Henry Norris: The man who moved Arsenal to Highbury – and became Tottenham's first true enemy

Jon Spurling on the controversial figure who took Arsenal to Highbury over a hundred years ago

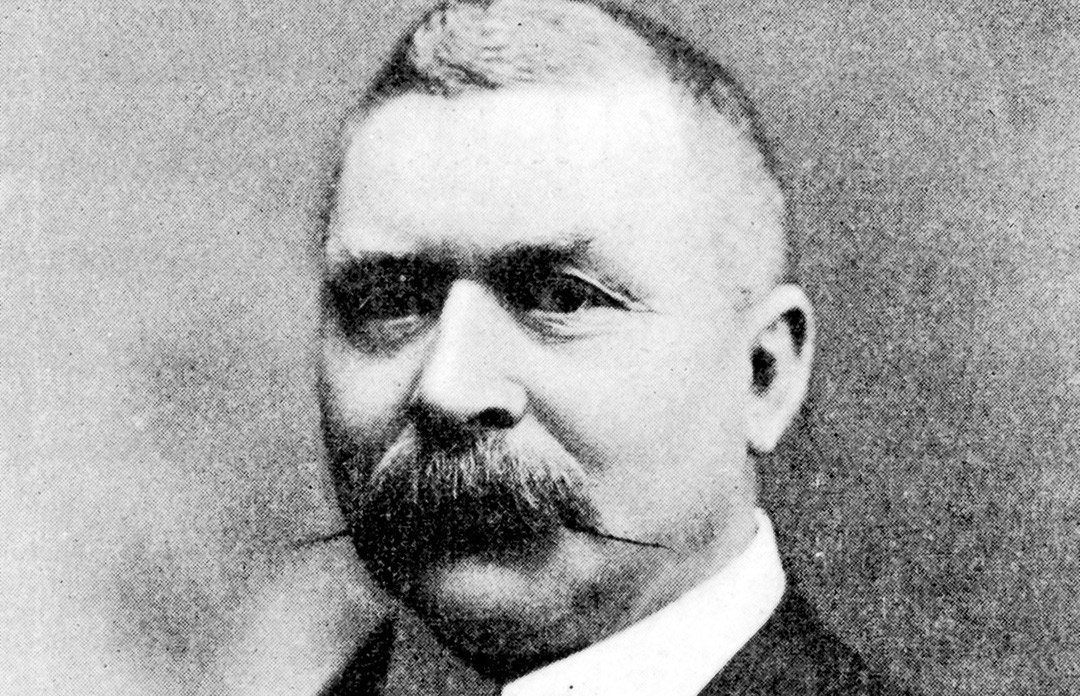

Although Sir Henry Norris died in 1934, his name continues to provoke controversy. Google him and you’ll find dozens of Spurs-related sites citing him as the prime reason to hate Arsenal.

After buying Woolwich Arsenal in 1910, he controlled his club like a medieval fiefdom. In an era when directors and chairmen sat on boards to raise their standing in the community, Norris did things differently. He sprang a variety of questionable fiscal tricks and used bully-boy tactics which made him powerful enemies within the game.

Norris has spawned several imitations, but ‘Deadly’ Doug Ellis, Ken Bates and the late Robert Maxwell have nothing on him. The game’s first ‘Soccer Czar’ has become a creature of myth.

Born in 1865, Norris became a self-made man who had accumulated his fortune through the property market. His company, Allen & Norris, was responsible for transforming Fulham from a semi-rural outpost into an urban jungle.

In the process of constructing, renovating and selling houses, he’d woven a formidable network of contacts in building and banking, many of whom owed him favours. Who’s Who from 1910 lists his interests as ‘wine societies’, ‘dining clubs’ and ‘vintage cars’. Photographs and written accounts suggest that Norris was a terrifying man who bore an uncanny resemblance to Dr Crippen, notorious wife-murderer of the day. Standing at well over six feet, invariably with a pipe stuffed into his mouth, he dwarfed his rivals literally and metaphorically.

He was immaculately turned out in a trench coat, crisply starched white shirt and bowler hat, and would glare demonically through a pince-nez whose lenses were so strong that in board meetings he could discomfit directors by bawling at one while apparently looking at someone else.

One of his rivals in the building trade dared to suggest in the Fulham Chronicle that Norris ran a protection racket in order to preserve the status of his construction company. He retracted the accusation when Norris threatened to let loose his lawyer on him.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And that was just the start.

