Kicking it old school: how the traditional winger is coming back into fashion

English football has lost many things, writes Alex Hess, but it's rediscovered its love for the touchline-hugging wideman – even if they are now in modern guises...

The cheapening of the FA Cup; the ever-more disposable status of the manager; the whittling away of 3pm kick-offs. It’s easy to look at British football and see only a collection of sacred cornerstones being eroded by the tide of the modern era. But those bemoaning our national sport’s one-way trip to hell in a handcart needn’t despair just yet. They can take heart from the fact that, on the pitch, we’re currently seeing the emphatic re-emergence of one of its grandest traditions. From Bastin to Beckham via Best and Barnes, England’s leagues have never been short of gallivanting widemen. Well, almost never. More recently it’s seemed as though the role made iconic by Stanley Matthews and Tom Finney was another footballing institution destined for the scrapheap. But if the opening weeks of this season have shown one thing, it’s that bewitching wingplay is a weapon that remains unblunted by the passage of time.

Bringing it back

Of the campaign’s nascent stages, Riyad Mahrez’s elusive slithers down Leicester City’s right flank have been a particular highlight, as have the now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t tricks with which Swansea’s Jefferson Montero has been tormenting full-backs at will.

If the opening weeks of this season have shown one thing, it’s that bewitching wingplay is a weapon that remains unblunted by the passage of time

Elsewhere, Manchester City have assumed the role of early title favourites with a pair of flankers doing much to prove their doubters wrong. On the right, Jesus Navas – often dismissed as a glorified Jermaine Pennant during his first two years in England – has added some welcome end product to his foraging runs; on the other side, the incisive, intelligent displays from Raheem Sterling have offered one in the eye for the many who spent the summer scoffing at his price tag.

Across town, Memphis Depay’s forays from the left have been some of the only times when the Theatre of Dreams has been roused from its slumber. And down in the capital, Crystal Palace’s bubble shows no sign of bursting yet – the south Londoners are among the league’s most exciting sides, thanks chiefly to the jinking quadrant of Bakary Sako, Yannick Bolasie, Jason Puncheon and Wilfried Zaha.

Largely playing on the 'wrong' flank – as popularised by Ronaldinho and Lionel Messi only a decade ago – and concluding their dribbles with a shot as often as a cross, it might seem a stretch to call these men a throwback. But within a shrunken timeframe, they are exactly that.

One of the more notable tactical trends in recent years has been the re-deployment of widemen to the middle. The classically trained No.10 – the playmaking stroller, shirt untucked and socks rolled down – has found himself threatened with extinction by the mass relocation of the zippy dribbler.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

DOWNLOAD STATS ZONE FOR FREE NOW iOS • Android

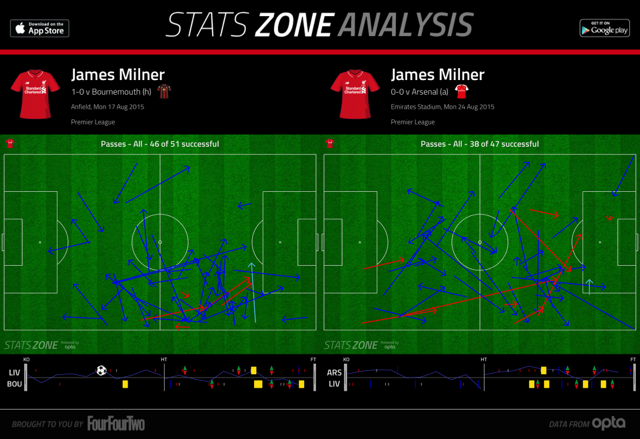

Some such reshuffles have proved canny moves. Last season, Stewart Downing’s reinvention from one-paced winger to roving central creator was one of Sam Allardyce’s few deeds to be received kindly by the Upton Park faithful, while Nacer Chadli’s move to a support striker’s role put him in the minority of Spurs’ post-Bale signings to have borne any fruit. This term, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain’s development looks to be accelerating in the engine room and James Milner has made a splendid start to his Liverpool career.

