Liverpool legend recalls the day he killed a man – and why

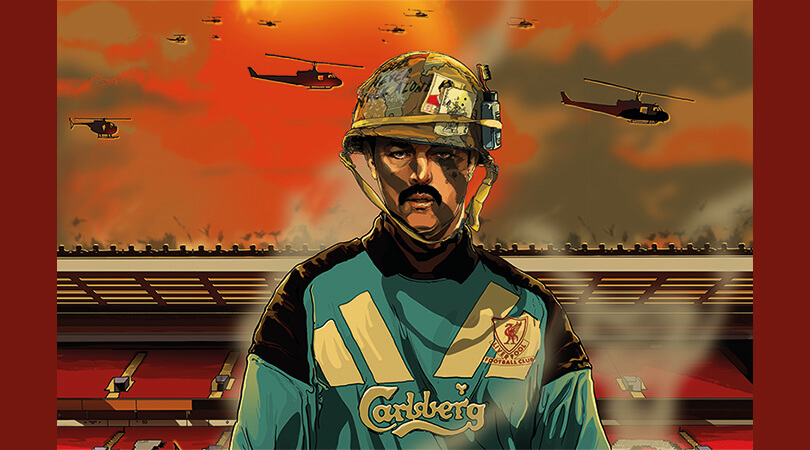

Bruce Grobbelaar won the lot with Liverpool, but only after fighting in the Rhodesian Bush War as a teenager. He shares his remarkable story – and how the harrowing experience helped him to stand up to King Kenny

It’s you or them. You’re crouched, tracking the enemy through the bush. It’s dusk. You’re surrounded by acacia trees, the low sun is streaming through the long grass – and then you see them. A pair of eyes staring right into yours. You have to act first.

To survive, you have to act first.

It’s you or them. You’re a young footballer, arriving from a faraway country. Your new place of work is with the multiple European Cup winners, and you’re among some of the best players in the world. There’s a hierarchy. Senior pros want to test a newcomer’s mettle. You have to act first. To survive, you have to act first.

In with the new

I came to Liverpool FC in March 1981. Just weeks later, the club beat Real Madrid in Paris to win the European Cup. But the squad, housing players who had been there so long and won so much, was nearing its end. They were fantastic players, yes, but Bob Paisley and his incredible backroom staff knew that some of their legs had gone.

My first game was a testimonial for Stevie Heighway at Anfield. The likes of Jimmy Case, Ray Kennedy, David Johnson and, of course, Stevie himself were involved, but soon they would all be leaving. Bob was planning to blood a new crop of youngsters. This being Liverpool, players had been bought, put in the reserves and given time to learn – but now was their time.

I didn’t have much time to acclimatise. In the summer of 1981, Ray Clemence – for me, the best goalkeeper anywhere – decided that collecting a third European Cup winner’s medal meant there were no more challenges at Liverpool. Steve Ogrizovic was at the club, too, but Bob decided that I was to get the No.1 jersey. All of a sudden, I was in.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

There was me, Steve Nicol, Craig Johnston, Ronnie Whelan, Ian Rush and Sammy Lee: young, new players, eager to get on but now at the mercy of senior pros, who were just as eager to make jokes and belittle any little thing they could. It was incessant. It never stopped. You’d walk into training and anything could trigger it. New shoes, a new haircut, a new shirt – you’d hear about it. And some struggled.

I could see that some of the lads hated being there. They worried every time they stepped onto the training pitch. We called the worst of them ‘The Scottish Mafia’: Kenny Dalglish, Graeme Souness and Alan Hansen were brilliant footballers, but my god, they could dish out the stick. Rushie and Ronnie both took a lot and it was getting to them. Early on, I said to them both, “Lads, you have to fight back. Give it back to them. Don’t be scared.” They had to, or they would crumble.

War and witch doctors

I had seen men crumble. I had seen it happen, in men sent to war and men who came back from war. Their experiences and what they had seen had proven too much. Men turned to alcohol; they turned to drugs; they turned to suicide. No one talked of stress, nor conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Young men were simply sent to fight and then told to get on with their lives.

I didn’t want to be a soldier. Sport had been my passion from a very young age and I just wanted to play football. As a teenager I’d played for a white team in Rhodesia but moved to a predominantly black team called Matabeleland Highlanders, where the club hero was a witch doctor.

Before games, we’d be taken to a garden. A man would come out of the house all dressed with feathers in his hair, wearing the skin of a leopard over his shoulders, with a skirt of beads and bells that would jangle against his legs.

Us players would take off our clothes and stand there in a circle while the witch doctor held a bucket of water in one hand and the tail of a goat in the other. He would dip the tail in the bucket – at the bottom of it was cow dung and grass – and he’d sprinkle each player with it. Then we’d go and get our kits on, head to the stadium and play. If we won, the witch doctor was the star. If we lost, then you wouldn’t see him and we’d get all of the grief from the supporters.

