Jose Mourinho at Chelsea: how the Special One changed the way I watch football

Jose Mourinho’s 2004 appointment at Chelsea proved to be a perfect synergy between club and manager, money and ambition, man and moment. Clive Martin fan reflects on how that title-winning season and style of football will live on forever

Like a lot of English football fans, the first time I ever heard about Jose Mourinho was during the build-up to Porto’s Champions League last 16 match against Manchester United in 2004.

The British football media often cast continental opposition as either dangerous bruisers or walkover Johnny Foreigners – but there was something a bit different at play here. An odd amount of press time had been dedicated to Porto’s manager, a young upstart of considerable pedigree. Listening to a football phone-in on the morning of the second leg as I walked to school, I vividly remember one caller saying, “Don’t underestimate Porto, they could really do United here” – a notion that seemed to fly in the face of empirical wisdom of the time.

By the end of that game, English football had been rocked. The image of Jose pelting it up the Old Trafford touchline, fists in the air, Prada coat flapping in the wind, was instantly transmitted around the world.

Daring to do such a thing inside Old Trafford, the Theatre Of Dreams, the Fergie Time Arena, was tantamount to sacrilege – a momentous show of disrespect in the Premier League’s Mecca. But non-United fans couldn’t get enough of it. They had found a glamorous, funny, sexy football iconoclast in the form of the man who’d desecrated the holy ground.

Here was a gaffer who wasn’t a 60-year-old from Govan with a broken nose, or a bookish Frenchman, but one who looked like he’d been pulled from a TAG Heuer advertorial in a magazine you can only buy at airports.

His Porto team continued their form all the way to the podium, dispatching an equally fancied Monaco team with ease in the final. Mourinho had reached the pinnacle of European football with a team that appeared to be in the right place at the right time – a perfectly-balanced combination of unknown quantities, future superstars and last-chance saloon patrons that have been hallmarks of every surprise package from Leicester to Ajax and beyond.

That summer, 15 years ago, was one that would shape my footballing life to come – for better or for worse.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Seeing Mourinho for the first time, charming the cameras with his grandiose statements and coquettish misinformation, was a feeling I can only liken to seeing your next nightmare ex across a crowded room.

Of course, he was always off to Chelsea – the appointment was a perfect synergy between club and manager, money and ambition, man and moment. The name, the locale, and the recently-acquired big-stage clout all suited this former PE teacher from Setubal to a tee.

From a caravan park in Brittany, I remember keeping abreast of the latest stories as they appeared on France 24 and in day-old English newspapers. He’d set about negging his way into the hearts of the moustachioed football media like a suave personal ad conman. They enjoyed the natural Brian Clough comparisons, and the endorsement from the man himself.

Even more excitingly for me, he was signing some of his successful Porto players, including indomitable central defender Ricardo Carvalho. He also acquired Didier Drogba, the butcher of Marseille, and a young Dutchman called Arjen Robben who was supposed to be quite good. He was rumoured to have made an audacious bid for Liverpool’s Steven Gerrard and started referring himself as “a Special One”, much to the astonishment of the tweed blazer brigade. It was my Year 11 prom that summer and I chose to wear my suit open-necked, without a tie, as that’s what Jose did. He hadn’t even managed a game yet.

Mourinho soon set about English football like the Red Army marching through Smolensk. Manchester United, already rattled by him in the Champions League, were unable to cope with another viable title contender. They lost their opening game of the 2004-05 season to an Eidur Gudjohnsen goal at Stamford Bridge and finished 3rd, 18 points behind the Blues.

Arsenal, arguably too caught up with their ‘Invincibles’ status, were beaten into 2nd by a team largely assembled at the start of the season, and sent into a downward spiral that has yet to come to end.

Admittedly, the goals weren’t exactly flying. Drogba failed to convince in his debut season, Mateja Kezman was useless and the football was about as liquid as a Calippo at the bottom of a Londis fridge. However, the tenacity and physicality of that team was near-impossible to best. In the simplest terms, Mourinho’s team were hard, but not in the Razor Ruddock or Terry Hurlock manner that English football was accustomed to.

Jose’s boys could run as well. Captain John Terry later shed some light on the methods their incredible match fitness was built on. “He brought three young lads in as ball boys,” he said. “Every time the ball went out of play, we had a ball back in instantly. If there was a bad pass or a bad roll from one of his staff, he would stop the session and go berserk.”

