Jose Mourinho's quest for Champions League history: the 6 games that defined his search for greatness

Mourinho could become the first manager to win the competition with three different clubs. But 10 long years have passed since he last won it, and now RB Leipzig stand in his way

This article first appeared in the March 2020 issue of FourFourTwo. You can subscribe to the magazine now and get every issue for less than £3.80, plus free bookazines worth £29.97!

In many ways, Jose Mourinho and Sir Walter Raleigh have always been alike.

An experienced explorer of foreign lands, Raleigh spent years in search of El Dorado. The lost city, allegedly laden with gold, was a legendary location throughout the Spanish Empire. It was believed to be somewhere in South America, and numerous adventurers had tried to find it. Raleigh may have been from Devon, but he fancied a go as well. During the middle of the Anglo-Spanish War, he sailed west to Trinidad, captured a Spanish governor and grilled him for information about the previous expeditions to El Dorado. In 1595, Raleigh set off up the Orinoco river in neighbouring Venezuela.

Mourinho has repeatedly likened his quest to win Europe’s greatest club competition with this pursuit for the fabled city. “The Champions League is El Dorado,” he’s said – and he doesn’t mean the failed BBC soap opera.

He has sampled El Dorado’s riches twice before. The last time was now a decade ago, when Inter beat Bayern Munich in 2010’s final. Mourinho burst into tears as Howard Webb blew for full-time in Madrid’s Bernabeu. He’d become only the third manager to win the European Cup with two clubs. Ernst Happel had been a manager for 21 years when he achieved it; Ottmar Hitzfeld, 18. Mourinho did it in just 10. In that moment – beaming with joy, holding the matchball as a souvenir, son perched on his shoulders – Mourinho had everything he ever wanted. Yet his ambition wasn’t sated. “I want to be the only coach to win the Champions League with three clubs,” he announced that very night, confirming he was leaving Inter: destination, Real Madrid.

Ten years on, he’s yet to achieve that dream, and there are major doubts he ever will. Mourinho has drifted further and further from more Champions League glory, in a decade of drama, disputes and disappointments. It’s six years since he even won a knockout tie. If Spurs lose to RB Leipzig in the last 16 of this season’s competition, it could be two years or more before their boss gets another chance.

Now 57, is it all over for Mourinho as a Champions League force? Given Tottenham’s past six months, no one expects his new side to progress far. But then, not many fancied Porto or Inter, either.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

PORTO vs MANCHESTER UNITED 2004

“I understand why Ferguson is emotional – you’d be sad if your team was dominated by an opponent on a tenth of the budget”

For Vitor Baia, Mourinho’s ascent to Champions League stardom really began on December 12, 2003.

That morning, goalkeeper Baia and the rest of Porto’s squad were huddled around a television at their training ground in Vila Nova de Gaia, waiting to discover their opponents in the last 16. The draw provided a daunting answer: Manchester United. “Mourinho started jumping in a festive mood,” Baia tells FourFourTwo with a smile. “He said, ‘Finally, a proper rival for us! Finally, a decent challenge. We’re going to beat them!’ We were shocked – we didn’t understand that happiness, because we were apprehensive when we drew United. But then we thought, ‘OK, the boss is happy – we can make it.’ Right after the draw, Mourinho started to work on those games.”

Mourinho’s Champions League debut as a manager had come at the Bernabeu two seasons earlier against Real Madrid’s Galacticos, having taken over Porto midway through the 2001-02 campaign. “Only a gun will stop Real Madrid,” he said – though his side nearly did it without recourse to firearms, losing to a late Santi Solari goal.

Porto’s performance in Madrid gave encouragement to a team who had lost to Barry Town in one leg of a qualifying tie earlier that season, under Octavio Machado. Porto were 5th in the Primeira Liga when Mourinho began. “I remember his first speech to the squad,” says Baia, who’d worked with his new boss during Mourinho’s time as assistant at both Porto and Barcelona. “He said we were probably too far behind to win the league that season but we’d definitely be champions in the next one. And guess what? It happened.

“Even at Barcelona, we could see that young man was special. Louis van Gaal trusted him to research opponents – in pre-match team talks, Mourinho would tell us how they would play. The way he spoke was somehow different from everything I’d seen before. Did I think he’d be a top manager? Yes. Honestly, I saw it coming.”

But Baia got a surprise eight months into Mourinho’s Porto reign, when the keeper was suspended from the squad. “I was shocked,” admits Baia. “I mean, we had an argument, but it was strategically created by him, and that argument resulted in my suspension. He knew me really well. One day, he provoked me, sure that I’d react.

