How Pellegrini & Co. are showing Europe what they've been missing in the dugout

Martin Mazur on why South American bosses are finally making inroads in Europe...

For decades, European fans have enjoyed the quality and versatility of South American players. Moving to Europe not only became a way to earn more money; it was also a dream and a matter of pride - the natural step in every footballer’s professional career. But when it came to managers, the situation was completely different.

For one reason or another, the mighty managers that had acquired a big reputation in their homeland (sometimes even bigger than the statues fans erected after them), couldn’t take their winning mentality across the Atlantic. Either they simply weren’t called or, worse, were appointed but were sacked shortly afterwards.

It’s only in recent years that this situation is starting to change, thanks to the progress and success of Chile's Manuel Pellegrini (Villarreal, Real Madrid, Getafe and Manchester City), Argentina's Marcelo Bielsa (Athletic Bilbao), Diego Simeone (Atlético Madrid), Mauricio Pochettino (Espanyol, Southampton), Juan Antonio Pizzi (Valencia) and Uruguayan Gus Poyet (Sunderland). Is it just a coincidence? Or are South American managers starting to become more important in the global game?

“Just as the likes of Zanetti, Crespo, Fonseca, Recoba and Zamorano opened the doors for more Argentines, Chileans and Uruguayans playing in Europe in the 90s allowed more compatriots to arrive in the future,” explains former Chile manager Claudio Borghi. “In the end, football is not so different.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But for South American bosses, Europe wasn't always a managerial paradise - in fact, it was much more hostile.

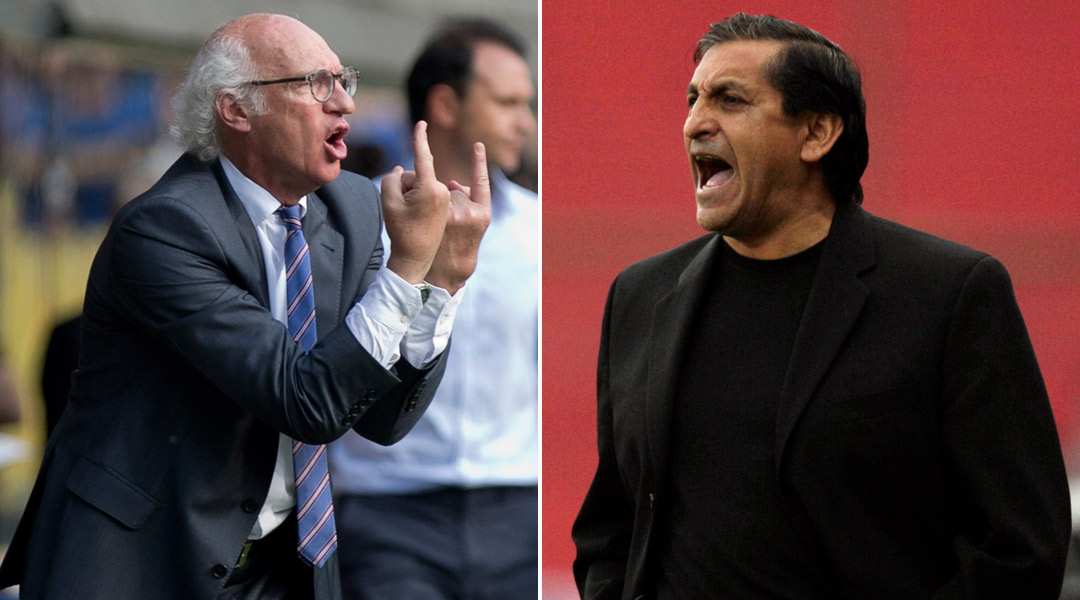

Not surprisingly, the two greatest Argentine managers of the last two decades, Carlos Bianchi and Ramon Diaz, would probably consider a war declaration if asked about their European experiences. Diaz, despite winning more titles than anyone else for River Plate (five local titles, one Copa Libertadores and a Supercopa), barely managed to coach Oxford United during a short, intriguing stint in 2004. Worse, the unbeatable Bianchi, who won four Copa Libertadores and three Intercontinental Cups with two different clubs (Vélez and Boca Juniors), oversaw consecutive failures as soon as he landed in Europe: sacked after nine months at Roma (1995) and shoved 10 years later at Atlético Madrid just six months after taking over.

