Guardiola doesn't need centre-backs – and here's why

No stoppers? No problem for Pep Guardiola, whose reaction to a shortage of centre-backs was to invent a new formation, says John Robertson...

This is an article about a German team managed by a Spaniard, but we're going to start in Italy. Paolo Maldini didn't like the idea of tackling.

To tackle, in Maldini's eyes, meant that you'd already made a mistake. He's right, of course: if you defend perfectly, there's no need to tackle at all.

Either you're good to enough to read the play and position yourself to make an interception, or you're good enough to position yourself in a way that discourages opponents from attempting a forward pass at all. In both instances, positioning has prevented a goal. You've not risked committing a foul or being left out of position by attempting a tackle. This form of defence requires an incredible understanding between team-mates. If a single player finds himself out of position, a good team will find the weakness and exploit it. Therefore, such a tactical approach tends to work better with experienced defenders than newcomers.

Trust Pep Guardiola, then, to opt for a back three consisting entirely of full-backs with little to no experience operating in central defensive areas. Placing the emphasis on positioning over tackling for the game againstLeverkusen before the international break, Bayern Munich's enigmatic and experimental manager sought to do away with many of the ideals typically associated with defending and instead focus entirely on intelligent positioning to suffocate the opposition threat. Maldini would have been proud.

Compact vs compact

One of the reasons Leverkusen have been so effective in recent years is the quality of their counter-attack. Roger Schmidt's team prefers to keep a compact shape whenever not in possession, the close grouping of players allowing for both the plugging of defensive holes and – facilitated by excellent passers both down the flanks and centrally – an ability for attackers to peel off in unpredictable directions at the start of the attacking phase.

Unfortunately for Schmidt, Guardiola found a way to use this tendency against him. By playing a back three of David Alaba, Juan Bernat and Philipp Lahm, Guardiola was comfortable when it came to positioning his defence incredibly high up the field when in possession. At times, the entire Bayern team would be well inside the Leverkusen half.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

This constricted the space, forcing Leverkusen to clump together more than usual in their own half. As a result, when Leverkusen gained possession they often found themselves with no forward passing options. Long balls over the top were a possible avenue of attack, but this was made difficult due to the recovery speed of Alaba and Bernat coupled with Manuel Neuer's assuredness in playing the sweeper role.

