How to be a football commentator: FFT finds out the hard way

As they launch their new partnership with the Deezer streaming service, talkSPORT invite FFT’s Chris Flanagan to their studios to learn the art of commentary…

It isn’t just a case of turning up and being paid to watch a game of football. There is more to it than some people think

It’s the first time FourFourTwo has ever commentated on a football match and our mind has just gone completely blank. Tom Rennie is showing us the ropes in a trial at talkSPORT studios, just a few blocks from Waterloo station in central London. He starts off in his normal role as commentator, we’re doing the summarising. We’re hoping these could be the first few words of a glorious career in commentary.

In a few short years we could be live at the World Cup final. Our summarising was certainly succinct. A little too succinct, in fact. Commentating on a rerun of Hull City’s May fixture against Arsenal, we join the action almost half an hour in. It’s 0-0 and Tom asks how impressed we are that the relegation-threatened Tigers have held off Arsenal’s quest for an opening goal.

“It is impressive,” we assert enthusiastically, before realising that we needed to come up with some of our own opinions, and quickly. “Hull need these points badly and I think...” There was no end to that sentence. We weren’t quite sure what we thought. Partly because we hadn’t actually seen the first half hour of the game, and partly because we were quickly finding out that commentary isn’t as easy as it seems.

“It isn’t just a case of turning up and being paid to watch a game of football,” Tom’s talkSPORT commentary colleague Jim Proudfoot explains later. “It’s a fantastic job and you look forward to going to work. I appreciate that I’m lucky to do it. But there is more to it than some people think.”

Things get a little easier for FFT when we switch roles with Tom, with Arsenal now 2-0 up. We do the commentary, he takes over the summarising. Now there are foundations to build around. As lead commentator, describe what’s happening out on the pitch.

It’s still far from easy, though. Suddenly players we’ve watched for years, even interviewed, seem like strangers as the action develops at speed. Who made that tackle? Was it James Chester? We say it was - and we’re right - but the hesitation in the voice gives away the fact that, for a split second, we weren’t sure.

On other occasions, we’re keeping it vague, too vague, and commentary clichés are spilling out. Without doing it deliberately, the voice has gone into ‘commentator mode’, a marginally better spoken version of our actual voice. We imagine we’re starting to sound like Bryon Butler from that video of the 1986 World Cup we watched avidly as a kid (‘Maradona, he turns like a little eel’). In truth, we’re far from that.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

As co-commentator, Tom is reeling off insightful analysis off the top of his head. Having struggled for words ourselves in the summarising role only a few minutes earlier, we’re impressed. But slowly we’re becoming a little fluent. By the time Arsenal score their third, we manage to describe the goal relatively competently.

Without doing it deliberately, the voice has gone into ‘commentator mode’, a marginally better spoken version of our actual voice

“You could have sounded more excited!” Tom chuckles later. In fairness, the goal did happen five months ago...

OK, we didn’t deliver the finest few minutes of commentary that the world has ever heard. Writing’s our thing. But it wasn’t half fun. Imagine how much we would have enjoyed it if we’d been any good? “When you’ve done a big game and you’ve nailed it, there’s a big goal and you’ve done a good job of it, it is an immense satisfaction,” Proudfoot says, before giving us a few tips about how to get it right as a football commentator...

