How missing the boat created Georgia’s best footballer

The story of Boris Paichadze, Georgia's finest footballer of the 20th century

The telegram was succinct. “Your father is at death’s door: come home”.

Boris Paichadze had been due to set sail the following day. His tanker at the port city of Batumi, the Metalist, was bound for Britain, but he immediately caught the train home. He arrived at midnight, only to discover his father Solomon was in fact alive and well. What’s more, the family knew nothing of any telegram.

Instead, his local side were the ones gurgling out a death rattle. It wasn't until many years later that a teammate at Poti, Kako Imnadze, revealed that he had actually sent the message in an attempt to get their former centre-forward back home for a crucial game.

Boris initially refused to play. He had, after all, been away for some time, but his father eventually changed his mind and Boris ended up scoring both goals as Poti beat Batumi 2-1.

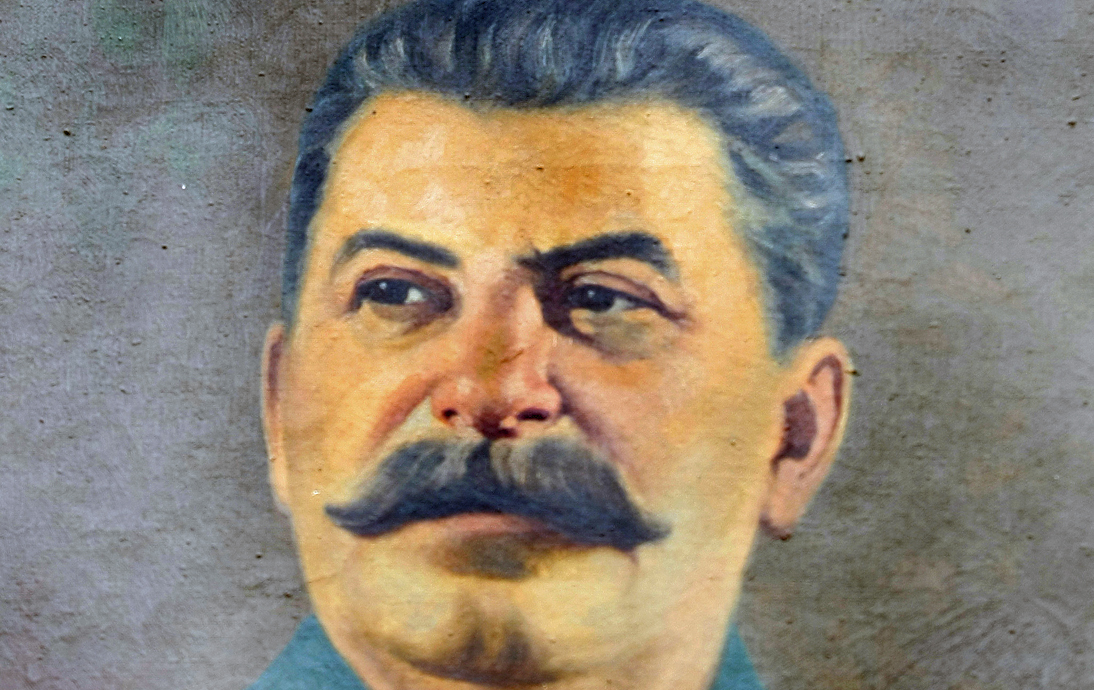

In effect the deceptive missive helped launch his career; Boris would go on to become the best player Georgia has ever produced, but it is also no exaggeration to say that the telegram perhaps saved his life. This was Stalin’s Soviet Union and many of the sailors who travelled to the west would later find themselves interned in labour camps under Article 58.

One of six children, Boris Solomonovich Paichadze was born in Onchiketi, a small village just outside Chokhatauri, a town in western Georgia about 130 miles from the capital Tbilisi (or Tiflis, as the city was known at the time) on 3 February 1915. His father worked as a foreman down at the docks in Poti, the country’s main port, and it was there that a young Paichadze first discovered football after becoming fascinated by the ad-hoc matches between British sailors on the waterfront; father Solomon also played informal games with his fellow workers.

