How Angel Di Maria's wasteful play is the key to Manchester United's season

Thore Haugstad analyses how and why Angel Di Maria's daring - and often wasteful - play is crucial to United's season...

In some ways, the most important player at Old Trafford is also the most wasteful. Since his Manchester United debut at Burnley in late August, Ángel Di María has attempted more ambitious passes, crosses and dribbles than other midfielders do in a whole season.

Often, it all goes awry. In fact, his pass completion rate is one of the worst at the club. Yet only a madman would change anything about it.

The reason, of course, is that some of it comes off. Since arriving from Real Madrid for £59.7 million, Di María has re-energised a previously pedestrian attack and established himself as the catalyst for the kind of highoctane football last seen under Sir Alex Ferguson.

When the 26-year-old is on the ball, something nearly always happens. If Daley Blind is the quietly efficient engine than keeps the United machinery running, Di María is the shift that cranks it into top gear.

The elementary statistics – 3 goals and 4 assists in 7 league matches – tell only half the story. On an average per league game, Di María has played 3.3 key passes (the closest are Juan Mata and Luke Shaw, with 1.3); he has fired 3.1 shots (only Wayne Rooney has more, with 3.2); and he has completed 2.7 crosses (the closest of those who have played 90 minutes or more is Ashley Young, with 1).

So many risks does Di María take, his pass completion is down at 80.7%. Only three players in the United squad are worse: David de Gea, the goalkeeper, Jesse Lingard, the midfielder who has played 24 minutes, and James Wilson, the 18 year-old forward who has attempted 4 passes all season.

Attack, attack, attack!

Part of the reason for Di María’s impact has been Louis van Gaal’s decision to hand him his favourite role. At least initially. Di María started out as a centre-left shuttler on the outside of United’s diamond midfield; a similar role to those he had at Benfica, his club prior to Real Madrid, and in his final season at the Bernabéu.

However, in the two most recent games, Van Gaal has readjusted to 4-5-1 because of Rooney’s three-match ban and Radamel Falcao’s injury. And so Di María has played wider with varying freedom to roam.

Yet regardless of his position, Di María’s effect on the side’s play has remained reasonably consistent. Analysing his attacking contribution, some patterns emerge.

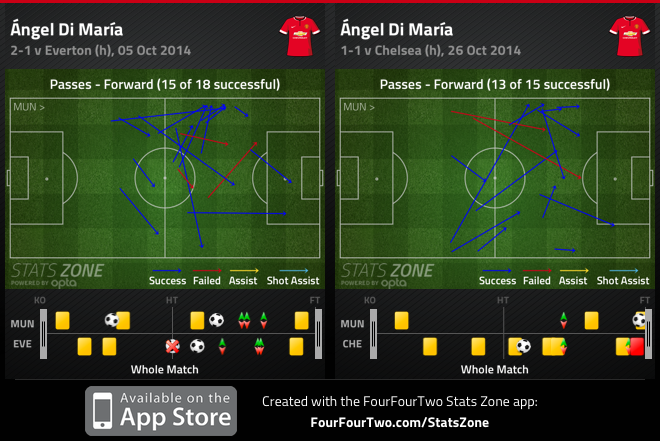

One example is his passing. At home against Everton and Chelsea, the two toughest games for United so far, his deliveries were uncharacteristically risk-averse, with most forward passes completed.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

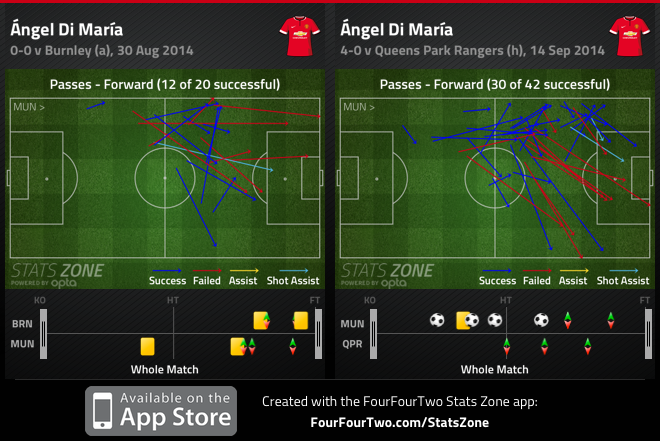

But against more unfancied sides, the story is different. When United’s primary task has been to break down compact defences, Di María has released a flurry of long passes in a bid to provide the creative spark. His deliveries were particularly erratic against Burnley and QPR, yet several also created danger.

The sheer number of forward passes reflects the nature of Di María’s mindset. His presence encourages proactivity. Against Burnley he attempted 20 forward passes and 33 passes in total, which means that about 60% were directed towards the opposition’s goal. Against QPR, 42 out of 76 were aimed forward, or 55%. Those are high numbers for a member of a primarily possession-oriented side.

