When Leeds United did pantomime: Jimmy Armfield's grand 1975 plan to revive the Whites

When Jimmy Armfield took over an ailing Leeds side, only one thing could get them back on track: a show for the locals

The disciplinary panel didn’t see the first punch. Neither did Francis Lee. A thudding right hook delivered by Leeds United’s Norman Hunter, it knocked the Derby County forward to his knees, splitting his lip so badly that he could poke his tongue through the gash.

Lee, who had enraged the opposition by tumbling over a barely outstretched leg to win a penalty and make it 2-1 in this fierce First Division battle a few days before Bonfire Night in 1975, clambered to his feet, ready to fight back. Team-mate Charlie George, together with David Harvey and Trevor Cherry, got in his way as Billy Bremner tried to stop Derby’s Kevin Hector’s unwise lunge towards Hunter. Referee Derek Nippard stepped in and sent the combatants off. Which meant that, when they met at Lancaster Gate three weeks later, stitches out and bruises healed, the FA could only deal with what happened next.

Since the film the panel watched was silent, they missed out on the increasingly frenetic Match of the Day commentary, too. “A fight’s going on off the ball between Hunter and Lee,” began John Motson. “Fists were flying and that’s been brewing for some time... I’m wondering if he’s sent them off, because they’re wandering away to the far side. And it looks to me as if it’s broken out again! It’s broken out again, and this time, a complete free-for-all. And I’m sure they must have been sent off this time. And the referee’s trying to sort it all out. If they weren’t sent off the first time, they certainly were the second.”

The panel only saw the ‘afters’: Lee swinging wildly, knocking Hunter to the ground with the last of four blows before team-mates, coaches and managers jump in – in a couple of cases, literally – to restore order.

So while Lee received a four-match ban and a £250 fine for disrepute (“It’s the worst thing that’s happened to me in 10 years of league football,” he said), Hunter came away smiling. Dressed in suit and tie, he climbed into a car with manager Jimmy Armfield and headed back to Leeds to take part in that night’s fixture.

Oh yes he is

A few hours later, the archetypal hard man emerged from the dressing room to a familiar roar and gazed out at his public. Not tonight, though, the faithful of the Lowfields and the Scratching Shed at Elland Road. Instead, Hunter looked out on an audience of mums and dads and lads and lasses at the City Varieties Music Hall, all gathered to watch Leeds United – that wonderful, cynical, glamorous, brutal, thrilling 1970s force – stage a pantomime.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“Here’s Baron Diver, back from London,” declared Armfield, clad in velvet, as Hunter walked towards the front of the stage and delivered a passable version of the nation’s current favourite catchphrase. In a northern approximation of Bruce Forsyth’s voice, and with a wink, he asked the audience: “Didn’t we do well?”

If any team of the time were going to savour the smell of the greasepaint and the roar of the crowd, it had to be Leeds.

With The Beatles having split, the England team in disgrace and Manchester United recently exiled to the Second Division, this was arguably the most famous collective of individuals in Britain.

They had international stars like Billy Bremner, Terry Yorath, Johnny Giles and Eddie Gray. They had players with nicknames – ‘Bite Yer Legs’ Hunter, ‘Sniffer’ Clarke, ‘Hot-Shot’ Lorimer. They wore numbered sock tags and had recently replaced their staid peacock motif with the famous ‘smiley badge’.

They had even recorded a top 10 single, Glory Glory Leeds United, featuring the memorable verse: “Little Billy Bremner is the captain of the crew/For the sake of Leeds United he would tear himself in two/His hair is red and fuzzy but his body’s black and blue.”

Says journalist John Wray, then covering the club for the Bradford Telegraph & Argus: “They were the best team in the country, they were the most talked-about team in the country and they were the most fashionable team in the country. When you covered them, you felt like the whole world was looking in. It felt like you were at the centre of something exceptional.”

Forty-four days

Yet by October 1974 the only thing exceptional about Leeds United was the speed with which they had lately fallen from grace. With Revie gone to replace Sir Alf Ramsey as England manager following Hunter’s disastrous gaffe against Poland in the final World Cup qualifier, Leeds had recruited Brighton’s Brian Clough as The Don’s replacement, against his wishes.

The next 44 days, which were memorably re-imagined by writer David Peace in his remarkable novel The Damned United, were stranger than fiction. Players were told to hand in the medals accumulated under Revie as they’d been won by cheating. New signings John McGovern and John O’Hare were shunned because Clough had managed them at Derby. Another new capture, Nottingham Forest’s Duncan McKenzie, was derided as surplus to requirements in a team bursting with attacking threat.