The Woolwich Arsenal board welcomed Norris with open arms, having heard of his political ‘skills’ when, as director of Fulham, he negotiated their rapid rise through the Southern League right up to Division Two. That this ascent took place in just four years led furious directors of other clubs to suggest that the Football League had received substantial backhanders, but no firm evidence was ever found. Norris was already the undisputed master of covering his tracks.

On buying his majority stake in Woolwich Arsenal, he proposed a merger with Fulham and a permanent move to Craven Cottage to create a London ‘super-club’. He was blocked by the Football League – the only time they stopped him getting his way – but they couldn’t prevent him remaining a director of Fulham while also serving as Arsenal chairman. (The Monopolies and Mergers Commission did not yet exist.)

Foiled in his plan to merge the two clubs, Norris set about rejuvenating the ailing Woolwich Arsenal. In early-1913, Kentish Independent readers were gobsmacked to read the front-page headline: ‘ARSENAL TO MOVE TO THE OTHER SIDE OF LONDON’. In an official statement, Norris pointed out the benefits to the club of moving north to a district with a population of 500,000. The relocated club could tap into the huge reservoir of supporters in Finsbury, Hackney, Islington and Holborn.

Through his contacts in the church, he found that six acres of land at St John’s College of Divinity at Highbury were available. Where better to move than a spot that was only 10 minutes away by tube from London’s West End?

Norris required all his arrogance and political skill to negotiate the minefield of red tape, pressure groups and NIMBYs blocking his path. But he didn’t figure on the furious reaction from Woolwich Arsenal’s hardcore support. Norris claimed that Woolwich people simply did not turn up at games in large enough numbers, but many reckoned he was using dirty tricks.

During a season in which the team was relegated (for the first and only time), they believed he’d deliberately leaked news about the proposed move and under-invested in the team, which he knew would drive down crowds and make the case for relocation stronger. Letters to the local press accused him of selling the club’s soul.

One, sent to the Kentish Gazette, would ring true for Wimbledon fans nearly a century later: “Mr Norris has decided that financial gain is more important than protecting our local club. He is making a mistake. You cannot ‘franchise’ a football club – Woolwich Arsenal must stay near Woolwich. Would Norris advocate moving Liverpool to Manchester? People like him have no place in association football.”

It was alleged that Norris received death threats after proposing the move. But if the reaction from the Woolwich public was hostile, it was tame compared with the lynch mob which awaited him in London. Representatives from Orient, Spurs and Chelsea were quick to protest “in the strongest possible terms” about the move. They were terrified that another London club could erode their fanbases.

The Tottenham Herald described Norris as an "interloper”, and a cartoon portrayed him as being the equivalent of the Hound of the Baskervilles, prowling around farmyards in an enormous spiked collar, ready to rip apart the Tottenham cockerel and steal its food.

An FA enquiry was set up to investigate the whole affair, only for Norris to pack the committee with his buddies and furnish them with some useful facts. Birmingham, with a population of 400,000 and Sheffield with 250,000, housed two top-flight teams each. Why couldn’t an ever-expanding London – population two million – house four?

Unsurprisingly, the committee ruled that the opposition had “no right to interfere”. The Tottenham Herald placed an advertisement begging its readers “not to go and support Norris’s Woolwich interlopers. They have no right to be here.”

The next hurdle to be overcome was the formidable body of Highbury residents, quivering with indignation about the “undesirable elements of professional football” and “a vulgar project” on their doorstep. One resident urged a meeting of Islington Borough Council to “protect the district from what, in my opinion, will be its utter ruin”. But well-versed in local politics, Norris knew the power of the NIMBY brigade. He launched a charm offensive on the group, assuring them that they’d barely notice a football club in their midst, and in any case, that 30,000-plus fans in the district every other Saturday would be excellent for local business.

The final group Norris needed to deal with was the Church of England. Many on the ecclesiastical committee believed football to be ‘ungodly’, and local residents believed that the thought of the Church of England agreeing to a football club buying the land was inconceivable. Norris’s contacts went right to the top, however. After having a £20,000 cheque waved under their noses, the church committee virtually bit his hand off. The Archbishop of Canterbury – an old buddy – personally signed the deed, and Highbury Stadium was built on land where novice priests had once played bowls and tennis.

