'I fell in love with football as I was later to fall in love with women: Suddenly. Inexplicably. Uncritically. Giving no thought to the pain or disruption it would bring with it': Nick Hornby, Fever Pitch

Nothing speaks to fandom like Hornby's 1992 classic, published when Highbury was crumbling and football literature amounted to little more than your matchday programme. Thirty years later, FFT grabs lunch with the author himself to chew the pasta over Arsenal, Fever Pitch's legacy, the wider game - and just a touch more Arsenal...

"I sometimes wonder if [Jurassic Park author] Michael Crichton got fed up talking about dinosaurs," muses Nick Homby as we wait for a menu to appear at Demartino, the busy Italian restaurant in Fitzrovia where FFT has arranged to meet. "He had a really good idea for a book, then wrote it and ended up talking about it for the next 15 years."

There's a pregnant pause while he takes a sip of water. The audible gulp is not his.

"The thing I had to talk about and keep talking about is the centre of my life in so many ways, what with the kids and the friendships that get shaped around football, so I'm very happy to keep talking about it. I tend to have like talking about the football certainly a relief.

"The thing I had to talk about and keep talking about is the centre of my life in so many ways, what with the kids and the friendships that get shaped around football, so I'm very happy to keep talking about it. I tend to have friends who read, like movies, like music and also support Arsenal. Over the years, you can collect enough people like that to sustain your whole social life. I quite like talking about the football of the past too." Well, that's certainly a relief.

We're here because Fever Pitch, his autobiographical memoir, is 30 years old this summer and was a landmark book in so many ways. It was published three weeks after the Premier League came into being in 1992; turned into a film from his own adaptation starring Colin Firth five years later (and once again, more loosely, as an American rom-com by the Farrelly brothers in 2005); sold over a million copies worldwide; and is widely recognised as one of the most important books written about football (or indeed sport) and its place in the life of a fan. "It's something that it's stayed in print", Hornby will subsequently note modestly.

Fever Pitch made his name, of course - among a multitude of other things, he has gone on to pen novels including High Fidelity and About A Boy (both also films), and had an Oscar nomination for his screenplay of An Education-but, more than that, it helped to rescue the reputation of the reviled and traduced football fan of tabloid lore. Not that he gets much credit for it- quite the reverse in some quarters. We'll get to that presently. The first edition of Fever Pitch was subtitled 'A Fan's Life'. There's a reason for that...

How was the 2021-22 season for you?

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

"I was at the last game at home to Everton [Arsenal won 5-1 but failed to qualify for the Champions League]. That was fun, but there was a sense that everything was happening somewhere else. Tottenham were soon two-nil up and Norwich are beyond hopeless, so nobody had any expectations really. One of my boys was there, he goes home and away, and he wrote an emotional and measured piece for one of the websites. A lot of people stayed for the lap of honour and I think he felt like most of the supporters there- that there's a sense of connection with the team that hasn't been there for quite a long time."

When Fever Pitch came out, all fans could relate to the angst, though there was this nagging feeling that Gooners didn't have it quite as bad as those from other clubs...

"Well, you don't have a choice [over who you support], do you? When you get older, a big victory in something lasts you a couple of years. It's like, 'It was only yesterday, what's everyone complaining about? Oh, it wasn't yesterday, it was four years ago. My kids felt they'd been asked to support the worst team ever, because when they started going to the Emirates they were asking if they'd ever see them win anything?

"The first time I went to Wembley with the family was when we lost 2-1 to Birmingham in the [2011] League Cup Final, and that was their big chance. They were in a very bad way after the game. The next time we went was against Hull [in the 2014 FA Cup Final]. We won 3-2, but were two down in the first eight minutes. It was one of those matches when I was so angry about what happened at the start that it didn't matter what happened afterwards. I'm still furious now."

How was leaving Highbury In 2006?

"Obviously, you know it's coming. The funny thing about the last game played there was that it was the Champions League final in Paris the following week. Everyone was like, 'Goodbye Highbury... we're playing Barcelona In less than a month'. I know that's what I was thinking: European final, new stadium, nothing can stop us now. Of course, we still haven't had a serious title tilt at the Emirates yet. Everything's better than Highbury but nothing's as good. I wasn't at Anfield in '89 [for Arsenal's title win, the season leading up to it providing the backdrop to Fever Pitch], but as I wrote in the book, I haven't really regretted that because the streets around Highbury were incredible that night."

