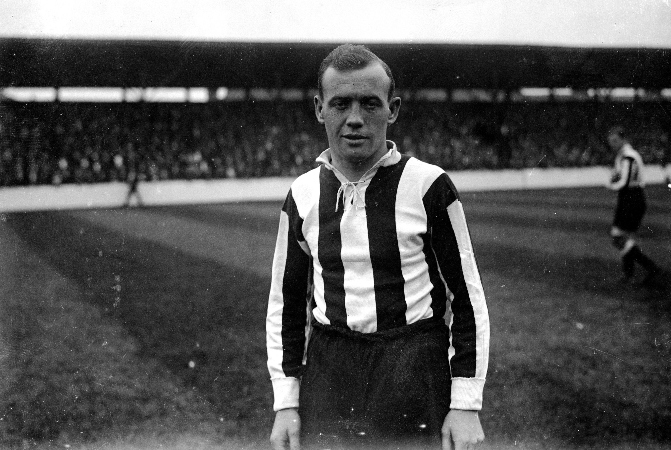

Hughie Gallacher: the free-scoring Newcastle and Chelsea forward who became football’s original bad boy

He may not be a household name now – but in the 1920s, the goal-getting, wise-cracking, big-drinking Gallacher was British football’s first icon... before meeting a tragic end

Cigarette dangling from his lips, bowler-hatted, both shoulders sloped beneath a double-breasted coat, hands clasped across his waist, Hughie Gallacher stares cold-eyed down the camera lens.

Flanked by Jack Crawford and Andy Wilson, the Chelsea strike trio look the last word in 1930s mobster chic. But it’s Gallacher to whom your gaze is first drawn. Unlike his Blues team-mates, his demeanour seems unforced. It’s as if he actually is public enemy No.1.

The staged shot, snapped in the winter of 1931, wasn’t so far from the truth. Across a 20-year career yielding an eye-popping 463 goals in 624 matches, Gallacher’s name gave centre-halves and officials palpitations and set terrace pulses racing.

His off-field antics created enough column inches to dwarf his 5ft 5in frame, whether they were real, exaggerated, or plain imagined. Constantly railing against authority and the punishment meted out to him on the pitch, Hughie was rarely out of the public eye. But, for all his rough edges, he was universally respected and admired by peers who loved his brilliance and bravery.

More than 90 summers have passed since Gallacher, leading the line and the team, helped Newcastle United to their last top-flight title in 1926-27. He scored 36 league goals – still a club record – and set up countless chances for others in a world where assists were yet to be measured and Pathé News clips were as good as screen coverage got.

A year later in March 1928, Gallacher, collar upturned, limbs a jinking whirr, proved the protagonist of Scotland’s pint-sized, punch-packing ‘Wembley Wizards’, who thrashed England 5-1 with a dazzling display of ball craft. “Never was a country more humiliated on its own soil,” ran the hand-wringing report in the Sunday Chronicle.

The Newcastle jersey has scarcely altered since Gallacher’s day. It remains the same black and white, though the game has long been played in Technicolor. At St James’ Park, as fans unfurl a flag bearing his face at the Gallowgate End, they still remember Hughie. As they do at his other ports of call, from spells with Queen of the South and Gateshead which bookended his goal-filled career, via Airdrieonians, Chelsea, Derby County, Notts County and Grimsby Town.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

When Alan Shearer, who’d missed his own induction to the English Football Hall of Fame in 2004, made it along in 2014, he did so on the night Gallacher joined the pantheon. As he presented Gallacher’s son Matthew with a commemorative trophy, Shearer recalled something his own dad said to him:

“No matter how many goals you score, son, you’ll never be as good as Gallacher.” Shearer Sr had a point. His son’s 206 Newcastle goals in 404 outings came at 0.51 a game. Gallacher’s 143 in 174 appearances came at 0.82. And he didn’t take penalties…

His was arguably the first football life lived under the microscope – a fascinating flash into a future where footballers became cult heroes, the minutiae of their existence dissected by those who barely knew them, but imagined they did.

A proto George Best, blessed like his fellow Celt with unearthly skills, Gallacher never reached his three-score years either. One mid-June day in 1957, aged just 54, ‘Wee Hughie’ was dead by his own hand. Drama dogged him to the last, tragic whistle of his life: an oncoming train sweeping round the Tyne near his Gateshead home.