Five years later, Norris’s dreams of turning Arsenal into a super-club appeared to be in tatters. With the Great War not over by Christmas, no ball had been kicked in anger since 1915, and several promising members of the youth team lay dead in French and Flanders battlefields.

Having pumped a massive £125,000 into the club, Norris apparently faced the ordeal of rebuilding from a mid-table base in Division Two. But he was about to pull off the most audacious – and dodgy – deal in football history.

When the FA reconvened in 1919, Norris had every reason to feel confident. He’d just been knighted for his work as a recruitment officer during the war – he’d managed to assemble three artillery brigades from the Fulham area which played a prominent role in the Battle of the Somme. He was also granted the honorary title of colonel and in the 1918 General Election had been voted Tory MP for Fulham East on a platform of “common decency”, “family values” and “moral strength”. Future Tory Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin described the House of Commons in 1919 as “a lot of hard-faced men who have done well out of the war”. He may well have had the Member for Fulham East specifically in mind.

An FA management committee, anxious to get football back on its feet, proposed that Division One be expanded from 20 to 22 clubs. This wouldn’t seem to benefit Arsenal, who’d finished fifth in Division Two in the 1914/15 season, behind Birmingham and Wolves in third and fourth. It was widely believed that Division One’s relegated clubs, Chelsea and Spurs, would obtain a reprieve.

But Norris got to work on his contacts within the committee, of whom none was more valuable to Norris than his close friend, the committee’s chairman ‘Honest’ John McKenna. (The Liverpool owner had been granted the ironic prefix in light of events during a 1915 match in which four of his team, with his backing, had conspired – in return for cash – to lose a game to Manchester United, so saving United from relegation. Not even McKenna’s considerable influence could prevent the ‘Liverpool Four’ from receiving life bans.)

Norris secretly ‘canvassed’ every single member of the FA committee – bar Spurs directors, who were kept completely in the dark throughout and suspected nothing – with the proposal that Arsenal deserved promotion. Norris informed them that Arsenal had massive potential support – useful in the days when gate receipts were split between clubs – and that Highbury’s proximity to the capital’s delights represented a fun weekend away for provincial clubs and their directors.

Norris also maintained that the Gunners should be rewarded “for their long service to league football”, neglecting to mention that Wolves had actually been league members for longer. As for relegation-threatened Chelsea, Norris palled up with the Stamford Bridge chairman, assuring him his club would be reprieved as long as Arsenal got promotion. Just to sweeten things, according to Arsenal manager Leslie Knighton years later, Norris corresponded with “a few financiers here and there” to guarantee the vote went his way, while noting that Sir Henry’s activities as Arsenal chairman were “merely a bagatelle compared with some of his other business deals”.

When the vote was taken, Chelsea got their reprieve and Arsenal, staggeringly, were promoted – by 18 votes to Spurs’ eight. White Hart Lane was stunned. Even Tottenham’s parrot, presented to the club on the voyage home from their 1908 South American tour, was unable to cope with the news. It dropped dead, thus giving rise to the football cliché “sick as a parrot”.

It was rumoured that McKenna was immediately offered a plush house on the cheap in the Wimbledon area by Norris’s estate agency, but it was never proved – nor were allegations that brown paper bags, stuffed with cash, were handed to other compliant club directors. Norris had once more covered his tracks.

‘Lucky Arsenal’ and ‘Cheating Arsenal’ were two of the more complimentary titles bestowed upon the club at the time, but this was nothing compared to the number of enemies Norris had made, especially down Seven Sisters Road. Norris enjoyed his day of triumph, but his rivals would eventually enjoy theirs.

In 1922, the relationship between Arsenal and Spurs hit a new low. Ever since Norris’s stunt in 1919, officials from both clubs had used the local press to spit bile at each other, with Sir Henry himself happy to join in. As general manager Bob Wall later commented: “The roads and pubs outside Highbury and White Hart Lane could be dangerous places back then. Often the knives were out – quite literally – between fans before and after the match.”