You've said that people have accused you of being single-handedly responsible for gentrifying the game..

"Well, there's a terrible amount of inverted snobbery in football. I think the idea that somebody had the temerity to write a book, and it wasn't a stupid book... that in itself was kind of middle class. After the 1990 World Cup it seemed like people [who liked football] were coming out of the woodwork, but the way I looked at it was that none of these people had ever been given a chance to say anything about football before.

"If someone famous mentioned a football team in an interview, you'd kind of notice that, but I think our society changed in the '60s with George Best, actually, and it became a much more inclusive game. I'm the product of that. The grammar-school boy who fell in love with football.

"Traditionally, I suppose I should have been more interested in rugby or cricket, but [music writer] Tony Parsons said to me once, 'Who do they think has been sitting in those stands for the past 70 years?' But yes, being held single-handedly responsible... What I noticed when High Fidelity came out, and I'd started to spend more time in the States for book tours and things, was that everybody had the same complaint about sport- it was all executive boxes and the prawn sandwich brigade. I'm responsible for that.

"I mean, a combination of Hillsborough and [Rupert] Murdoch is bigger than me. It's the wrong way of looking at it - the state of the game in the '80s had driven everybody away, and the fact people eventually came back is kind of a good thing rather than a bad thing. For the first game of the 1985/86 season at Highbury, there were 25,000 people in a ground that held 55,000. There were crumbling lumps of concrete and a terrible team in the same year as the Bradford stadium fire and the Luton-Millwall pitch battle at Kenilworth Road."

Another seminal football book, All Played Out by Pete Davies, came out just before Fever Pitch. Did you read that at the time?

"Yes. That was very useful for me, because the book helped me to get published. I spoke to Pete Davies when mine came out and, I say it helped, but I can remember being turned down by his publisher who said they didn't believe lightning would strike twice. [Laughs] [FFT: How many rejection slips did you receive?] Two or three, then I had two publishers interested, Penguin and Gollancz."

Fever Pitch came out in September 1992. How long before things started happening?

"Well, I was taken aback by how much it was reviewed and how good they were. I wasn't expecting that, but nor did it occur to me that they might be bad. I thought, 'It's my first book and they're writing this stuff, and they're only doing that because they like it, otherwise they wouldn't bother. It all went a bit quiet, then I won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year which made an immediate difference to sales.

"I remember going into Waterstone's at Camden a couple of weeks before Christmas to see if they had any copies. That was a really great moment. I looked at the new books and it wasn't there. I thought it was perhaps in the sport section upstairs, but it wasn't. A bloke walked over and said, 'Are you Nick? Will you sign some books?' I said, 'Yes, but I don't think you've got any here.' He pointed to where they were piled on the floor, where I hadn't expected to see them. It was next to Sex by Madonna and he said, 'These are our Christmas books.' [Laughs] That was pretty fun. It was No.2 every week for six months, with Wild Swans by Jung Chang at No.1. I could never quite catch up."

How do you reflect on the managers that took over after the book was published?

