Graffiti, laundry and heroes: 1968/69 in 16 unmissable pictures

Shankly, Busby, Revie, players in towels ands the woman who washes Northampton’s kit: Peter Robinson’s camera snapped them all in a classic season

1. Leeds into battle

Ready for battle? Don Revie addresses his assembled Leeds United players ahead of the new season. Since their 1964 promotion as Division Two champions, Leeds had twice finished second in the top flight, as well as losing the 1965 FA Cup final to Liverpool and the 1967 Fairs Cup final to Dinamo Zagreb.

However, victory over Arsenal in the 1968 League Cup final had secured the club’s first senior silverware and evidently boosted self-belief. Leeds soon added the 1967/68 Fairs Cup by beating Ferencvaros, recording clean sheets in both legs of the final for a 1-0 victory – just like the League Cup one over Arsenal.

But after a 66-game season chasing four trophies in 1967/68, Revie had a single aim in mind. As Johnny Giles recalls, "Revie called us all together after a pre-season training session and proclaimed: 'You’re going to win the championship this time, lads, and what's more you’re going to do so without losing a single league match!' We knew the boss was serious, and honestly believed we were quite capable of achieving such a feat."

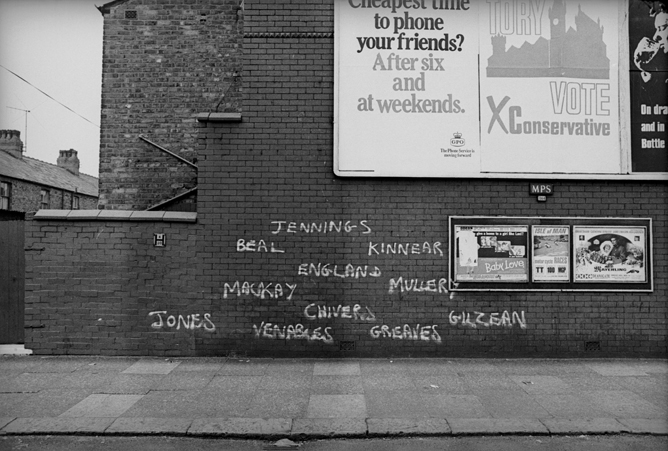

2. Toddo

Graffiti on a wall in Sunderland acclaims the local club’s boy wonder, Colin Todd. Born in Chester-le-Street, County Durham, Todd chose Sunderland over Newcastle and Middlesbrough because the Mackems had a tradition of producing good young players – a decision justified when they won the 1967 FA Youth Cup with a side led by Todd and managed by Brian Clough.

By that time Todd was already a first-team regular at barely 18, a silky centre-back who was calm under pressure and creative in possession. The Black Cats struggled to avoid relegation, though, finally dropping in 1970; the following February, Todd was bought by Derby manager Clough for £175,000 – a British record for a defender. Again, the decision was justified as Todd became a full England international, won the First Division in 1972 and 1975, and was named PFA Player of the Year.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

3. Laundry day

October 1968, and the Northampton Town kit is hung out to dry by one of those behind-the-scenes heroes every club needs. The Cobblers had an up-and-down 1960s – literally: they started the decade in Division Four, rose all the way to the top flight and then all the way back down again.

Promoted under Dave Bowen in 1961, 1963 and 1965, they spent just the one season in the First Division; despite memorable wins over foes like West Ham, Aston Villa, Leeds and Newcastle, they were instantly relegated and fell straight through Division Two, too – at which point Bowen left.

Having avoided relegation to the bottom tier in 1967/68, they had hoped to arrest the slide, but 1968/69 duly delivered a third relegation in four seasons and the Cobblers were once more in the basement.

4. Form a wall

Looking back from an age when graffiti is largely the mindless repetition of tags along railway lines, it’s almost nice to see someone take such care over their daubings. What makes this vandalism interesting – beside the fracturing of the 3-2-5 formation into something resembling a midfield diamond – is that it took place in Manchester: notice the advert for the Omar Sharif tearjerker Mayerling at the Deansgate ABC, while the Odeon went for the R-rated shocker Baby Love. Judging by those films’ release dates, this picture was taken in the dying months of 1968.

