Holland's most hate-filled fight club: Ajax vs Feyenoord

The famous Dutch tolerance is nowhere to be seen when the country’s fiercest rivals square up, as Andy Mitten found out for the April 2007 FourFourTwo magazine. Expect home-made bombs, attacks on players, sick chants and violence. Lots of violence...

An angry crowd awaits the arrival of two double-decker trains carrying the 1,600 travelling Feyenoord fans to the Amsterdam Arena. Preventing the couple of thousand baying Ajax fans from making contact with their hated foes is a security operation of immense proportions.

Up in the leaden skies, a police chopper surveys the scene while, above that, a 747 makes its final descent into Schiphol Airport. Ajax fans gather between the stadium, their team’s training pitches and a train station which has a tunnel linking the platform to the away end. In front of them, two lines of police wait, poised in robo-cop gear, their batons and shields ready for the inevitable.

One has a fire extinguisher attached to his back; others restrain agitated dogs. Behind, a line of police horses creates a further barrier. Add in two phalanxes of police vans, assorted security officials and officers with surveillance cameras, and you get an idea of the measures in place to keep supporters of Holland’s two biggest clubs apart.

A clutch of plain-clothes officers loiter nearby. Every few minutes they identify a problem fan and close in, before dragging him into a van where they administer their own form of justice. Most fans cover their faces with scarves, yet one seems determined to attract police attention, clad as he is in a gas mask and white boiler suit with a Feyenoord cockroach (Ajax fans call their rivals ‘cockroaches’) painted on his back.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

It’s an hour before kick-off and FourFourTwo is here to witness at first hand the maelstrom around Ajax vs Feyenoord, the biggest, angriest and most eagerly anticipated game in Dutch football.

Tale of two cities

That Amsterdam and Rotterdam are different is obvious as soon as you leave the latter’s central station. The buildings are newer, taller, bolder and construction cranes are everywhere. Rotterdam has remained a building site since the war, and while some of the developments have been lauded, many others are loathed. It is a hard, mainly working-class city, the second biggest in Holland (population 1.1 million compared to Amsterdam’s 1.5m) and boasts the largest port in Europe; globally, only Shanghai is bigger.

Rotterdam has the highest percentage of non-western foreigners in Holland, with nearly half the population not native to the Netherlands, or with at least one parent born outside the country.

The two cities are also increasingly polarised politically, Amsterdam remaining liberal to socialist as Rotterdam becomes more right wing (though the city has always been a labour stronghold). The controversial politician Pim Fortuyn, who was assassinated in 2002, set up his anti-immigration party here.

Amsterdam to party, The Hague to live, Rotterdam to work

Rotterdam’s inhabitants believe that civic pride matters more here, and the locals are proud of their home city’s industry. As the Dutch sayings go: ‘While Amsterdam dreams, Rotterdam works’; ‘Amsterdam to party, Den Haag [The Hague] to live, Rotterdam to work’.

Unlike Amsterdam, which has but one Eredivisie club, Rotterdam is a three-team city, with Sparta and Excelsior currently playing in the top division. While smaller clubs like AZ Alkmaar and Twente Enschede have challenged the Ajax-PSV-Feyenoord triumvirate, it’s an achievement for the smaller Rotterdam clubs just to be playing top-flight football.

The smallest, Excelsior, are on friendly terms with Feyenoord, but many conservative Sparta fans prefer Ajax to ‘the people’s club’, with Ajax gleefully reciprocating the feeling by singing “Sparta is the club of Rotterdam!”

Waiting in a bar by the station is Danny, one of the main Feyenoord lads and part of the SCF (Sportclub Feyenoord) firm. Now in his forties and working on the docks, Danny has followed Feyenoord all his life. He doesn’t like Ajax or Amsterdammers “and their stupid accents”, but he admits that Ajax have the edge when it comes to trophies and beautiful football: the Ajax board’s policy statement commits the club to ‘creative, attacking, dominant football’.