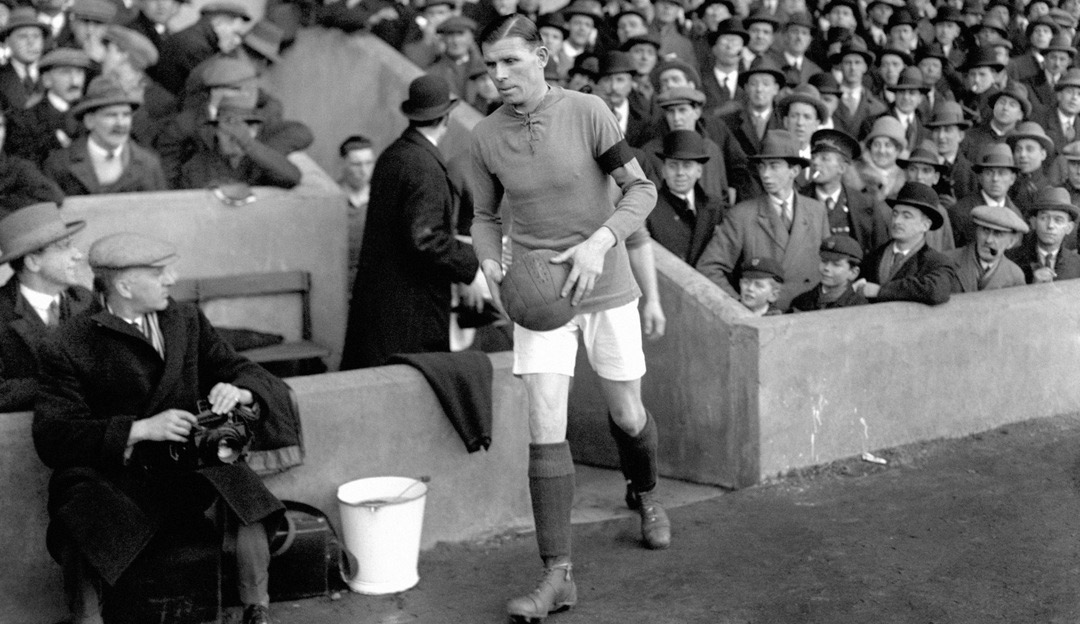

In a disgustingly dirty match at White Hart Lane in September 1922 (Spurs had by then won promotion), the simmering contempt boiled over. Reg Boreham’s double pinched the points for Arsenal in a 2-1 win, but the behaviour of fans and players shocked the tabloid press of that era. Gunners defenders Frank Bradshaw and Arthur Hutchins’ shoulder-charges saw two Spurs players go off injured (there were no substitutes back then); Bradshaw and Hutchins were pelted with missiles from the crowd.

It’s a wonder that the game continued, yet The Sportsman reported: “One could not help feeling impressed by the sledgehammer opposition of the Arsenal.” Here was another example of Spurs artistes being bullied out of it by “grim Arsenal”, according to The Herald. The outraged reporter from the Sunday Evening Telegraph reported that the game contained “the most disgusting scenes I have witnessed on any ground at any time. Players pulled the referee… fists were exchanged.”

In the event, the Commission of Enquiry found Spurs’ Bert Smith guilty of ‘filthy language’, and Arsenal’s Alec Graham of retaliation. Norris left his manager Leslie Knighton to face the music alone, while Norris disappeared to his bolt-hole in the French Riviera, as was his wont whenever a major problem arose.

But his nemesis was closing in.

By 1924, Norris was becoming a desperate man. He’d opted not to stand again as Tory candidate for Fulham East at the General Election after becoming embroiled in a damaging libel case. A rival Conservative MP, Charles Walmer, who took exception to Norris’s support for tariff reform, described him, among other things, as having a “minuscule intellect”.

Sir Henry was furious, maintaining his rival had “slurred my name and character in the most offensive manner possible”. Norris won his case at the High Court, but there was far more to it than met the eye. Like Norris, Walmer was a leading light in the Masons, and was distraught when Sir Henry became Grand Deacon of the Grand Lodge of England, rather than him.

Norris was now among the elite. In his words, he’d “made it”. But being notoriously boastful, he couldn’t resist winding up his fellow MP at every opportunity. Both men sniped at one another in committee meetings, and to the astonishment of onlookers, the pair had to be separated in the corridors of power outside the House of Commons chamber. Walmer eventually snapped, libelling his rival. He came to regret the jibe, as it cost him a small fortune in damages, and he was forced to resign his seat as a result.

Although Norris felt vindicated by his victory, at this point he virtually withdrew from public life, putting all his energies into the Masonic lodge and Arsenal FC. Now in his late sixties, he grew more eccentric by the week, piling further pressure on poor Knighton.