Only a Soviet-minded boss like Héctor Cúper managed to stay afloat in Europe - if only for a while. He was capable of mounting serious challenges against the ever-powerful Barcelona and Real Madrid, first with Mallorca and then with Valencia. But becoming a serial earner of silver medals, plus arguments with Ronaldo and other top players at Inter, ultimately contributed to his decline: he resigned at Mallorca (1999) and Racing Santander (2011) when each side propped up the league, in between being given the boot by second-bottom Real Betis (2007) and Parma (2008), a week before the latter were relegated. Now he manages in the Emirates.

There has been no room in Europe for any Copa Libertadores-winning manager of the last 10 years. While the likes of Jose Mourinho, Carlo Ancelotti, Frank Rijkaard and Pep Guardiola were lifting the Champions League trophy, no European side (forget about a top club, just any club) fancied betting on Edgardo Bauza, Ademar Braga, Miguel Angel Russo, Muricy Ramalho or Paulo Autuori, even if they were South American champions. It was Europe for the Europeans.

Without even knowing it, Guardiola helped to change this idea. Pep’s tour in South America only came to light after he started racking up titles. Suddenly the world discovered that in order to make up his mind and become a football manager, he’d spoken for eight hours with Bielsa, had had a drink with César Menotti and was struck by the concepts of Ricardo La Volpe, the Argentine whose name became a football philosophy in Mexico, just like Menotti or Bilardo in Argentina and Spain. Pep also spoke to Julio Velasco, an Argentine volleyball coach who became famous in Italy, from whom he took the idea that players shouldn’t be treated as equals, but that they were individuals and had to be treated that way.

The good results and performances of Chile (revolutionised by Bielsa) and Paraguay (with Bielsa disciple Gerardo Martino), added a varnish of respect for the Argentine school of management. A few years ago, Martino told El Gráfico: “It’s true that they compare me with Bielsa, and I know it’s not true because he is the best, but it’s also good for me because only one is able to get Bielsa, the rest want his imitators.”

In Chile, Jorge Sampaoli gave form to one of the most attack-minded teams of the decade: Universidad de Chile. Sampaoli was a Bielsa admirer so much that he’d reproduce Bielsa’s press conferences while jogging in the park. It seemed an almost natural step to take over Chile, a country that had been struck by so-called “Bielsa widowers”. Sampaoli revitalised the national team and they sealed World Cup qualification with ease.

Manchester City’s Pellegrini is a vital link for the remaining South American managers. He had already caught the attention of the continent while managing Universidad Catolica, then Liga de Quito and finally Argentine side San Lorenzo. Néstor Gorosito, a San Lorenzo icon of the last 30 years, was the one who recommended him to the club’s board. “Nobody really knew him, but I’d had him in Catolica and he was the best manager I’ve ever worked with,” he recalls.

Argentina was just as hostile as Europe for foreign managers, but The Engineer dominated it with ease. The players he managed at San Lorenzo and River now use him as the model of the coach they’d like to become.

It’s exactly the influence that Bielsa created with the Newell’s Old Boys players he managed in the early 90s. “The old ones were worried because we knew that he was weird and would make us run like never before in our lives, but the youngsters were used to working for him in the reserves and they were more docile,” explains his former midfield anchorman, Juan José Llop.

While Bielsa had to convince Martino to run more, he treated the youngsters differently. “He’d give us homework, so we had to prepare a report of the next team we would play against. We had to read El Gráfico magazine, see the formation, check certain aspects of the game and then write it down in paper,” recalls centre-back Fernando Gamboa, who played alongside Mauricio Pochettino.

Only one player in that squad didn’t become a manager. On top of Martino and Pochettino, some are in Mexico, some in Chile (Eduardo Berizzo recently took O’Higgins to the national title), some in Argentina’s top flight and some in lower leagues - but they all belong in the dugout. A few years from now, Pellegrini’s influence will be visible just as Bielsa’s is now.

Another example is José Pekerman, who, after a stunning decade full of silverware with Argentina's U20s and a fairly good World Cup in 2006, had only managed to get his chance with Spanish second division side Leganés. But while he appeared to be on the verge of retirement, Pekerman (who inspired Oscar Tabárez’s juvenile revolution in Uruguay) was appointed as Colombia manager and moulded the most serious Colombian team since the early 90s: deadly in attack and hard-working in defence.

Languages are also vital for respect, and several South American players are now capable of speaking perfect Italian, good French or decent English. Diego Simeone, for instance, was convinced that he’d be Atlético Madrid, Lazio and Inter manager one day. But in Atlético’s case, he also knew that the opportunity would come in the worst circumstances.