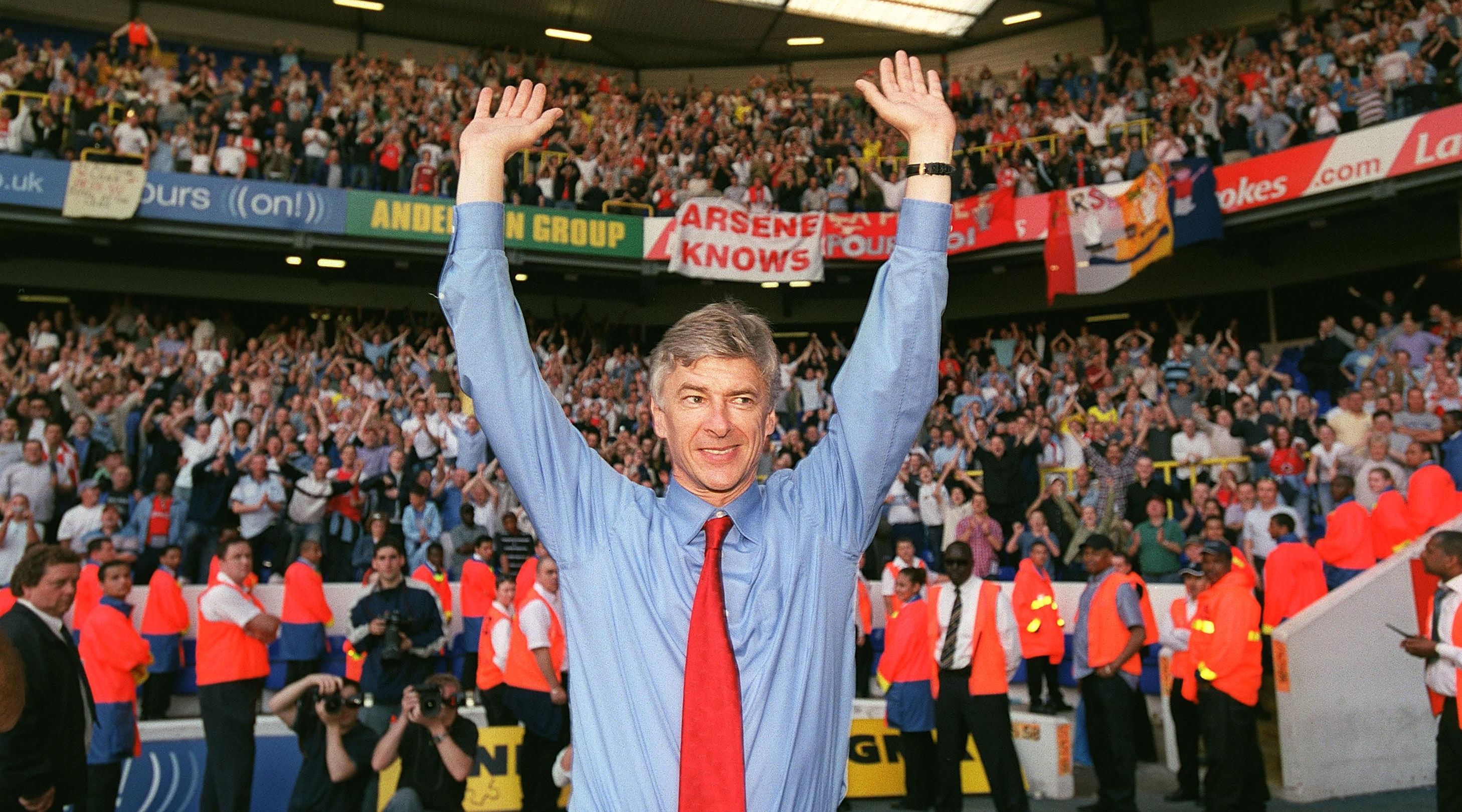

"Bruce Rioch was only there for one year, but Arsene Wenger is the greatest manager in Arsenal history. By some distance, too. It's a difficult one, because my book changed my relationship with the club - I met Arsene more than once and talked to him a couple of times quite properly."

Had he read Fever Pitch?

"Yes. My son was working in the ticket office at Crystal Palace during a gap year last summer [2021], and Patrick [Vieira] happened to notice the big Arsenal tattoo on his arm. They started chatting and when he said who his dad was, Patrick told him all the Arsenal players were given the book in translation when they first signed - I never knew that. I really admired Wenger. I was fascinated by him. He was so smart and knew so much about the world, even though he only thought about football -you couldn't get him off the subject.

"I once sat next to him at a dinner and thought, 'This must be his worst nightmare, sitting next to a supporter', so I was going to try not to ask the things I wanted to ask. It was in May, so I said, 'Have you made any nice plans for the summer?' He replied, 'No, because too many people will try to steal our best players.' That was it. That was my question to Arsene. Then he just talked solidly and brilliantly - so many incredible, interesting stories."