Norris had owned the club for nigh on 15 years, yet still no trophies were forthcoming. Convinced that the team were literally pushovers, he announced in a board meeting that his manager must sign “no more small players. We must have big men.”

Knighton’s unwillingness to abide by this diktat cost him his job. Harold ‘Midget’ Moffatt, an impish winger of 5ft 4in, arrived from Workington. Despite Moffatt looking a good prospect, a furious Norris barked at Knighton: “What is that dwarf doing here?” Moffatt quickly disappeared to Everton and Knighton, who was dismissed shortly before he was due a £4,000 bonus, vanished too.

Knighton later claimed that Sir Henry’s eccentricities had cost the club dear, one of his gripes being that he had been forbidden to spend over £1,000 for a player. Indeed, Norris, in his advertisement for a new manager, warned that “those who pay exorbitant fees in players’ transfers need not apply”.

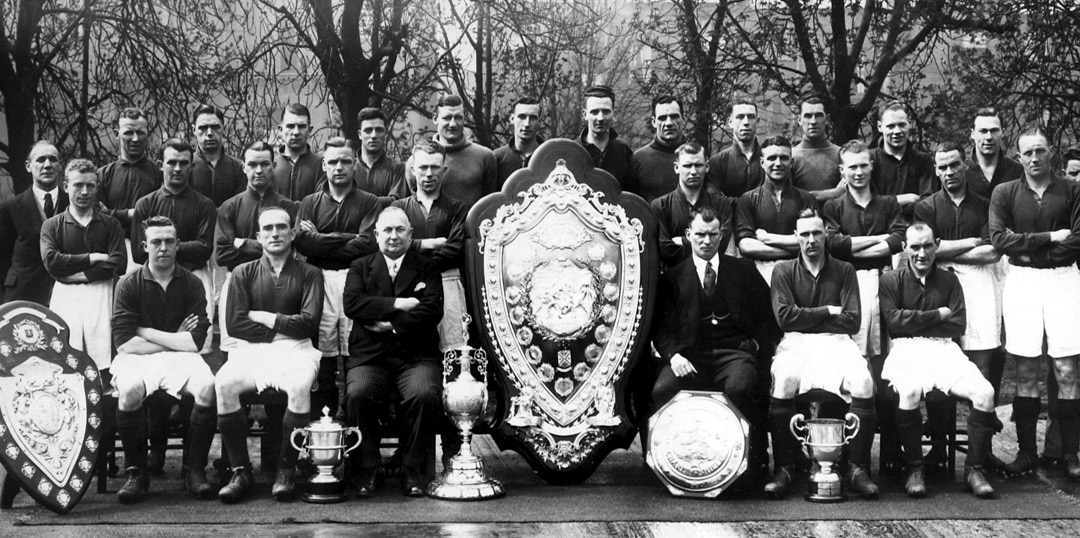

When he appointed Huddersfield Town’s triple Championship-winning boss Herbert Chapman as manager in 1925, Norris finally met his match. The rotund, 5ft 6in Chapman – dubbed ‘Yorkshire’s Napoleon’ by The Examiner newspaper – would in time clash headlong with Arsenal’s czar. Chapman informed Norris that if he really wanted to see Arsenal win a trophy in his lifetime, he’d have to splash the cash: his main target, Sunderland’s brilliant striker Charlie Buchan, was officially worth £5,000. Norris was horrified, but firing Chapman after only a few months wouldn’t be prudent, so he eked out a deal where he would pay £2,000 to Sunderland up front and £100 for every goal Buchan scored during the season.

Buchan came to Highbury, but not before an unexplained, month-long delay in the deal. No one appeared to notice the delay, except for an inquisitive journalist on the Daily Mail who fished around for exclusives and clung to his story for two years. In 1927, the Mail finally ran a series of articles under the headline ‘ SOCCER SENSATION’, alleging that Norris was guilty of making illegal payments to Charlie Buchan. Norris, they claimed, had given under-the-counter sums to Buchan to compensate for the loss of income he would incur from his move south – the player had to give up his business interests and buy an expensive house in London.

The FA was strict about payments made to players, even though everyone in football knew that sweeteners regularly lured players to big clubs. Payments on club houses, cookers, new-fangled washing machines and private schools for the kids were all used to tempt players to move on. But typically, Norris was simply too brazen about the whole thing, virtually shoving Buchan’s money into a brown envelope and handing it over.

