Hilarious hijinks and hoofball? The real story of Wimbledon's Crazy Gang

Think you know everything about the original Wimbledon's rise to the top? Think again. Basset, Noades, Sanchez and Fairweather tell FFT the inside story...

It’s funny how things work out.

AFC Wimbledon's underdog tale bears all the hallmarks of a unique, triumph-over-adversity potboiler, with a victorious march through the non-league divisions taking them to within swinging distance of the club owners who took away their team in the first place. At first, playing MK Dons was a dream; the reality was all about survival. Now they've managed both, it's onto bigger things – promotion to the third tier is the long-term aim, but first, this weekend's FA Cup repeat of the 1988 Final in which the Dons conquered Liverpool against all odds.

But the truth is, this story isn’t unique at all. In fact, it happened to the very same outfit over 30 years ago: the original Wimbledon achieved a near-identical feat when they were elected to the Football League in 1977.

AFC will have to go some to match the achievements of Wimbledon Mk1. Within nine years of earning election to the Football League, they had charged all the way up to the top flight.

If their arrival in the old First Division was seen as something of a shock, victories against the likes of Liverpool, Tottenham, Manchester United and Aston Villa, culminating in a sixth-place finish – a position worthy of a place in Europe today – and subsequently an FA Cup victory, was the stuff of pure fantasy.

“We were a fairy tale, but our fairy tale was supposed to end with us going straight back down,” says legendary Dons manager Dave ‘Harry’ Bassett. “That didn’t happen and nobody liked the fact that little Wimbledon came up and managed to stay up. By the end of that first season in the top flight, we were like a wasp in the room to the division’s other teams.”