The purists (read: Arsenal fans) didn’t seem to appreciate it, but this was football without the fat on; lean, mean, elemental. The best games in Mourinho’s first season at Chelsea were backs-against-the-wall thrillers – rarely comfortable, but never in doubt. It might have been 1-0 football, but it was played with such feeling, such intensity, that the tackles felt like goals anyway. The team was built on almost clichéd military values – hunger, leadership, teamwork, masculinity. Terry in particular took to the system like a leopard to a gazelle, and became Mourinho’s dressing room Luca Brasi.

“If we were losing a game you didn’t want to be in the dressing room,” said later-arrival John Obi Mikel. “The manager would speak and then leave it to JT to carry on. He smashes the whole place up and then we go back out and get the win.” With management techniques like this, it’s little wonder Jose struggled with a squad of Instagram-famous ‘ballers’ at United.

At the heart of it, the success was Mourinho himself – raging on the touchline, swearing at referees, infuriating adversaries, introducing the term ‘parking the bus’ to football’s lexicon, and loudly redefining masculine sexuality via his appearances in adverts and on magazine covers. He was, quite simply, on one.

Looking back at it all now, it was some time to be a 16-year-old Chelsea supporter, yet its legacy is hard to contend with now the dust has settled and the game has changed. That season, that brand of football and that way of looking at the game would never leave me. Because it was so potent, because it happened at such an impressionable time in my life, it formed the basis of my football understanding, even as that became more of a minority view. And because despite my better instincts, I’ll always be a Mourinho man, just as watching The Beatles play at the Cavern Club will always make you a Beatles man.

As much as I try to appreciate styles other than the one I came of age with, and accept the flaws of players with slightly more effete, possessive tendencies, I’ll always be moulded in that shape even though I’m aware I should know better.

The truth is that I’ll always prefer a ravenous midfield engineer with a yellow card or 10 in him to a short-pass conductor. I’ll always want to see centre-backs who fight for every ball, and goalscoring midfielders. I’ll never truly take to tiki-taka, just as I’ve never truly taken to Pink Floyd or Cluedo.

To be honest, I never really saw the point of Xavi. I’ll always, always insist Frank Lampard was better than Gerrard, and I applaud clearances. There will always be an inherent violence to my football, because I was raised with the pure ideology of Mourinho.

It’s a mindset that often shows you as a bit of a regressive stick-in-the-mud, yet one which often prevails at the same time.

When I first heard about Julian ‘the Puffa jacket manager’ Nagelsmann’s anti-tackling policies at Bundesliga club Hoffenheim, I took it as something of a personal affront – a spit in the eye of everything I found to be decent, like a Middle England car dealer flipping his lid when a Jeremy Corbyn leaflet comes through the door. It was even more distressing when Nagelsmann was linked with the Chelsea job.

For many Blues fans, the inherent distrust of Maurizio Sarri was birthed here. The Italian was about as far away from the Mourinho ideal as you can be without being Nagelsmann. Sarri players didn’t shoot from distance. They didn’t hoof the ball upfield. They only really beat sides they should beat and he conducted his post-match press conferences with all the candour of a mafia accountant in court. Sarri appointed a fairly lightweight sideways pass merchant in his old Napoli favourite Jorginho, where once there was Claude Makelele.

The impact Mourinho had at Stamford Bridge isn’t just felt in the trophy room – it’s woven into the fabric of the club and any other cliché you might care to mention. Managers and players are either ‘Chelsea men’ or they aren’t. It may sound quite reductive, and in many ways it is, but everyone needs something to believe in.

Being a disciple of Mourinho and a follower of the modern game is a frustrating experience, not unlike being a Liberal Democrat or Metric Martyr. Quite simply, the values you believe in are just deeply unfashionable. The histrionics, the insults and blame-game management are almost beneath contempt in a tactile, tactical, manager-as-trendy-vicar era – an Emerson, Lake & Palmer T-shirt in 1977.

Watching Manchester City and Liverpool change the way the league plays is like seeing the magic money tree build new hospitals when you were brought up to believe in austerity.