Humble beginnings in a tiny Scottish town

There weren’t many obvious routes out of Bellshill, North Lanarkshire when Hugh Kilpatrick Gallacher entered the world on February 2, 1903; a second child to Matthew and his wife Margaret. Life in this collection of villages 10 miles to Glasgow’s south-east orbited around the pit and outsiders called it ‘Cannibal Island’, such was the toughness forced on anyone who grew up there.

Coal was king where scraping a living was concerned, but for those who preferred a working life above ground, Bellshill’s rich seam of football offered dreamers a way out.

Jimmy McMullan, who skippered the ‘Wembley Wizards’, was a local, as was one of Gallacher’s closest friends, Alex James, 18 months his senior. James, the baggy-shorted playmaker who led Arsenal to four league titles, and Hughie honed their smarts biffing a two-penny ball – or ‘tanna ba’– in the shadow of the slag heaps. If they couldn’t afford a ball, which was often, they’d just kick whatever was to hand.

Matt Busby, Gallacher’s second cousin and yet another product of Bellshill’s fertile breeding ground, recalled how instructive watching these rough diamonds had proved.

“They’d have been about 18 or 19, and I [would have been] about nine or 10,” he explained. “They were little whippets as footballers go, but they were famous. Everybody in Bellshill knew what players they were. As insignificant though Bellshill might seem in the big world of football, I saw magic in those days – the magic of two of the greatest footballers in the game’s history in one small village.”

That magic soon attracted a much wider audience. The youngster’s skills – abetted by his low centre of gravity – were allied to impressive strength from the grind of working at Mossend’s munitions factories during the War years and, subsequently, Hattonrigg Colliery.

A love of boxing – Hughie’s school sparring partners Johnny Brown and Tommy Milligan became British bantamweight and welterweight champions respectively – helped to compensate for his lack of inches.

Gallacher turned 17 in 1920, an eventful year. That July he married Annie McIlvaney, a Catholic from Hattonrigg, which incensed his Irish Protestant father – and the pair had a child, Hughie Jr, who tragically died before his first birthday.

Gallacher’s showings at junior level for Tannochside Athletic opened the door at Bellshill Athletic when they were a man short. Bellshill had rejected Gallacher and James on height grounds two years earlier – but a debut goal made them sit up.

Genuinely two-footed, he packed a mule-like kick in either, and his ability to squeeze past or hold off opponents was allied to intuitive positional play and a precise touch. He was nails, too, once leaving the field three times for treatment only to return – and score each time.

By December, Gallacher was selected for the Scottish Juniors, equalising in a 1-1 draw against Ireland.

Queen of the South made their move at the turn of 1921, offering £5 a week and a £30 signing-on fee. “To be paid for playing soccer – I just couldn’t believe it,” he chuckled. Scoring goals at this level was like shelling peas: 19 in nine appearances included four on his debut against St Cuthbert Wanderers.

However, just as the scouts started to converge, Gallacher was rushed to hospital with double pneumonia.

Briefly on the critical list, five weeks out of action was good news for Airdrie boss John Chapman, who trumped would-be suitors St Mirren by visiting him and capturing his signature in May 1921, bizarrely in an undertaker’s office belonging to a club director.

Airdrie, Scottish top flight also-rans, had achieved little to speak of in their 43-year history. Gallacher soon changed that, inspiring them to challenge the Auld Firm hegemony.

His 100 goals in 129 league and cup games helped the Diamonds to four consecutive 2nd-placed finishes from 1923 onwards. Silverware did eventually arrive in the shape of their first, and only, Scottish Cup in 1924. Gallacher – who else? – followed his Scotland debut against Northern Ireland a month earlier with a standout showing in the 2-0 victory over Hibernian at Ibrox.

"I learned swear words from Hughie I had never heard before"

Success had made him a marked man, on and off the pitch. After netting five for the Scottish League in a 7-3 romp over the Irish League in November 1925, Gallacher narrowly dodged a sniper’s bullet. He’d received a note at half-time of the Belfast meeting supposedly from Irish extremists, suggesting he let up after scoring three goals in 14 minutes, but ignored it.

A few days on, still in Ireland visiting friends, a bullet hit a wall yards from him. “It seems I still haven’t managed to teach the Irish how to shoot straight,” he quipped. He later revealed just how rattled he’d been. “If ever a world record was set for the 100 yards, I did it then,” he said.

