffon. “To begin with, as you can imagine, it seemed pretty strange. But when you’re 40, this stuff can happen. I’ve played against Federico Chiesa, son of Enrico, who was my room-mate at Parma, and I came up against Marcus Thuram [a striker at Guingamp] after playing with his father, Lilian, for 10 years.

“With Weah it was a little bit more particular because George was the symbol of that great Milan team I faced on my Parma debut, and therefore the symbol of a match I’ll always carry in my heart. I was 17 years old and playing against Weah, and against [Zvonimir] Boban. They were champions of an enormous level. To think that I, at just 17, made myself respected by people like that gives me satisfaction.”

THERE’S MORE… Buffon's family affair: how many father-son duos has Gigi shared a pitch with?

Note his use of the present tense. Buffon turns 41 later this month, yet he speaks about certain experiences in the game with the same wide-eyed enthusiasm he has always had.

PSG signed him, in part, for his experience; for the knowledge he has acquired over the course of a stellar career, ready to be imparted on the young and talented squad that Les Parisiens have put together. Buffon relishes the responsibility at the Parc des Princes. At the same time, however, the Italy legend refuses to perceive himself as the old man in the dressing room.

“No, it makes me feel younger!” he insists when FFT asks if playing alongside the likes of Weah and Kylian Mbappe – a World Cup winner at only 19 – ever makes him feel the weight of his years.

“If I want to carry on doing this job, with guys who are inevitably younger than me, then my way of thinking has to stay young. I have to relate to them like another young person would.

“Of course, there are moments when a 40-year-old needs to read a situation and say things that have to be said from the perspective of an ‘adult’. But most of the time, if you want to build a rapport with people of that age, you have to be young yourself. If not, it’s time for you to stop playing.”

Buffon admits that this mindset can take him only so far. He isn’t one for video games such as FIFA or Fortnite, though he will play them occasionally with his sons, observing that the games offer “a way, like any other, to create a common language”.

He has long been fascinated by ways in which people communicate. The idea that shared vocabularies facilitate empathy with different groups of people is something Buffon has touched on previously, when discussing his attempts to learn Chinese. Even from his earliest press conferences in Paris, the gloveman sought to express himself to the media in broken French.

It’s complicated

Social media is another thing altogether. The keeper has a presence across all of the usual major platforms, but he believes this is an area in which life has become more complicated for young footballers than it was for him when he was breaking through.

“When you’re a kid,” he says, “you sometimes struggle to manage all of the emotions and the adrenaline, all of this joy you have inside yourself, for the fact of becoming somebody.

“With social media, you only have to write down one thought, take one photo, and you really risk a lot. You need to be fortunate, as well as good, in choosing the right people in your close circle who can act as a cushion and teach you to make as few mistakes as possible.

“In my opinion, it’s right that a person, especially a young person, has the chance to make mistakes. In life, you learn a lot by messing up. But to mess up a little bit less is still better!”

The troubling side of social media, he reflects, is the way in which it makes young people – famous or otherwise – feel almost obliged to put themselves on display.

And yet, in previous interviews, Buffon has spoken about the fierce desire he felt as a teenager to do precisely that. His need to stand out from the crowd was part of his decision to become a goalkeeper, and to then break with tradition by wearing short-sleeved shirts. “Yes, but my way was exclusively focused on myself as a player,” he interjects. “I wanted people to know Buffon the goalkeeper.

“When I was a kid, I understood that I was something exceptional. I perceived it and I heard it from others as well. So I wanted to show people this truth as soon as I could. It was something that I struggled to keep quiet within myself. But when it comes to my private life, I’m a person who has never wanted to publicise anything. I’ve always tried as much as I can to let that pass unobserved.”

He doesn’t think, then, that he would have used social media as his sons do now, had he been given access to such a thing when he was a teenager still finding his way? “Yes, I would have done,” he replies, acknowledging the contradiction with a sigh. “I would have created some incredible disasters.

“When I think back to when I was 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22… even 23 years old – though I think Juventus and the Juve mentality probably changed me a lot – on some level I was uncontainable. I think I was always a good kid, a normal kid, but I also had this exuberance. It was a continuous excess. So I was probably pretty fortunate that I didn’t grow up in the time of social media.”