Maybe it was put there by a Londoner killing time before the return train from Piccadilly – Spurs lost 3-1 at Old Trafford on 28 August and 4-0 at Maine Road on 12 October, before returning in March for a 1-0 sixth round defeat by eventual FA Cup winners City. Or maybe it was a local who’d decided to support Tottenham – not exactly glory-hunting, considering City were league champions and United European champions.

Either way, it’s a line-up that’s both ephemeral and eternal. Martin Chivers, who would be Spurs’ top scorer for five successive seasons from 1969/70, only moved from Southampton in January 1968; by July, Dave Mackay had been tempted to Derby by Brian Clough and Peter Taylor, while Cliff Jones moved to Fulham in October 1968. But of these 11 players, all bar Chivers and Terry Venables represented Spurs for at least eight seasons – Jennings managed 13.

Next: Clear as mud

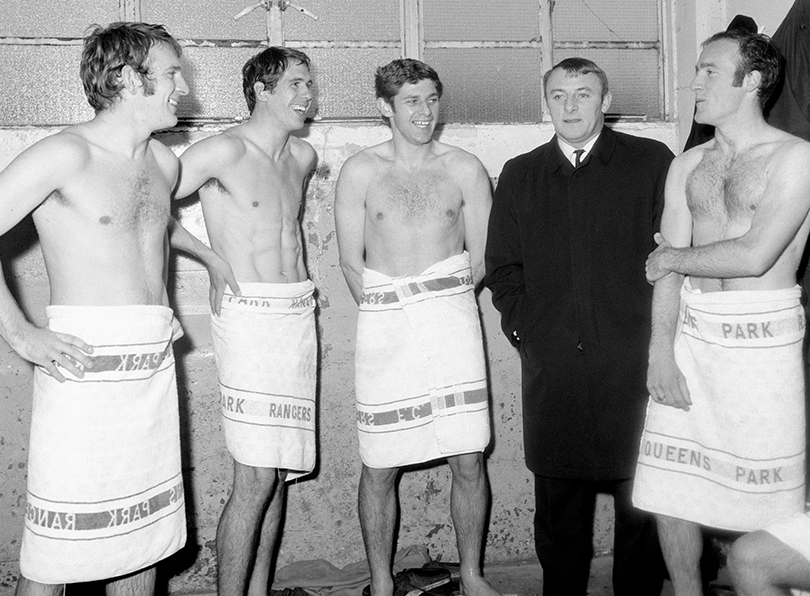

5. Doc Gone

QPR gaffer Tommy Docherty joins his players in the dressing room… but doesn’t take his coat off. As an after-dinner speaker, the Doc would joke that he’d had more clubs than Jack Nicklaus – and during 1968/69 he managed three during a six-week spell.

The Doc had coached Chelsea for six years before leaving in October 1967. He went straight to Rotherham and promptly led them out of Division Two… into Division Three. Leaving Millmoor in late 1968, he was quickly appointed QPR manager but lasted just four weeks before resigning and rapidly turning up at Aston Villa.

In 1967/68 the Rs had been promoted to the top flight under the gentlemanly Alec Stock, who had also led them to the Third Division title and League Cup glory – but chairman Jim Gregory, the archetypal brash car-salesman, eased Stock aside. It didn’t work: they were relegated after just one season.

By then Docherty was long gone, having lasted just four games before quitting. He wanted to sign Rotherham centre-back Brian Tiler, but Gregory didn’t; when the Doc threatened to quit, the chairman thought he was bluffing. He wasn’t, and walked away, joining second-tier Villa in mid-December. Within two weeks he signed Brian Tiler.

