How Manchester United vs Juventus became the Champions League's first great rivalry

The two clubs clash for the first time in 16 years at Old Trafford on Tuesday, rekindling a thrilling old match-up which helped shape Alex Ferguson's historic Treble winners

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

“Juventus have qualified?” asks a sweaty Gary Neville. The right-back is in the middle of an ITV interview following Manchester United’s 1-1 draw with Bayern Munich at Old Trafford in December 1998. Word filters through and Neville is informed that, yes, Juve have qualified – implausibly – for the knockout rounds after picking up their first victory in Group B against Rosenborg... on the final day.

Neville’s reaction is priceless; his face contorts into impending dread, like a man who’s just looked down from a very great height and wishes he hadn’t.

But this was indicative of the universal fear that Juve instilled in opponents across Europe. They were serial Champions League finalists by this point, and despite losing two of those showdowns, Marcello Lippi’s team were considered the measuring stick of late-90s European football. Beating them almost equated to winning the trophy.

As such, Juventus vs Manchester United became the Champions League’s first continental rivalry: a team of battle-hardened winners against Alex Ferguson’s precocious fledglings. The two sides met for three consecutive seasons, culminating in the classic semi-final of April 1999.

“Juventus were the model for my Manchester United,” Fergie admitted. It became a master-and-student dynamic, with Ferguson grasping – through his battles with Lippi – what was needed to succeed at the highest level. The series of matches would mould United into European champions, and later win Ferguson a knighthood.

Europe: the early years

In the years after the Heysel ban, English football found itself hopelessly adrift in European competition.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

United had capitulated with relative ease in the Champions League. In their first attempt in 1993/94, they exited in the second round to Galatasaray on away goals. Their performance was so bad that Guardian journalist David Lacey said they “made a poor case for belonging to anybody’s league of champions”.

A year later they returned, drawn in a group with IFK Goteborg and Barcelona. Performances improved, albeit only marginally. United didn’t lose at home, but their naivety away from Old Trafford was woefully exposed.

At the Camp Nou, without the suspended Eric Cantona (serving a four-game suspension for insulting Swiss referee Kurt Rothlisberger in the Galatasaray fiasco), United were torn to shreds by the brilliant Romario-Hristo Stoichkov axis. The pair toyed with the hapless Steve Bruce and Gary Pallister in a dominant 4-0 win. Three weeks later, they lost to surprise group winners Goteborg 3-1 in Sweden and were eliminated.

The first games

After Juventus and United were paired together in Group C for the 1996/97 edition, the latter travelled to a brutally cold and cavernous Stadio delle Alpi in September 1996. Juve were reigning Champions League holders and looked every bit the dominant force.

“I stood in the tunnel before kick-off and the Juventus players made ours look small,” remarked Ferguson. It was men against babes. “Just standing in the tunnel next to them was intimidating,” Neville wrote in his autobiography Red. “Big names, big players, in every respect.”

The one-goal defeat seriously flattered United. “It could have been 10-0. It was the biggest battering I’ve ever had on a football pitch,” said Neville. United didn’t register a single shot on goal in the 90 minutes – according to Neville, the only time it happened in his 602 games.

The return match in November followed much the same pattern. While Juve weren’t as dominant as they had been in Turin, they were never genuinely under threat despite a raucous atmosphere inside Old Trafford. United hit the bar through David May and Cantona, but huffed and puffed against the Italians’ well-marshalled defence. Alessandro Del Piero’s penalty secured another 1-0 win after the man himself was brought down by Nicky Butt.

United’s early Champions League jaunts had been impeded by the draconian three-foreigner rule. Irish players also fell into this category, and thus Ferguson’s sides felt incomplete. With the Bosman ruling and abolition of the limit in late 1995, they had been simply overawed in their dealings with Juve; a team too streetwise, too tactically savvy and too powerful to fall for Ferguson’s gung-ho, cavalier brand of football.