When Bremner and Kevin Keegan were dismissed for swapping punches in the Charity Shield, United fell into national disgrace. After the season began, the league champions slumped into the drop zone and stayed there until a players’ deputation to the boardroom forced the interloper out.

Into this poisonous atmosphere arrived Jimmy Armfield. Once captain of Blackpool and England, he had prepared for a second career in journalism before taking up an offer to manage Bolton, where he met with modest success. Then again, much about the avuncular Armfield was modest. “He was almost too nice to be a manager,” says McKenzie. “Jimmy was like the nice neighbour that everyone wants next door.”

Yet this neighbour had 61 England caps’ worth of cunning. “I needed to get rid of the sour feeling, the sour taste,” Armfield says. “I wanted to get the team back on its feet and I thought we needed a bonding exercise. So I phoned Barney Colehan and said, ‘I’ve got this idea...’”

Armed with a plan

A theatre, radio and TV impresario from the Leeds suburb of Calverley, Colehan took charge of two long-running shows on the small screen. The first was It’s A Knockout, and he had produced a special 1972 FA Cup Final version before Leeds’s Wembley victory against Arsenal. The second was The Good Old Days, Victorian-era entertainment for a costumed crowd under the alliterative chairmanship of Leonard Sachs.

“I told Barney about this thought I’d had about the players doing a pantomime,” says Armfield. “I thought we could put it on at Elland Road on a lunchtime. He said: ‘Great, we’ll do it at the City Varieties, like The Good Old Days. I’ll go off and organise the costumes, let’s put it on for a week.’ I thought: 'Flippin’ heck'.”

Now all that was left was to inform the players who had recently turned on Clough that they would have to spend more time in training. Not to work on set-pieces, but to rehearse for a theatrical production in which many of them would appear in drag. “They all looked at me,” recalls Armfield, “like I had gone mad.”

All except one. “When he told us about the panto for the first time I thought ‘that’s quite clever’,” says Duncan McKenzie. “I could understand what he was trying to achieve. Jimmy was wily. I remember Norman Hunter coming in once after finding out he’d been dropped and he was absolutely fuming.

"He stormed right into Jimmy’s office and Jimmy was sitting there with a cup of tea. He said: ‘Good morning Norman, how’s the wife and kids?’ They had a chat about all of that and after 10 minutes I’m not sure Norman could remember why he’d gone in there in the first place.”

On this occasion, though, Hunter offered stiffer resistance. “I thought it was stupid,” he says. “I was probably the most reluctant to start with. I thought: ‘Who’s going to come to watch that?’”

But Armfield had an ace up his sleeve. “I told them that half the proceeds would go to charity and half to a testimonial fund,” he explains. “That first year, it was Norman’s testimonial. They could hardly say no after that.”

Persuasive powers

With results improving on the pitch, Armfield’s wary players began to settle into the idea. “There were a few jokes about a pantomime off the pitch and a pantomime on it, but they really got down to it,” says the manager. “We just chucked ourselves into it,” says Hunter. “We might have needed to bond with Jimmy, but we didn’t need to bond as a team. It did bring us closer together with Duncan, but you couldn’t help that anyway. The fella’s infectious. Duncan could never be an outsider anywhere.”

Explains John Wray: “It definitely helped team spirit. Duncan was on a hiding to nothing because Cloughie had brought him in and the players had already not taken to McGovern and O’Hare – according to those lads, the old guard wouldn’t even pass to them. Duncan’s personality could win over anyone and the panto helped him do it.”

Any remaining doubts were settled by the arrival of Armfield’s script, titled Cinderella. “There was a lot of laughter at the first rehearsal,” he recalls. “I’d written a lot of corny jokes, but they were jokes that related to the players. They loved it. We had a read-through, I gave them each a copy and they got on with it.”

Says McKenzie: “When we got the script we were relieved because you could see it would work. Jimmy knew you couldn’t give footballers lines of dialogue to say to each other. So he was going to play the narrator, and he stood behind a lectern at the side of the stage. I played the title role, and at the start I was supposed to walk out in my Cinderella gear and Jimmy would say: ‘Here comes Cinders, straight from the Forest.’ It wouldn’t win you any awards, but it ended up getting a big laugh.”

“The funniest bit,” says Armfield, “was Terry Yorath’s singing. He had to sing ‘Climb up on my knee, sonny boy’ to Billy. We quickly realised we’d found the only Welshman who couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket.”