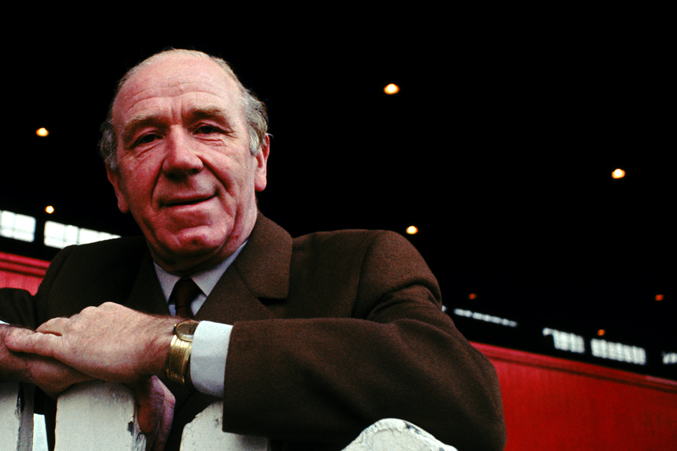

6. The Red Knight

There aren’t many Manchester United legends who played for Liverpool and Manchester City, but Matt Busby ticks all those boxes. He might have even managed Liverpool had the Anfield hierarchy given him the control he wanted over coaching and transfers; they didn’t, United did, and history followed its course.

Busby led United to five league titles and two FA Cups, but it was the crowning glory of winning the 1968 European Cup just after his 59th birthday that earned him a knighthood and led him to ponder retirement – of a sort. On 14 January 1969, Busby announced that at the end of the campaign he would make way for “a younger man… a track-suited manager”, but he would stay on as general manager.

“United is no longer a football club,” explained Busby. “It is an institution. I feel the demands are beyond one human being.” Wilf McGuinness duly donned the tracksuit but lasted just 18 months before poor results prompted Busby to sack him and move back downstairs.

7. Muck and brass at Burnley

More turf at Turf Moor? Burnley winger Ralph Coates considers the effects of the English winter upon the playing surfaces of the First Division. But Coates was unlikely to complain about his working conditions: before a Burnley scout spotted him, he had been an apprentice colliery fitter preparing for life down the County Durham mines.

First Division stalwarts since 1947, Burnley were an interesting club. Under the progressive chairmanship of Bob Lord, they built a bespoke training ground next to Turf Moor and relied on a strong youth production line. Despite not often spending transfer fees, they had finished in the top four on five occasions between 1960 and 1966, before a decidedly odd 1968/69.

They lost 5-0 at West Ham and 7-0 at Spurs, then went on a six-match winning run that included a 5-1 larruping of Leeds - one of only two defeats the Yorkshire side suffered en route to a record-breaking title win. The six-victory run was immediately followed by a seven-match winless streak, featuring a 7-0 hiding at Man City and a vengeful 6-1 loss at Leeds. Later in the season, the Clarets would lose 4-1 at drop-dodgers Coventry and 5-1 at Southampton. In their 42 league matches they scored 55 and conceded 82, a total of 137 goals or 3.2 per game.

Burnley would eventually succumb to relegation in 1971, prompting the sale of Coates – an energetic worker on either flank, and by then an England international – to Spurs, where he would score the winner in the 1973 League Cup Final.

8. Swindon's big day

Swindon Town had never amounted to much, unless you count two FA Cup semi-finals before the Great War and 1964’s 14th-place finish in their first-ever Division Two season (within a year they were relegated again). But from 1961 the new League Cup offered another route to glory for lower-league teams: Rotherham, Norwich and Rochdale each reached early finals, and although the bigger clubs soon started to take it seriously, third-tier QPR won the 1967 final at Wembley.

So Swindon had little to lose when they reached the 1969 final against mighty Arsenal. As Wiltshire prepared for Wembley, photographer Peter Robinson assembled the entire club – managers, players, directors and staff – on the County Ground pitch to mark their first-ever Twin Towers trip.

On the day, Arsenal were flu-ridden and the pitch quickly cut up, but Swindon took their chances. Roger Smart gave them an unlikely first-half lead, and Bobby Gould’s 86th-minute equaliser only set the scene for left-winger Don Rogers to write himself into legend (and reduce the 10-year-old Nick Hornby to tears on the Wembley terraces) with two extra-time goals.

