How US soccer rescued Arsenal in the mid-80s – and changed English football

With Arsenal in the middle of their US pre season tour, Jon Spurling explains how ex-vice chairman David Dein's obsession with stateside soccer helped transform an ailing club

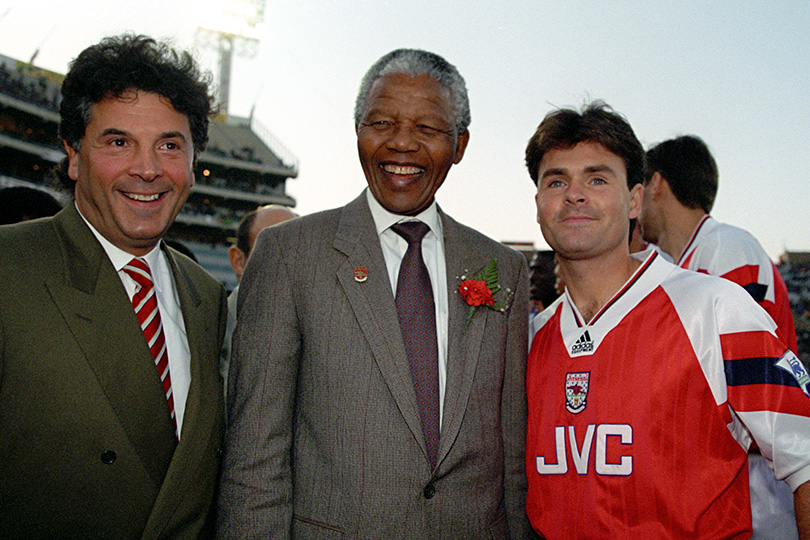

“I think that English football can learn a lot from US sports,” argued David Dein, shortly after joining the Arsenal board in 1983. “The stadia are more comfortable and family friendly. It’s all designed to enhance the spectators’ enjoyment and experience of the game.”

When the former commodities entrepreneur invested the princely sum of £293,000 in a club that was mired in mid-table, the Gunners' old Etonian chairman Peter Hill-Wood dismissed it as “dead money”.

In truth it was 'new money', and Dein was among the first in a new breed of young executives who realised that money talked in football. Within a decade, Dein’s driving ambition saw Arsenal – and to a large degree, English football – embrace many of the US sport’s facets which he so admired, making Dein seriously rich in the process. On occasion, it was more by accident than design.

Throughout the 1970s and early ‘80s, Dein often stayed at the Florida family home of his American wife Barbara. He would attend NASL games whenever possible, and was bowled over not simply by the luxurious all-seater stadia, but the razzamatazz and showbiz elements of the game.

Dein also became acutely aware of the corporate market, expansion of club brands and free market elements of American TV deals. “In the US,” he explained, “if the TV deal is poor or non-existent, the product fails.”

The NASL may have folded by the mid-80s, but Dein was convinced that by harvesting the very best of US business practice and sporting gizmos, English football – beset by hooliganism, declining attendances and crumbling terracing – could flourish once more. At Arsenal, he pushed his agenda forward with gusto, but his revolutionary ideas didn’t always meet with approval.

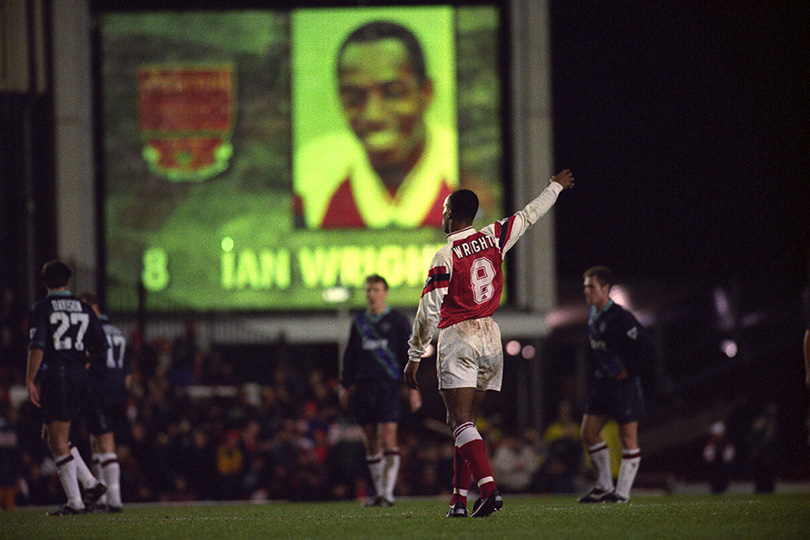

When the Gunners faced Luton at Highbury in the opening game of the 1983/84 season, the players emerged from the tunnel individually, after new stadium MC Jerome Anderson (who later became Ian Wright’s agent) barked out their names. Such grandiose entrances were part and parcel of US soccer, but Arsenal’s new £650,000 star man Charlie Nicholas (who emerged last for dramatic effect) was less than impressed. “I didn’t want that kind of hype,” he recalls. “I just wanted to be part of the Arsenal team.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

In future, the players emerged as one. Dein’s notion to erect a giant Diamond Vision video screen – which would show highlights, replays and in effect be an ‘80s version of Arsenal TV – was initially thwarted by the authorities due to noise pollution concerns in N5. Later, it proved popular with fans and was used to show Arsenal away games at Highbury.