Heavy challenges and his sharp-tongued response – the product of a background where a backward step was perceived as a weakness – often landed him in trouble. A five-match ban headlined the Scottish FA’s increasingly lengthy Gallacher rap sheet, and Airdrie team-mate Bob McPhail admitted: “He was a selfish wee fellow and he thought of no one but himself. He had a vicious tongue and used it on opponents. I learned swear words from Hughie I had never heard before.”

But his will to win and dedication to training were admired by many, not to mention ball-playing talents that led one observer to comment that Gallacher seemed to “possess more than the usual complement of feet.” McPhail said that his colleague “had a superb sense of getting himself into the right position, and he was never caught off balance.”

By the winter of 1925, the game was afoot to secure his services south of the border, and Newcastle United finally got their man at the fourth attempt. Signed in December for a transfer fee many believed to be a British record at the time, 22-year-old Gallacher was joining a club that had finished 6th, 10 points behind the champions, Huddersfield Town, in 1924-25.

He made his debut against Everton four days later, and while Dixie Dean hit a hat-trick for the hosts, Hughie’s brace in a 3-3 draw stood out. Dean still vividly recalled the encounter more than 40 years later. “The finest centre-forward I’ve ever seen,” he said. “He had brilliant ball control, the heart of a lion – he needed it with the stick he had to take – and complete and utter confidence in his ability.”

That first half-season at St James’ Park brought 23 goals in just 19 league outings. The game was now entering a new era with a change to the offside law – largely in response to Newcastle’s Bill McCracken perfecting the art of stepping up to catch out errant strikers.

Now two, rather than three, defenders needed to be between attacker and goal. A forward of Gallacher’s nous could fill his boots, and fill them he did. The Magpies had memorable strikers in the past, but no one like this.

Gallacher began his 1926-27 goal rush with all four in United’s rout of Aston Villa. His celebrity status was burgeoning. Journalist Duncan Hamilton, author of The Footballer Who Could Fly, inspired by his dad’s devotion to Newcastle, was smitten himself after hearing his father’s memories of the marksman. “Off the field, always snazzily attired, he looked like a prosperous businessman about to close a deal,” writes Hamilton.

“White spats, bowler hat, silk tie and button-down collar, a handkerchief water-falling from the breast pocket of his jacket and a flower pinned to his lapel. On the field he looked like a street fighter: fists clenched, eyes as hard as flints, shoulders aggressively hunched and legs scarred and pitted by defenders’ studs.”

The cult of the No.9 was now established. But as Gallacher powered Newcastle’s diminutive forward line to the club’s fourth title – none of the front five were taller than 5ft 7in – with it came problems, not least the flesh gouged from his legs so often that team-mates said it hung off in scraps. Gallacher ended up wearing half an inch of cotton wool under his shin pads as protection.

Regularly goaded on the pitch, he struggled to keep his temper. “I’m pretty tough,” he said. “But not tough enough to knit wire netting or bend crowbars – or take deliberate rough usage with a smile.”

Free-for-alls were commonplace, including one at Tottenham which caused the referee to halt proceedings and lecture both teams. Gallacher seemed to thrive on the tension. Missing only four league matches all season, his double in the penultimate fixture – a 2-1 win at home to Sheffield Wednesday – confirmed the Tynesiders as champions. Off the pitch, his blossoming romance with Hannah Anderson (right) – the teenage daughter of a local publican who later became his wife – added fuel to the fire.

Gallacher, though long-estranged, was still officially married to Annie, with divorce rare at the time. When her brother heard about the relationship, the pair’s public set-to ended in court.

Tales of his drinking bouts, pre- or post-match, set tongues wagging, too. Even if these contained some element of truth, they were usually exaggerated, as noted by Paul Joannou, Newcastle’s official historian and author of The Hughie Gallacher Story.

“He liked a drink, but wasn’t the first footballer who had that trait,” he explains. “He was his own man, I suppose, and didn’t like being told what he could – or couldn’t – do in an era when clubs and the football authorities had an almost slave-like rule on footballers. So he rebelled. In the context of society as it is now, we’d perhaps say he had a point in most of the rows with clubs and directors.”

Trouble in the Toon

On New Year’s Eve 1927, still incensed with referee Bert Fogg after his refusal to award a penalty in a 3-2 home defeat to Huddersfield, Gallacher followed Fogg into his dressing room. Initially intending to apologise, when he saw the official leaning over a half-filled bath, he pushed him in. He was suspended for two months.