Ajax's utopia is to be like Feyenoord – a real football club with real fans. When it comes to supporters, we eat them for breakfast

“And yet,” says Danny with a smile, “their utopia is to be like Feyenoord – a real football club with real fans. When it comes to supporters, we eat them for breakfast. Ajax talk about the F-Side and Gate 410 being noisy. That’s two sections. The whole of De Kuip is noisy.” Most Ajax fans concur – the one area in which they respect Feyenoord is the atmosphere at De Kuip.

“Ajax is the team of celebrities, the media and phonies,” continues Danny. “Their main stand has more executive boxes and posh seats. People go there to be seen; people go to Feyenoord to support their team. Everyone hates Ajax’s arrogance and the media bias towards them.”

As he speaks, Rotterdam-based lawyer Erik scribbles Feyenoord’s anthem on a piece of paper. A Manchester United fan who has travelled to over 300 United games since 1978, Erik’s no anorak, but he’s also seen games at all 92 Football League grounds, plus 28 grounds in Scotland.

“Here,” he says, passing over the sheet of paper. It reads:

‘Hand in hand comrades,

Hand in hand for Feyenoord,

No words but action,

Long live Feyenoord!’

Danny has brought along hundreds of photos of Feyenoord fans. There’s one of a mob who travelled to Amsterdam by boat leaving Rotterdam at midnight: “We had a house party with DJs on board. Everyone was drugged up and dancing, but when we arrived in Amsterdam the police were waiting for us.”

He’s got pictures of a game at De Meer in the early '90s, when Feyenoord fans threw a home-made bomb into the Ajax section, causing injuries, some serious, to 18 fans. And he’s got shots of a wrecked television studio after Ajax and Feyenoord fans were invited to a live show. Fighting before the show meant the programme was never recorded.

History lesson

The enmity between Holland’s biggest two clubs is long-standing. Ajax have four European Cups, but Feyenoord were the first Dutch team to win the trophy, beating Celtic in 1970 under the Austrian Ernst Happel, whose team talks famously amounted to one sentence: “Gentlemen, two points.” Then Ajax’s Rinus Michels adapted the style of Happel, called it totaal voetbal and Ajax won three European Cups.

That outcome is typical of a rivalry in which Feyenoord have enjoyed only brief interludes of one-upmanship. In 1983, Ajax legend Johan Cruyff moved to De Kuip. Aged 37, he led Feyenoord, with a young Ruud Gullit, to the double. “He was the conductor for our orchestra,” recalls Danny. “And we had a beautiful orchestra.”

The message is clear – Cruyff was a genius, but Feyenoord had a great team. Yet to Ajax fans, it was their man who led Feyenoord to glory. Even when Feyenoord last won the league in 1999, Ajax beat them 6-0 in one of the final games of the season.

The rivalry is defined by prejudice, but there are many similarities, perceived and otherwise, between these bitter enemies. Both clubs claim support from well beyond their city boundaries; there are 1,100 Ajax season-ticket holders living in Rotterdam and 400 Feyenoord in Amsterdam. Ajax fans have been known to make life difficult for celebrity Feyenoord fans living in their city, painting ‘Ajax’ on their houses.

Feyenoord midfielder Jorge Acuna was hospitalised after Ajax hooligans attacked him at a reserve-team match

Like bickering brothers, the clubs attempt to outdo each other at all levels. In the late-’90s, the Costa Rican Froylan Ledezma flew into Schiphol to sign for Feyenoord, but because Ajax had better airport contacts, Feyenoord’s representatives were left in Arrivals, while Ajax officials met Ledezma directly from the plane. He signed for Ajax, leaving Feyenoord furious that their foes had kidnapped the player, though they had the last laugh when Ledezma failed to shine in Dutch football.

In truth, though, the story represents a brief comic interlude amid the violence. Three years ago, for example, Feyenoord midfielder Jorge Acuna was hospitalised after Ajax hooligans attacked him at a reserve-team match. This season, Feyenoord bought Ajax’s fourth-choice striker Angelos Charisteas, scorer of Greece’s winning goal at Euro 2004. At his initial training sessions, he needed two security minders, having outraged some Ajax fans by claiming that Feyenoord was a ‘warmer club’.