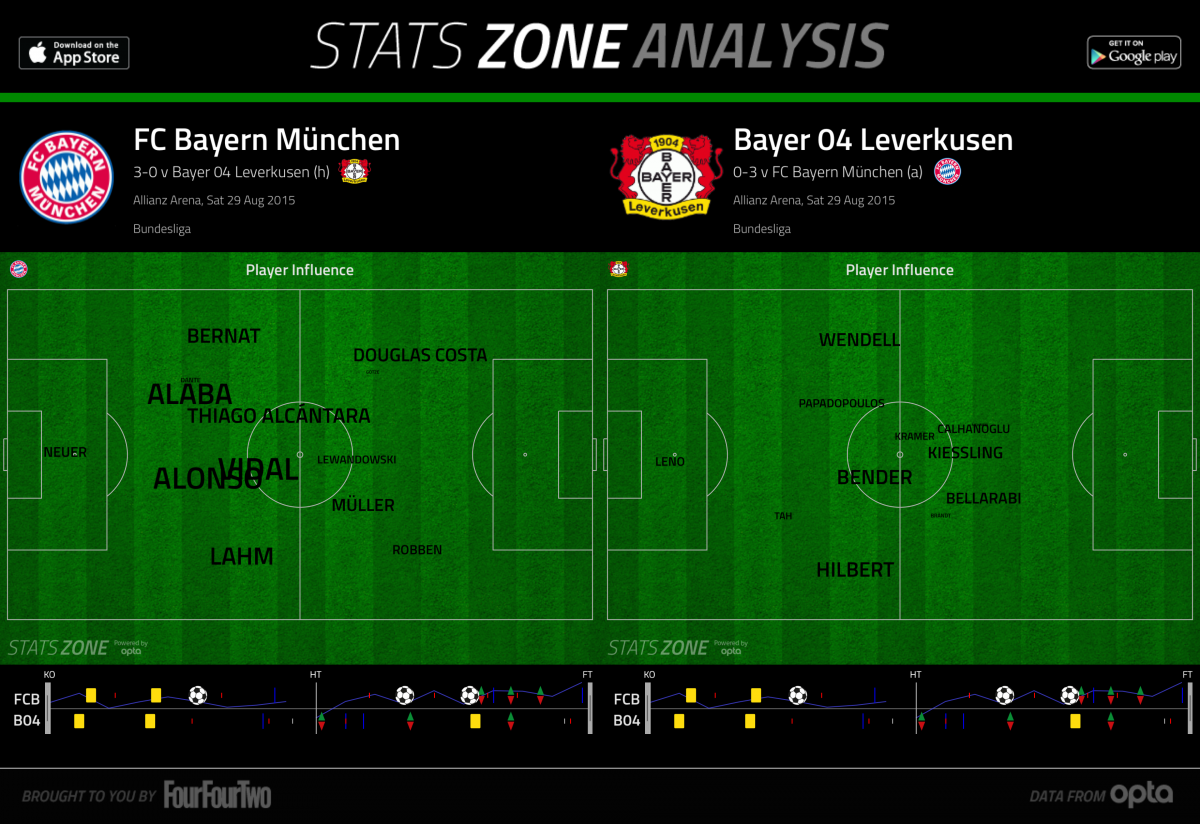

Looking at the average positions of both teams over the course of the 90 minutes reveals just how comically squeezed Leverkusen were, forced to play in a very narrow horizontal cross-section of the pitch.

Leverkusen played completely within confines defined on one side by the attacking threat of Douglas Costa, Arjen Robben & Co., and on the other by the incredibly high defensive line.

The mobile Bayern defence essentially removed one half of the pitch from the game, meaning Leverkusen had little option but to launch hopeful attacks from very deep in an effort to not be caught offside. Unsurprisingly, the visitors created few clear opportunities on goal.

Multi-taskers wanted

Of those Total Football elements to have been adopted by Guardiola, it's the underlying idea that every player on the pitch should be performing more than one role that stands most prominently above the rest. Neuer is not just a goalie, he's also a sweeper. Robert Lewandowski is not only a striker, he's also adept at pulling wide to create gaps between defenders and dropping deep to become a temporary No.10.

Similarly, defenders must perform multiple jobs. The back three against Leverkusen might have been cobbled together thanks to Jerome Boateng's ban and Dante's move to Wolfsburg, but the design of the team provides one of the clearest examples yet of Pep's resolve when it comes to multi-tasking.

As the outer edges of the back three, Bernat and Lahm were expected to move forward to support the more advanced wide players. Perhaps due to age and comparative pace, Bernat took to this role more hungrily than Lahm – the latter relying on Arturo Vidal to assist in the filling in of gaps on the right-hand side.

Through the middle, it was Alaba's secondary job to stay aware of the relative positions of Bernat and Lahm and choose which side to float towards in order to provide defensive cover and a safe passing outlet should moves break down. Alaba's mobility means that a second central defender is not required for this phase of the game, opening up the potential to employ a player in a different position elsewhere.

