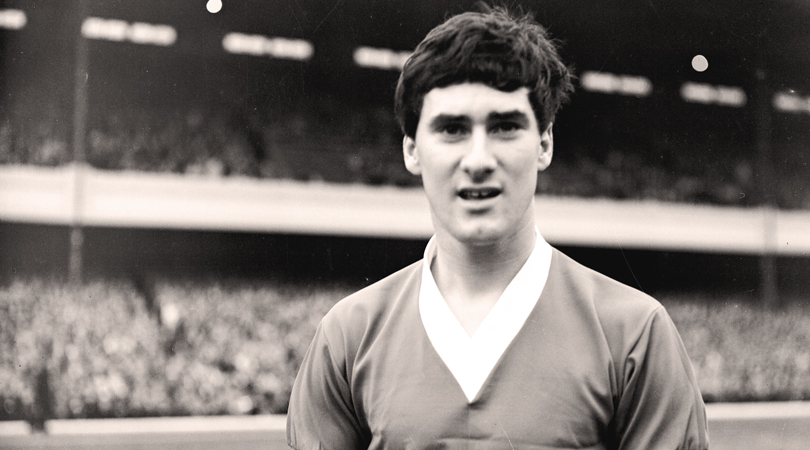

Jim Baxter: remembering an immortal of Scottish football

'Slim' Jim Baxter died 19 years ago today, but the Scottish icon's legacy as a player has only grown in the years since he graced a pitch

Rangers dominated the 1963 Scottish Cup Final, but it finished 1-1 and needed a replay.

The night before the second game, Jim Baxter didn’t sleep. He would eventually find his bed at 9am, but not before another dance with the Glasgow nightlife. ‘Slim’ Jim claimed to have won £3,000 at the roulette table. Even conservative estimates pitched his winnings at £1,800. Whatever the exact truth, by the time he was sitting down for breakfast at his parents’ house, he had earned almost as much in a night as he would from a year’s salary.

That afternoon, after a few hours’ sleep, he and his left foot would captivate 120,000 fans at Hampden Park, giving what was by his own reckoning his finest performance against Celtic in a 3-0 win.

It’s one of the anecdotes which sustains Baxter’s legend. Today, 19 years after his death, he remains a beguiling figure. Not just a pastiche of other greats who have been consumed by their compulsions and vices, but a real and original immortal of Scottish football.

Baxter was from Hill of Beath, a small village in Fife which was built to the serve the mining community. Former Scotland captain Willie Cunningham was born there, too and Celtic’s Scott Brown also attended the village’s primary school. In a 1995 interview, he likened his upbringing to a scene from a Charles Dickens novel and recalled the forty-a-side playground matches which would have first demanded his delicate touch and technique.

His first steps into adult football came with Raith Rovers. He initially remained part-time, though. He was earning £7 a week sorting the stone from the coal at Fordel Colliary and £3 a week in Raith’s reserves. That would become a guaranteed £9 a week when he made Bert Herdman’s first team and, with his pit days behind him, Baxter’s professional career was underway.

It had cost Raith just £200 to sign Baxter and they would sell him to Rangers for £17,500. According to legend, Scot Symon – manager at Ibrox between 1954 and 1967 – became determined to sign the left-half after watching him orchestrate a win over his side in late 1959.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

According to Ken Gallacher’s fine biography of Baxter, Symon would admit as much when a deal was completed in 1960, telling him that:

“You controlled everything and that was in a Raith Rovers jersey and I wondered just what you would be capable of in a Rangers jersey.”

The answer was three Scottish league titles, three Scottish Cups, and four Scottish league cups. Had it not been for a Fiorentina side managed by Nandor Hidegkuti - England’s tormentor from 1953 - Rangers and Baxter might also have won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1961. Were it not for a broken leg in Vienna, he and they might have won the European Cup in 1965. Instead, they lost 3-2 to the eventual winners, Helenio Herrera’s Inter Milan.

But reducing him to his medals misses the point. Baxter was entertainment and flair. He was mischief. The greatest compliment he’s due today is the observation that his style hasn’t aged. In most cases, footballers are prisoners of their own era. That’s particularly true prior to the 1970s, before which the heavy balls, thick boots and boggy pitches often conspired to reduce players, obscuring their true technical merits.

Not Baxter, though. Not with those touches, those turns and all that elegance. He could tease with the ball, twisting defenders into a knot. Or he could rake it forty yards, dropping it on any blade of grass. Almost all of the first-hand accounts describe a uniquely flippant person, completely unaffected by the game’s pressure, and that seems evident in the way he played. A football match has its own rhythm. Baxter, like all great players do, played at his own.

Never more so than against England. Baxter won 34 caps for Scotland, but three of them stand above the rest.

The first was the win over England in 1962, in a 2-0 revenge for the 9-3 humbling suffered the year before. In Baxter’s obituary in the Independent, the politician Tam Dalyell called the win "miraculous" and, identifying his subject as its source, referred to Baxter as "sublimely skilful".