“But now, I understand what he did. He was a young manager; I was an experienced player who knew him very well. We actually had a social relationship off the pitch. He wanted to show everyone I wasn’t special; that I was just another member of the group. So, he created that situation. It was a strategy, and it worked perfectly.

“A month later, he requested my presence in his office. He simply asked if I wanted to play the next match, at Austria Vienna. I said I was keen, and he told me to get ready for it. I came back as the first-choice keeper, the position I had left a month before.

“Mourinho is a very, very intelligent man. He is a proper leader. Even when he creates a situation, his only thought is to make the team stronger. That episode was his emancipation as a manager. He put me in a complicated position, but it left me full of energy to prove there’d been a misunderstanding, and it was a clear message to the rest of the squad: they’d be punished for any mistake. From that moment on, leadership had been achieved, and he could show his talent as a football manager.”

On course for a second domestic title in a row, Mourinho recruited teenage forward Carlos Alberto from Fluminense in January 2004, ahead of the clash with Manchester United. “I was very young and he made me feel comfortable in the group,” the Brazilian tells FFT. “He asked which number I would like. I asked for No.10 and he said, ‘That number is taken, but you’ll wear No.19 – one plus nine is 10. Take it and we’ll be champions together.’ I liked him from day one.

“Early in my time there, [defender] Jorge Costa told me that Jose wanted to speak with me before a session. I went to the pitch from the changing room, but some of my team-mates were hiding in the tunnel and threw cold water on me. It was winter in Portugal – really freezing! Mourinho had planned the joke with the rest of the group. He was fun to be around.”

When the first leg against Manchester United arrived, the squad were ready to get serious. Porto were playing their first European tie at the newly-opened Estadio do Dragao, and two Benni McCarthy goals gave the hosts a 2-1 victory. A smiling Mourinho held out his hand to Alex Ferguson at full-time, but the Scot refused to shake it, believing Porto play-acting had resulted in Roy Keane’s late red card. Mourinho wasn’t afraid to snap back, even at a managerial legend. “I understand why he is a bit emotional,” offered the 41-year-old. “You’d be really sad if your team gets as clearly dominated as that, by an opponent built on maybe 10 per cent of the budget.”

It prompted Ferguson to criticise Porto’s antics further, before the second leg. “It was up to me to convince my players he was scared of us,” Mourinho later said. “It was a psychological game between two coaches. I had to show the players that I wasn’t afraid of him.”

The message reached his squad. “Mourinho was never intimidated by anyone – so if it had to be Sir Alex, no problem,” explains Carlos Alberto. “It’s like when you’re a kid and your father is a leader. You look at him, he shows a strong personality, and you grow up to be a confident person, knowing what you want and how to fight for it.

“That’s what Jose did for us in 2004. He would defend his players until the end, no matter what. That episode with Ferguson gave us a lot of confidence to beat United.”

And they did, Costinha pouncing on Tim Howard’s 90th-minute mistake at Old Trafford to prompt Mourinho’s delirious sprint down the touchline. “I’d been subbed, so I ran to join him,” says a smiling Carlos Alberto. “What an unbelievable moment that was.”

The night before the second leg, Liverpool had expressed interest in meeting Mourinho at a nearby hotel, as they considered options for Gerard Houllier’s replacement. After Porto defeated Manchester United, Chelsea showed interest. Two months later, Mourinho was a European champion, thanks to a 3-0 win over Monaco in the final. “That team had the face of Mourinho,” adds Carlos Alberto, who scored in the final. “I don’t think we could have done it without him.”

CHELSEA vs BARCELONA 2005

“In 200 years, Barcelona have won the European Cup once; I’ve been managing for a few years and I’ve won the same amount”

With hindsight, a couple of clues gave it away that Mourinho was lying. “Do you want to know the team?” he asked during his press conference at the Camp Nou, a day before the first leg of Chelsea’s last-16 tie against Barcelona, in his first season as Blues manager. He was ready to give his performance.

“I can say my team and Barça’s team. Referee: Frisk. Barcelona: Valdes, Belletti, Puyol, Marquez, Giovanni, Albertini, Deco, Xavi, Eto’o, Giuly, Ronaldinho. Chelsea: Cech, Paulo, Ricardo, John Terry, Gallas at left-back, Tiago, Makelele, Frank Lampard and Joe Cole… Drogba i Gudjohnsen,” he added, pausing briefly before accidentally using the Catalan word for ‘and’. This display was for Barcelona’s benefit. The Barça team he predicted was spot on. Chelsea’s was a lie.