Swindon went on to seal promotion from the Third Division, only losing the title on goal average. They still weren’t allowed into the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup because they weren’t in the top flight, but were awarded the consolation gong of a two-legged face-off with Coppa Italia winners Roma, which they won 5-2 on aggregate; the popularity of these games, along with the World Cup-extended 1970 off-season, prompted the creation of the Anglo-Italian Cup.

Next: Suffering Shanks

9. Stanley knifed

By March 1969, Peel Park was not in a good state. Seven years after financial difficulties had forced Accrington Stanley to resign the Football League, and four years after the club’s ultimate liquidation, the old ground was slowly rotting away.

The unusual suffix Stanley came from the amalgamation of Accrington FC – who themselves had resigned from the Football League over fiscal strife, back in 1893 – with Stanley Villa; the newly-merged entity were founder members of the Third Division North in 1921.

On-field success was scarce to non-existent, and the club was eventually scuppered by a stand. There had been ambitious plans for a new two-tier stand on the Burnley Road side, but instead the club bought a 4,000-seat stand second-hand from the Aldershot Military Tattoo. The £2,000 price mushroomed tenfold via dismantling, transport and reconstruction costs; added to existing debts, the deal effectively took Stanley under.

By the time this picture was taken, Stanley had reformed and would eventually climb back to rejoin the Football League. Although most of the buildings are long gone, the ground is still used by a local school and Peel Park FC.

10. The real Mackay

With Peter Taylor at his shoulder, Brian Clough shakes the hand of Derby captain Dave Mackay – the hand that isn’t holding the Division Two trophy. The managerial twosome had arrived from Hartlepools (then still plural) in summer 1967 and promptly cleared Derby’s decks, retaining just four of the inherited squad: some say Clough even sacked two tea-ladies he heard chuckling after a defeat.

Taylor’s eye for a player and Clough’s man-management would soon turn the club round, and Mackay was the key signing. Approaching 34, he cost just £5,000 from Spurs, a price Clough compared to “getting Laurence Olivier to act in the village hall for thirty bob.” Converted from half-back (midfielder) to a ball-playing centre-back, he helped the Rams romp to the title by seven clear points. Directing operations from the rear, Mackay was sufficiently impressive to be chosen the Football Writers’ Association Footballer of the Year, jointly with Man City’s Tony Book.

Derby’s success story wouldn’t end there. In 1972 Clough and Taylor would lead them to the Division One title; when the pair resigned in late 1973, the Rams turned to Mackay as manager – and he led them to the Division One title again in 1974/75.

11. Ten-bob City

The last FA Cup Final of the 1960s started with a taste of the future. The tossed coin was the new 50p piece, the world’s first seven-sided coin and not even legal tender until October, replacing the ten-bob note as part of preparations for decimalisation in 1971.

Outgoing league champions Manchester City might not have done a good job of defending their title – although better than last time they’d tried it (in 1937/38), when they’d been relegated – but they were at least the firm favourites to win the FA Cup. En route to Wembley they had only let in one goal in six games, and that concession came during a 4-1 win over Blackburn; on the other hand, their opponents Leicester were in the drop zone as a harsh winter led to the league season spilling well into May.

True to form, the favourites kept a clean sheet and won through a single goal from Neil Young, lashed home first-time from 15 yards after good work from Mike Summerbee. Fallowfield-born Young had been his childhood team’s top scorer for two of the previous three seasons – the ones in which City had won the Second Division and then the First Division. And when City won the 1970 Cup Winners’ Cup final, Young scored the first goal and won the penalty for the second.

After Wembley, Leicester turned their attention to the battle against the drop. Their cup run and a harsh winter had left them with five games to collect seven points in order to overtake Coventry, who had already finished their campaign.

Home wins over Spurs and Sunderland either side of a loss at Ipswich left them needing three points from their last two games. Held at Filbert Street by Everton, they then needed to triumph at Manchester United in what was supposed to be Sir Matt Busby’s last league game. David Nish put them in front from the spot but United cruised back to win 3-2, and Leicester were relegated after a 12-year top-flight stint.