Got yer tickets

Hunter had wondered whether anyone would want to turn up to see their efforts. As tickets went on sale, he had his answer. “Because of the fixtures, we could only do two days,” says Armfield. “We sold out in the space of an hour. Barney reckoned we could have played to a full house every night for a month.” Come December 1974’s opening night, the City Varieties – where Charlie Chaplin, Harry Houdini and music hall queen Marie Lloyd had all drawn full houses – was packed to the rafters. “They were sitting in the side aisles, standing up at the back,” recalls McKenzie. “You couldn’t do it now, with health and safety.”

“Behind the curtain,” says Hunter, “there was a lot of trepidation. Jimmy lined us up for a team talk.”

The players got the benefit of their manager’s wisdom, and a little extra. “Billy was there in his little cap and tails, the Good Fairy McQueen was there in her tutu,” says Armfield. “I told them that the greatest managers in the world had never given a talk like this to players who looked like they did. Then I said: 'Does anyone need a drink?’ I’d read that some theatre people needed a drink to go on. It was brandy, I think, and a few of them had a nip for nerves. I was one of the few who had a nip.”

Then the curtains opened and, to a roar, out came McKenzie. “Duncan was known for two party tricks in those days,” says John Wray. “He could throw a golf ball the full length of a football pitch and if he had a run-up he could jump over a Mini. On the first night, he came on with a fag held between his nose and his top lip. He was able to do the spectacular with ordinary things and the kids lapped it up.”

Adds Armfield: “Later on Duncan pulled up his dress. He had stockings on and he had some fags stuck in his stocking tops. He took one out and lit up. The crowd loved that.”

The players’ worries were quickly assuaged. “I had to say ‘whoever’s foot this slipper fits will be my Queen’,” remembers Hunter. “I might have got it wrong in rehearsal. But on the night your professionalism came out. Nobody wanted to make the first mistake. We were word perfect, almost. It was the excitement. And I’m not like that myself, but I got the feeling that some of the lads quite enjoyed the dressing up.”

Says John Wray: “I’d gone with a sinking feeling, but the first thing you thought was ‘this isn’t completely amateurish’. The second was ‘this is actually pretty slick’. It was extremely well done and obviously the players were thoroughly enjoying it.”

Billy Buttons

The night was already a hit when the club captain made one of his famous solo forays into uncharted territory. “Cinders asked ‘Where’s Buttons?’ said Armfield. “And Billy came skipping down the centre aisle, with his brass buttons and his pill box hat, throwing out sweets to the kids. He was a natural, Billy. He should have been on the stage.”

Wray says: “Billy was a terrific guy and he was a man of the people. He’d come from a very poor family in Scotland, desperately poor. He actually had a very unpretentious house in Temple Newsham; you wouldn’t believe that the captain of Leeds United and Scotland, the David Beckham of his day, lived there. He got on famously with all his neighbours. Later on he moved to Doncaster and he’d go out drinking with the mining community. So to the people who knew what he was really like, it wasn’t a surprise to see him like that.

“He smoked like a mill chimney, though. If you sat next to him on the team coach, you’d end up reeking of smoke, and he had these yellow fingers from the fags. So it was quite a sight that night – the costume, the red hair, the chalky white skin, the yellow fingers, handing out the sweets.”

Adds Hunter: “I was looking in the attic the other day and I found one of the pictures of little Billy. You couldn’t have had a better Buttons than him. He loved kids and he loved the people.”

The people, in turn, loved the panto. “The script ran for about an hour,” says Armfield. “But with all the cheers and the clapping, it went on for 90 minutes, like a match. It took a long time to calm it all down. The curtain calls seemed to go on forever.”

Panto to pitch

Some in the press had worried that the panto would be an unwelcome distraction. “But we didn’t do too bad, did we?” asks Armfield. Leeds finished the season just eight points behind champions Derby, and beat Barcelona to reach the European Cup final against Bayern Munich.

But there were to be no standing ovations, no glorious curtain calls, at the Parc des Princes. United dominated the match, had a Lorimer goal disallowed after Bremner had strayed offside, then were hit by two sucker punches. Fans ripped their seats out and hurled them onto the pitch, resulting in a two-year UEFA ban for the team. Most of United’s great veterans would never play in Europe again.

RECOMMENDED Robbery, rioting and a brave Frenchman: Leeds' 1975 European Cup Final retold

Six months after that dreadful May night, Armfield staged the panto again. “I would have loved to have kept on doing them every year, but I had to start breaking up the team and it would have got a bit difficult.” So future Armfield signings like Tony Currie and Brian Flynn were denied their right to tread the boards.