Paichadze’s own steps into football began with the city’s side as a 16-year-old. Even in his youth he stood out as a tremendously skilled and prolific striker, and soon garnered a popularity among rivals and referees alike: opponents refrained from roughing him up during matches. It is said that in one game a defender ignored the pleadings of his team-mates and fouled Paichadze relentlessly - so Paichadze clattered into him, causing the player to limp off the pitch. The referee turned a blind eye to the incident.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Yet it was not football, but the sea, that was his initial calling. A keen student, after graduating from school he attended a marine college and eventually wound up working as a mechanic on a ship which plied a route between Batumi and the Ukrainian port of Odesa. It was from Batumi that he sought passage to Britain until fate decreed otherwise. The Metalist left for Britain without him.

Upon his return home, Paichadze picked up football again and in 1935 joined Poti on a lengthy tour of the Ukraine, mainly to Donbas, an industrial region in the republic’s east. Each mine had its own team and although the standard of football was good, Poti won 28 of their matches and drew the other. By now the 17-year-old was gaining quite a reputation for himself.

A week after returning home from the Ukraine, Paichadze and several of his teammates received an invitation to enrol at the Transcaucasian Industrial Institute in Tbilisi without needing to pass the necessary entrance exams. This was mainly because the dean, Ivan Vashakmadze, was an avid football fan. That year its team won the college championship and each player was awarded a bicycle for his efforts.

In 1936, a pan-Soviet football championship was established. Dinamo Tbilisi (Tiflis), founded nine years earlier as part of the Dinamo Sports Society, a body affiliated to the Ministry of the Interior, cobbled together a side for the inaugural competition.

Head of the NKVD in Moscow – a forerunner of the feared KGB – was Lavrenty Beria, himself a Georgian and something of a football fanatic to boot. Described as a “crude and dirty left-half” in his day by the Spartak Moscow founder Nikolai Starostin, Beria was a Dinamo fan and it is alleged used his influence to their benefit.

He wanted the 21-year-old to join Dinamo, much to the dismay of Vashakmadze, who was angered by the decision.

But Boris had little choice. By this time, Paichadze's father was in the gulag – possibly relating to an incident 30 years earlier when he attempted to thwart soldiers suppressing a strike at the port which saw him imprisoned for a month – and Paichadze had been promised his release if he signed.

It didn't work out that way. It took him five years to discover that Solomon was an inmate at the Koltas camp. Boris sent the money for his father to return home, only for the Germany invasion to halt any further contact. His teammates warned Paichadze not to press the issue, fearing the consequences, but in 1942 he relented and sought a meeting with Beria. It was at this stage that Paichadze discovered Solomon had died.

Boris was a one-club man, spending 16 years with Dinamo in a career truncated by the war. A quick and skilled dribbler with an eye for goal, he led the line but often dropped deep and roamed about the pitch, which confused opponents. He made his debut in 1936 and scored 68 goals in 110 matches before World War Two halted Soviet football.

He was the wrong side of 30 when the championship resumed, but still netted a further 41 times. Perhaps the only thing missing was a trophy. Twice he was a silver medallist and on four occasions Dinamo finished with the bronze, but he had long since retired when the club finally won the league in 1964. A knee injury sustained against Torpedo Moscow ultimately curtailed his career by the age of 36.