“It’s a good finish,” he said, springing to his feet and attempting to march merrily out of the room, satisfied with his mischievous work. It would have been perfect, if he hadn’t walked towards a broom cupboard. The door wouldn’t open, and he had to turn around and leave another way. Still, at least the plan worked.

“I’d been struggling with injury and Jose told me, ‘You’ll be playing, but I’m going to announce a different team’,” Damien Duff told FFT. The winger started instead of Eidur Gudjohnsen and quickly set up a crucial away goal. Didier Drogba was sent off as Barcelona came back to win 2-1, but the result kept Chelsea in the tie.

“It was a tactical match because of Mourinho’s smartness,” says Glen Johnson, who came on as a substitute that night. “He arrived with a bang. He instilled massive confidence in everyone. That’s why we blew the Premier League away that year: if you get good players believing they’re good, they’re going to be unstoppable.

“If I could pick one thing that impressed me, it’s how he delivered meetings: straight, simple and clean-cut. He knew exactly what he was going to say. He was very good at setting up a team against an opponent who were favourites, with your backs against the wall.”

He was very good at getting under Barça’s skin, too, jibing at their European Cup record and griping about a supposed conversation between coach Frank Rijkaard and referee Anders Frisk at half-time in the first leg. “When the game is finished, the next one has already started,” Mourinho once said. Frisk received death threats and soon announced his retirement. UEFA were furious. So was Rijkaard. Rattled by the mind games, Barça fell 3-0 down within 20 minutes in the second leg, to a Chelsea side rampant on the counter-attack. In a manic first half at Stamford Bridge, Ronaldinho brought it back to 3-2 with a penalty and a magical toe punt, and Barcelona were winning on away goals – until John Terry headed Chelsea through.

While Rijkaard and players jostled with stewards at full-time, Jose raced onto the pitch and jumped onto the back of 24-year-old Terry, his captain. For human behaviour expert Desmond Morris, that was a telling insight into the nature of that relationship.

“I disagree with the portrayal of Mourinho as a father figure,” he explained. “He’s more like an elder brother – you couldn’t imagine Alex Ferguson or Arsene Wenger jumping on a player’s back.”

Chelsea didn’t lift the trophy that year, denied in the last four by an infamous ghost goal at Anfield, but the Barça tie was arguably the first time they’d beaten one of Europe’s elite in the Champions League. When they’d reached the semi-finals under Claudio Ranieri a year earlier, their biggest scalp had been domestic rivals Arsenal.

“The Barcelona win put us on the map, because they’d been one of Europe’s top teams for many years,” says Johnson. “The fact we could land a punch on them proved we deserved to be at that level. We were probably the best team in Europe at that time.”

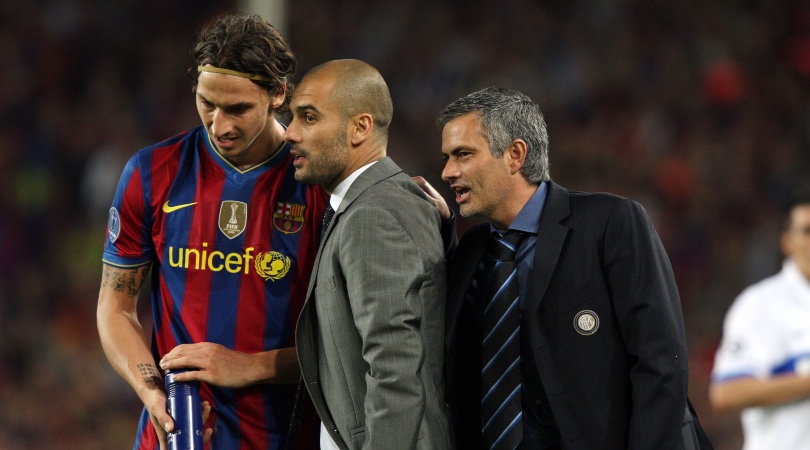

INTER vs BARCELONA 2010

“If you have a Ferrari and I have some small car, I have to puncture your tyres or put sugar in your petrol tank”

Five years later, Mourinho was back at the Camp Nou – stood alone in the stadium chapel, weeping uncontrollably. Minutes earlier, he had experienced possibly the most emotional moment of his career; the moment that perhaps defines him above all others. He had just helped Inter to their first European Cup final since 1972.

The Nerazzurri were on course for their fifth consecutive Scudetto, but in that time they had progressed no further in the Champions League than the quarter-finals – ‘a psychological wall’, as Mourinho put it. He recruited the players he needed to challenge for glory in Europe: Zlatan Ibrahimovic had been lured to Barcelona but in came Samuel Eto’o, Wesley Sneijder and centre-back Lucio, whom Mourinho turned into a pure defender.