Don’t have nightmares, be prepared

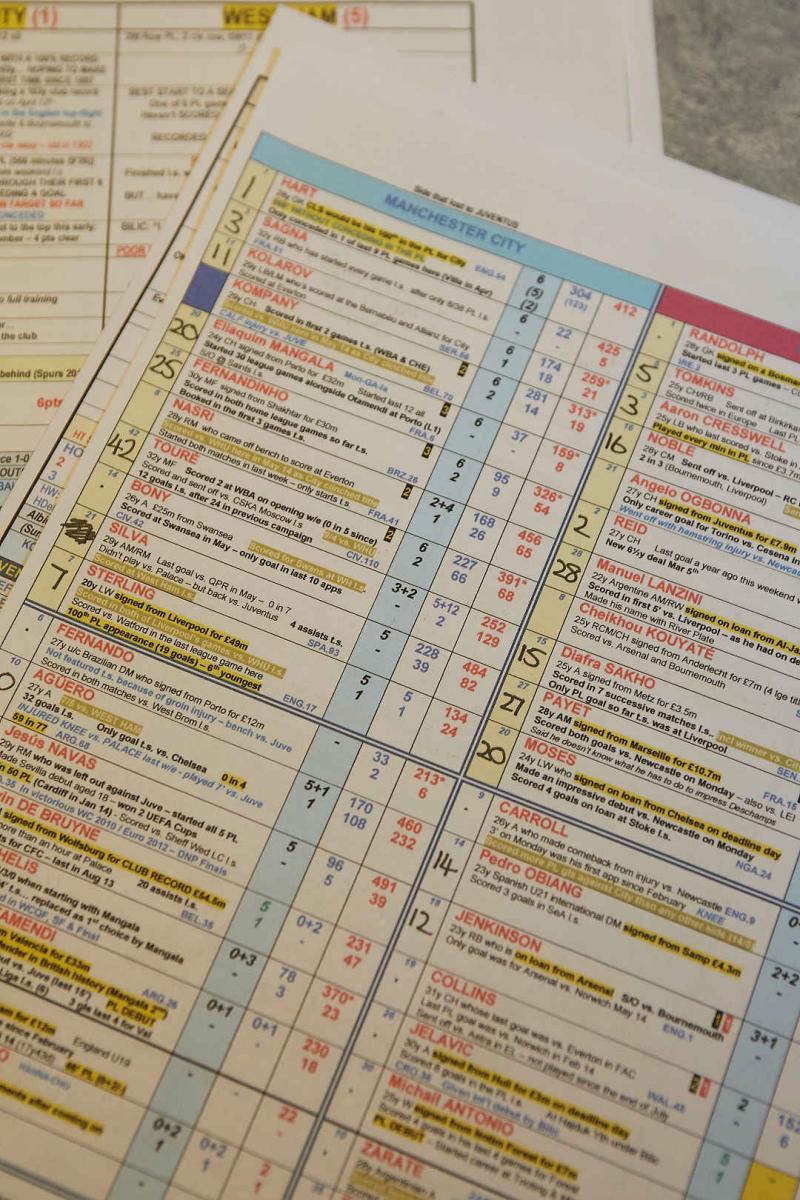

“You have to go into it with a mindset that it can be quite hard work,” Proudfoot says. “I do seven to eight hours of preparation for every game. It’s mostly time spent on the internet. I read as much preview material as possible to try to find storylines. That’s how American commentators do it, they’ll have production meetings and they’ll discuss the storylines in specific games. At a game I have two sheets of paper in front of me. One has all the players who are likely to play and quite a bit of detail on each of them.

"The aim is that I won’t say 80 or 90 per cent of what is written down. If I said it all, it would be a disjointed commentary too laden in statistics. But you don’t know what’s going to be relevant, so you need to have all the information. On the other piece of paper, the top half is facts about each team and the bottom half is blank. That’s where I write the team formations, goalscorers and substitutions.

“Sometimes to prepare I’ll watch part of a previous game on television. I did an Ipswich game recently and I hadn’t seen them play beforehand this season, so I watched a game they played live on Sky. It’s learning recognition, being able to see a player and say who it is. European matches can be tricky because often you won’t have seen one team play before. But if you know one side you can pick the others up pretty quickly.

"If you don’t know either side, by half-time you still won’t know either side because it’s just too much to take in. A lot of people dream about work and my recurring nightmare is turning up and not having a team-sheet, not knowing who the players are, my equipment not working or getting thrown on air and having to fill. I probably dream that two or three times a month!”

Paint a picture for the listener

“From a radio point of view, the main thing you have to do is make sure you provide an accurate description of what’s going on,” Proudfoot explains. “The most important things that the listener wants to know – because people are tuning in and out all the time – are what the score is and where the ball is. Also in commercial radio, ratings drive advertising so we remind people what they’re listening to. Every couple of minutes or so, you’ll remind people what the score is and say: ‘You’re listening to talkSPORT’.

The most important things that the listener wants to know – because people are tuning in and out all the time – are what the score is and where the ball is.

“The key is to provide fast and accurate description of what you can see. If the ball’s in the final third you’ll be talking about what you can see - where the ball is, has it been played into the box strongly? It’s not just a question of naming names, you’re trying to paint a picture in the mind of the listener about what is happening.

“If the ball’s in the middle of the pitch, you can talk about other things. You keep an eye on what’s going on but you can bring in your co-commentator for analysis, and produce interesting facts.

There’s nothing worse if you’re sat there listening than if I’m prattling on about the fact it’s the 29th time in 40 years that a team has won a corner in the third minute of the game, and you hear a massive roar from the crowd. You’re wondering: ‘What’s happened? Tell me what’s going on!’

“It’s quite difficult to get the balance right between telling the story of the game, contextualising it and giving an accurate description of what’s happening. There’s nothing worse if you’re sat there listening than if I’m prattling on about the fact it’s the 29th time in 40 years that a team has won a corner in the third minute of the game, and you hear a massive roar from the crowd. You’re wondering: ‘What’s happened? Tell me what’s going on!’

“If you’re not sure who has the ball at a particular moment, on radio you don’t have to talk about that passage of play. You can talk about other things. If I say he’s passed it to Kouyate and you’re listening in your car, he’s probably passed it to Kouyate. He might not have done, he might have passed it to someone else...

“On radio you don’t have to beat yourself up over every single mistake you make but if you get the goalscorer wrong, you do beat yourself up, believe you me. It’s a terrible thing to do.”

Capture the moment

In South America, commentating on a goal is simple. Just shout ‘Goallllllll’ until you’ve virtually passed out and everyone’s happy. In England things are a little different.

