How the nature of English captaincy has changed - and in contrast to events in the outside world

Times they are a changin', writes Alex Hess, who explains the remodelled role of the Premier League skipper with reference to other forms of leadership…

It seems like an appropriate week to discuss the nature of leadership. Because as well as the pivotal and horrifying changes in the nature of political command hammered home by recent events – of which more on shortly – there's also a quieter and altogether less horrifying change occurring in English football around the same theme.

It’s a faintly remarkable fact that four of the Premier League’s 'big six' clubs currently have captains who can’t get in the team. Wayne Rooney at Manchester United, Vincent Kompany at Manchester City and John Terry at Chelsea have all been dropped from their manager’s first XI in no uncertain terms. At Arsenal, Per Mertesacker’s knee injury has seen Shkodran Mustafi come into the team and excel, meaning Mertesacker can expect a place on the bench when he’s fit again.

In the first three instances, the player's captaincy hasn't been seen as a reason for automatic selection. Indeed, in the cases of Terry and Rooney, their managers have had to actively extinguish the cult of personality that's existed around them for years. It says much about English football, and England in general, that the decision to omit these two warrior-leaders was initially reported as shocking and headline-worthy despite the fact they were patently not worth their place and hadn’t been for some time.

Less blood, less thunder

It's a marked shift from 12 years ago, when the captains of the Premier League’s top six were British-style leaders in the most bone-crunchingly orthodox sense

For as long as it's existed, English football has expected its captains not only to be present on the pitch, but to provide the sort of tub-thumping, all-action brand of leadership that made icons of Terry Butcher and Bryan Robson (as well as Terry and Rooney): barked orders, clenched fists and conspicuous displays of physical bravery have been the hallmarks of the English skipper, who would automatically be his team’s centrepiece and driving force. But times are changing.

Of the other two members of England’s top six, Tottenham Hotspur’s captain is Hugo Lloris, a quiet, calming presence and a goalkeeper, neither of which conform to the conventions of the English skipper. At Liverpool, Jordan Henderson has only recently begun to convince as a successor to Steven Gerrard (the ultimate action-hero captain), having stopped attempting to impersonate his predecessor and instead allowed his own, more understated style of leadership take its course.

It's a marked shift from 12 years ago, when the captains of the Premier League’s top six were Patrick Vieira, Terry, Roy Keane, Gerrard, Alan Shearer and Olof Melberg, a sextet that, with the possible exclusion of the latter, were British-style leaders in the most bone-crunchingly orthodox sense.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Gerrard, in his autobiography, describes being in the dressing room ahead of his England debut in 2000: “As kick-off approached, battle-cries began. Shout after shout. This is England. Our country. Don’t miss a tackle. F***ing deliver. In the middle of the dressing room stood Tony Adams and Alan Shearer, whipping up the storm. Shearer was screaming at his fellow soldiers like a warrior preparing for combat. Adams was going round the room bawling at players indivudally. He fixed me with a stare and spat a question in my face: ‘Are you f***ing ready for this?’”

Qualities valued differently

This is in stark contrast to public life, where rabble-rousing and conspicuous aggression are not only in vogue but seemingly function as a shortcut to mass approval

Fifteen years ago, that was the default mode of leadership in English football; these days, though, it's different. A more considered brand of leadership is now valued above the rabble-rousing and conspicuous aggression of years past.

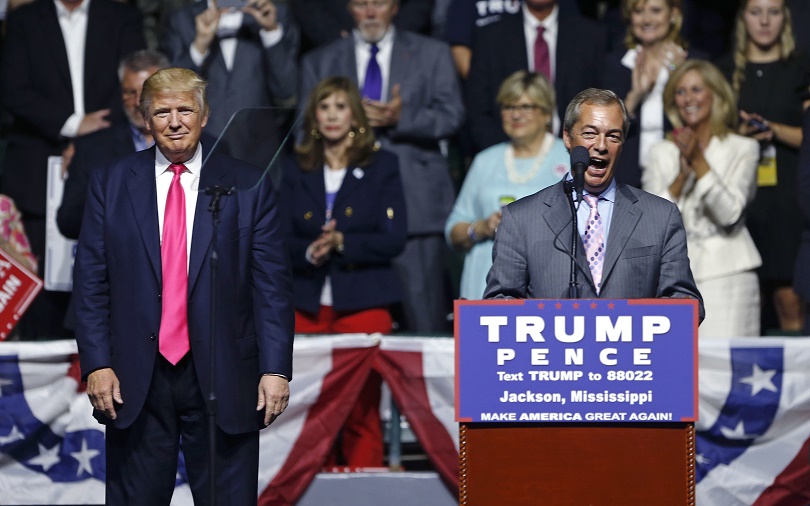

This is in stark contrast to public life, where rabble-rousing and conspicuous aggression are not only in vogue but seemingly function as a shortcut to mass approval, as shown with such nightmarish conviction by the EU referendum and US elections this year, in which victories were secured by the open hostility of Donald Trump and Nigel Farage, hateful men who epitomise the notion of a personality cult.

At this point it’s worth noting that Premier League football is a British institution that actively embraces foreigners – something that's neither common nor fashionable in this country in 2016. Indeed, all of the top six clubs are managed by foreigners, and it’s no coincidence that the division’s coming generation coaches – Jurgen Klopp, Antonio Conte, Mauricio Pochettino and Pep Guardiola – preach a playing style which elevates togetherness and collectivism above all else, at times sacrificing star players like Daniel Sturridge and Sergio Aguero in the process. Collectively, it was their decision to make a departure from the blood, sweat and tears, personality-cult captaincies of Terry and co., and towards a model where the identity of the armband-wearer assumes far less importance.

We could read this as yet another cherished tradition of British life being snatched away by foreign insurgents: Conte and his like coming over here, laying waste to the time-honoured pride of the armband and even collecting a thievingly generous wage in the process.

Less significant

What would Fergie do? 7 big changes Sir Alex would make at Man United today

Klopp's chaos theory lacks control: Why Liverpool won't win the Premier League

On the other hand, we could simply observe correlation at work between immigration, collectivism, thoughtful leadership – and success. After all, the above four coaches have won 19 major trophies between them. Throw Arsene Wenger and Jose Mourinho into the mix and that total rises to 48.

Similarly, we could also note the way the frenzied, tub-thumping brand of leadership tends to align itself not only with xenophobia and isolationism, but also with catastrophic failure: the England side’s international woes are the stuff of legend; Britain’s departure from the EU is predicted to be calamitous; and while we don't yet know what a Trump presidency will bring, few are expecting a reign of altruism and inclusivity.

So when England take to the pitch to play Scotland on Friday and the TV commentators’ discussion inevitably turns to the identity of the captain, the appropriate response is probably “Who cares?” – and not just because there are more important things to worry about right now.