“Our floodlights were crap”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

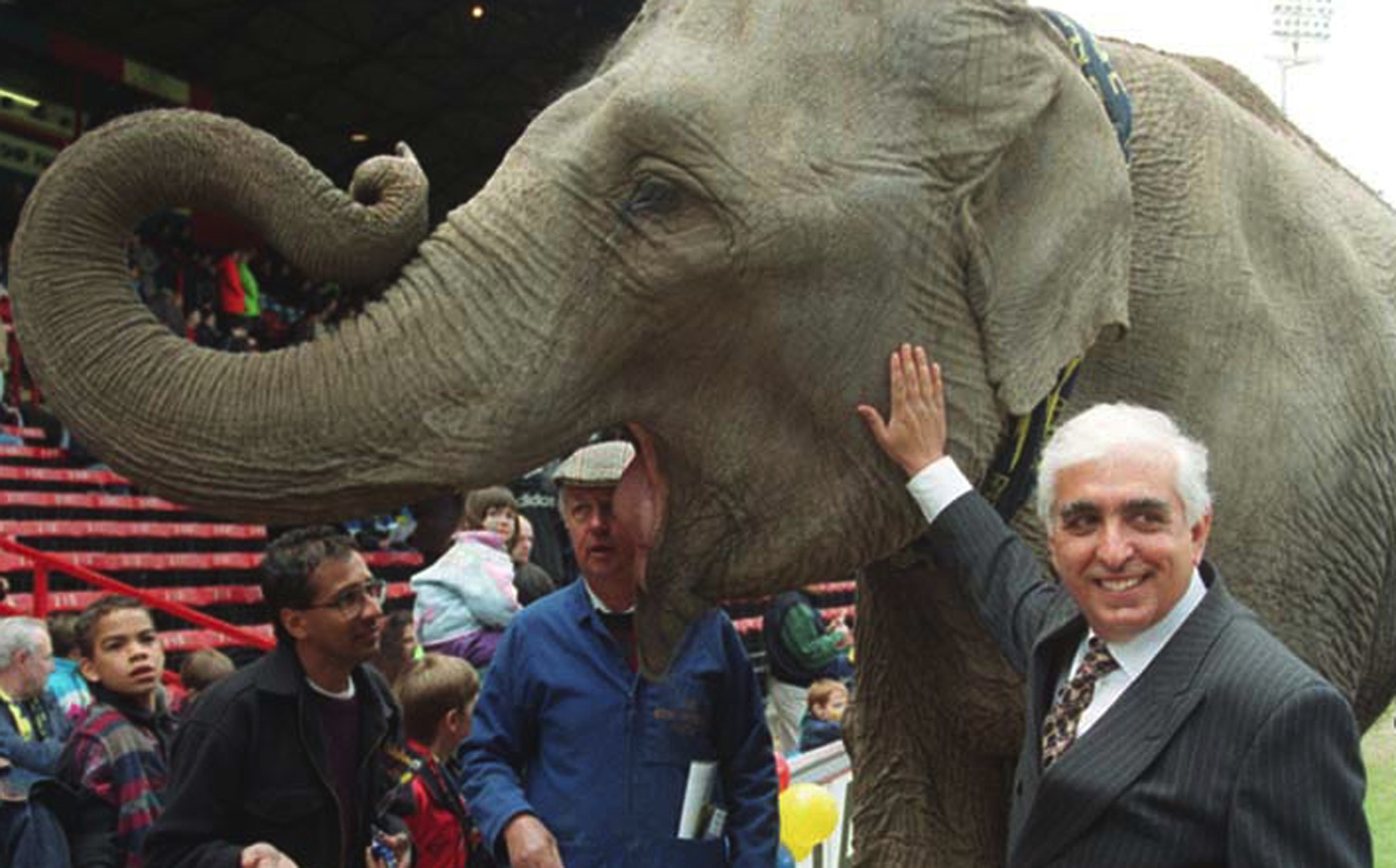

The early blueprints for Wimbledon’s successes were drawn up by former chairman Ron Noades, who would later own Crystal Palace and secure Wimbledon's controversial groundsharing move there when they left Plough Lane in 1991.

Already an amateur team of some repute since forming in 1889, the Dons turned semi-pro in 1964/65 on entering the old Southern League (at non-league’s highest regional tier). They became the first non-league team that century to beat a top-flight club in the FA Cup, when Burnley were dispatched at Turf Moor in the 1974/75 season.

In the next round they drew with champions Leeds at Elland Road before losing the replay. That season, they won the Southern League, retaining it in 1976 and again in 1977. The Dons were banging at the door of the Football League.

However, in the years before automatic promotion, getting elected to the old boys' club wasn’t easy. Wimbledon had to prove they were capable hosts for pro football – which is where Noades’ entrepreneurial skill came in.

“Our floodlights were crap,” he explains. “When we produced a brochure to assist our promotion campaign I put a picture of an evening game in there with the lights on. Underneath I wrote, ‘An evening game at Plough Lane showing the quality of the floodlights’. Everybody read it as meaning they were fantastic when they were awful. There was a lot of kidology involved.”

It worked: Wimbledon were elected and the Crazy Gang was born, though they were soon to experience the first hiccups that arrive with the first flushes of professionalism.

Defender Dave Donaldson, for example, had signed from Walton & Hersham and was on £14 a week; he’d previously supplemented his income with a well-paid job at British Airways. To keep him happy initially, the club – and BA – created a timetable which allowed him to fulfil both roles.

By the time the Dons were preparing to play in the Fourth Division in 1977, everyone in the team was on a full-time contract – everyone, that is, apart from Donaldson. At 36, and with little else to fall back on, he was reluctant to abandon his post-football career. The club kept him on, however, and Donaldson maintained an air of professionalism: if he was ever stuck in London and looking unlikely to make an evening kick-off in some faraway corner of the north, he’d hop on a plane to get there.

But even as they played their first games in Division Four, Noades realised the club would be unable to compete in the transfer market – so he set up a youth development programme. “We didn’t have a lot of money,” he says. “A lot of our team that did so well in the First Division came from our youth system,” says Bassett. “We had an academy before they became fashionable.”

Cardboard boxes, fish batter and nudity

Despite his subsequent standing as Mr Crewe Alexandra, Dario Gradi was the first beneficiary of Noades’ football factory. Made manager in 1978 with Bassett his No.2, he won promotion to Division Three in 1979, followed by immediate relegation. When Noades sold Wimbledon to Lebanese businessman Sam Hammam and took over Palace in 1981, his first move was to swipe Gradi.

This wasn’t the first, or final, controversy to surround Wimbledon and their ownership. Before Noades’ takeover, QPR had discussed buying the club for £15,000 with a view to using it as a nursery team. When Noades moved over to Selhurst there were rumours that the two clubs would merge. “In fact Wimbledon, Palace and Charlton talked about merging,” says Noades, “but nothing came of it. The fans didn’t want it, they were set against it. We did a survey and everyone voted against it.”

With Gradi gone, Bassett took over and began to cultivate a schizophrenic work ethic. Hard graft and lawlessness operated behind the scenes, though this was in evidence before the change in manager: under Gradi’s stewardship the players would regularly sneak into Noades’ office to have sex with girlfriends.

