How to build a new stadium – by those who have

FFT’s Chris Flanagan asks the experts how to move ground. Turns out it involves orchestras, roses, a Queen impersonator, Christmas cake and Ken Bates...

After almost a quarter of a century in the stadium business, Paul Fletcher chuckles as he remembers how hard he tried to avoid ever getting involved in the first place.

"I took the job as commercial manager at Huddersfield Town on condition that I had nothing to do with the new stadium they were planning," he tells FFT. "But within 12 months a new chairman took over, dragged me into the boardroom one afternoon and said, 'It’s your job to build us a new stadium'. I didn’t know anything about the building industry, or the stadium industry."

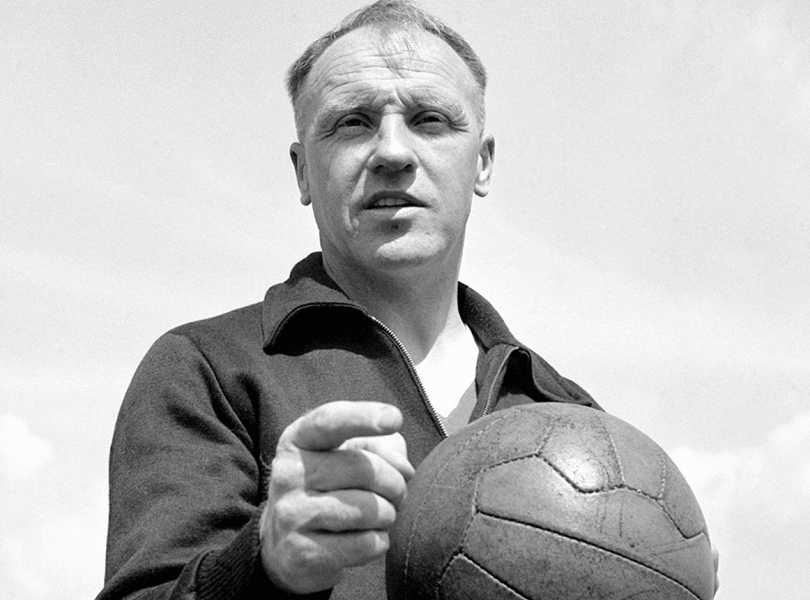

Today the former Burnley and Bolton Wanderers striker is working on stadium projects in three different continents. His work at the McAlpine Stadium as it was first known, then at the Reebok Stadium and the new Wembley, quickly made him one of the most respected men in the business.

Orchestras, roses and rides

"I just got stuck into it at Huddersfield," he says. "My role was almost like the orchestra leader. I didn’t know how to play any of the instruments, but I could get everyone playing the same tune.

We literally built one stand at a time. Future generations could finish it off”

"At first I was what they call a naive client though. Everybody knows you've never built one before so they do two things. They send you bunches of flowers to tell you how much they love you, but at the same time they take you for a ride all around the houses – whether that's the architects, the project managers, the structural engineers.

"When we started at Huddersfield all we had was £4m from the sale of their old Leeds Road site, so we decided we needed to build a stadium literally one stand at a time because we knew if we could relocate, future generations could come and finish it off.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

As is so often the case, finance was the tricky bit: raising enough to make a statement stadium without denying the manager key funds.

"Always the most difficult thing is the fund-raising,” says Fletcher. “You never quite have enough money, no matter how hard you try. Plus the more you spend on your stadium, the less you have to spend on your team, so you have to be careful you don’t weaken the team.

"The stadium cost £29.5m and we were only about £5m short. We did really well with our fund-raising, so we were able to build three stands. We just had to visit various pots for grants.

“The Football Trust had a pot of money to give to any club wanting to build a new stadium, then we had the idea to play rugby league there because we knew if we played international rugby league matches there, that gave us an extra £1.5m.

“The local authority had some grants that they were able to call on and because we were building a community stadium – with football and rugby on the same pitch for the first time ever – we brought in a lot of funding that we didn't think we'd get. We just pieced it all together.

"We won the Building of the Year award, which was a great accolade – especially because it only had three stands! But we knew we were building something iconic. A stadium with the curvature of the roof like that hadn't been done before."

The Wanderer returns

It was the success of that first project at Huddersfield that paved the way for a career in the stadium business. Fletcher's boyhood club Bolton were soon on the phone asking him to help with their relocation to the Reebok.

"I used to go with my dad and my grandad to watch games at the old Burnden Park,” recalls Fletcher, “then I was responsible for demolishing it and helping to relocate six miles up the road.

Fans won’t travel two miles out of a town centre"

"By the time I got there the design was almost set in stone, but I got involved in things like naming rights. Every club has a number that they think they’re going to get for the rights. It’s many millions of pounds and if you get it wrong, you’ve got a big hole in your business plan.