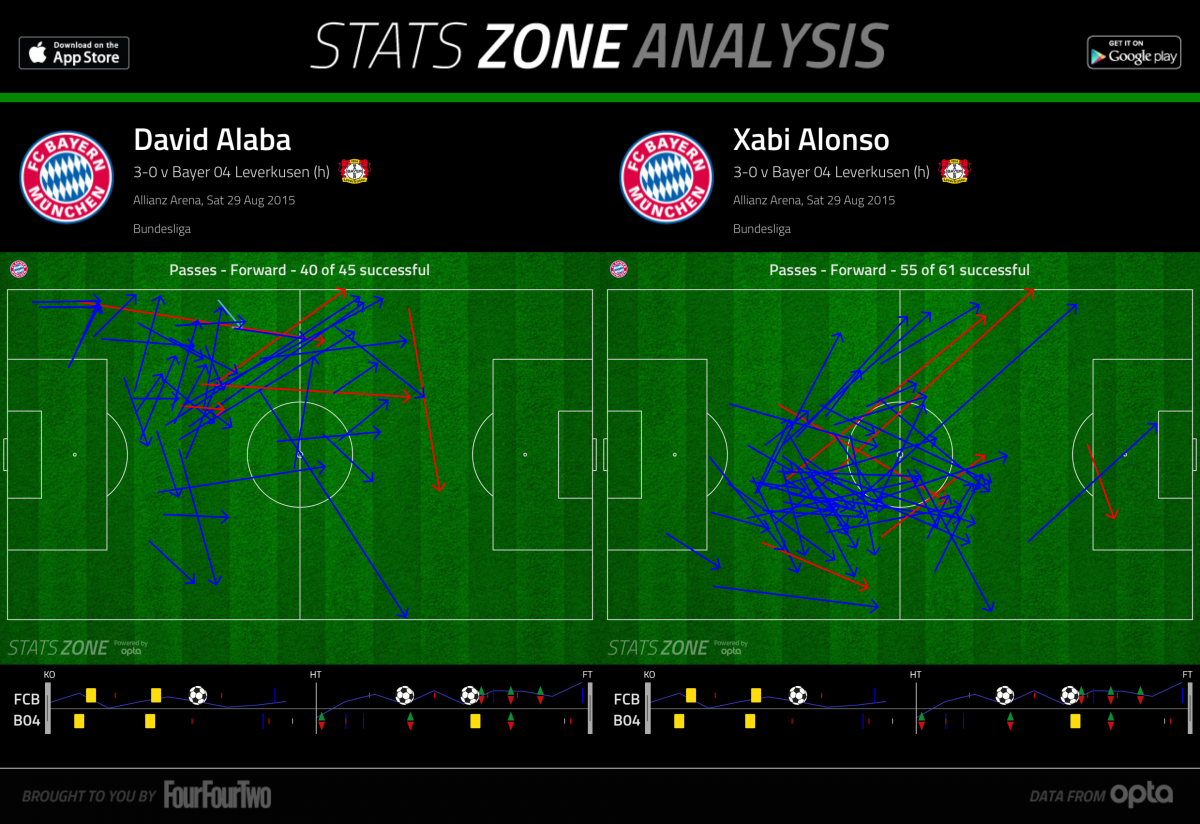

That player was Xabi Alonso, playing ahead of Alaba when Bayern weren't in possession and, frequently, alongside him when they were. As you can see from the passing graphic above, Alaba and Alonso moved the ball forward from the left and right side of central defence, respectively. Alaba's ability to cover the entire pitch laterally gave Alonso free rein to break up the play slightly higher up the field, forming a dual-layered central defence that is capable of starting attacking moves from either side. You could also argue that Vidal and Thiago Alcantara, playing ahead of Alonso, form another line of defence – making it a three-tier system and removing some of the pressure on Alaba to always make the right positional decision.

