This is how it feels to be City: The 30 years of hurt and the 15 years that followed

Fifteen years on from the famous Division Two play-off final win over Gillingham, City fan Simon Curtis explains how the fans haven't changed, even if everything else has...

Around the end of the last century, you could read a surprising amount about Manchester City. I kept the cuttings just for the sheer, abysmal masochism of it all. It was less a time of false dawn and more one of Apocalypse Now.

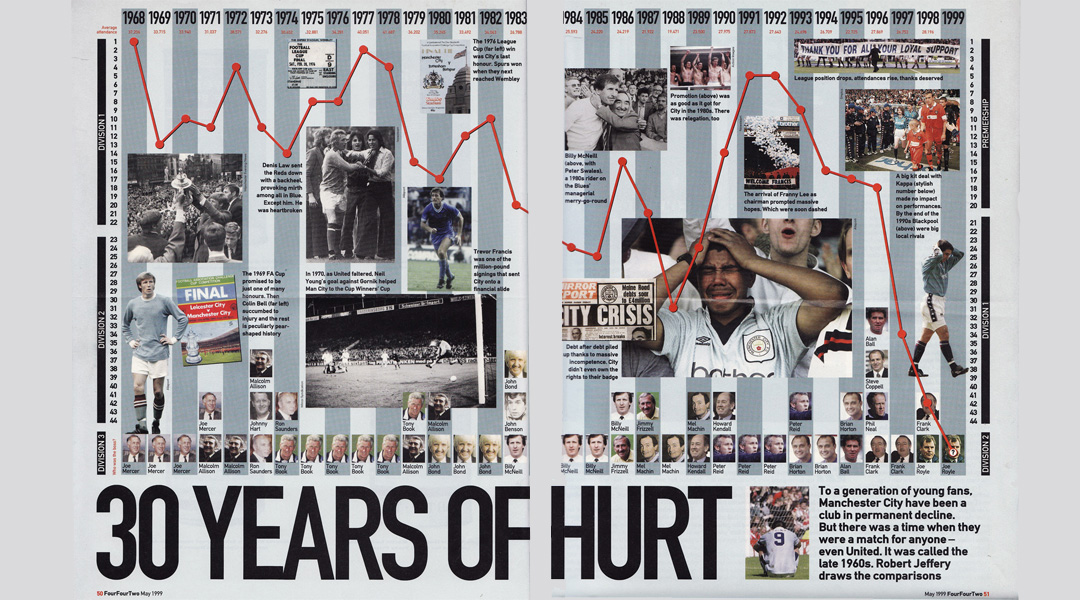

Bill Borrows had been commissioned to write a piece for Loaded, which carried the simple title “The Fall and Rise of Manchester City”; In Arena magazine Paul Morley had penned a wonderfully satanic piece called “City of Lost Souls”, while FourFourTwo carried a five-page Robert Jeffrey splash on “30 years of Hurt” - the opening spread is pictured above.

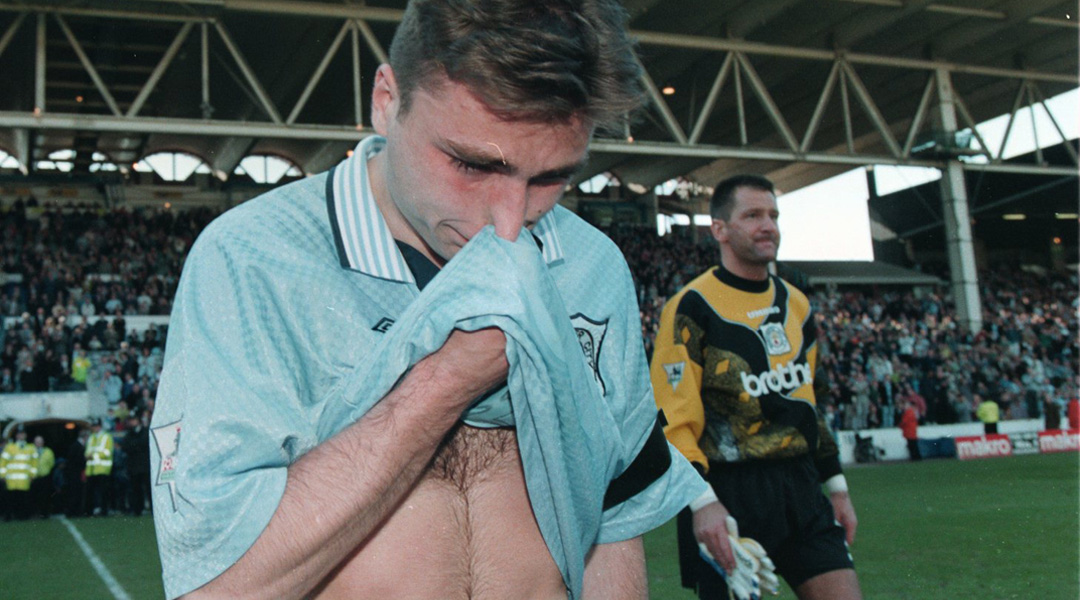

To complete the set, GQ magazine (disaster and turmoil brings you a wide range of interested parties) carried an article entitled “It’s Been Emotional”, with a spread of pictures showing players, fans and administrators in a state of considerable flux. They were all in tears, every last one of them; from Gio Kinkladze to that chubby kid on the terraces at Stoke the day City went down to the third tier. The rest of us were not far behind. In tears, in turmoil, in denial.