I fell out with the manager at the next team I played for, and so I decided to move to South Africa, where I could play despite having a contract in Rhodesia. That move didn’t happen, though. My mother, a very strong woman, knew I’d have to do my national service at some point, so she marched me down to the local barracks to see when this would be happening.

“Six months’ time,” the sergeant told us. “In six months’ time I’ll be surfing in Durban,” I said, cockily.

“Actually, there’s a space to come in tomorrow morning,” he replied, wiping the smirk right off my face. At that point, my mum grabbed a pen and signed me up. There and then, I was a soldier.

Rugby will do

My mum’s thought was that it was better to get it over and done with. She was right, and at first I just got on with learning my new trade. For six weeks we trained, but then every weekend for the next six months we had to do our marches, not to mention long, hard runs. It wasn’t my idea of fun. Fortunately, I found a way out.

If I was part of a sports team, I could get away with playing for them instead. It was rugby season, so we cobbled together a rugby team. I was the fly-half and a good kicker, and we actually did pretty well. When that season ended, I started a baseball team for the baseball season. Instead of doing gruelling 75k runs every weekend, I was playing sport and enjoying a couple of beers. We would come back and our fellow soldiers would grumble, “You bastards.”

But that’s where the fun stopped.

By now, the Bush War was raging, and in 1975 I was sent to battle. At first I was conscripted for border controls, and that was all quite relaxed – just checking people who’d come over in their cars, perhaps confiscating some chocolate or cigarettes. Then, one day, we got mortared by the other side and things changed. People around me were injured and it suddenly all felt very real.

Our captain, Captain Taylor, decided that our company should be a mobile unit, which meant that 20 of us had to go for tracking-skills training, 20 for medical training and 20 for signals training. Only 10 of us made it as trackers, and I was among them. Then we went for survival training, being taught how to survive if or when we got captured. We learned from people who had been in the SAS, who were able to teach us how not to give away your regiment and how to cope psychologically with questioning and torture.

And then we were prepared, and dropped into battle. Literally.

SEE ALSO Inside the secret fight against match-fixing in football

This is real

You’re in groups of five. The helicopter flies you to an area where they believe the enemy is operating. You’re being dropped into gunfire, so you’re getting shot at from below as you slowly land.

I’ve seen machine gunners shot in the foot. Often you’re forced to work in groups of three until the guys who have been wounded can be replaced, but you just get on with it. Your job is to locate the enemy and track them through the bush.

I remember the first day that I had to kill someone. It’s not like it is in the movies. As the stick leader – meaning the main tracker – I’m out in front. One day, early on, suddenly there’s the enemy, right in front of me. He’s in camouflage, with his rifle ready and his eyes locked on mine.

My heart is pumping, blood pounding in my ears. I have to act first – and I do. I pull the trigger and I drop, feeling relief that I hit him before he hit me. Suddenly there’s rifle fire everywhere and I’m just hoping it’s not my turn.

Only later do you realise the full effect of what you are doing. Our regiment had to pick up all of the bodies, be they our own or that of the enemy. It was an order, because the army could gain a lot of information from the dead and get an idea of what regiments were where, giving them valuable intel. I found that hard. I would go back and find a body that I’d shot, and I could see first-hand what I’d done to a person. It made me feel sick.

Men handled it in different ways. One guy cut off the ears from each freedom fighter – that’s what the enemy called themselves – he killed and kept each one in a jar. His family had suffered and he wanted brutal revenge. I had no such hate, but I was in a war and I had to get on; I had to become numb to the situation that I found myself in.

Marijuana helped. You kill someone and then later that night, the guys have rolled a few joints and you have a couple of puffs and it helps you to forget. It still triggers something in the brain, though. Years later I was in Cape Town, having a few puffs on a joint, and it did something to me. I thought I was being attacked, and I jumped into a swimming pool. It had triggered a flashback.

In the jungle, you did what you had to do to survive. You ate whatever moved; you bathed in cow shit just to put the enemy off your scent; and you killed. I couldn’t tell you how many men I killed. But, suddenly, one day it’s all over. You’ve done your bit, and you just thank your lucky stars that you made it out of there alive.

It wasn’t over for everyone, though. Some had to do second tours. Many took their own lives when they were told to do another six months. I knew two who killed themselves in the barracks toilets. I was lucky. I had football, and I truly believe that was what saved my life.

Stroke of luck

Having escaped the civil war in Rhodesia, I finally got the chance to play football in South Africa, first with Highlands Park, then with Durban City. But one day I received a letter from the government instructing me to join their army in their battle against what the South African regime deemed communism. As I’d lived and worked in their country for over two years – not to mention the fact that I had a decent amount of military experience – they called me up. But I just couldn’t do all that again. I had to get out, and football was my ticket.