That thought feels especially poignant in Buffon’s case, because he has spoken eloquently about struggling with depression at one stage of his career. By 2004 he had won two league titles with Juve, as well as a UEFA Cup at Parma, and established himself as Italy’s first-choice goalkeeper. Yet he had also slipped into what he described as a “black hole of the soul” that threatened to overwhelm him.

“From this point of view, social media can be a double-edged sword,” he tells FFT. “Lots of people find a way to exist that gratifies them and makes them happy, by putting themselves on display in this way. So from that point of view, social media can be therapeutic.

“But the other side is that moment when you don’t have the drive to post a photo; when it’s clear that this fake world, this fake notoriety you’ve created for yourself, will eventually get smaller and you will experience mood swings that can have a significant impact on your mental equilibrium. And in the long run, I think these things can create a dependence which, if you don’t follow it, can undermine your mood and so much else.”

Becoming a meme

We’re now straying into broader societal themes. Returning to the experience of footballers specifically, how much are players affected by today’s online chatter?

Goalkeepers, by virtue of their position, are most exposed to the risk of achieving infamy with a blunder that could cost their team. Does it ever cross Buffon’s mind while he’s playing that a mistake could soon become a viral joke?

“I think this is a very subjective thing,” he says. “The awareness that you fill an important role, and that people will talk about you whether things go well or badly, is something you always have as a goalkeeper. But it’s also true that you don’t know until afterwards quite how big the reaction to a particular incident is going to be.

“If you make a mistake in a game that doesn’t matter, the echo will be smaller. If you do a similar thing in an important match, even someone who has lots of experience can struggle to manage this mass of negativity that gets dumped on you.

“That mass has definitely got bigger with social media. I’d liken it to an avalanche – the kind you see with snow on the side of a mountain. It starts off as this tiny little thing, but then the next thing you know, you have something the size of a town crashing down on top of you.”

Buffon isn’t a grumpy old man weighed down by nostalgia for ‘the good old days’. We’ve discussed some footballing evolutions that he dislikes, as well as concerns that he feels for younger players in this social media age, but Gigi also sees plenty that enthuses him every time he takes to the pitch.

“For me, football today is more open-faced,” he reflects. “Whoever is better, whoever has more rage, wins. You see matches in which the highest-quality players, with the most talent, are managing to show us that ability. A few years ago, maybe that was more difficult. With a perfectly precise tactical game plan, you could often cage even a really talented player and make sure they didn’t have that chance.”

You can see how that thesis might have grown out of personal experience. Buffon’s final two Champions League quests with Juve were both ended by Real Madrid thanks to virtuoso displays from a future Bianconeri player, Cristiano Ronaldo – uncontainable even for a side that boasted some of the world’s best defenders and a tremendous tactician in Massimiliano Allegri. This season, at PSG, Buffon has watched the likes of Neymar and Mbappe destroy opponents on a weekly basis.

“When it comes to talent and technique, Neymar is majestic,” he says of the Brazilian. “You can put a man or even two men on him, but in understanding how to get out of situations, he has a mental ability that is quite incredible to see.

“Kylian has different qualities but he always manages to find a trick in the key moment – or he just uses his sprint, strength and dexterity in such a way that if you try to put a man on him, they will have a very hard time keeping up. They’re both great talents, and that’s another reason why I chose to leave Italy and come to Paris: to play alongside some incredible champions.”

Life lessons

When asked if Mbappe has the potential to become the best player on the planet, Buffon diverts into a story from his own youth.

In October 1997 he was called up for a World Cup qualifying play-off away to Russia. Buffon was supposed to just sit on the bench, but he was thrust into action when Gianluca Pagliuca was forced off through injury after half an hour.

Playing in the snow, on his international bow, with his country fighting to avoid a humiliating first World Cup absence since 1958, Buffon put in a strong performance and was beaten only by a Fabio Cannavaro own goal as the Azzurri drew 1-1. They secured their place at France 98 with a 1-0 win in the second leg.

“After the game in Moscow, I did an interview with a young Russian woman,” recalls the keeper. “I was 19 years old and she said, ‘People here are saying you have the potential to be the best in your position since Lev Yashin [the former USSR international who remains the only gloveman ever to win the Ballon d’Or]. How does that make you feel?’