“Jose didn’t like it when I took the ball and dribbled forward, which had always been my style,” reveals the Brazilian, smiling. “To this day, I still thank him for his advice. At Inter, I managed to get into FIFA’s best XI of the year. The way he pushed me was responsible for that. He’s the best manager I’ve ever had.”

As with Baia at Porto, Mourinho was successful in exercising control over his squad.

“Mario Balotelli had a big argument with Mourinho during training – they were cursing each other,” Lucio explains to FFT. “Mourinho said, ‘Until he comes to my room and apologises, I’ll leave him out of all matchday squads from now on.’

“Balotelli refused, and that situation lasted for a couple of months. We were always encouraging Balotelli to talk to him, saying, ‘Mario, don’t be so proud.’ There was no way to convince him, but then we started getting close to the Champions League semi-finals. We said, ‘Mario, are you going to lose all of these matches because of pride?’ He finally called a truce and spoke to Mourinho. Within a week, he was back in the squad.”

Balotelli, 19, came on as a substitute as Inter beat Barcelona 3-1 in the first leg of the semi-final. Barça, forced to travel to Milan by bus, hadn’t been helped by the ash cloud blanketing Europe after the eruption of Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull, but they were simply outmanoeuvred by Mourinho that night.

“Everything was around not letting Lionel Messi play,” the manager later said of his strategy. “After the game, the press used the word gabbia – a jail – for Messi, because we didn’t play man-to-man. Javier Zanetti, Thiago Motta, Esteban Cambiasso – everyone was responsible for any position that Messi could go into. Then the strategy was to hurt them by going strongly with four or five players in attacking transition. We were at home: we needed to win. It’s hard to say it when we had only 30 per cent possession, but we were totally in control.”

They were in control of the tie, too, even if their task in the return leg was complicated by Motta’s 28th-minute dismissal at the Camp Nou. From there, the visitors produced one of the most remarkable backs-to-the-wall performances in Champions League history. “People claimed Mourinho was a defensive-minded manager, but after winning the first leg 3-1, why would we need to go to the Camp Nou and beat them again?” Lucio asks FFT. “What we had to do was rely on what we’d done in the first 90 minutes, hold the game and seal our place in the final – and that’s what we did. It’s already very difficult to play there, so imagine that with a man down. Were we going to attack them? Of course not. We defended our goal.”

Defend it, they did. “We didn’t park the bus, we parked the plane,” said Mourinho. Gerard Pique scored late on, but it wasn’t enough. Two years earlier, Mourinho had told Barcelona they were wrong to choose Pep Guardiola, not him, as their boss. Now he was charging across the Camp Nou pitch, finger in the air, having eliminated his former employers and led Inter to the final at the Bernabeu.

In the home dressing room, an apoplectic Ibrahimovic ripped into Guardiola – but Inter’s ageing squad had given their all for Mourinho. Even Eto’o sublimated his ego to play as a virtual full-back late on. Weeks later, Jose outwitted former Barcelona coach Louis van Gaal, Inter beat Bayern Munich 2-0, and he had his second Champions League trophy. “My greatest achievement? To win the Champions League with Inter,” he has since said.

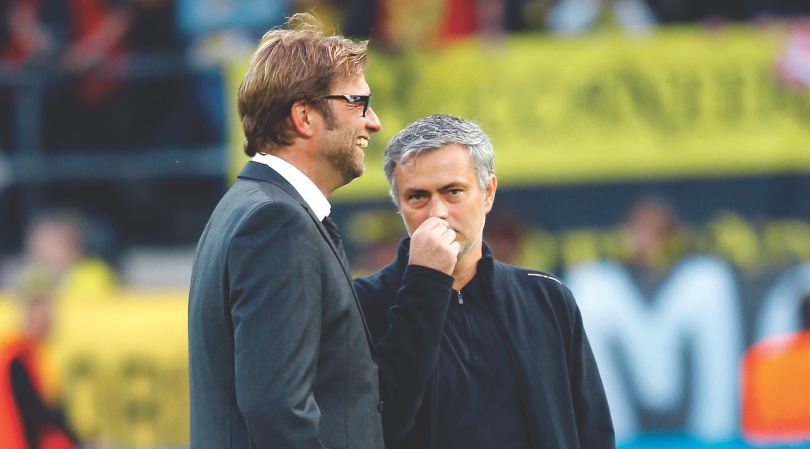

REAL MADRID vs BORUSSIA DORTMUND 2013

“In Spain, some people hate me”

On the morning of his club’s Champions League semi-final at Borussia Dortmund in 2013, Real Madrid president Florentino Perez got into a conversation with some journalists at his hotel.