NEXT: Beaten to death in a muddy field

Fight too far

Though safety fears can usually be allayed by bumping up security, a decade ago in Beverwijk, the mutual loathing became lethal. In a field by a motorway between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, the two firms clashed in a pre-arranged meet. The precise numbers are disputed but, like a scene from Braveheart, hundreds moved towards each other carrying bats, knives and poles. There were few police and it became known as the Battle of Beverwijk.

Feyenoord outnumbered their rivals and as Ajax retreated, a heavy-set asthma sufferer called Carlo Picornie was stranded. Picornie, 35, had once been a prominent hooligan, but by 1997 wasn’t usually active; however, he had come out of his hooligan ‘retirement’ that day, telling his partner that he was going to get something to eat. Picornie was beaten to death in a muddy field. Another Ajax follower who saw what was happening and went back to help him, was stabbed twice in the lungs.

The death stunned Holland. Some Feyenoord fans paid for an advert in a national newspaper offering sympathy and stating that it was never meant to happen; others celebrated the death. At the first Feyenoord-Ajax game afterwards, the majority of Feyenoord fans bellowed “You left your friend on his own” and held up inflatable sledgehammers.

All Dutch fans felt the repercussions with a nationwide campaign – ‘Football: don’t mess it up’. Now, if you want to travel away with Ajax or Feyenoord, you have to go through more identification checks than an MI5 job candidate. You can only travel on supervised trains, which are often delayed by the police. Flouting the alcohol bans can mean an immediate €450 fine, while police infiltrate ultra groups and have powers to phone-tap suspects. And when the visiting fans finally reach the opponents’ ground, they are accompanied and met by enough security to satisfy a third-world dictator.

Warm welcome

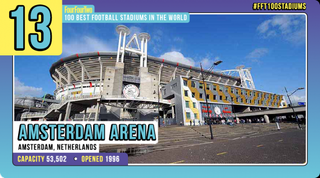

The first of the yellow trains appears on one of several elevated rail lines that surround Ajax’s gleaming home ground. An angry roar goes up, firecrackers explode and bottles are thrown towards the police. The crowd surges towards the formidable line of security in the vain hope of reaching the Feyenoord contingent, before police horses charge straight into the group, scattering people everywhere. Eleven fans are arrested and three officers wounded.

The train doors open and the Feyenoord fans spill onto the platform. The 43-mile journey should take an hour, but football trains deliberately travel more slowly with the heat turned on full and the windows closed to make the occupants drowsy.

Undeterred, and invigorated as the fresh air hits them, they immediately hurl abuse at the Ajax supporters 80 yards away. For decades they have traded insults via the media and websites, but only twice a year do they see the face of the enemy. One Feyenoord fan unfurls a Palestinian flag. “Hamas, Hamas – Jews to the gas,” chant some Feyenoord fans. “We are Super Jews,” retort Ajax, brandishing a Star of David.

They’re just kids. The real lads aren’t there, because if they did anything they’d get nicked straight away and their photos would be on television tomorrow

“They’re just kids,” says Longy, an Ajax hooligan observing the scenes. “The real lads aren’t there, because if they did anything they’d get nicked straight away and their photos would be on television tomorrow.”

Instead the hardcore Ajax hooligans are drinking in a bar at the opposite end of the Arena, close to the glass skyscrapers that house international blue-chip companies. As with the stadium, they were built to gentrify Bijlmer, a poor area of blighted '70s housing projects south of Amsterdam.

“It’s like Kinshasa over there,” says one lad, pointing to the housing on the other side of the rail tracks. “But it produces good footballers.” As with many new developments it’s a cold, sterile environment – but there’s a buzz today because Feyenoord are in town.

