How Hillsborough changed football forever

25 years of media-fuelled metamorphosis...

Twenty-five years ago, 96 people needlessly lost their lives in the Hillsborough tragedy. The date – 15 April 1989 – will live in infamy. As Jason Cowley put it in his book The Last Game: Love, Death And Football, the tragedy was English football’s “point of no return. The culture of the game had to change definitively if football was ever to be perceived as anything more than the preserve of the white working class male, a theatre of hate and violence, of racist and misogynistic excesses, if it was to survive at all.”

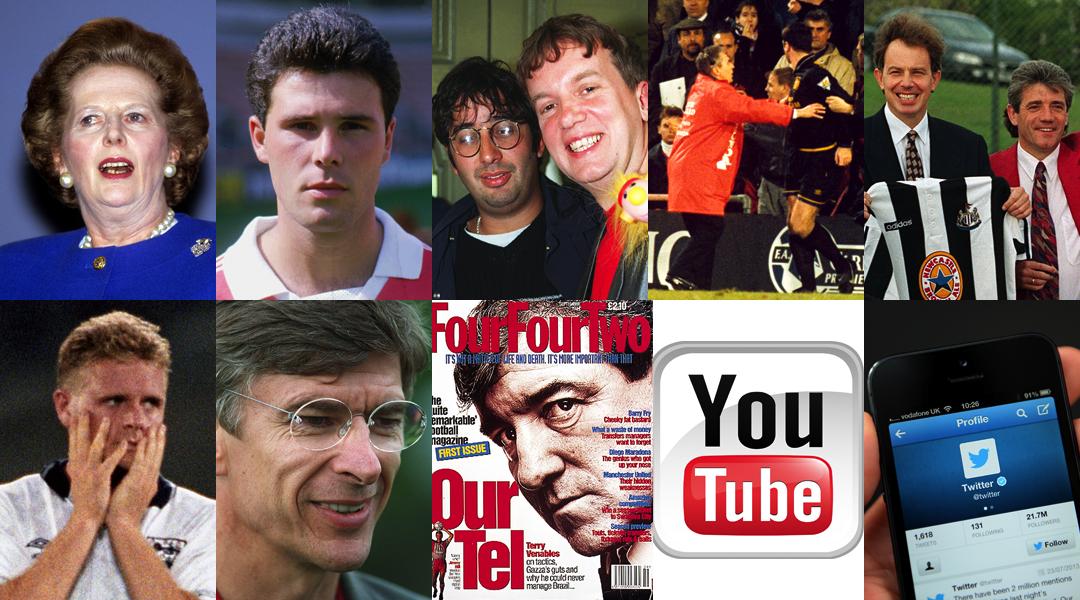

Luckily for football, it did change. Dramatically. Not even Margaret Thatcher’s government, whose attitude to football hovered uneasily between indifference and disdain, could ignore a tragedy of such scale. The inquiry into Hillsborough, the Taylor Report, was the mechanism that signalled the end of an era of decrepit, dilapidated stadiums where fans were kept in cages.

Money helped pave the way. The revenue from TV rights had already begun to soar – from £5.2million for the Football League in 1983 to £11million by 1988 – but competition between ITV, BBC, Sky, Setanta and BT has driven those revenues up to around £1billion a year for the Premier League alone.

The revamp of the old First Division was an inspired piece of commercial opportunism that has made the Premier League, to paraphrase Roy Keane, one of the best brands in the world. The advent of the Premier League and UEFA Champions League in 1992/93 gave football the kind of extreme makeover it needed to attract broadcasters, sponsors and vainglorious tycoons who fancied owning a club, ignorant of the old adage that the best way to end up with a small fortune in football was to start with a bigger one.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Football + media = popularity

In an age when footballers' salaries are routinely used in evidence against them in pub debates, it's easy to forget that the transformation of the English game wasn’t all about money. After Hillsborough, millions of armchair fans needed a reason to fall in love with football again. They found it at Italia 90. A heroic defeat against our old historical foe, the (West) Germans, and Gazza’s iconic tears helped fuel an astonishing boom in football’s popularity.

This resurgence manifested itself in all kinds of ways. The laddish football humour of Baddiel and Skinner’s Fantasy Football League TV show was suddenly ubiquitous. A quite remarkable football magazine called FourFourTwo was launched, with myself as editor, in September 1994, just after a World Cup England had failed to qualify for.

Hitherto regarded by the authorities as potential troublemakers – and largely ignored by the media – football fans were suddenly expressing themselves, airing their views on shows like BBC radio’s 606 and producing fanzines with such wondrous names as Dial M For Merthyr.

In the decades since, fans have discovered that having your opinions heard is not the same as having them count – as supporters of clubs who were nearly driven to the wall by incompetent, unscrupulous or misguided owners will testify.