Cantona in particular had shown his limitations as a footballer. He was remarkably off the pace in both games, and in the latter wasted two glaring chances. Despite being a standout performer in the early years of the Premier League, he was routinely found wanting in Europe. Here, the Frenchman was always on the periphery of the action, outclassed by a young Zinedine Zidane and, fittingly, dominated by the most famous of alleged water carriers, Didier Deschamps.

The road to Barcelona

Ferguson, a man never easily impressed, became enamoured with Lippi during their initial tussles. The Italian’s aura, his ability to exude calm even in the biggest of games, enthralled the Scot.

In a 2009 interview, Ferguson recalled: “I remember being in Turin and Signor Lippi was on the bench – wearing a leather coat and smoking a small cigar, smooth and calm, while I was a worker in a tracksuit being drowned in the pouring rain.”

The pair struck up a friendship based on mutual respect. Lippi couldn’t speak English and Ferguson’s Italian was limited, so French – and wine – became the lingua franca of choice. Ferguson had his players watch videos of Lippi’s Juve, telling them: “Don’t look at the tactics or technique, because we have that too – you need to learn to have that desire to win.”

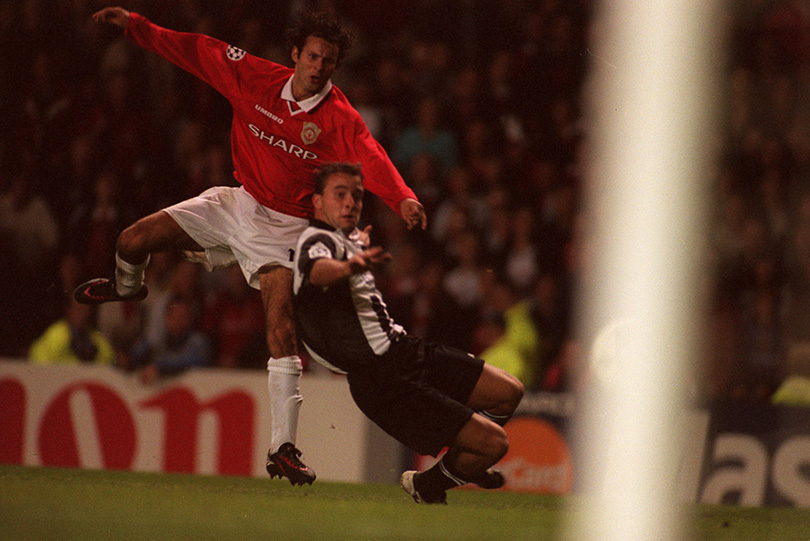

And win they would. Drawn in the same group again in 1997/98, United emerged victorious in a barnstormer at Old Trafford that October, winning 3-2 thanks to a wonderful Ryan Giggs strike. “It was a measure of how far we’ve come,” beamed Fergie.

If the United-Juve clashes were a film, the first act was a scene-setter demonstrating the long road ahead for United; the second was them getting to grips with the measure of the beast; the third an epic crescendo where they finally slayed it.

This time, Ferguson and United felt ready. They’d knocked the Inter of Ronaldo, Roberto Baggio and Diego Simeone out in the quarter-finals – their first-ever elimination of an Italian team.

The first leg against Juventus at Old Trafford ended in a 1-1 draw, setting up what was arguably the greatest semi-final second leg in the tournament’s history.

Ferguson’s pre-match assertion that the Old Lady – now without the recently departed Lippi – would try to kill the tie inside the opening 20 minutes proved prophetic. United were 2-0 down by the 11th minute, with Pippo Inzaghi scoring two typically Inzaghi-like goals – one predatory, the other fortunate.

“Everyone wrote us off because nobody went to Juventus and won,” said left-back Dennis Irwin. They hadn’t lost at home in a European knockout tie for five years, and not to English opposition since 1980. History was against United, and now the odds looked insurmountable.