Firm approach

Longy’s peers, ranging from 17-year-old lads to granddads with gnarled faces peeking out from between their Stone Island jackets and Aquascutum caps, sip beer from small plastic glasses. The smell of cannabis is omnipresent. They know that, since Beverwijk, the police operation is so tight that they won’t get close to Feyenoord.

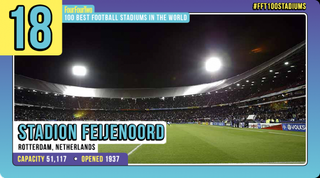

Ajax’s main firm is the F-Side, founded in 1976 and named after the section where their hardcore used to stand at Stadion de Meer, their home between 1934 and 1996, where Johan Cruyff’s mother washed the shirts. With a capacity of 22,000, it was less than half the size of Feyenoord’s De Kuip [literally, ‘the tub’] and hardly a suitable home for the 1995 European champions.

“De Meer stank of lager, p**s and burgers, and was an unsafe dump – but it was home,” recalls Longy. The move to the Arena was difficult, with fans who’d stood together for years spread around the stadium and bemoaning a new type of middle-class Ajax fan. The suspicion was that Ajax had deliberately diluted their most problematic support.

“After seven games we told the club the F-Side had to sit together again or there’d be problems,” claims one fan. “Nonsense,” counters a source who was a director at the club. “It’s dangerous to be influenced by fear and we weren’t.” Whatever the truth, the F-Side soon regrouped.

“F**k Rotterdam!” shouts a lad in English by the turnstiles. A family walk by, dad clutching a plasma screen bought from a shop close to the ground. They couldn’t look more incongruous if they tried.

What’s striking about the Amsterdam Arena is its height. Whereas some of the greatest venues in the world like the Nou Camp and Old Trafford have pitches below ground level, lessening their visual impact outside the stadium, the 51,000-capacity Arena’s pitch is 10 metres above ground level, on top of two floors of parking.

Today FourFourTwo is sitting with the F-Side, using a season ticket from another fan. His photo’s on the credit card-style season ticket and, frankly, he looks as scary as anyone we’ve seen so far, but when you go through the electronic turnstiles the operator checks your passport, not your season ticket, against a list of banned fans. The list is eight pages long.

It costs €15 (£10) to sit behind the goal – less than at many Conference North/South games – and for that you get an uninterrupted view from the lower tier, which is today bedecked in a 50-metre-long banner reading ‘Amsterdam – No Bullshit’.

“There’s f**k all in Rotterdam,” sing the 6,000-strong F-Side from behind the moat which separates them from the pitch, in reference to Feyenoord’s chances of success this season. Feyenoord have been thrown out of the UEFA Cup for crowd trouble at an away game in France. Had they stayed, they would have played Tottenham, who recorded the first-ever incident of hooliganism by an English club in Europe in 1974, in a match against Feyenoord.

NEXT: "They’re obsessed by us, far more than we are by them”

'Bombs over Rotterdam'

Despite the Sunday morning kick-off, the atmosphere crackles. As the start approaches, a flag is unfurled close to the away fans. Above the phrase ‘Bloody Sunday’, it shows the Rotterdam skyline and a German Messerschmitt bomber dropping its payload, as 90 of them did in the carpet-bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940. More than 800 were killed, 70,000 left homeless. (Holland immediately surrendered to Hitler, sparing Amsterdam from the same treatment.)

Firecrackers explode behind the goal as if to re-enact the bombing and the whole stadium holds up red, white and black cards. Then, to the tune of Tulips From Amsterdam, they chorus:

“When the spring is coming, we’ll be throwing

Bombs over Rotterdam,

Thousands of big ones and lots of casualties,

More dead than alive,

What the Luftwaffe don’t destroy,

The F-Side will.”

As if the fixture requires further stoking, today marks the return of a warrior hero: 16 years after his Ajax debut, Edgar Davids is back. His popularity has never waned and his return is celebrated on several flags; some are in English, like many around the ground – ‘Red & White Fighters’, ‘There Can Only Be One’.