"I thought we did very well with a great name like Reebok but the mistake with the stadium I think was that it’s too far from the town centre. Bolton were in the Premier League for a long time but the crowds didn't increase. I've realised that there’s a distance that fans won’t travel and I think that’s about two miles out of a town centre."

Wembley – and Ken Bates

After Bolton came the political minefield of the Wembley project. Lottery funding had initially been provided on the proviso that the new national stadium was also used for athletics, only for plans to be controversially changed by stadium chairman Ken Bates.

Just to let you all know, we’re not having a running track. I’m not bothered what anyone says”

"The early design of the stadium had a running track around it," Fletcher says. "I went to a meeting one morning when Ken Bates stormed in. He said, ‘Just to let you all know, we’re not having a running track. I’m not bothered what anyone says, we’re going to build the best football stadium in the world. If we put a running track around it, the fans will be too far away'.

“Love or hate Ken Bates, he made that decision almost on his own bat after taking £100m off UK Athletics and the National Lottery. He made quite an immense decision on his own and I don’t think anyone’s ever thanked him for it.

“He got dragged in front of a Select Committee of the House of Commons and got grilled for it but he stuck to his guns. I think he’s achieved what he set out to achieve, the best football stadium in the world.

"But it was a tough time for me at Wembley. I have to say maybe I was a little bit too soft for the London market. I’d always been very much a team player, as a footballer and in my stadium work. I’d always wanted to do fair deals. That was the way I did my business. It seemed an awful lot tougher in London.

Wembley cost double the original budget so the commercial income had to increase – but there’s only so much that people will pay”

"My role was to overview the commercial income – the corporate packages and the catering deals – then we had to project the size of the crowds for England games, ticket prices and all these things.

"The stadium came in at around double the original budget and I started to come under pressure because the commercial income had to increase. But there’s only a certain price that people will pay – as you see today when people complain about ticket prices. The cost of a box, the cost of a hamburger, there's only so much that people will pay to watch football.

"But we introduced Club Wembley, a type of 10-year debenture. Local businesses would buy two, three, five seats and use them to entertain their customers or for friends and family. That was a vital revenue stream for Wembley and it's performed very well. That club level brings in £40m or so, which is significant money.

Corporate guests and the “Christmas cake” Twin Towers

The new Wembley has sometimes drawn complaints as swathes of seats lie empty after half time, with corporate customers taking their time to return to their seats. It could have been even worse but for design changes.

"You always put your corporate seats in the middle tier but in the very early designs the banqueting suites were below ground level," Fletcher says. "It would have been about 10 minutes for every journey.

“So I worked hard for a few months with the architect to relocate the key banqueting suites into the middle tier, then the people buying the prawn sandwich tickets could literally walk straight out into their seats. Can you imagine if those people had to go up and down two sets of escalators? It would have been a nightmare."

With the Twin Towers gone, Fletcher also had plans for the arch – although those dreams were eventually dashed.

Wembley’s Twin Towers were like the icing on a Christmas cake, you just touched them and they crumbled away”

"It was pretty obvious from day one that there was nothing you could do with the Twin Towers," he says. "Everyone thought they were made out of brick but they were made out of poured concrete. They were like the icing on a Christmas cake, you just touched them and they crumbled away. There was no way of relocating them, they just had to go.

"The first design of the new stadium had four spires but again Ken Bates came in one morning and said it looked too much like the Stade de France, that we needed something iconic. One of his friends was Lord Foster, who’d done a lot of architectural work. He came up with this massive arch.

"I tried to do something with the arch like they do with the Sydney Harbour Bridge walk. I thought it would be nice for football fans to say, 'You’re only a true England fan once you’ve walked through the arch'.

“Unfortunately, the health and safety people wouldn’t allow it. You could climb up one side but coming down the other side would have been too steep. It got scrapped, which was a shame really, because I thought that would have been wonderful."

Giving the old place a good send-off

Fletcher had able assistance at Wembley and his previous stadium ventures from his former Burnley team-mate Alan Stevenson, whose role was chiefly to focus on commercial revenue from closing down the old ground.

Stevenson has since gone on to fulfil a similar role at a variety of clubs including Hull City, Doncaster Rovers, Shrewsbury Town, Chesterfield and now York City, who are due to leave Bootham Crescent in May 2017.

"My expertise is maximising the move from the old stadium," he tells FFT. "I create an end-of-an-era package, celebrating the move. We bring out a big souvenir programme for the last match, 130-odd pages, which sells very well. We get teams playing on the pitch, corporates and fans can play, and we have a big farewell banquet with a marquee on the pitch. We also do a DVD of the history of the stadium, and a book as well.