Madrid were 13 points behind Barcelona in the league, and Mourinho’s relationship with the club’s stars had deteriorated. Still, Perez backed his manager. If there was any issue, he told the journalists, it was the fault of the players – Mourinho, now nearing the end of his third season, had simply been trying to shake them out of their complacency. It was difficult to manage a team full of superstar egos, the president insisted, whereas Dortmund were “a team of children” managed by “a child’s coach”. Perez was convinced that Madrid would beat Jurgen Klopp’s side.

He had hired Mourinho to finally deliver La Decima, Real Madrid’s fabled 10th European Cup, in 2010. So relieved was Perez by Inter’s victory over Barcelona – denying the Catalans the opportunity to win a Champions League final at the Bernabeu, Real’s worst nightmare – he had agreed a deal with Mourinho straight away.

Days after winning the final with Inter, Mourinho took a stroll with Perez through the Bernabeu museum. The pair passed the European Cup. “I miss it,” said the Madrid president. “I miss it, too, and it’s only a few days since I won it,” replied Mourinho.

In his first season at the helm, Real Madrid thrashed Tottenham to reach their first semi-final since 2003. There, Mourinho was denied by Barcelona’s revenge. He had ramped up the Clasico rivalry to such a toxic level that it all spilled over. In the first leg, at the Bernabeu, Pepe was sent off, Mourinho followed him, and Messi scored twice in the final 15 minutes to give Barça a 2-0 victory. Mourinho blamed German referee Wolfgang Stark, hinting officials somehow always favoured Barça. Pepe stormed into Barcelona’s dressing room after the match, sparking a brawl.

Madrid’s stars, Cristiano Ronaldo included, had been infuriated by Mourinho’s plan to play for a 0-0 draw at home. Such tactics may have been acceptable at Porto or Inter, but not at Real.

Things got worse when Mourinho outlined his plan for the second leg: to play for a 0-0 draw again. “If it ends 0-0, we can say the tie was decided by the ref in the first leg,” he told a disbelieving squad, according to Diego Torres’ biography, The Special One.

A heated discussion ensued between Mourinho and Ronaldo, as club advisor Zinedine Zidane watched from a corner of the dressing room. Forty minutes into the meeting, Mourinho asked Zidane what he thought. “You’re very good players and you should try to beat Barcelona,” said Zizou. “We are Real Madrid. Real Madrid always go to win.” Mourinho walked out of the room. Los Blancos drew 1-1 at the Camp Nou. A year later, they won La Liga with a record 100 points and 121 goals, and Mourinho signed a new four-year deal, but La Decima eluded them once more. Real again lost in the semis, beaten by Bayern Munich on penalties with misses from Ronaldo, Kaka and Sergio Ramos. Mourinho reacted to Ramos’ ballooned effort with cartoonish incredulity.

In 2012-13, tensions erupted as Barça ran away with the league. “The relationship with some key players was difficult: Ramos, Pepe, Cristiano and Iker Casillas, who was relegated to the bench,” says Marca journalist Jon Prada. “He had problems with the press. Half of the supporters didn’t like him. They were divided about Mourinho.”

Yet Perez blamed the players, and told journalists this before the Champions League semi’s first leg. That afternoon, they got wind of what he’d said. That night, with Diego Lopez and not Casillas in goal, a downbeat Madrid were overwhelmed by Dortmund’s gegenpress and Robert Lewandowski, who scored all four goals in a 4-1 victory.

A 2-0 victory at the Bernabeu was not enough to salvage the tie, and in the post-match press conference, Mourinho hinted that he was returning to Chelsea. “I’m loved by some clubs, especially one,” he said. “In Spain, it’s different. Some people hate me.”

Managing Real Madrid was an emotionally draining experience for Mourinho. Aside from a very brief spell at Benfica in his early days, this was the first time he had failed in his main objective. He hadn’t won La Decima. No longer did he guarantee success. “It’s difficult to be manager of Real Madrid, and it was a turning point in his career,” says Prada. “Since then, he hasn’t had the success he had before.”

A year after Mourinho’s departure, Madrid sealed La Decima and Carlo Ancelotti joined the list of managers to lift the European Cup with a second club – just as Jupp Heynckes had done a year earlier. “When Madrid won it, I was happy,” Mourinho said later, trying very hard to hide the melancholy in his voice.