Politicians began to use their football allegiance as a coded reassurance that they were on ‘our side’, a phenomenon that reached a gloriously absurd apotheosis when Tony Blair, then merely the leader of the Labour Party, picked his favourite XI. Warned that he couldn't just select Newcastle players, he chose 10 Toon legends and Andy Cole, who had recently joined Manchester United. If only he’d been as crafty at 10 Downing Street when George W Bush kept phoning, pestering him to invade Iraq...

On the pitch, the newly enriched English game was suddenly able to attract the best talent. At first, like a spendthrift winner of the new National Lottery, clubs wasted millions on Carlos Kickaballs; but in 1999, when an Arsenal manager initially known to the British press as “Arsène who?” signed Thierry Henry, the deal marked a step change in the English game’s recruitment drive.

"Paradise" lost?

Yet even as this shiny, lucrative new world was being perfected, there was a nagging sense that something had been, or was being, lost.

For a start, the time-honoured process that wed many of us to our team – watching them week in, week out, for better for worse, in sickness and in health, etc – was being eroded.

If you're lucky enough to support a successful team today, you might not have the wherewithal or opportunity to watch them every week. Allegiance has had to be cemented – and expressed – in different ways: in fan forums or on Twitter (where we cathartically release our frustration with invective disguised as analysis), in managing your team on FIFA 14 or sneakily watching the action live, illegally, on the internet. One of the bizarre paradoxes of the football boom of the last 25 years is that for a generation of fans, the game is, primarily, something they watch on TV.

Then there was the undeniable fact that football had gone – I can think of no other way to put this – a bit bonkers. Gazza’s tears weren’t the only notable aspect of Italia 90. That was the first World Cup where the “rotters” – as the football hack pack referred to their colleagues who filled the front pages with any ugly, vaguely plausible nonsense loosely connected to the beautiful game – ran amok.

Exposés about footballers – how much they drank, how many times a night they had sex with a page three girl, how much they lost on the horses – became an industrial commodity. It is easy to blame the tabloids – and we should – but we’re guilty too. Would the papers print this tosh if we didn’t read it?

By 1995, the industrialised hype had begun to warp the game, a process symbolised by the Premier League’s “where were you when they shot JFK?” moment: Eric Cantona’s kung fu kick at Crystal Palace.

What is fascinating, in retrospect, is the reaction to Cantona’s attack. Although there was a consensus that, whatever the provocation, Eric had gone a bit too far this time, the incident made him a hero. This was football’s equivalent of the rock star trashing a hotel room, yet so astonishing and unprecedented it was hard to see how even the demented genius of Ozzy Osbourne could have surpassed it.

Jonathan Pearce’s radio commentary of the kick on Capital Gold – even now, when I listen to the clip, I still fear his larynx is about to explode – is as fondly recalled by fans of a certain age as Kenneth Wolstenholme’s “They think it’s all over”. At the end of that epic season, we finished our FourFourTwo review of the campaign with one word: “Fish”.

Football becomes everything

It seemed a fitting final word on a season that had become frankly surreal. The game has stayed surreal – we hardly notice now because we’ve simply got used to it.

In the 1970s and 1980s, millions of young men expressed their identity through rock music. The respective merits of different bands – the Jim Morrison vs David Bowie debate rumbled throughout my university years – were a reliable conversational standby, water-cooler conversation before most of us knew what a water cooler was.

At some point, that changed. Not sure why. There seemed to be so many genres and microgenres and so few acts – after U2 and Oasis – that transcended those boundaries that it became much easier, if you wanted to strike up a conversation around that proverbial water cooler, to discuss football.

Because the game is now inescapably everywhere – on TV, in the papers, in glossy men’s mags, on YouTube – it is almost impossible not to have an opinion on such weighty matters as the coaching qualities of David Moyes, whether Sergio Agüero or Luis Suárez has the better technique or which Bond villain Cardiff City’s ridiculous new owner most resembles.

Looking back, it’s astonishing how much has changed. In 1989, nobody talked about the magic of the FA Cup because the fact that it had magic was just a given. You could go through an entire season without hearing a single reference to the “fit and proper test”. None of us had heard of a journeyman Belgian midfielder called Jean-Marc Bosman whose thwarted ambition to join Dunkerque would revolutionise the selling and buying of players. And 25 years ago, it was impossible to be instantly informed that Polish football coach Michal Probierz was experiencing an unhappy return to Bialystok – as I was the other night on Twitter.

As long ago as 1995, the splendid Half Man Half Biscuit charted the perils that lay ahead for football – and us. In the masterly Friday Night And The Gates Are Low, they sang: “Stick a burger in my mouth/Shove a seat beneath my arse”. The poignancy of their lament is that they’re standing in the rain, watching their team, complaining that a “bastard slip of a sub” has ruined their weekend, yet ruefully admitting they can think of nothing better to do.

We’ve all been there, and 19 years after that sublime riff on Dancing Queen, we’re still there: complaining, probably not quite as wet the fans in the song, yet still with nothing we’d rather do.