There are many chants, too, imported from Britain, and as thousands sing “If you all hate Feyenoord clap your hands,” a giant Union Jack below the away end reads ‘Ajax Can’t Be Stopped’. Some ascribe this to the extraordinarily high numbers of English-speaking Dutch people (85% of the population has at least a basic knowledge of the language). Others mutter darkly about a fascination with old-school English hooliganism.

When the game kicks off, the players do their best to release the off-pitch tension, as if on police request. It takes barely half an hour for second-placed Ajax to surge into a 3-0 lead over fifth-placed Feyenoord. Davids is tenacious, but the star is playmaker Wesley Sneijder.

“Always look on the bright side of life!” chirp the Ajax sections. The visiting fans, hemmed in by security, three-metre-high walls and glass shields at the front of their section, are devastated. Even without their best player, the suspended Jaap Stam, Ajax canter to a 4-1 victory.

Staying for afters

While most home fans leave after Ajax’s lap of honour, the majority in Gate 410, close to the away fans, stay put. They’re Ajax’s second fan group, mainly made up of younger, more enthusiastic members than the F-Side. “We model ourselves on the tifosi of Italy, or the fans of Greece or Argentina,” explains one of the 410 leaders, who spends the match with his back to the pitch orchestrating the chants.

The abuse becomes more vicious. “You left your friend on his own,” sing Feyenoord. “Wherever in the world I’ve been, I’ve never seen so many Jews as in f**king Amsterdam.”

There’s a reason these songs start after the game. If the referee hears them during it, he has the power to stop the match, while the authorities will impose measures such as banning away fans or forcing games behind closed doors. And nobody wants that, no matter how vocal their hatred.

Feyenoord say we’re arrogant, but we support a better team. We’ve beaten them in their own stadium more times than they’ve beaten us. They’re obsessed by us, far more than we are by them

The Ajax fans head back into town, to a bar called Henry VIII. Posters of Ajax teams adorn the walls, with pride of place given to the 1995 European Cup winners. With names such as Patrick Kluivert, Clarence Seedorf, Frank Rijkaard, Marc Overmars, Jari Litmanen, Edwin van der Sar, Frank and Ronald de Boer, Danny Blind and Davids, it’s not hard to see why.

“Van der Sar got married in Amsterdam last year,” says Longy. “So 100 Ajax ultras waited for the wedding boat to pass along the canal. When it did, we let off flares. Van der Sar is down to earth. The boat stopped and they passed us all a beer.”

Longy hates Feyenoord so much that if he sees a Feyenoord book in a shop he bends the cover, and if he sees a car with a Feyenoord sticker he sprays ‘Ajax’ on it.

“Feyenoord say we’re arrogant,” he spits, “but we support a better team. We’ve beaten them in their own stadium more times than they’ve beaten us. They’re obsessed by us, far more than we are by them.”

We move on to a small bar in the busy red light district. In the street outside, a sympathy card hangs on a ribbon, marking the spot where a Middlesbrough fan was stabbed to death by a drug dealer before his side’s game against AZ Alkmaar in 2005.

By now some fans are coked up as well as boozed up, but all are buzzing because they’ve beaten Feyenoord. Dutch pop music blares out as Spurs play Man United on the big screen. (Many Dutch fans travel to England to watch their second clubs – Liverpool, United and West Ham are all mentioned – yet while the Ajax lads know that some of their Feyenoord counterparts go, they’ve never met them in England.)

“Today was brilliant,” gasps one refreshed fan as the night draws to a close. “F*** Feyenoord, f*** Rotterdam.”

Like all great rivalries, this one continues to rage – PSV could win the league for the next 20 years, but they’re dismissed as a factory team, for main sponsor Philips – but as FourFourTwo heads for the exit, we’re left to reflect that, for all today’s vitriol, Picornie’s death has had a positive legacy and families can now feel safer watching football in Holland. The situation has been improved, but only by implementing the most sophisticated security in Europe to keep rival fans apart. Italy’s football authorities may wish to take note.

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.

Most Popular