As Manchester United marched to the European crown with that never-to-be-forgotten night in Barcelona that still makes Clive Tyldesley get up in the night for a cup of water and a sheet or two of toilet paper, City were heading for Rotherham and Bury and preparing for a blizzard of insults and a gale of laughter wherever they went. To top the lot, The Times had Mark Hodkinson trail behind us through those third division grounds, writing a weekly column that later appeared as a book, “Down Among The Dead Men With Manchester City”. The wonderful imagery of Manchester City and its bedraggled fans traipsing into the Racecourse Ground and asking the way to Bootham Crescent was a story not to be missed.

Heather, toasters and bananas

From the Glory Days of Malcolm Allison and Joe Mercer, to the beginnings of a concert hall joke with Eddie Large on the subtitute’s bench, we had never seen anything like this. An idiosyncratic club to be sure. Helen Turner, a flower seller outside Manchester Royal Infirmary, would sit in the front rows of the North Stand and offer Joe Corrigan a sprig of lucky heather before every game and then thunder her bell every time City won a corner. In 1978 the club bought Kaziu Deyna, the Polish World Cup captain, for a consignment of toasters and fridges, a deal arranged by electircal goods magnate and megalomaniac chairman Peter Swales. Someone stumbled onto the away terrace at West Brom with an inflatable banana and, within weeks, there were thousands of the things, joined by paddling pools, crocodiles and fried eggs, cramming every City game. It was a club with a heart and a sense of humour, which was often turned on itself for good measure.

But, by 1998, we didn't need the self-deprecating jokes and stories - everyone else had learned to do it better. Manchester City, English League Champions in 1968, proud European trophy winners in 1970, were in the third division and staring at a triple-X fixture list, whose first few weeks offered us the delights of Wrexham, Chesterfield and Northampton.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Cup defeats to the likes of Shrewsbury and Halifax in the good old days had raised a laugh and helped cement City’s professional profile as a maverick, drop-dead-funny club, but this was different. This was cry-your-eyes-out sad. It felt a little like death creeping near and raking its nails down your back. The money had been frittered away. The best players had been sold. The ground looked tired and delapidated. The fans, morose and sick to the back teeth of incompetent adminstrators and awful players, were flat on the floor.

Then a strange thing happened.

As the new season’s fixtures crept closer, an upswell of bugger-them-all support began to flood around the old precincts. By the time City took to the field for serious third division combat, season ticket sales had gone past the previous year’s figure in Division Two. As the City players walked out on a bright and sunny Saturday 8th August 1998, 32,134 cheering fans were waiting to greet them.

It would prove to be just enough, as City – refusing to pull up any trees even in these desperate circumstances – averaged more than 28,000 throughout a season, which would end at Wembley for an unforgettable climax infront of 40,000 Blues fans against Tony Pulis’s Gillingham. It seems strange to think that this all happened relatively recently. We flocked in our thousands to Wycombe and Walsall, To Bristol Rovers and Colchester, to cheer on the likes of Craig Russell, the flimsy Gary Mason (later to star for Dunfermline) and the even-then heavy-legged Jamie Pollock. These threadbare offerings were all we had, but it was our City and we weren’t going to give up a habit of a lifetime, just because they were absolutely rubbish.

There were times when giving up might have been the wisest thing to do. FourFourTwo published a gatefold colour picture featuring the large, half exposed backside of a well-proportioned City fan hauling himself up the fencing on the spartan away end at Macclesfield, City’s local derby for the season (Bury and Stockport were a division above). The ground stretching out infront of the City supporters was so low, so unassuming, it might have belonged to Sunday League. And yet here we all were, with the bravado of the inebriated shouting our heads off for Shaun Goater and Paul Dickov. Football fans the length and breadth of the country thought we were mad and they were probably right.

That season ended in a triumph of kinds, if you can call a penalty shoot out success against Gillingham a triumph. It was followed by another promotion, under Joe Royle, straight into the Premier League, producing another rash of articles on the resurrection of City from joke to would-be big hitters once again. But this, naturally enough, was anathema to a club brought up on the legends of its own slapstick existence. Down we went again, only for Kevin Keegan to ship up in Moss Side promising us the earth. Instead we got Ali Bernbia and Eyal Berkovic, a continuation of a rich history of sumptuous attacking football and yet another promotion.