“We were aware of that, and it was just like we had imagined,” recalls Simeone, who hardly uses 'I' and prefers to speak on behalf of his entire backroom staff. “We were travelling to take over a hot seat, with the team close to the relegation zone, and that’s how it all started.”

SEE ALSO Simeone has sparked Atletico revolution by moulding club in his image

But even if he pulled off a football miracle, Simeone had already managed four Argentine clubs (winning titles with two) and one Italian side (Catania, who he saved from relegation). He was young, but at the same time so experienced. That’s not by chance.

Argentina, Uruguay and Chile (with Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru following them) are betting hard on young managers. It’s getting more and more common to see recently retired players take charge (as was the case with Simeone at Racing), and old managers aren't getting as many offers as they would have a few years ago. “Football has changed. The age gap is important, even if it's more important to understand what’s going on with the players nowadays,” tells an insider from a big club.

The superstitious managers so common in the 90s are now something of a laughing stock for the current generation of players. It’s one of the reasons why Argentina haven't done well in the last eight years: Alfio Basile, who believed more in superstitions than tactical work, could never win the squad's support; Diego Maradona, with his “let’s eat their hearts”-type exclamations, soon made the players realise they weren't going to get the precise guidelines they were used to at their top European clubs.

Now South American managers are better prepared, open to new exercises and more modern approaches. And European clubs are trusting them. In many cases, it’s vital that they left a good impression as players.

“I don’t think it’s entirely due to a revolution or anything like that,” says Guillermo Barros Schelotto, who has recently won the Copa Sudamericana with minnows Lanus, and looks the next prospect for European management. More likely it's because certain ideas are more likely to succeed in certain football clubs, which is why they bet on these managers regardless of nationality.”

Knowing that the two last Argentine champions, Newell’s and San Lorenzo, lost their managers right after winning the title (Martino to Barcelona and Pizzi to Valencia), Guillermo says glory wouldn’t change his plans. “I don’t think whoever wins gets an automatic chance of managing in Europe, it all depends on how you’ve won,” he says. “Martino’s case, for instance, happened because they were aware of his progress here with Newell’s, and not just the results.”

But it’s also important to notice that not even the pressures of managing Barcelona or Real Madrid (even playing mind games against Mourinho), can match those of South America. Pellegrini was sacked from River right after winning the title because he hadn’t used the classic 4-3-1-2 system and opted for a 4-4-2 instead. Martino had already decided to resign at Newell’s because he considered Argentine football “toxic”. Jorge Valdano always refused to be part of a game where hooligans are often part of negotiations. Nelson Vivas resigned at Quilmes after punching a fan that had been insulting him for several games. Ramon Diaz had to use an umbrella to reach the dugout of La Bombonera, and not always when it was raining.

Boca’s Carlos Bianchi recently explained one of the main differences: “Arsène Wenger has not won anything for Arsenal in the last 10 years. I was with him and he told me: ‘But nobody here says that’. Well, in Argentina, everybody reminds you all the time that you haven’t won. And only one gets the chance of winning. Another year without winning would not be tolerated.”

Simeone agrees with the idea that the atmosphere in Europe is far more positive, but also that the South Americans who arrive there have developed a shield that makes things easier as players or managers. After coaching in Argentina, Uruguay or in the Copa Libertadores, Europe is the paradise.

“I will never forget the day I decided to look at the website of an Argentine newspaper,” he recalled a few months ago, in an interview for El Gráfico. “We had already won two titles, the Europa League and European Super Cup. And we were second in La Liga. Us, with our humble side, against the world’s best, with Messi, Iniesta and the rest.

“It was close to Christmas, so perhaps I was feeling a little bit emotional and wanted a ‘caress’. So I decided to read the comments from the people, something I never do. What a mistake! You can’t imagine the things they were saying! Out of 10, eight would say terrible things, one that you couldn’t understand if it was with you or against you, and just one congratulating you for the campaign. So you ask yourself: Why are we like that?”

The March 2014 issue of FourFourTwo means our exclusive chat with Manuel Pellegrini, an exclusive sit-down with everyone's favourite Mario, origins of the terrace chant, on the ground with troubled Hyde, England's first foreign legion, David Ginola One-on-One, football's fashion disasters, trending in the Champions League, and is passion all it's cracked up to be? Available in print and in a specially-designed-for-iPad version.