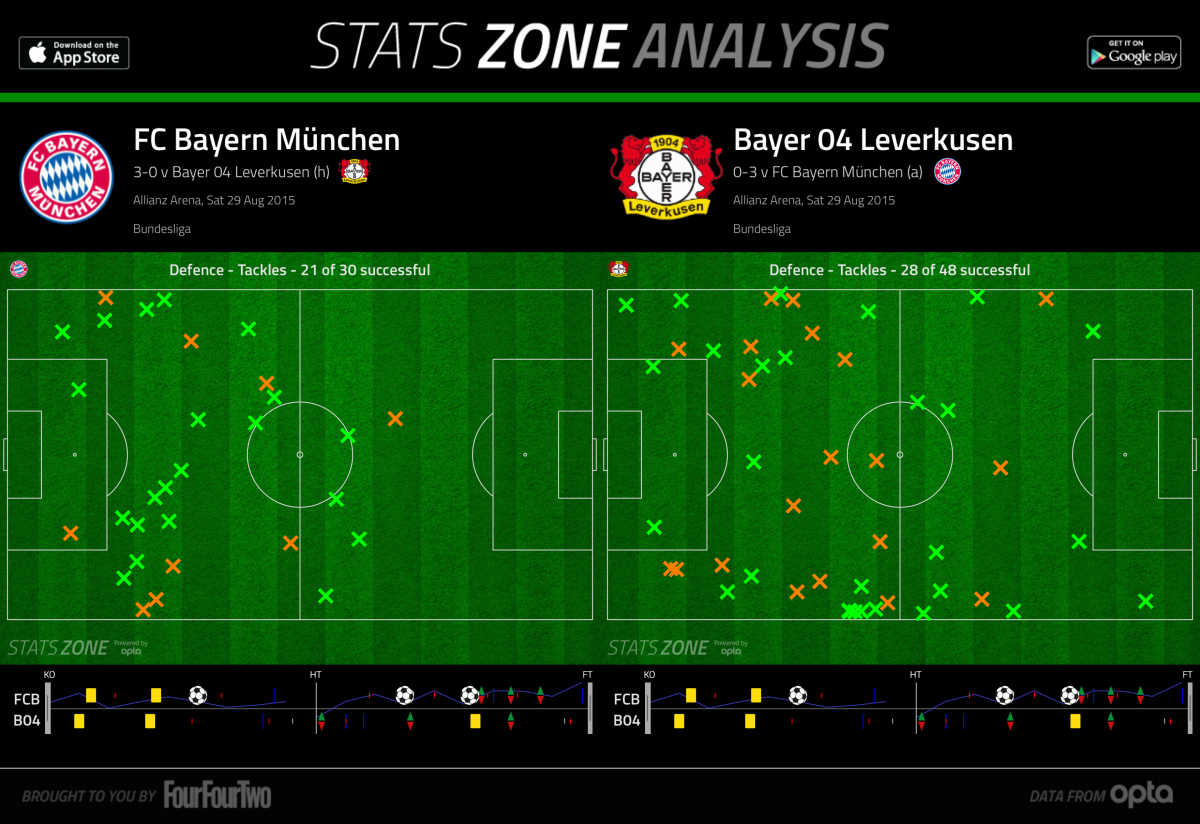

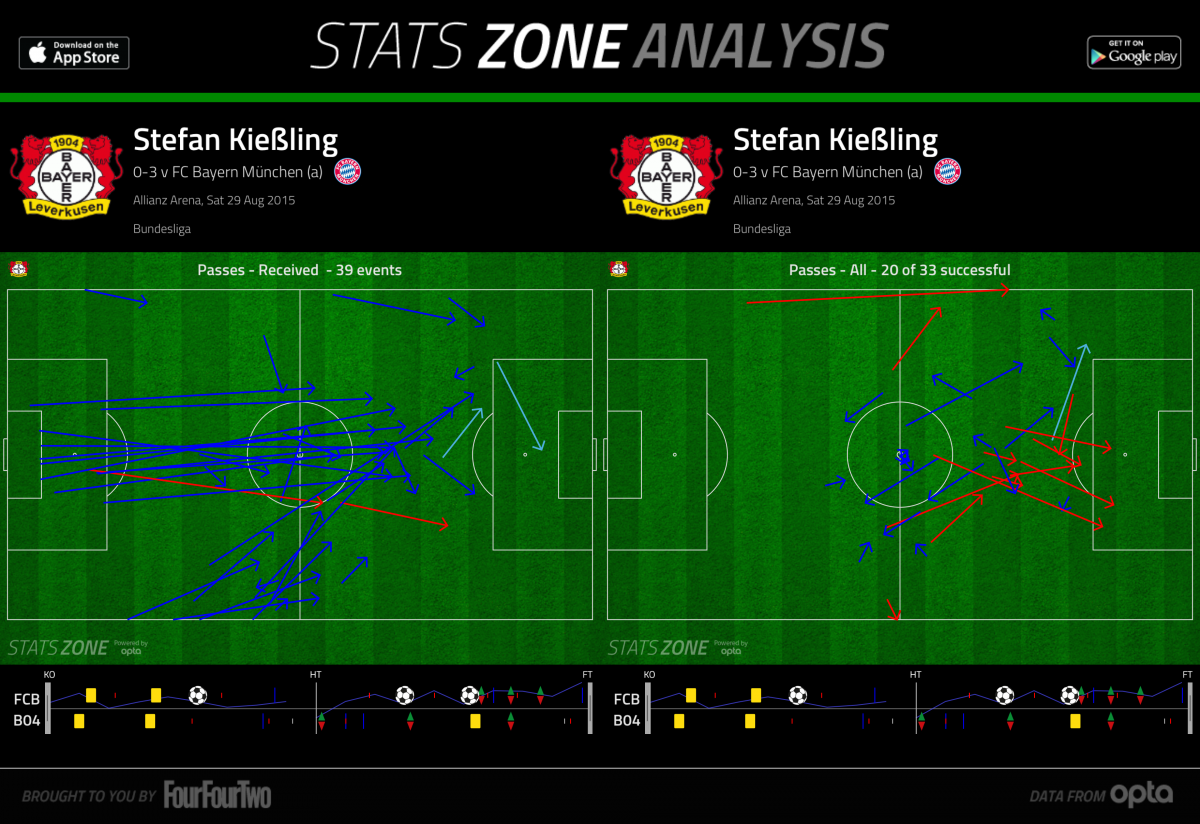

Looking at the areas of the field in which tackles were attempted demonstrates just how disciplined Bayern were in breaking up attacks before they reached the final, Alaba-shaped, wall. By contrast, you can see just how much Leverkusen struggled to contain Bayern's wide players, a threat made possible by Alonso dropping back into defence when needed to cover the advances of Lahm and/or Bernat. Leverkusen weren't above attempting long passes up to Kiessling in order to bypass Bayern's triple-layered defence, but the squeezing effect of Bayern's positioning meant that few targets were consistently advanced enough to pick up the knock-downs and lay-offs. You don't need big, tall, strong defenders when your team is able to position itself so brilliantly as to cut out the danger before the opposition has a chance to get physical.

Future perfect?

In all honesty, Guardiola is unlikely to stick long-term with the same personnel that lined up against Leverkusen. When he has Boateng and Mehdi Benatia to choose from, at least one of them will surely start as a priority. However, that doesn't mean there's nothing to read into here regarding the future evolution of Bayern. Replace Alaba with Boateng and the system would most likely work just as well, only you'd have the added advantage of fielding a player who's an asset when defending corners and set-plays.

Leverkusen's insistence on counter-attacking and playing a compact system resulted in the perfect test bed for Guardiola to try something slightly different with the talented players at his disposal. It remains to be seen whether he is completely sold on the system's merits, and it wouldn't be much of a surprise to him tweak things again against Augsburg on Saturday.

Whatever the case, it's impressive to see a coach reacting to a lack of players by changing the entire gameplan as opposed to simply filling a gap with a partially suitable replacement. It's that kind of mindset that results in the opening of new doors and the progression of football as a whole.

More features every day on FFT.com

STATS ZONE Free on iOS • Free on Android