Now, if you are following this, even if you are a committed Blue, the sheer number of ups and downs will have started to produce a kind of sickly dizziness. I know, I saw each one, counted them all and was ill after most of them. Lay them all down alongside each other and you will have enough comings and goings to enact your very own Ealing Comedy. And comedy it was. None of us knew whether we were coming or going, sticking or twisting, laughing or crying. To the backdrop of Champagne Supernova, City had become a laughing stock, a cult and a hill of confusion all run into one.

Scroll forward through the enforced ownership of a Thai dictator and the surpise arrival of the biggest football investment in the history of the game and you will see the same faces as before, with the addition of a few shiny new ones, attracted by the smells and glitter of the new era at City. Those old faces, stretched now with wide grins and glassy-eyed expressions of “we’re not really here” have faced the driving rain of relegation with the same spirit they now bask in the warm glow of Premier League title success number two, of two domestic trophies in the same season, of the splenour and magnificence of Yaya Touré and David Silva, of Sergio Aguero and the rock that is Vincent Kompany. And, yet still we all laugh at ourselves, at our grand stroke of luck, at the never-to-be-forgotten trip we have all been on, at the beauty of Martin Demichelis running full pelt with the Premier League trophy, at the sheer bloody nonsense of the last thirty-odd years.

We now find ourselves in a state of considerable flux. We, who have trod the boards at Darlington and felt the soft mud of Macclesfield under our feet, are still not sure if this is meant to be. All these wins, all these goals, all these people who admire us from foreign fields, and all those closer to home who now hate what we have become. It never used to be like this, in the cosy days of failure and flotsam, of Andy Morrison and Craig Russell. In the days when Tony Book’s flares whipped in the wind like all our lost hopes, when the buzz was about Garry Flitcroft’s bob and Nigel Gleghorn’s goalkeeping gloves. When there was nothing else but Liam Gallagher and Richard Jobson.

The easy option?

No longer do we straddle the high moral steps of constant, dismal failure. Kun Aguero, Yaya and the little magician Silva have seen to that. All that dashed, squashed hope has been replaced by giddy emotion. The howls of indignation are no longer ours but now seep towards us from Islington and Nyon, Salford and Munich. To support City in the olden days was “to believe that God might have trouble running things on this planet”, wrote Paul Morley in 1998. “It is to accept with heroic willingness the dreadful flat fact that the universe is cold and hostile and that nothing good will come of it. To tackle head on the crushing pointlessness of existence and to attempt to make something of it. Why do it? Because somehow it seems more dignified and fulfilling than taking the easy way out and supporting Manchester United....”

So what do we do with our gallows humour and our belted songs of attrition now that City have become one of those dreaded easy teams to support? How do we hold on to that magical keep-going-and-be-damned attitude that saw us through disaster after disaster when now we inhabit a land of milk and honey that not one lost soul from the Kippax could have imagined? Manchester City the title holders. Manchester City the Abu Dhabi Royal Family’s team. Manchester City the Champions League regulars. Manchester City this and Manchester City that.

The glittering football, delivered by a squad of global superstars (and Jack Rodwell), the pristine pitch, the flashlights, the screams of tourists, the prestigious visitors, the friendship scarves with Barcelona and Real Madrid. A scarf, half Real half City! Half Barcelona (we may call them Barça with time) half City. What a thing is this? What of our cheap ski hats in 1983? Sat forlornly over our Morrissey quiffs and our Bunnymen side burns, our half-Rangers-half-City tributes to tribal nothingness. Where are they now in this maelstrom of Champions League brick-a-brac?

Instead, we nod to the past as best we can. We stand upright in the present and open our wallets towards the future. Silently, guiltily, we know the truth. There is no going back. What once was can never be again. For now we must embrace the new era, the dawn of prawn, the sun-up over SportCity, the ever-lasting glow of the wealthy, the healthy. The stark light gleaming off the glass sides of our blue-chip sponsored ground reflects beaming faces, painted musicians and hand held mics. People jump up and down with their backs to the action where once we leant forward and covered our eyes from the gales of oblivion. Where dread and fear stalked, a Mancunian version of proud self-belief now jostles for position. No slinking out at Wolves, no peering down alleyways at Huddersfield, no shirking the second half at Grimsby, just frothy glasses of Mahou, freshly fried calamares and a fridge magnet of the Bernabeu.

Manchester City, the new vastly improved Manchester City, may bear little resemblance to what went before, but those wizened, cracked old faces remain as a stark reminder of who we were and who we are. A club with wonky DNA and a set of extraordinary followers who have been and still are willfully, whimsically, stubbornly, recklessly, heart-warmingly blue through and through.

This is how it feels to be City, the song goes. You signed Phil Jones, we signed Kun Aguero. Well, this is also how it felt to be City and they can never take that away from those who have waited forty years to feel the sunshine on their faces.