CHELSEA vs ATLETICO MADRID 2014

“Eden isn’t so ready to lay down his life for the team; if you see Atletico’s first goal, you understand where the mistake was”

The match had reached the 44th minute at Stamford Bridge, and Mourinho was on course for his maiden Champions League final as Chelsea manager. In his first season back at the club, the Blues led Atletico Madrid 1-0, after a goalless draw at the Vicente Calderon in the semi-final’s first leg. All was going to plan.

Then, Atletico midfielder Tiago – whom Mourinho had brought to Chelsea a decade earlier – flighted a pass towards the far post. Eden Hazard, perhaps expecting the ball to soar out of play, let Juanfran run in behind him. The full-back squared for Adrian to fire past Mark Schwarzer, and suddenly Atletico had a crucial away goal. Forced to chase the game, Chelsea eventually lost 3-1.

Months earlier, Mourinho’s first Champions League game back at Chelsea hadn’t gone well, either, as Mohamed Salah helped Basel beat the Blues at the Bridge. Mourinho immediately snapped up the Egyptian, but never got the best out of him.

Midfielder Ramires featured more regularly, and remembers his manager’s determination to progress in the Champions League.

“Once, we had an away match in the group stage and, if we lost, we would have exited the Champions League and dropped into the Europa League,” the Brazilian recalls to FFT. “A day before the game, he got all of the squad together and said, ‘I don’t want to play in the Europa League – if you want to, you will have to play by yourselves, because I don’t want it.’ That had a great impact on the players: we won convincingly and went through to the next phase.

“He always wanted to win the Champions League with Chelsea. If he had to argue, he would argue. If he had to praise someone, he’d praise them. There were games when the team didn’t play well and only one player stood out – he would greet only that player in the dressing room after the match, and leave. He wouldn’t say anything else; only the following day would he criticise us very badly. It was done so that players wouldn’t relax – it was to keep us on our toes. As a coach, he knows so much about football. Training sessions were daily classes of football. I’m happy to say that I worked with him.”

Chelsea were favourites to beat Atletico and it seemed the perfect chance for their manager to claim a third Champions League crown – only for Mourinho to become embroiled in not one but two rows. First, there was the eligibility of Thibaut Courtois, on loan at Atletico from Chelsea. Eventually, UEFA stepped in and said the goalkeeper was allowed to play. Then there was a dispute over the scheduling of a Premier League match at Anfield three days before the second leg. Mourinho fielded a weakened team but Chelsea still won 2-0, thwarting Liverpool’s title bid via Steven Gerrard’s slip.

The game Mourinho really wanted to win went less well. “We were optimistic after our 0-0 draw in the first leg,” remembers Ramires. “I don’t know how to explain what happened in the second game.” Mourinho did. He blamed Hazard for switching off at the crucial moment. “Eden is the kind of player who is not so mentally ready to look back at his left-back and lay down his life for him,” the coach said afterwards. “If you see Atletico’s first goal, you will understand where the mistake was.”

Although Chelsea won the Premier League the following season, they exited the Champions League in lacklustre fashion, losing on away goals to PSG in the last 16. When times got tough at the start of Mourinho’s third season, the public criticism of Hazard returned.

“That had a big impact because he started to lose control of the squad,” admits Ramires. “It’s one thing to say something internally, but it’s totally different to criticise someone publicly. Hazard was our main player, and what he did affected Eden’s game. Hazard used to collect the ball and attack the opposition. He started to pass the ball much more, and we missed our main attacking threat.

“The atmosphere became really heavy. There were guys who were already angry because they weren’t playing. When something like that happened with Hazard, those who weren’t playing had another ally against the manager. It became a snowball that only got bigger. It reached a stage where nothing would improve.”

Mourinho was soon out of a job. He left his post with the reigning Premier League champions sat one point above the relegation zone, having lost nine of their 16 games. Across his two spells at Chelsea, either side of the club’s Champions League triumph in 2012, he had been unable to take them to European glory.

MANCHESTER UNITED vs SEVILLA 2018

“The fans have the right to their opinions, but there’s something that I call football heritage”

Mourinho sat down for his press conference at Manchester United’s Carrington training base, ready to let rip.

In front of him lay a sheet of facts he’d prepared for the occasion, à la Rafa Benitez. Three days earlier, United had lost to Sevilla in the last 16 of the Champions League, sparking criticism from media and supporters. Mourinho decided to respond.

“The last time Manchester United reached the final was in 2011,” he said. “In 2012: out in the group phase. In 2013: out in the last 16 – I was on the other bench,” he added, referencing his victory over United with Real Madrid. “In 2014: out in the quarter-finals. In 2015: no European football. In 2016: out in the group stage. Over seven years, with four different managers, the best was one quarter-final. This is football heritage.”