Norris had also personally ‘overseen’ the sale of the team bus in 1927 for £125, which somehow found its way into his wife’s bank account. And while it was well known that Sir Henry liked to be chauffeured around London while puffing on a cigar and quaffing brandy, he’d latterly decided to pay for the cost of this through an Arsenal expense account.

The revelations were sensational. Embezzlement? Brown envelopes? How could a high-profile member of the Conservative Party indulge in such financial malpractice? Norris challenged the Daily Mail’s allegations in court two years later, but the charges were upheld by the judge. Norris argued that out of the £125,000-plus he’d pumped into the club, surely he was entitled to recoup £125. And why should he not treat himself to the occasional glass of Courvoisier? As for the illegal payments to Buchan, without them, he said, “we should not have got the player”.

There were even murkier stories doing the rounds. With Spurs fighting relegation in 1928, he was accused of telling the Arsenal team to take it easy against fellow strugglers Portsmouth and Manchester United. Nothing was proved, but an FA committee – convened in response to the Mail’s allegations – believed they finally had enough dirt on Norris anyway. He was banned ‘indefinitely’ from football, and never returned to the game.

With the old tyrant finally out of the way, Chapman was free to break all traditional managerial moulds. The days of club bosses being simply glorified office boys were over. He was fortunate that Samuel Hill-Wood was now the main mover and shaker on the Arsenal board. The Hill-Wood family’s modus operandi, which rang true until grandson Peter reacted to the George Graham affair in 1995, was “why interfere when you’ve got experts to do the job?” No manager had ever wielded as much power as Chapman. He oversaw transfers, administration, and controlled training. His power was virtually absolute. One dictator had replaced another. But this was a more benevolent one.

When Arsenal finally won their major honours under Chapman in the ’30s, Norris could only watch in frustration from the stands. He was proud of their achievements, but without the daily challenge of being Arsenal chairman, he was also a broken man.

He felt increasingly bitter about being labelled as selfish and a bully throughout his business, political and football careers. His lawyer mentioned in the 1928 court case that Norris was a public figure who’d worked unstintingly in order to solve the housing problems of Belgian refugees after World War I.

His QC added that “30 years ago, Colonel Norris deliberately kept the property prices down on his houses, in order that they be affordable for as many of the population of Fulham as possible. This is hardly the behaviour of a self-serving individual. And did not Lord Kitchener personally thank Colonel Norris for his sterling efforts for King and country during the Great War?”

And, indeed, upon his death in 1934 from a massive heart attack, a kinder, gentler Henry Norris could be glimpsed. His estate was valued at £71,000 – the equivalent of over £4m today. Not only were his widow, three daughters and two sisters taken care of, but Norris also looked after many of the Arsenal staff he used to terrify.

Former manager Leslie Knighton was staggered to receive a cheque for £100 from the Norris estate, enabling him to take early retirement. Trainer George Hardy and groundsman Alec Rae received £50 each – over a year’s wages. Rae was likewise dumbfounded, as Norris was “always on to me if the pitch wasn’t quite like the croquet lawn he wanted”.

Norris’s will also rewarded those who’d worked for his building firm and was even rumoured to have bequeathed £500 to the Tory rival he’d sued in 1922, precisely the amount he’d won in damages. As one of his former constituents commented: “Many of his battles seemed serious at the time, but to him they were often simply a form of good sport.”

The Fulham chapel where his funeral took place overflowed with friends and well-wishers. The vicar who conducted the service summed up: “Of the dead, speak nothing but good.”

To this day, the regulars over at Tottenham might beg to differ.

From the May 2004 issue of FourFourTwo. For more see Rebels for the Cause: The Alternative History of Arsenal Football Club, also by Jon Spurling.

QUIZ! Can you name the line-ups for Arsenal 4-4 Tottenham, 2008/09?

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get 5 issues of the world's greatest football magazine for £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a pint in London. Cheers!

NOW READ...

ANALYSIS How realistic is a salary cap for clubs in the Football League? We asked an expert…

EXPLAINED How Champions League reforms mean the League Cup risks being scrapped

WATCH Premier League live stream 2019/20: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Jon Spurling is a history and politics teacher in his day job, but has written articles and interviewed footballers for numerous publications at home and abroad over the last 25 years. He is a long-time contributor to FourFourTwo and has authored seven books, including the best-selling Highbury: The Story of Arsenal in N5, and Get It On: How The '70s Rocked Football was published in March 2022.