A year later, this time at Wembley, he was part of an even more unlikely 2-1 win – the second tenet of his legacy. The Press Association aren’t known for breathless flair in their reporting, but they were captivated.

“…the new-born riot of self-expression that bubbled freely from Baxter, (Dave) Mackay, (John) White and (Denis) Law, the all-important quadrilateral that formed the heart of the Scottish effort."

But perhaps the performance which really retains its gleam comes – ironically – from the shadow of Baxter’s own decline.

By 1965, his relationship with Rangers was close to fracture. His frequent brilliance in spite of a decadent, nocturnal lifestyle had convinced him of his talent’s invulnerability and, unfortunately, the club did little to dissuade him of that assumption. He was indulged in ways that other players weren’t and had an aversion to nurturing his gifts that was never properly challenged.

John Greig, who would captain Rangers and whose statue now stands outside Ibrox, recalled the ‘times when (Baxter) came into training that he couldn’t bite his fingers and he would just go through and lie in the bath trying to recover.’

Symon, by all accounts a disciplinarian, made exceptions for his No.6. The club did too. Baxter’s bar tabs from around Glasgow would be sent to the club and Rangers seemed prepared to turn a blind eye to his life’s hedonistic blur – or did, until Baxter wanted more money.

He had grown irritated by his salary. A fully-fledged international, who would also appear for Rest of the World sides, he would regularly mix with players earning far in excess of his £35 a week. In particular, the disparity between what a parsimonious Rangers board would pay and what could be earned south of the border rankled and would help to create an impasse.

It was one which occurred at the most inopportune moment. In a game against Rapid Vienna in Austria, in the second round of the European Cup, Baxter suffered that broken leg at the end of a tie which was already won.

At the end of the season he would be sold to Sunderland, one of the few English teams who weren’t deterred by his reputation. Two fruitless years later, he would move further south, down to the City Ground and Nottingham Forest, but making one final stop at Wembley first, for a very last dance.

By far the most famous footage of Baxter comes from April 1967, and a European Championship qualifier that Scotland would win 3-2. The visitors had the lead and the command of the game in the second half and Baxter, framed on the far touchline, juggled the ball towards a phalanx of England defenders, before sending an impudent flick over their heads and into the stride of Denis Law.

This was world champions England. This was Banks, Moore, and Charlton's England and, as Kenneth Wolstenholme observed on commentary, Baxter "was taking the mickey".

It was outrageous and ridiculous, provocative and cheeky. It was also symbolic. Way back in footballing antiquity, all the skill came from Scotland. English football was polluted by the direct and brutish corruptions of the game played in the public schools. North of the border skill was still king and there at Wembley, decades after those differences had stopped being relevant, was Baxter as their cipher.

His end was still near, though. In photographs taken at full-time, when Scottish fans had invaded the pitch and one was caught, draped around Baxter’s neck, it wasn’t a Slim Jim anymore. He was thicker, his jowls were heavier. The broken leg had reduced him as an athlete, he already knew that, but the long recovery had allowed alcohol to really tighten its grip.

Forest would be the nadir and the stories are legendary and awful – of bars and bets and being found badly beaten in the street.

He appears briefly in The Footballer Who Could Fly, Duncan Hamilton’s memoir. In it, the author describes a chance encounter between Baxter and his father, who was then working as a barman in Nottingham.

Baxter had just moved to Forest, in what would become one of the most notorious transfers in the club’s history, and he’d fluttered into a local bar.

My father noticed the shoes first: the sheen of expensive leather and the slenderness of the toes, which were cut into the sharpest points, each glinting like the top of a chef’s knife.

He came into the pub and sat on a high wooden stool, as if he owned the room. My father watched lay the flat of his hands on to the bar. He ordered a bottle of Bacardi and a jug of Coke, and asked for a small bottle of ice.

He would leave on a free transfer.

His football career would be over at just 31. A return to Ibrox, almost on compassionate grounds, ended his misery in England, but his second verse would last just a few short and unhappy lines. He would retire in 1970.

He divorced and remarried. He took the license of a pub. By 55 he needed a liver transplant. At just 61 he was dead, succumbing to pancreatic cancer.

Ten days before he died, he recorded an interview with Chick Young which, until very recently, could be found online. It was Baxter at his most charming. He laughed and giggled and, improbably, his eyes still danced when he spoke of his yesterdays. It’s moving television. It’s a man who knows he hasn’t got much time, who isn’t afraid of his regrets, but who is comfortable with the effect he’s had and how he’ll be remembered as a footballer.

Rightly so. Eleven days later, the day after he passed, a banner was unfurled in the stands at Hampden Park during the semi-final of the 2001 Scottish Cup.

It read: “Slim Jim. Simply the Best”.

It was in the Celtic end.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!

NOW READ…

SCOTLAND How Graeme Souness kick-started a Rangers revolution

QUIZ Can you name the last XI every Premier League side put out?

DEAL Three ways to (safely) get FourFourTwo magazine right now – with special offers

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.