Every word was said loudly and defiantly. Just as with Chelsea’s semi-final against Barcelona in 2005, Mourinho wanted to set the agenda. This time, it wasn’t such a good idea.

“It was a performance in itself, like going to watch Laurence Olivier at the theatre,” says Samuel Luckhurst, who was in attendance for the Manchester Evening News. “But it didn’t go down well with fans. When a United boss starts antagonising the supporters, you know they’re coming to the end of the road.”

Manchester United returned to the Premier League’s top two that season, for the first time since Alex Ferguson’s retirement in 2013. Mourinho described it, not without calculation, as one of his finest achievements in management. However, the Sevilla showdown was a telltale sign of underlying problems.

With United big favourites to reach the quarter-finals, Mourinho surprisingly started with midfield ace Paul Pogba on the bench for the opening leg in Seville. United fans expected their team to attack inferior opponents, but Mourinho settled for a 0-0 draw.

“His tactics were too small-time,” Luckhurst recalls of that first leg. “Pogba had been unwell going into it, but it was still a bombshell when Scott McTominay was selected ahead of him, and I suspect it wasn’t entirely fitness-related. The Sevilla matches coincided with Mourinho and Pogba being at loggerheads, big-time.

“Pogba didn’t start the second leg either, and United just didn’t turn up – they were rigid, immobile. It was one of the club’s worst post-Ferguson performances. There were so many things going on in the background, and you wonder whether that all took its toll.”

Exactly as it had for Chelsea against Atletico Madrid, a 0-0 draw on the road had left the Red Devils vulnerable to an away goal. Wissam Ben Yedder scored, then scored again. Sevilla triumphed 2-1.

Mourinho’s relationship had deteriorated not just with Pogba but with Anthony Martial, another fan favourite. The increasing age gap made it harder for Mourinho, in his mid-50s, to be the elder brother Desmond Morris discussed. Maybe Ferguson’s fatherly managerial style was always destined to succeed for longer.

“It’s probably why Jose reunited with Zlatan Ibrahimovic, having managed him at Inter – because that was a manageable age gap,” suggests Luckhurst. “Guys like Lampard, Terry and Drogba were all born in a different era, as were his players at Inter. Now managers have to manage millennials, and that’s a different kettle of fish. But some simply refuse to change. At United, Mourinho wasn’t going to bend over backwards to accommodate any players that he felt were undermining him.”

Where once Mourinho’s centre-back signings were astute – Ricardo Carvalho at Chelsea, Lucio at Inter, Raphael Varane at Real Madrid – Eric Bailly and Victor Lindelof didn’t have the desired impact. Eager to recruit another, be it Kalidou Koulibaly, Toby Alderweireld, Milan Skriniar or Harry Maguire, he grew frustrated when the club couldn’t or wouldn’t make a deal happen in the summer of 2018.

By the time Manchester United returned to the knockout stages of the Champions League, to take on PSG, the team were struggling domestically. Mourinho was gone.

TOTTENHAM vs RB LEIPZIG 2020

“When a coach arrives in the middle of the season, it’s because the team has problems”

It’s an overcast winter’s afternoon in Enfield as FFT make our way inside Spurs’ plush training ground, past the autograph hunters and a woman wearing a Son Heung-min face mask.

Today, it’s Mourinho’s weekly press conference. Two days earlier, his Spurs side had lost 1-0 at Southampton, home fans taunting him with chants of ‘You’re not special any more’ and ‘You’re just a s**t Pochettino’. He’d been shown a yellow card for arguing with Saints goalkeeping coach Andrew Sparkes, and responded in typical Jose fashion: “I was rude, but I was rude to an idiot.”

It was a sign that the combative Mourinho still lurks underneath, despite arriving at Spurs in November as the Humble One, conscious of the perception that his antagonistic time with Manchester United had created. Spurs’ squad could have been forgiven for being wary about which Jose they were going to get. The Portuguese was very careful, too, perhaps; a man who’s had huge success as an impact manager, now concerned about making such a great impact that he upsets everyone from the start.

He has been the Humiliated One, too, tumbling embarrassingly in front of the TV cameras on a visit to Wembley, then as he took to the ice for the ceremonial start of a Russian ice hockey match. It’s hard to imagine those moments ever happening to the unstoppable Jose of his early career.