With Bassett in charge, the chaos was cranked up a notch. During training sessions, players were encouraged to run around with their arms in the air shouting, “power!” Practice matches were concluded with a game of rugby-esque ‘Harry Ball’, which on one occasion left a senior player with two broken ribs.

New players had their clothes torn to shreds in the dressing room, or worse, set ablaze. Hijinks occurred at every turn. The main culprit was ex-West Ham coach Wally Downes. A former apprentice, Downes infamously dangled club physio Derek French from a boat by his ankles to see how long he could stay underwater.

Later, one bus driver resigned from his post after (first) a cardboard box was placed on his head as he drove at 80mph down a motorway and (second) a layer of piping hot fish batter was placed on his bald patch. “There was even a radio news report when somebody saw one of our players naked on top of a minibus,” says Noades.

“We had good laughs, but when we were working we were f***ing working,” says Bassett. “The players didn’t go out there buggering about. They knew that if I got the hump, there would be a four-mile run around Wimbledon Common. The discipline was there.”

Goals galore

It worked, too. In ninth place as Bassett took to work, Wimbledon went on the rampage, finishing fourth and securing promotion. What followed was a period of ups and downs: relegation again in 1982, a Division Four title in 1983 (when the club scooped £25,000 from Capital Radio for being the first London side to score 80 goals), followed by promotion to Division Two in 1984. Noades then convinced Bassett to join him as manager at Palace; he agreed, only to change his mind and return to Plough Lane four days later.

This proved a shrewd about-face. Under Bassett’s management, Wimbledon had become a very effective unit. Hammam had already taken out a £100,000 bank loan, using Bassett’s house as a guarantee, and the manager had embarked on an understandably careful shopping spree.

Striker Alan Cork was an early arrival in 1978 from Derby, and he was followed by goalkeeper Dave Beasant (£100 from Edgware Town), defender Nigel Winterburn (£15,000 from Oxford United) and midfielder Lawrie Sanchez (£29,000 from Reading). Not that people approved.

Wimbledon’s ‘direct’ approach and physicality (they were ticked off by the FA for a “reckless” number of bookings in 1982/83) made them public enemy number one. That image was consolidated when, in 1986, with the Dons settling into their second season in Division Two, Bassett signed towering striker John Fashanu from Millwall for £125,000.

The arrival of ‘Fash the Bash’ proved inspirational. Wimbledon went unbeaten for the remainder of the season and gained promotion, unbelievably joining the big boys of Hoddle, Rush and Robson. “That was special,” says Bassett. “We knew all the top teams would be coming to Plough Lane. All of a sudden we were in the big league.”

As they arrived in Division One for the first time, one misconception of the Crazy Gang overshadowed their achievements – one that dogs them to this day. On first impressions, most fans refused to believe they had a football philosophy, and that the team’s style was primitive and based on aimlessness and brute force. But the reality was very different.

Bassett asked his team to play direct because he knew it was effective. After studying many matches on video with a statistician – known simply as ‘Vince’ – and reading The Winning Formula by former FA director of football Charles Hughes, Bassett discovered that more goals were scored if the ball was played quickly into the opposition’s half, usually in no more than three passes.

According to stats, while the initial attack might not deliver a goal, the resulting corners, throw-ins and free-kicks often created a spell of sustained pressure, hence the sight of Beasant launching a goal-kick down the park, or full-back Winterburn playing a 70-yard pass from the edge of his penalty area.

“Our fans liked the way we played: there was a lot of goalmouth action,” says striker Carlton Fairweather. “The ball got forward quickly and there were a lot of crosses and shots.”

Opposition fans complained of neckache as they watched balls sailing through the air; critics dismissed Wimbledon’s strategy as nothing more than a ‘hoof’ upfield. “People moaned about us playing ‘long ball’ because they reckoned it was easy to play in that way,” says Bassett.

“That’s a fallacy. It’s actually very hard because you have to play the ball into the right areas and everyone has to be on their game. Everyone knew exactly where they had to be and we worked on it every single day.”

The techniques used by Wimbledon were, in fact, based on a style of training first employed by AC Milan manager Arrigo Sacchi. On a full-sized pitch, Bassett would organise shadow training sessions. Without a ball, he would manoeuvre his players around the park like chess pieces, detailing their exact positions whenever a pass was played from a certain position into the opposition’s half. “There was a level of complexity going on that people outside the club didn’t appreciate,” says Fairweather.