Says Hunter: “The old guard started to disappear. I went to Bristol City, Billy went to Hull, Gilesy went to West Brom. It was the end of an era and we didn’t feel bitter towards Jimmy for that, even though I think a few of us could have carried on a bit longer.”

McKenzie went too, to Anderlecht, leaving Elland Road with a profound sense of what one man and a few nights in December had done for club. “I think Jimmy knew from the start that one of his jobs was to continue the job that Cloughie had started and to break up that great team,” he said. “But with things like the panto, he was able to do it in a nice way, a gentlemanly way. Not shock tactics like Cloughie.

“Brian told them that they’d won their medals by cheating. But Jimmy helped them realise that they had won some things not because of Don Revie, but in spite of Don Revie. They’d never really been told to just go out and play before. And I think that it gradually began to dawn that they should and could have won far more than they did. We felt very close together.

“You were a lot closer to the fans than players are today. You earned a lot more than they did, but nothing like the money now. Your ultimate ambition was to retire with a nice house and no mortgage. You did your bit. You presented prizes at the school, you had a drink in the local. So doing the panto almost felt natural.

“Now, when I do matchday stuff, the away team arrive and they put a shield in front of the bus. You can’t get an autograph. The kids can’t even see the players. It's a different world that we’ve created, and I don’t think it’s a better one.”

This feature originally appeared in the January 2009 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get the game's greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £9.50 every quarter – just £2.90 an issue. Cheers!

NOW READ...

GUIDE How to watch Amazon Prime Premier League fixtures on Boxing Day for FREE

LIST 10 of English football's craziest Christmas matches

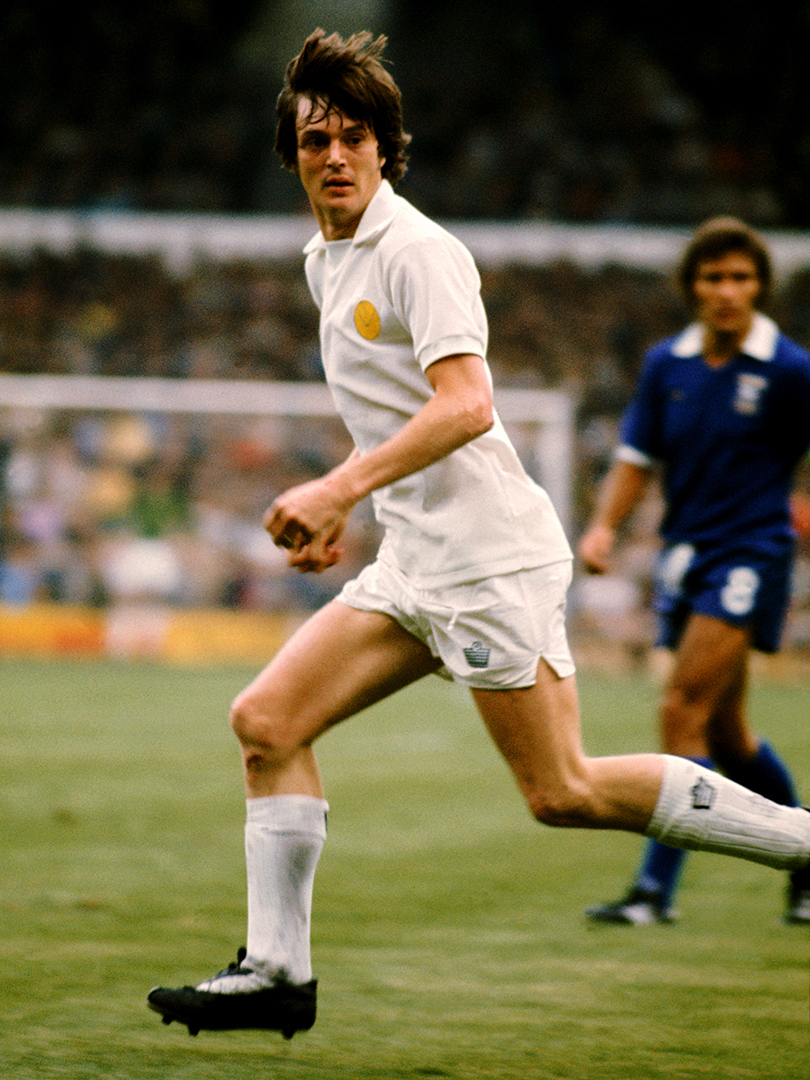

ACTION REPLAY The Leeds United pantomime: Bremner as Buttons, Hunter as Prince Charming...