Enter Roy

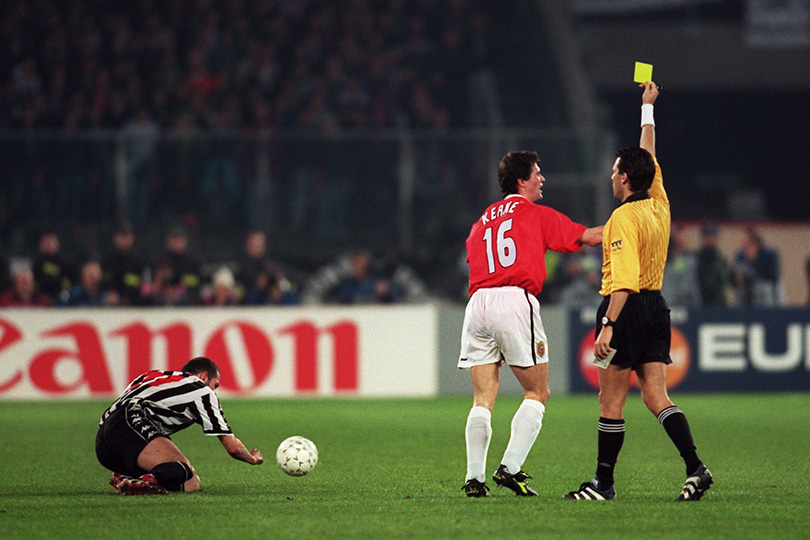

“A captain’s goal by Roy Keane!” Clive Tyldesley bellowed on commentary. The Irishman is synonymous with this game. It is generally regarded as his zenith as a footballer, yet before and after his floating header had given United real hope of a comeback in the 24th minute, Keane’s performance was hardly one that justified folklore status. The legendary second yellow card arose after his failure to control a relatively straightforward pass from Jesper Blomqvist.

It wasn’t until the second half that he gave the ‘Roy Keane performance’. In technical terms the central midfielders gave better performances, but not in these most testing of conditions: his sheer drive and refusal to admit defeat was the greatest influence. “Roy was unbelievable,” said Paul Scholes. “When he got the goal, it really galvanised us,” added Andy Cole. The unheralded Ronny Johnsen and Nicky Butt gave equally stellar performances, pressing Juve’s midfield and disrupting the flow of Zidane, Edgar Davids and Antonio Conte.

Ten minutes after Keane’s goal, Dwight Yorke equalised. Conte had a header cleared off the line by Jaap Stam. Yorke then hit a post. A cagey, tight affair it was not.

The intensity was searing, and didn’t let up in the second half: Irwin went on a marauding run and hit a post, Inzaghi had a goal chalked for offside and forced a good save from Peter Schmeichel, Zidane probed, Keane and Davids battled, and Cole should have scored from a typically brilliant David Beckham cross.

ANALYSIS How Cristiano Ronaldo has already changed Juventus

REMEMBERED Henrik Larsson at Manchester United: how a 10-week loanee made a major impact at Old Trafford

Seven minutes before full-time, Cole and Yorke – who’d destroyed Ciro Ferrara and Mark Iuliano in the first half through their movement and telepathic understanding – combined for the killer blow. Yorke bundled his way past Ferrara and Paolo Montero, and Cole followed up after Angelo Peruzzi had brought Yorke down to slot the ball home.

It was United’s first victory on Italian soil, and their inferiority complex against Juve had finally been shattered. The fledglings were now soaring. The home fans, knowing the superior team won, applauded United off the pitch. For the first time since 1991 would there be a European Cup final without the presence of a side from Serie A. It was the end of a dynasty.

When Neville had his testimonial in May 2011, he choose Juve as his farewell opposition. Some things just stick with you.

Emmet Gates is a freelance football journalist with work published across a multitude of websites and magazines. Writing for FFT since 2016, Emmet is a disciple of the Gazzetta Football Italia years and remains a Serie A advocate. He also worships at the altar of Diego Maradona and collects '90s Serie A shirts, now a very expensive hobby.

Join The Club

Join The Club