Jorge Valdano: My Secret Vice

"Football was always considered to be an almost animalistic expression of society. I disagree..."

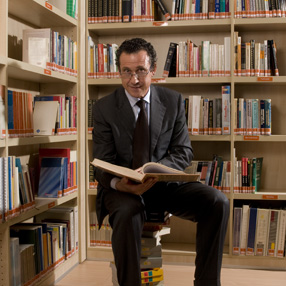

I was born in a town where there was no library and in a house where there were no books. I started building a library based on intuition because there was no one around to guide me. If you want to see a self-taught man, look at me.

The first book I read was The Picture of Dorian Gray, which came free with a magazine. I read many magazines, including kids’ magazines. Even [sports magazine] El Grafico. I didn’t realise at the time that it was very influential; the writers ended up teaching generations of journalists. Some were more literary, others more tactical, but each point of view was always deeply considered.

Matches were played on Sundays and the magazine came out on Friday. Nowadays that would be impossible – an article talking about last Sunday’s match might as well be talking about last year – but in those days it gave them time to write. It was almost a sociological analysis of what goes on around football, and was always an attractive read. Going to the barber’s, as the writer and cartoonist Roberto Fontanarrosa used to say, had a distinct perk: that’s where a month’s worth of El Grafico could be found.

Then I moved to Rosario, to join Newell’s Old Boys. Recently, someone who also lived there told me he remembers me always with a book in my hand. I didn’t want to learn, or know more. I wanted to have fun and this was a different way of having fun – more rational, less emotional than football. More individual, less collective.

There was also a sense that reading distanced me from football and broke my concentration. I once had a conversation with Carlos Bilardo before a match at the 1986 World Cup finals: “What are you doing reading?” he said. “I need it to relax,” I replied. “You don’t need to relax,” he said. “But I get too nervous otherwise,” I said. “You have to be nervous,” he said. “But I’ll go mad,” I said. “You have to go mad” he said. Bilardo felt that to take away some of the madness from fooball was tantamount to taking away the due attention it deserved. But for me it was a necessity to read, precisely because I lived football with such obsession so I needed to bring down the level of tension and enter other lives, other times, other worlds.

Ours was a world made of football: we lived in [Mexican club] America’s training ground, in rooms surrounded by football pitches, with football press, football players, football conversations. This monothematic universe was too much for me. I started a small black market – some friends would leave me a newspaper with a guard I had ‘bought’.

In those days there weren’t many connections between general culture and football. Only a few intellectuals took an interest in football. Others were clearly opposed to it, such as Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (“what can we expect of a society that started playing chess and ended up playing football?”). Football was always considered to be an almost animalistic expression of society. I disagree. To ignore something that can move masses is undignified for an intellectual. Football is the perfect field for delving into comedy and drama, and to search within it gives enormous opportunities for literary play. But what we now consider a modern development – the intellectual discussing football – is the oldest thing there is. It goes back to Ancient Greece where the harmony between mind and body was the highest expression of happiness.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

When I moved to Spain my vision of football was transformed by Manuel Vazquez Montalban. I’ve always thought of football as being deeply engrained in life, but I would never have been able to discuss it without his influence. I started writing while at Real Madrid. One Easter, the Spanish newspaper El Pais published a short story of mine, which I had written while travelling with the team to a European Cup match against Bayern Munich. Intellectual magazine Occidente then published my essay Stage Fright. No footballer had ever published in that magazine before, and so I became the bearded woman of the circus. In a sense: every player needs to be identified and, well, I became known as The Intellectual. My book, Dreams of Football, was published while I was at Tenerife and sold very well. The publisher then invited me to edit a selection of intellectuals’ views on football.

Literature is not an alternative to football but a complement. As a writer I am more formed by myself as a reader than myself as a footballer. Football is more like music: what comes out cannot be repaired; action and reflection are simultaneous. By contrast, in literature the search is more intimate and much longer. What can I say? I find that laborious search pleasurable.

From the April 2009 issue ofFourFourTwo.