It wasn’t just tactically that Bassett’s approach was cutting edge: his delivery of information was ahead of its time too. Opposing teams were studied for weeks in advance. With notes at the ready, Bassett was able to deliver a detailed breakdown to his players of exactly where their opposition appeared vulnerable.

Each analysis came with a highlights package and stats. “I had a guy cutting up videos for me – I don’t think anyone else was doing that at the time,” says Bassett. “We were never given any credit for it, but we didn’t care two sh*ts.”

“We let the stories and hype get exaggerated”

Bamboozling opponents with a succession of carefully planned long balls was one thing; creating a false sense of inferiority was another. Clubs, especially those in the top flight, thought the team were as reckless on the training ground as they were in the dressing room, a pub team operating among the big boys. They were wrong, and Bassett’s smoke-and-mirrors campaign earned the Dons a fair share of the spoils when it came to matchday.

“The press picked up on the burning of clothes,” he says. “We had characters and the press loved it, but we let the stories and the hype get exaggerated. We fancied the idea the other teams thought we weren’t preparing well. We knew we were organised. We had spin doctors before anyone had even heard of ‘spin’.”

Upon reaching the top flight in 1986, Wimbledon discovered they had another secret weapon: Plough Lane. Compared to some of the more modern grounds in the league, this was a dump, its grim exterior matched by down-at-heel dressing rooms and a claustrophobic atmosphere.

On this grotty battlefield, Wimbledon waged psychological warfare, playing all manner of tricks to get an edge over their opponents. The heating in the away dressing room was turned up too high, the loos didn’t flush and Hammam would often swap the sugar in the club bowls for salt, much to the disgust of the players as they came in for their half-time cuppa.

When the players exited their dressing room for kick-off, they were met with the sight of Fash, Vinnie and Dennis ‘The Menace’ Wise eyeballing them. “The players’ tunnel was one of our secret weapons,” said Fashanu later. “It was like the Tunnel of Doom. It might not have been Anfield, but a lot of players were scared to death. When they got in at half-time or after a game and it got dark, things happened.

"They got closer and closer and realised there was no light in there, and they weren’t sure whether they were going to come out on the other side. We used to go out screaming and come in screaming. And when the echoes rang round, you could see the fear in their eyes.”

The mind games weren’t restricted to home games, either. Away, the club would bring their stereo into the dressing room blaring house tunes out at full blast. “The lads didn’t respect any team that we played against,” says Fairweather. “One game at Everton, they knew we were coming along with a stereo and they turned off the power in our dressing room so we couldn’t plug it in. But we were very resourceful, so we had batteries with us.”

This Is Wimbledon

Their imagination paid dividends. The Crazy Gang lost to Manchester City on the first day of the season but went top of the table after consecutive wins against Villa, Leicester, Watford and Charlton, and eventually finished sixth (also reaching the FA Cup quarter-finals).

“I remember beating Manchester United,” says Lawrie Sanchez. “It was during the time you could pass the ball back to the keeper. We got it straight back to Dave Beasant from kick-off, he kicked the ball upfield and it bounced on the edge of the United box. I’ll never forget [United captain] Bryan Robson’s face. He looked around as if to say, ‘F*** me, here we go. We’ve got 90 minutes of this.’ We loved it.”

Even reigning double-winners Liverpool were beaten 2-1 at Anfield. Typically, the legacy of 16 league titles and four European Cups left Jones unimpressed: the midfielder augmented the famous ‘This Is Anfield’ sign with a piece of paper saying ‘BOTHERED!’.

How times have changed. Or maybe not. AFC Wimbledon's story echoes the early achievements of the Crazy Gang, though given the current financial discrepancy between top flight and bottom, the odds of similar success are stacked against their current vintage. At least their predecessors’ achievements should act as inspiration.

“The amazing part is that the players and everyone at the club have never been given credit for what they achieved,” says Bassett. “For the people involved, though, it was a special period and we were a special team. No one can take that away from us.

“People tried to knock it, but it’s easy to say it won’t be done now. But who knows? When we did it, we had a dream, and we proved that dreams can come true.”

This feature originally appeared in the October 2011 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Joe was the Deputy Editor at FourFourTwo until 2022, having risen through the FFT academy and been on the brand since 2013 in various capacities.

By weekend and frustrating midweek night he is a Leicester City fan, and in 2020 co-wrote the autobiography of former Foxes winger Matt Piper – subsequently listed for both the Telegraph and William Hill Sports Book of the Year awards.