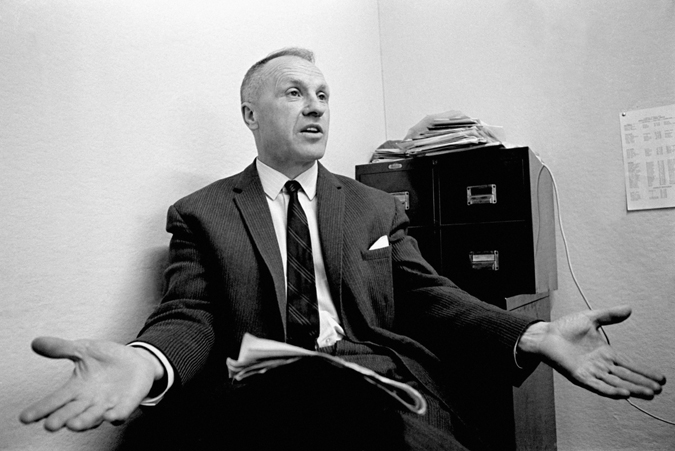

12. Shanks' irksome season

Fingers inky with newsprint, Bill Shankly seems to be cross-questioning an unseen correspondent about something he’s seen in the newspaper. If the Liverpool manager was irked, it was perhaps understandable during the 1968/69 season, which provided a string of annoying disappointments. After League titles in 1964 and 1966 sandwiching an FA Cup win, Shanks suffered a third successive trophyless season – a drought during which his friend and rival Matt Busby had conquered England and then Europe.

Liverpool’s third-place finish in 1967/68 sent them into the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, but they fell at the first hurdle against Atheltic Bilbao: after clawing back a two-goal deficit with two late strikes at Anfield, they lost on the toss of a coin. They went out of the domestic cups to eventual runners-up Arsenal and Leicester, the latter after the Reds had drawn at Filbert Street to take the Foxes back to Anfield, where a Kop-end Tommy Smith penalty was saved by teenage ingenue Peter Shilton.

However, it was a record eighth league title that most agonisingly slipped through Shanks’ fingers. Liverpool hit top spot in October, winning five successive games by scoring 18 without conceding, and were still top on Valentine’s Day.

Don Revie’s Leeds had games in hand, however, and his side had developed a steely inexorability. Breaking several records, the Yorkshiremen gradually eased past Liverpool and rubbed salt in Shankly’s wounds by sealing the title at Anfield with, of course, a hard-fought 0-0. Liverpool ended up collecting enough points and goals to have won the title in any of the previous 11 seasons, but Leeds were the coming power… and another opponent Shanks would have to outwit.

Next: Magpies take flight

13. The brains trust

Don Revie (far right) and his Leeds United backroom staff show off the Football League championship trophy. At the start of the season, Revie had told his players that they would win the title without losing a match. He wasn’t quite right – they lost twice, 3-1 at holders Manchester City and 5-1 at Burnley – but they were unbeaten in the last 28, keeping 24 clean sheets over the 42-game campaign.

Leeds secured the league with a 0-0 draw at title rivals Liverpool and ended up smashing all manner of top-flight records: most points (67 from a possible 84), most home points (39 from a possible 42), most wins (27), most home wins (18) and fewest defeats (2). Even a critic like Mirror journalist Derek Wallis had to admit that “Leeds are the best equipped of all the English teams for the traps, tensions and special demands of the competition they will now enter – the European Cup. Leeds United are the champions, the masters, the new kings of English football – at last.”

The European Cup would elude Leeds but over his remaining five seasons at Elland Road, Revie would cement the club’s place at the very top of the English game with four more trophies; his side would also be runners-up three times in the league and beaten finalists in three major tournaments.

14. Book of the year

Manchester City captain Tony Book reflects on a decent season – although perhaps not quite as decent as the photograph might suggest: technically, City’s ownership of the three trophies was somewhat fleeting as two days after the Maine Road side won the FA Cup, Leeds’ draw at Liverpool sent the league title over the Pennines.

Book had won personal silverware, too, being named joint-winner (with Derby’s Dave Mackay) of the Football Writers’ Association Footballer of the Year award. Both men were in their thirties but whereas Mackay had been at the top for over a decade, Book had undergone a much stranger journey.