How did your relationship with the club change?

"Do you mean in terms of being closer to the heart of things, behind the curtain where every fan wants to be? In some ways, I suppose. I remember talking to Arsene the night before the last game of the Invincibles season [2003/04]. I went to the training ground, and I was waiting in his office there when this French guy walked in - I don't know who he was but he was really cross and thumped the desk. I asked him if he was alright, and he muttered something like, 'We cannot sign a player because of stupid English regulations.' I said, 'Anyone interesting?' And he said 'Kolo's brother' [Yaya Toure]. I suppose that's why he was off in Ukraine.

"Arsene dined out on that a lot, who he could have signed if only this or that had or hadn't happened. He goes on about [Cristiano] Ronaldo. He always said he had a story to tell when his book came out, but I went to a Q&A recently and someone asked him that story. Manchester United offered more money, so not much of a story then. Ridiculous, accusing another Premier League team of buying a player for more money. We spent big on s**t. Lots of £10 million players who weren't any good, like Tottenham with the [Gareth] Bale money."

How were you at the end of Wenger's era?

"The last two, three years, the sensible people - who I number myself one of - thought, 'At least let's fail in a different way'. I know the grass isn't greener, but it's sort of the same unproficiency sewn in, year after year. He was never interested in defenders or goalkeepers, he only ever wanted inside-forwards. When it worked, it was incredible to watch. That Van Persie-Fabregas team, and the way he coped with the new stadium thing, and getting in the top four every year, was an extraordinary achievement. But in the end you think, 'Well, if we go to Anfield or Stamford Bridge, we're going to lose six or seven-nil and I don't want to watch it...' He was obsessed with football."

You wrote the adaptation for the first film version of your book. Was that important?

"Yes, very. I wanted it to be faithful to my book because it was my story and involves all my family - I wanted to make sure that nobody took liberties with it. At the same time, I knew it was going to be a different thing from the book, so the key was that Colin Firth needed to come across as a genuine fan with all the hopeless, disastrous commitment to a team or cause that we all have. I think we did that. I never thought the movie would get made - I kept writing and re-writing the screenplays, but we eventually started filming at Highbury after the Bolton game on the final day of the 1995/96 season. By the time it had come out, Arsene was in charge. I exec-produced the second film but that was an entirely different beast if we're talking football."

As Fever Pitch Illustrates, there's a cycle of life and a fan's football club is right at the centre of that. Now you're watching your kids begin to appreciate the same thing...

"I was telling them earlier this year that this young Arsenal team is a bit like 1986 for us. It was George [Graham]'s first season: it was Rocastle, Thomas, Adams, all in the team at the same time, and we thought this could be really good in a couple of years. And it was... It's funny watching them going through the same thought processes now.

"They went to primary school right on Highbury Corner - I used to go and pick them up sometimes and said to them once, 'You've got to watch this kid playing, he's amazing.' No one could take the ball off him, he was so quick. And there was another one, two of them in the same game. On the way back, they said, 'Do you think he'll play for Arsenal, Dad?' And I did the explanation as I do in the chapter about Gus Caesar in the book - probably the one I enjoyed writing the most - about how he might be the best at primary school, but then he has to be the best at every level after that and just how good you have to be to make it as a professional player.

"Around three or four years later, I walked in and the England youth team were on TV holding up the World Cup. My son said, 'It's those two kids we were watching who you said would never make it.' They were in the squad. That was a funny moment. Luckily, they're also Tottenham players so aren't going to make it to the very top."

What did your dad make of the book? We only ask because the dedication at the front - 'For my mother, and my father' - is very pointed.

"The comma speaks volumes. I was so careful about my dad in that book because he behaved like a complete c**t in my childhood, and I really tiptoed around it in a way that wouldn't offend him. But the first thing he said was, 'It's not like there's any warmth there.' I thought, 'That's funny, you lived in a different country most of my childhood'. Then more and more people kept coming up to him and saying, 'Did your son write Fever Pitch?' For the rest of his life, he had a poster of the book on his kitchen wall. He was proud of it in the end."

This interview first appeared in the August 2022 edition of FourFourTwo magazine