As we later saw, the Mourinho belief system presents a number of problems, chief among them the man himself. The problem is, Jose isn’t done yet – he isn’t a permanent banner on the stands, a statue outside the ground or a strange retired godhead like Kenny Dalglish or Alex Ferguson. He’s still a living, working manager and occasional pundit, who can still embarrass, enrapture and enrage the football universe.

His tenure at Old Trafford didn’t cover anyone in glory – not him, not his Chelsea disciples, not the club itself. In fact, it arguably ranks as one of the most painful managerial reigns ever; a protracted saga of minor trophy wins, ideological impotence and Scott McTominay.

But after a few years looking like a divorcing stockbroker, living in a hotel and single-handedly trying to destroy the concept of the influencer-footballer, Mourinho eventually returned to somewhere near his best. Not in the dugout but the studio, where his lucrative appearances have become must-watches. As he charms his way through the plasma, the ashen-faced bastard who benched Real Madrid legend Iker Casillas, screamed at Chelsea doctor Eva Carneiro and told Rafa Benitez’s wife to ‘look after his diet’ now seems like a completely different person.

That famous golden, cheeky glow is back – he’s funny, poised, controversial and shaving properly again. Yet most interestingly, perhaps, he’s started to share the love.

A quiet, but fascinating sea-change moment occurred while he commentated on Liverpool’s sensational Champions League dismantling of Barcelona at Anfield. Mourinho, instead of blaming the result entirely on Gerard Pique and Sergio Busquets’ defensive mentality, opted to lay the plaudits at Jurgen Klopp’s feet.

“This has one name – Jurgen,” he said with the grace and respect of an ageing title-holder who knows he’s been beaten by a better man. Although, as the managerial merry-go-round clicked into gear again, Mourinho couldn’t help but take a swipe at the Liverpool boss, saying he had “won absolutely nothing”.

Still, this was a stark contrast to his previous psychic smoke signals towards Klopp, making the German out as a buffoon and mimicking his gesticulations. That moment felt like a shift of sorts, a slightly-too-late passing of the baton and admission that, really, it’s all fun and games.

Beyond that, it revealed to me something I hadn’t considered before: that there’s more Mourinho in Klopp than you might think, and vice versa. The way Jurgen has charmed the English media – swearing in his post-match interviews, taking everything on his shoulders and letting the players play – is straight out of the early-Mourinho playbook. Klopp just carries it out in a smiley, upswing way, whereas the wrongs of Jose loom far larger than his rights in our collective memory.

The Portuguese is often cast as a grumpy, problematic, argument-prone alpha, and there are many examples to suggest he is. But he is also charming, honest, revolutionary and loved by those who believe in the way that he looks at things.

His style of football may be outdated and his stock might be lower than ever, but Mourinho’s influence on the game is still felt in ways that go beyond simply knowing how to set up a back four.

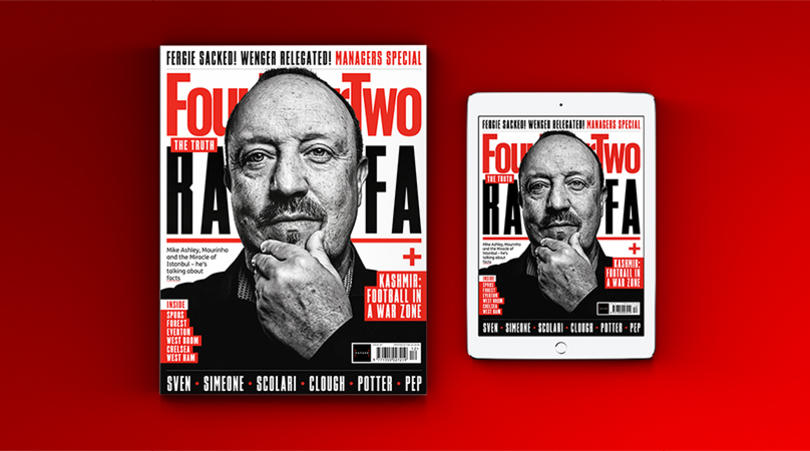

This feature originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe today! The world’s greatest football journalism for just £9.50 every quarter

NOW READ...

COMMENT Could this weekend's game against Manchester City be the making of Frank Lampard's Chelsea?

QUIZ! Can you name every Premier League team's last three captains?

WATCH Premier League live stream 2019/20: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world