Born in Bath but raised in India while his father served in the infantry, the right-back hadn’t even played league football until the age of 30, when he was taken to Plymouth Argyle by his old Bath City boss Malcolm Allison (who advised him to alter his birth certificate lest the club directors take fright).

Allison soon joined Man City as Joe Mercer’s assistant, and in summer 1966 persuaded the boss to buy an unknown right-back who was now almost 32. A year later, he was made captain; a year after that, he was lifting the league title; a year after that, he was posing for this picture. Had he waited another year, he could have added a European trophy – but that’s another story...

15. Busby bows out

Fabio Cudicini protects his goal for Milan as white-clad Manchester United seek to draw level in the European Cup semi-final. Sir Matt Busby’s team had lost 2-0 three weeks earlier at San Siro, a difference diligently defended at Old Trafford by a Rossoneri side including Cudicini (whose son Carlo would play for Milan, Chelsea and Spurs), wily minder Giovanni Trapattoni and creative genius Gianni Rivera.

As Cudicini punches away from Brian Kidd, ready to pounce for the falling ball is Denis Law, who had more reason than most to want the win: he had been injured for the 1968 final win. “When I missed the European Cup final the year before,” he later recalled, “I thought we’d go on and win it again because we were so good”.

Law, though, was nullified by his marker, former Torino team-mate Roberto Rosato, who didn’t let their friendship stop him delivering the odd sly dig in the ribs – leading Law to lose his rag and knock two of Rosato’s teeth out. That wasn’t the end of the controversy: after Bobby Charlton pulled a goal back in the 70th minute, United claimed Law’s shot had been well over the line before being clawed away, but the officials were unmoved.

It wasn’t the only trouble Busby’s side had had with overseas sides that season: their two-legged Intercontinental Cup clash with Estudiantes was hardly conducive to harmonious relations. The first leg in Buenos Aires ended with a 1-0 home win, Nobby Stiles sent off and Charlton requiring stitches in a head wound – and there were more early baths in a violent second leg at Old Trafford. With the visitors protecting an early goal from Juan Ramon Veron (Seba’s dad), a brawl broke out and the ref dismissed George Best and Jose Hugo Medina. Not exactly a peaceful global gathering, then.

Two days after the Milan game, United finished their league campaign with a 3-2 win over Leicester and Busby moved “upstairs” into the role of general manager… although his tracksuit replacement Wilf McGuinness would last just 18 months before the knight was back in charge.

16. Painting the toon

Newcastle United skipper Bobby Moncur shows off the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup trophy, which he had done so much to help them win over two legs.

Eight days after beating Rangers in the semi, Newcastle welcomed crack Hungarian outfit Ujpesti Dozsa to a packed St James’ Park. After a goalless hour, the breakthrough came from a most unlikely source: centre-back Moncur, who hadn’t scored in his previous 100+ games in the six years since his debut. It took him just eight minutes to double his tally, and Jimmy Scott’s third made the second leg a mere formality.

Or was it? Being Newcastle, they almost managed to throw it away, perhaps not helped by manager Joe Harvey suggesting they already had “one hand on the cup”. By half-time in Budapest they were 2-0 down, but Moncur scored soon after the restart, Danish midfielder Preben “Benny” Arentoft added another to level on the night and local lad Alan Foggon made sure shortly after coming on as sub.

Much to Moncur’s chagrin, he remains the last Newcastle captain to lift a major trophy (with due respect to the Texaco, Anglo-Italian and Intertoto Cups). Moncur himself went on to make more than 350 appearances for the club before moving down the road to Sunderland; in 2015 he was appointed to the Newcastle board.

Gary Parkinson is a freelance writer, editor, trainer, muso, singer, actor and coach. He spent 14 years at FourFourTwo as the Global Digital Editor and continues to regularly contribute to the magazine and website, including major features on Euro 96, Subbuteo, Robert Maxwell and the inside story of Liverpool's 1990 title win. He is also a Bolton Wanderers fan.