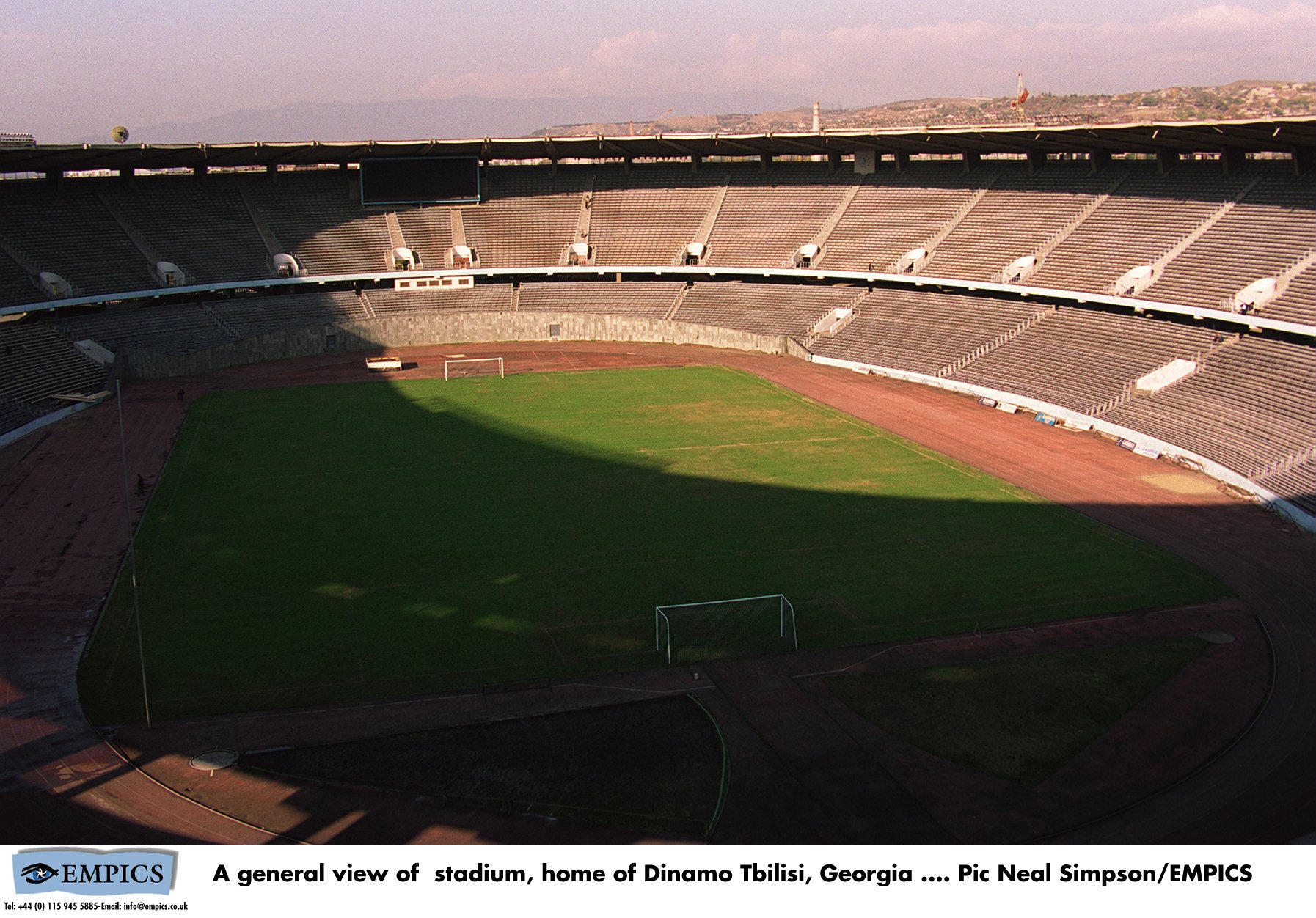

Initially he did not want to coach, but was persuaded to work with Dinamo for a couple of years before taking up a role at the national stadium in Tbilisi that now bears his name, for a time working with the Georgian Football Federation.

Paichadze was married to his wife Margot for over 50 years and had two sons, Otari and Ramaz, but died on 9 October 1990, aged 75. In 2001 his peers voted him as the best Georgian player of the 20th century. Perhaps sometimes it's better to miss the boat.