RECOMMENDED The worst five months in English football: Thatcher, fighting and fatalities in 1985

By 1989, Dein had morphed into British football’s most prominent executive figure. As Arsenal vice chairman, he now controlled 41% of club shares and was carnivorous in his approach to gaining more. He oversaw the expansion of Arsenal’s commercial outlets, which he’d likened to a ‘Manchester bus shelter’ when he first arrived at the club. The Arsenal World of Sport at Finsbury Park station appeared, and the number of ‘Make Money With Arsenal’ girls at games increased exponentially.

In late 1987, the club announced the proposed £6.4m development of executive boxes at the Clock End, with Dein describing the scheme as “the very best in executive and catering facilities; an exciting prospect as we head towards the 21st century”. Once again, Dein referred to the fact that US sports had “long embraced this side of the game”, neglecting to mention that Tottenham and Aston Villa had long beaten Arsenal to the punch by incorporating executive boxes in the ‘70s and early ‘80s.

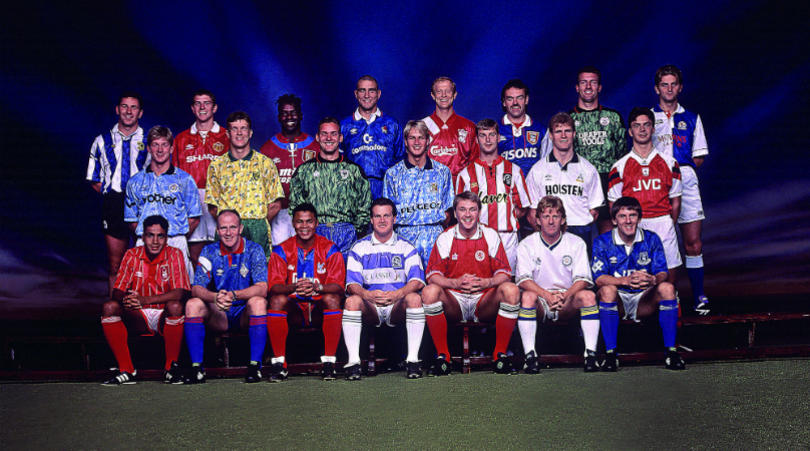

As well as redesigning Highbury, Dein was also busy heading up the new £44m TV deal with ITV, insisting that “football clubs – especially in the absence of European football, with English clubs banned – must continue to add new revenue streams in order to be competitive. His plan to cut the old First Division to 10 or 12 clubs, thus creating a ‘Super League’ (“the top flight must be more streamlined and more profitable,” he said), never came to fruition, but the Premier League – which kicked off some three-and-a-half years later – had its origins in these negotiations.

The Hillsborough disaster in 1989, and subsequent Taylor Report which deemed that top-flight stadia should be all-seater, forced clubs to embark on costly building programmes. Arsenal’s was arguably the most controversial of all. The club decided to finance the £22.5m cost of turning Highbury all-seater through a bond or debenture scheme. The club hoped to sell £16.5m worth of bonds to supporters, while the rest would come from within the club’s swelling coffers – helped by the title wins of George Graham’s sides in 1989 and 1991, and the club’s rapid commercialisation.

Several clubs in the US had redeveloped their grounds through such schemes, but fears that many Arsenal fans – who’d previously paid to stand on the North Bank or Clock End – would be priced out by a gentrified new stadium were proved entirely justified. “The club is not a charitable institution,” argued Dein, when he was challenged by members of the Independent Arsenal Supporters Association (IASA) in 1991.

As the Premier League era dawned in 1992, Dein lost the battle to ensure that ITV continued to screen live games on The Big Match Live (the contract was awarded to Rupert Murdoch’s Sky TV). But he’d inadvertently won the war.

Within a few years his shares were worth a staggering £35m, and all-seater Highbury – despite being largely hemmed in by the surrounding streets – adhered largely to the US model which Dein had advocated.

“If I have to sit at football matches,” one Arsenal fan told Dein at half-time against Coventry in August 1993, “then this stand is the dog’s bollocks.”

But it cost a pretty penny to sit in, and Arsenal’s increasingly well-heeled audience, clad in their replica kits, armed with bags of merchandise and munching on the nachos which were available in numerous commercial outlets, became the subject of derision on TV comedies like the Fast Show. Giant Sony Jumbotron screens occupied pride of place in diagonally opposite corners of the ground, the Clock End corporate boxes were full, and Arsenal’s global brand continued to prosper as star players from abroad poured in. Other clubs modelled their approaches on the Gunners’.

The entrepreneurial Dein – who quickly became de facto chairman – was an often-divisive character at Highbury. Thanks largely to the ideas gleaned from his trips across the Atlantic, however, he’d transformed Arsenal into a title-winning force, and dragged English football kicking and screaming into a brasher new era.

THEN TRY... Wenger at Nagoya Grampus Eight: how Arsene rediscovered his greatest love in Japan

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get 5 issues of the world's greatest football magazine for £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a pint in London. Cheers!

NOW READ

OPINION Arsenal's captain curse: how Laurent Koscielny exacerbates an already-embarrassing problem

NOSTALGIA Why does Championship Manager 00/01 still hold such a special place in the hearts of so many people?

Jon Spurling is a history and politics teacher in his day job, but has written articles and interviewed footballers for numerous publications at home and abroad over the last 25 years. He is a long-time contributor to FourFourTwo and has authored seven books, including the best-selling Highbury: The Story of Arsenal in N5, and Get It On: How The '70s Rocked Football was published in March 2022.