Imagine moving house and times it by a thousand”

"A lot of money goes out of the coffers by moving: just imagine moving house and times it by a thousand. But you can make a lot of money too because it’s not just for this generation of supporters, it’s for their fathers and grandfathers who might not come any more but will want to come for one last time and be part of it.

"At all the grounds you go to, they move every 100 years or so, and there is nobody at the club who has experience of moving. I’ve picked up experience from the clubs I’ve been at and you learn. The secret is not to try to rip people off. You maximise what you make but you make sure supporters feel that they’ve taken part in a historic event.

"If you get it right, it goes really well and it's a really lovely feeling. It's the end of a stadium, it's quite emotive. You get grown men crying."

Auctioning off history (and Shankly’s loo seat)

One of Stevenson's typical initiatives is an auction of items from the old stadium. As well as the likes of turnstiles and seats, some more unexpected items are also available.

"At Huddersfield we auctioned off the toilet seat that Bill Shankly sat on when he was the manager there," he says. "It made £500. It was a dirty old wooden seat but a Liverpool fan bought it!

"There are lots of unusual things you don’t know about until you start delving into things. At Wembley we did an auction with Hugh Scully and we found a horseshoe. Remember the White Horse Final in 1923? No-one could believe it was that, and we didn’t sell it because we said we couldn’t prove it was and we couldn't prove it wasn't, but it created a lot of interest.

"There was also the crossbar from the 1966 World Cup final that we donated to the National Football Museum in Manchester, and we auctioned the piece of turf where the ball landed when Geoff Hurst hit it and it went three yards over the line! Ken Bates bought that for the NSPCC for £20,000.

At Wembley you could put an extra couple of noughts on. Teams paid £10,000 each to play on the pitch"

"At Wembley you could afford to put an extra couple of noughts on. Teams paid £10,000 each to play on the pitch. Umbro provided kit for them to take away, and a company in Birmingham made medals for everyone. We played the national anthem as they lined up before the game, then afterwards they all went up to the Royal Box and we found a lady called Janet Charlton who was a Queen Elizabeth lookalike! She had a crown and presented the medals. We did four games a day for a month. It made £1m."

There has been disappointment along the way, though. Both Stevenson and Fletcher were involved in Coventry City's move to the Ricoh Arena, only to watch with horror as the Sky Blues were later forced to groundshare with Northampton Town after a rent dispute with the stadium's owners. The League One club have since returned to the arena, although rugby club Wasps have also moved in and taken over ownership of the stadium.

"It was heartbreaking to see what happened," Fletcher says. "I got to know an awful lot of Coventry City fans and I really took it to heart. What we tried to build was a stadium that, when Coventry got back into the Premier League, would create enough money to keep them there. We achieved that, then somehow the football club lost ownership of its own stadium and it was sold to a rugby club from London."

Stadium in the sky (well, 7m up)

Fletcher is now working on projects to build a women's football stadium at a university in Philadelphia as well as an arena in Liverpool – that's Liverpool in the Australian state of New South Wales.

His other project is an intriguing one, which he believes could signal the future of football stadiums around the globe.

"I’m currently working on a fantastic stadium in Ahmedabad in India," he explains. "I’ve been working for about five years with some architects about what we call the stadium of the future. If we were to put all the good ideas and all the bad ideas into a melting pot, what would this stadium of the future look like?

"I was having a conversation with a guy from India four or five years ago, not knowing that he was listing everything I was saying. He went back to India and copied every idea I told him, and now he's building this stadium in Ahmedabad!

"The basic principle to make everything work is that the whole pitch has to lift seven metres. It gives you 250,000 square feet of space underneath the pitch

If you lift the pitch up 7m and build underneath it… that would have saved Coventry £65m”

"The complete supermarket that was built beside the Ricoh Arena would have gone right underneath the stadium. The cost saving for the supermarket if we’d done that would have been about £65m. If you can lift the pitch up then you can multi-use the underneath of the pitch and it creates so much free space for Starbucks, retail all the way round, shops, offices.

"The mistake when I look back at the Ricoh is that it works well on matchdays but it’s pretty empty through the week. There’s no community there. In India he’s got four tennis courts, three swimming pools, six badminton courts, a snooker hall, a health and fitness club, five restaurants, 200,000 square feet of retail space wrapping all the way round, you can just go on and on.

"But listen to this, what he’s not got yet is a football team to play there! He’s turned it completely on his head. What he has built is a commercial building that will pay for itself and within the next two years he’ll go and buy one of these football franchises in the Indian Super League.

"In England, you build a stadium and say, 'That’s great for football, what else can we do with it through the week?'. He's built something for the week and then once a fortnight they’ll use it for football. It’s very clever."

#FFT100STADIUMS The 100 Best Stadiums in the World: list and features here

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.