“You couldn’t get away with doing every goal like that over here,” Proudfoot says. “If you’re commentating on a goal that wins England the World Cup, it’s something that’s going to be played over and over for years. You don’t just want to be shouting ‘Goal!’ for 20 seconds because you’re not doing the moment justice.

“It’s trying to convey excitement and make sure what you’re saying is still intelligible. One of the great moments of commentary was when Manchester City won the title and Martin Tyler shouts ‘Aguerooo!’ It was perfect because he’s got the emotion, the sheer drama in his voice, then he says ‘I swear you’ll never see another moment like that’. In less than 15 words, he completely nailed the moment.

“As I’ve got older I’ve learned not to get too excited too quickly. I remember doing an England game in Euro 2004 against Portugal when Michael Owen scored early on and I went completely off the scale. Someone asked me later: ‘What were you going to do if England scored a second? You left yourself nowhere to go’. When I first started as a commentator I thought I was doing a good job, but I would hate to listen back to the first games I did in the mid-90s. I was working for local radio in Manchester in the year that United won the Treble. I have heard a couple of bits of commentary and it was over the top, too many hyperboles.”

Don’t script your lines

“I don’t think you can decide what you’re going to say before the game,” Proudfoot says. “Yes, think about if a certain team scores, what’s the relevance of that? But don’t write down ‘this is what I’m going to say if this player scores’. You’ll get found out. The listening public is so football savvy that people see through it.”

Adapt your style for television

“The essential difference between radio and TV is that on radio you’re telling people where the ball is and describing in some detail what’s happening,” Proudfoot explains. “On TV you can’t do that, because people can see it. There’s no margin for error, either. If you get something wrong, everyone can see it.

There’s no margin for error on TV. If you get something wrong, everyone can see it

“It’s finding ways to describe the action without saying ‘he has passed it to him’, whereas if you do that on radio it’s too vague.

“There aren’t many people who do both radio and TV, flitting between the two. Sam Matterface does a lot of television for ITV and does radio here at talkSPORT and alternates between the two perfectly, but it isn’t the easiest thing to do because there is a conscious change. You couldn’t do television commentary on radio or vice versa. It wouldn’t work.”

Make good use of your co-commentator

It’s amazing how quickly you get into the rhythm of who speaks when

“If there’s a break in play I would expect my co-commentator to come in and have something to say,” Proudfoot says. “What he’s doing is explaining why what has happened has just happened.

"The best summarisers can forensically dissect a passage of play that they’ve just seen and say why something has happened. Stan Collymore does that so well for us.

“On television it’s a little bit simpler because generally when there’s a replay that’s the co-commentator’s domain. When there isn’t a replay, that will be the commentator, although he will ask questions. It’s amazing how quickly you get into the rhythm of who speaks when.”

Research pronunciations

“This season there is something online we can access where we can hear the vast majority of Premier League players saying their own name,” Proudfoot says “The Premier League have always done the videos where players walk in front of a green screen and fold their arms. Now they say their name as well.

“If it’s a foreign team there are YouTube goal clips, and sites where people upload pronunciations of players’ names. They’re mostly accurate, although not always.

If I go on air and say Ya-jel-ka when he’s been playing for 15 years, people are going to think I’m being pretentious

“If you still don’t know, you have to see someone at a game and not be afraid to say: ‘I’m really sorry but the number 72 for Manchester City, what’s his name?’ You can still get three or four answers but you have responsibility as a commentator to make the pronunciation as accurate as you can.

“The problem comes when you’ve got Everton’s England international central defender who isn’t John Stones. Phil. What’s his surname? Ja-gi-el-ka is what everyone calls him, but it’s not what he calls himself. He pronounces it Ya-jel-ka.

But if I go on air and say Ya-jel-ka when he’s been playing for 15 years, people are going to think I’m being pretentious. I’ve had conversations about Phil with commentators three times recently. What do we call him? We all want to call him Ya-jel-ka now but the tannoy announcer at Everton is still saying Ja-gi-el-ka.

“Freddie Ljungberg is another. His name is pronounced nothing like how we pronounce Ljungberg, it’s something like Jun-ber-a, but if I’d said that people would have thought that Arsenal had gone out and bought a new player, and crashed the car in shock! The worst one for me – and I didn’t make a very good job of it, I’m ashamed to say - was during a Greece Under-21 game against England.

"The one that caused me the problems was Sokratis Papastathopoulos. What made it worse was there was another player in the team called Papadopoulos. Papadopoulos and Papastathopoulos. They possibly both played at centre-half and inevitably one of them scored.

“You’ve got a header from a corner and you’ve got to call it straight away. I was thinking: ‘I don’t believe this, he’s going to score here.

"Am I going to be able to say it quickly in an excited manner?’ I don’t think I did in fairness! But I think I’d be all right with him now. I might just call him Sokratis!”

Listen to live talkSPORT commentary from the Premier League and FA Cup with streaming service Deezer through its new ‘football’ section, which includes podcasts, fixtures, results and more. Catch live football action for free at dzr.fm/ftball as well as enjoying the world’s biggest music streaming library.

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.