Had the past decade gone perfectly, Mourinho might never have taken the Spurs job. He had turned them down when Martin Jol and then Harry Redknapp moved on; now, he was in charge of a team that was 11 points off the Premier League’s top four when Mauricio Pochettino departed. The road to success may be long – something the 57-year-old was keen to point out as he arrived for his weekly press meeting, complete with bright purple gilet, contrasting starkly with his ever whiter hair.

Before the defeat at Southampton, only Liverpool had collected more points than Tottenham in Mourinho’s first weeks. In the wake of that loss, he was, as always, keen to set the agenda. “Yesterday I watched Liverpool, the best team in the world at this moment, and I Googled it, just to confirm,” he explained. “Jurgen Klopp arrived in October 2015. Eight transfer windows; lots of players leaving; lots of players coming; time to introduce his philosophy; and beautiful results as a result of fantastic work, step by step.

“In the first season, they finished 8th. So we have to remain calm. When a coach comes in the middle of the season, it’s because the team has some problems.”

It’s the first time that Mourinho has taken over a new club midway through a season since Porto in 2002. Back then, he won four games on the bounce, then just two of his next nine matches – similar to the sticky spell that Spurs have experienced recently.

“I see some similarities between Tottenham and our Porto team, especially when it comes to preparing a talented squad to reach the next level,” explains Vitor Baia. “They should be patient, and success will eventually come to them under Mourinho. He doesn’t need to prove his qualities.

“Tottenham have a lot of tradition, but Mourinho has this power of attracting a lot of attention, which will enable them to sell their brand in the Asian and Middle East markets. The club will get more money and become even more famous with Mourinho. That’s part of the process to win big trophies. It happened to Porto, and it will probably happen to Tottenham.”

Porto were Portuguese champions within 18 months – although such is the high standard at the top of English football, it would be a huge ask for Spurs to win the Premier League in 2020-21.

“This isn’t going to be the typical Mourinho, where he bursts onto the scene, wins the Premier League twice, then leaves,” says Glen Johnson, thinking back to their time at Chelsea. “He will have to give Tottenham a good five years. But he’s never done it before.”

As for the Champions League, Mourinho guided the Londoners to the last 16 with a comeback victory over Olympiakos in November, but they take on RB Leipzig without injured talisman Harry Kane.

Although they are facing an uphill struggle to qualify for the next edition, Carlos Alberto believes it is possible for Mourinho to win the Champions League with Spurs at some point. “Let’s not forget that Tottenham are the current runners-up,” says the ex-Porto striker. “They’re not the biggest favourites to win it this season, but they’ve already proved their strength. So, yes, there’s potential to win it, and Mourinho is keen to show the world he can do it again.”

Specifically, Jose is keen to show that, after 10 years without any Champions League glory, those days aren’t behind him.

“It isn’t easy to win the Champions League,” says Baia, dismissing his former manager’s decade-long drought. “Pep Guardiola couldn’t win it with Bayern Munich and Manchester City. PSG threw money at it and haven’t won it. Mourinho won it for two different clubs and that’s already impressive. For me, he’s the greatest manager ever.”

If he does win it with a third club one day, no one will be able to dispute that view, according to Carlos Alberto. “That’s more difficult than it is to win three times with the same club,” he insists. “It’s so difficult to win the Champions League even once – imagine doing it for three different clubs.”

Mourinho has imagined it for 10 long years. “Do I want to win it for a third time? Of course,” he said before his first European game with Spurs. El Dorado is still on his mind. The quest to return to that magical place has come close to destroying him, just as it destroyed Sir Walter Raleigh. Not finding the city of gold on his first expedition, he tried for a second time 22 years later. Ignoring a ceasefire in the Anglo-Spanish War, his men attacked a Spanish outpost on the Orinoco, and his son was killed.

Raleigh never did find El Dorado. When he returned to England, he was sentenced to death for violating the ceasefire. For his bosses, it had been one battle too many.

Thankfully, the consequences of failure won’t be quite that dire for Jose Mourinho. But if he’s ever to reach El Dorado again, there aren’t many more battles he can afford to lose.

While you’re here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers’ offer? Get the game’s greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £12.25 every three months – less than £3.80 per issue – and you’ll also receive bookazines worth £29.97!

NOW READ...

INTERNATIONAL UEFA Nations League explained: Everything you need to know about the new format

QUIZ Can you name every club Marcus Rashford has scored against?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Chris joined FourFourTwo in 2015 and has reported from 20 countries, in places as varied as Jerusalem and the Arctic Circle. He's interviewed Pele, Zlatan and Santa Claus (it's a long story), as well as covering the World Cup, Euro 2020 and the Clasico. He previously spent 10 years as a newspaper journalist, and completed the 92 in 2017.