Although he continued to find the net, Newcastle failed to sustain those heady heights. An ill-tempered close-season tour of Europe in 1929 ended in Budapest after the team – Gallacher first and foremost – were accused of drunkenness in a game against a Hungarian XI in which he was sent off for scrapping.

The players claimed they’d rinsed their mouths out with Scotch and water due to the heat, and the FA – for once – bought their story, but the last-chance saloon doors were inching shut on Tyneside.

Having pushed for a move shortly after that European jaunt, Hughie lasted one more campaign, in which his 34 goals kept Newcastle up. It was the fifth consecutive season he’d topped United’s scoring chart. Gallacher also found himself at the centre of the first ‘club vs country’ row, playing for Newcastle in April’s 1-1 draw with Arsenal instead of Scotland, who lost 5-2 to England at Wembley.

His love affair with the Magpies was finally over when, despite having seemingly penned a new deal for 1930-31, he learned of talks to sell him to newly promoted Chelsea. The deal was publicised at £10,000 – though the exact sum wasn’t revealed – and fate dealt a swift hand, as he was back on Tyneside for the campaign’s second game.

It was a return that made the scenes greeting Alan Shearer’s ‘homecoming’ in 1996 look tame, with a record 68,386 crowd clambering to whatever vantage point they could to pay their respects. It was, Gallacher later revealed, the most memorable moment of his life.

Gallacher’s new side were defeated 1-0 that day, but the goals soon followed him to London. So, inevitably, did trouble, notably a fist-fight with Fulham fans after a night out that ended in his arrest for disorder. He still led the line admirably, but time was catching up with him and indiscretions such as this, combined with rumours of illegal payments, his never-ending divorce proceedings and regular quibbles over wages, eventually wore Chelsea’s patience thin.

With debts of £787 – a king’s ransom then – Gallacher, at least now able to marry, signed for Derby County in November 1934 after four seasons in the capital, with £200 paid directly to keep the bankruptcy court quiet. “I don’t like London – I can’t get used to the climate,” he joked.

Rejuvenated in fresh surroundings, he scored 38 goals in 51 league games for the Rams, who mounted a title challenge in 1935-36. They came 2nd to a Sunderland team skippered by England inside forward Raich Carter, who lifted the FA Cup a year later.

Spells with Notts County – where his attitude as captain impressed – and Grimsby – who he kept in the top flight – preceded an emotional return to the north-east with Third Division North Gateshead in 1938. The arrival of the fabled Gallacher, now 35, swelled crowds to 20,000.

Even to the last – the outbreak of the Second World War calling time on his career – he netted 18 from 31 outings. During the War years he played in – or, ironically, refereed – many charity matches. “Lay on the transport, find some size-six boots and leave the rest to me,” he said.

Given his explosive career, few would have begrudged him peace in his post-football years, though a life such as Gallacher’s was unlikely to wind down incident-free. No one could have foreseen the tragic end. Wife Hannah’s death, from a heart complaint on New Year’s Eve 1950, proved a blow greater than any in his playing days and, if he’d ever had a real problem with drink, it was now.

A tragic end to an eventful life

On a May afternoon in 1957, after an argument with son Matthew, Gallacher threw an ashtray across the room in anger, which glanced off the boy’s head. The police and NSPCC were alerted, and Hughie’s world was closing in. He became convinced authority would make the ultimate example of him, accused as he was of assault and neglect.

On June 11, the day before he was due to appear in court, Gallacher left his Gateshead home one last time. Having met friends, who later recalled his edgy demeanour, he headed for Low Fell train station and walked into the path of a train – his body was found 100 yards away.

His death was instant, but his life – part fairy tale and part cautionary tale; sinner, yet oft-sinned against – endures. Outrageous, untameably brilliant, to Newcastle supporters raised on comparatively thin gruel, he’s a reminder of why we fall in love with football. “The ordinary rules just didn’t apply to him,” Magpies team-mate Stan Seymour observed. “Stanley Matthews had only a fraction of Gallacher’s casual genius.”

Were his equivalent in existence today, it’s even less likely that Rafa Benitez could afford him. “I always think this of him,” reflects Duncan Hamilton. “If someone wrote his story as a roaring historical novel, no one would believe it.”

Agog on the Tyne? That might just do it.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get 5 issues of the world's greatest football magazine for £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a pint in London. Cheers!

NOW READ...

10 players who contradicted themselves with their transfer moves

Quiz! Can you name the top three all-time goalscorers for every current Premier League club?