Wing wins

A similar idea lay behind another of Liverpool’s big-name British signings of the recent past, though Joe Cole's story is more cautionary than fairytale. A fiendish central midfielder in his West Ham days, Cole grew frustrated at his inability to shed the ‘diligent winger’ label pinned to his back by one Jose Mourinho. Yet Cole’s visions of dictating games at Anfield were undermined by form, fitness and suitability.

You wonder if his side would have fared better with one or two players in the style of Marc Overmars or Robert Pires

Perhaps his error was to misinterpret deployment on the margins for marginalisation – his most rampant form, after all, always came as a flying flanker. Cole’s swashbuckling performance as Chelsea ravaged the Barcelona of Ronaldinho and Rijkaard 4-2 in 2005 was perhaps the pinnacle of his club career, while his much-replayed volley against Sweden in the World Cup the following summer also came from the wing. Sometimes Jose knows best.

It is because of Mourinho that Eden Hazard still gets the odd spot of chalk on his boots. Last season’s player of the year has made little secret of the fact that he sees his best position to be the free-roaming central role he enjoyed at Lille. He may be right, he may not. But as a player whose foremost traits are explosive speed and fearless, adhesive dribbling – and, more simply, as a player who continues to excel on the wing – you wonder quite what he has against his current stationing. At Arsenal, Arsene Wenger seems to have used the past half-decade to do away with wingers altogether and instead embark on a one-man mission to crowbar in as many central playmakers as one teamsheet will allow. The club’s trophy cabinet has grown notably dusty during this venture and you wonder if his side would have fared better with one or two players in the style of Marc Overmars or Robert Pires rather than a 10 like Andres Iniesta.

Bale-out plan

Gary Neville suggests that the career trajectory of Cristiano Ronaldo had “conned” a generation of wingers into believing that they should be playing in the centre

Speaking on Sky Sports on Monday, Gary Neville suggested that the career trajectory of Cristiano Ronaldo had “conned” a generation of wingers into believing that they should be playing in the centre. If so, it’s a desperately misplaced notion. From around 2007 onwards, Ronaldo transformed his physique and skill set to the point where both are barely recognisable from his earlier self; his switch in position followed accordingly. It is no exaggeration to say that the Ronaldo of today, a powerhouse centre-forward, has more in common with the late-1990s Alan Shearer than he does with the spindly winger who joined United in 2003. So for someone like Erik Lamela, for instance, to cast a quick glance at the Portuguese and covet a central role for himself simply makes no sense.

Neville didn’t mention Messi but the Argentine’s move from inverted winger to roving middle man has surely been another driving force behind the faddish forsaking of wingplay. But again, Messi’s freakish all-round brilliance can’t be replicated with a tactics board. Simply moving a winger to the No.10 role won’t turn him into little Leo – and nor will it make its instigator Pep Guardiola.

Perhaps the strangest and most needless example of the phenomenon is happening right now at Real Madrid, where it's reported that one of Rafa Benitez’s key remits as head coach/payoff-recipient-in-waiting is to get Gareth Bale flourishing in a central role. Quite why a club which already counts Isco, Toni Kroos and Mateo Kovacic among its employees would feel the urge to assign playmaking duties to its most natural winger is a question only the boardroom brains may be able to answer. Certainly, Bale's fruitless display there during Saturday's 0-0 draw at Sporting Gijon hinted at more than a little naivety behind the idea. The Welshman has always been more cannonball than craftsman, a player at his best when guzzling up expanses of turf – of which there is plenty on the wing, much less in the pitch's congested centre. It’s a bizarre endeavour at best. All of which has made the recent sight of England’s wingers tearing at their full-back with gay abandon all the more pleasing. The flanker scooting along at full speed, feinting feet a blur, is one of football’s most thrillingly visceral sights; occupying the Venn diagram overlap of feathery technique and fiery athleticism. And if there’s a silver lining to take from the recent shortage of widemen, it’s that the spectacle they provide is like all great joys: best appreciated after a while without a fix.