“I had the madness to reply, ‘Hang on a second – who told you Yashin can be better than me?’ That annoyed her – I remember it well. But I still don’t think I made a mistake saying that. I was presumptuous, for sure, but it’s a remark that has a certain logic behind it. How do you ask a 19-year-old, ‘Are you going to be the best, or is someone going to be better than you?’ I’m 19, and have my whole life ahead of me. Let’s see. We can do all of the sums at the end.

“So, for me, Kylian is one of those players who could write the history of football. But there are lots of questions to come, because while you write history with your talent, first you write it with your head, and with the desire to leave an important mark.”

And does it help to be a little bit presumptuous as well? “No, look: in the end, when I think about how I used to behave, I may have seemed presumptuous. But above all, that was a form of self-defence. It was a way of getting myself accepted in a world of grown-ups.

“Even though I was young, I would step up to you as a grown-up and say, ‘I’m better than you all the same.’ I could see that the grown-ups would often be struck by this young person with such self-assurance. I understood very quickly that this was the only way to be considered on a par with them.

“In the football environment back then, if I hadn’t been like that, as a youngster I would have been told, ‘You must stay quiet.’ I couldn’t accept that. So I went there and said, ‘No, I’m the best and I’m going to play.’ I believe that was one of my strengths, which allowed me to become an important goalkeeper right away.”

Has he lived up to his own youthful hyperbole? Will Buffon be remembered as even better than Yashin?

“If you’d put this question to me when I was 17 or 18, but giving me full knowledge of how my career would pan out, I would have said, ‘Definitely, yes.’ Now I’m 40, I would tell you truthfully that it’s not for me to answer. It’s for other people to judge.

“Over the last 10 years, people have often asked me, ‘Are you the best or is he the best?’ I’m not a little kid who needs to say, ‘Yes, I’m the best! Look at me!’ I don’t give a s**t. I go out on the pitch, I’m happy to do my job, often I succeed and I’m aware of that. However, I don’t need to pat myself on the back every time. It’s a thing that, in my opinion, no champion would do.”

Still, he concedes in the same breath that it’s pleasing to know there are other people out there who are prepared to say it for him. Plenty would name Buffon as the greatest gloveman of all time.

Modern greats

A more revealing subject for him to discuss is the matter of which present-day peers he holds in high regard.

“I can’t tell if this is a good moment for goalkeepers or a less good one,” he says. “There are lots I admire, to tell the truth. I don’t know if it’s the very high level of the goalkeepers that makes me feel like that, or if it’s because there is no single keeper who sparks so much emotion that they push the rest of them to one side.

“The names who first come to mind are Alisson, Thibaut Courtois, David de Gea, Manuel Neuer, Jan Oblak, Kepa Arrizabalaga and my team-mate here in Paris, Alphonse Areola.

“I’m almost certainly forgetting some more, too. It’s a moment in which you can find a whole basket of 10 keepers who are really great, including Wojciech Szczesny back at Juventus.”

Buffon’s standard for assessing these players remains the same as it ever was. He doesn’t judge a fellow keeper on their passing ability, nor indeed the capacity to pull off individual eye-catching saves, but on their ability to consistently keep the ball out of the net, concentrate throughout a game and avoid mistakes.

For all of his focus on the fundamentals, though, this is still the man who fell in love with Thomas N’Kono. Buffon eventually even named a son after him. Does a goalkeeper need to be a little bit mad as well?

“I think there is a vein of foolishness running through every keeper,” he replies. “But then there is in every person, in the end. We can say goalkeepers often lack the brakes or inhibitions that keep them from showing off their madness. The goalkeeper has the courage to show their exuberance to the world.”

And what happens to all of that energy when they retire? Relatively few shot-stoppers seem to go into management. “Perhaps they’re waiting for me,” offers Buffon with a guffaw. But behind the laughter, he has plainly given the idea some consideration.

“Speaking for how I feel right now, the idea of becoming a manager and starting over every day with this life isn’t something I find very attractive at all. If I was to think about being the coach of a national team, and therefore being able to construct a project with the right timeframes and develop an improvement project for a national team, that’s something I think I would like.”

For now, he is just eager to carry on playing. Buffon refuses to place a schedule dictating how many more years he will continue between the sticks. He reveals that the endless questions about his impending retirement stripped much of the joy out of his final year in Turin.

The last of the goalkeepers can find amusement in the prospect of his own extinction. That doesn’t mean he wants to set a date for it.

Photos: Shamil Tanna

This feature originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!