Direct and daring

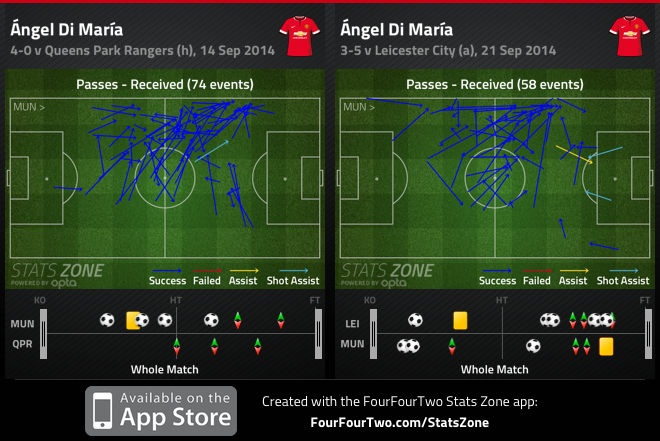

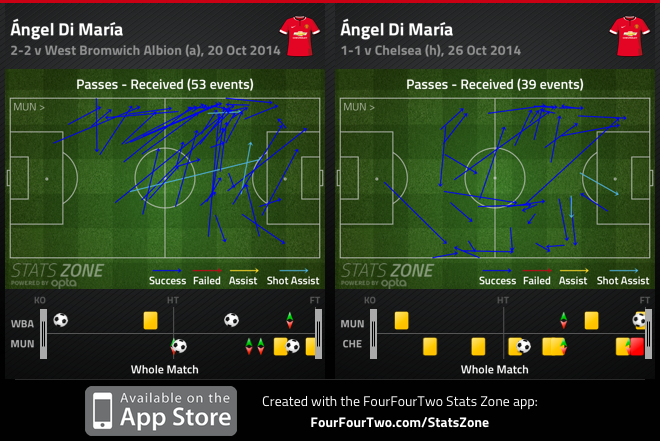

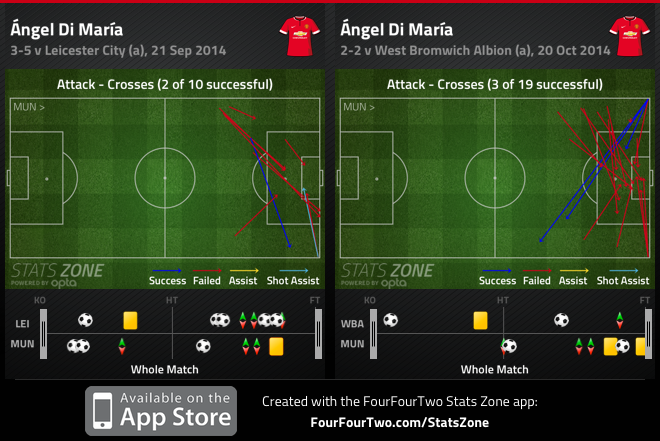

A similar audacity can be sensed in the crossing statistics. Often unfazed by initial failure, Di María continues to pump in deliveries throughout the game. This was certainly the case away to Leicester and West Bromwich Albion, where numerous inswingers were launched from the left-hand side.

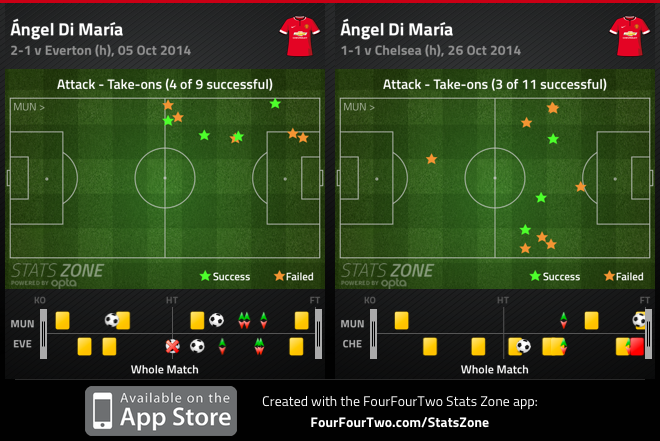

Meanwhile, in big matches, Di María’s output has appeared to change a little. While his passing has become more cautious, his appetite for taking on defenders has increased.

At home against Everton and Chelsea he attempted a notably high number of dribbles, living up to his apparent role as the player United entrust with making things happen.

Special allowance

As with most things Di María tries, the success rate can easily be criticised. But ball retention was never the reason for bringing him to Manchester. Rather, the mentioned observations may summarise what Di María’s end product really is: a mixed bag, at best, in which the good outweighs the bad.

When consulting our memories to assess his performances so far, our recollections of the spectacular tend to erase the occasional wastefulness.

What thoughts Van Gaal holds on the matter is harder to say, though the self-assured Dutchman suggested after the 4-0 win against QPR that Di María could still improve by stopping giving away so many passes.

That would be ideal. The question would then become whether that instruction would inhibit his carefree attitude towards the audacious. Creating a moment of genius tends to require more than one attempt.

Even if Di María has tightened up his passing game somewhat following Van Gaal’s comments, his role as chief creator remains clear, his licence to express himself still vast.

And that would be foolish to alter. In a managerial philosophy that centres on keeping the ball, Di María should be the one player allowed to lose it.

Man City vs Man United LIVE ANALYSIS with Stats Zone