I got a trial at West Bromwich Albion. I loved being there. Ron Atkinson was the manager of an exciting team, with Cyrille Regis and Laurie Cunningham among the players. There was just one small problem: I couldn’t get a working visa.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but the fact that my grandfather had been born during the Boer War in a Cape Town fort – a British stronghold and, by law, British soil – meant I was eligible for a British passport. If I’d known that at the time, I think I may well have stayed at The Hawthorns, and maybe all of those medals I would later win at Liverpool would have been lost. Or maybe West Brom would have won them all instead!

Anyway, just as I thought I was going to have to go back home and ‘get a proper job’, as my mother often said, an opportunity came up to play in Canada for the Vancouver Whitecaps. I got better as a goalkeeper, playing against the likes of Pele, Johan Cruyff, George Best and Franz Beckenbauer, but I wasn’t a regular and it was decided that I should play in England where I could improve further.

I was told I would be playing for the strongest team in England. Then I discovered that my loan move was to Crewe Alexandra. “I thought I was going to the strongest team in England,” I said. “You are,” my manager replied. “Crewe are the strongest. Look at the league tables – they’re propping up everyone else...”

The joke wasn’t fully on me, though, because it was at Crewe that Bob Paisley and his scouts spotted me, and my life changed forever.

RECOMMENDED Serie A in the '90s: when Baggio, Batistuta and Italian football ruled the world

Can’t have it all

Bob was an incredible man, even though he couldn’t pronounce my name – which, to be honest, wasn’t that unusual back then. ‘Grobble-de-jack’, he would call me. I don’t think he said a sentence that I fully understood in the whole time he was my manager, but he had an incredible knowledge of football, and he was able to get that understanding of the game across to his players like no other.

Not that suddenly being a Liverpool player was easy going. They’d spent £250,000 on me, which at the time was a record for a British club buying a goalkeeper. I presumed that, because of this, when I flew into Heathrow from Vancouver I might be met by someone from the club. I wasn’t expecting any fanfare; just for someone from Liverpool to be there waiting for me, to help get me up to Merseyside.

There was no one. I used a payphone and called the club. “Get a flight to Manchester,” came the curt reply, and the line went dead. I had to find my own way from Manchester to Liverpool.

I mean, I’d been dropped into the jungle under machine gun fire, and I had tracked enemy soldiers through thick African bush, so finding my way around England was something I could do. But the frosty welcome seemed a bit strange. I soon realised that was how Liverpool Football Club operated.

Graeme Souness had once asked [then-assistant] Joe Fagan where he wanted him to do his work on the pitch. Joe looked at him and said, “We’ve paid a lot of money for you – you should be able to figure that out yourself.” You were expected to work it all out. You would be tested, and you had to pass.

That’s what the senior pros were doing. When a new player joined up with the first-team squad, the club quickly allocated an old head to show you how to be a Liverpool player. Yes, that meant taking you out for a few drinks, but there was more to it than that. The likes of Kenny were always testing young players with their banter, pushing them to see if they could handle the dressing room. They knew just how important team spirit was to the club’s success and they wanted to see if a new player could handle it. I could.

Hardened

I’d seen too much to let what was happening get to me. I was always a confident young man – my mother and father had made sure of that – and I could immediately handle the mental side of the game. They went for me, though. My accent, my stories about the war and about Africa – none of them believed me, and they tried to ridicule me. But I gave it right back.

“Who are you?” I would say to them. “Who made you manager?” They respected that. Soon, the likes of Rushie and Ronnie were giving it back, too.

The thing is, I was a very different ‘confident’. While Ray Clemence was still at the club, a journalist interviewed us both. During that interview, Ray said he had come to Liverpool and learned from his predecessor, Tommy Lawrence, for two years before replacing him. I laughed and said, “I’ll be taking your place way before that.” I wasn’t being disrespectful; I just wanted to show how confident I was.

I’m sure that raised a few eyebrows. A lot of what I did raised a few eyebrows. In my new home in the city, I had a zebra skin on my floor and in the front window, so that you could you see it from the street. I also had a leopard skin and a stuffed leopard head. I was from Africa – these things were normal to me. But I soon received a letter from the animal rights people, demanding that I remove the leopard or they would fire bomb my house. I obliged, putting it in my cellar. I was in a new country and I respected that.

I was seen as different on the pitch, too. I liked to use my whole penalty area. I could use my hands anywhere in my area, so that’s what I did, even if it meant venturing far from goal. Sure, I dropped a few, but I always backed myself.

In my first two seasons, I made mistakes which knocked us out of the European Cup. That was hard to get through. I’d stand in front of the vast Kop and hear the odd comment. In general, the fans were brilliant and encouraged me, but in the press and elsewhere, I could sense the doubters were there.

Whistle while you work

The army had taught me so much. I’d command my area as I had in the war. It was mine. This was my natural game. The defenders had to get used to my way of doing things. So, I’d whistle at my full-backs.

In the bush, you never shouted, for fear of being shot, so you learned to whistle. You learned different birdsong and how to use the sound of crickets at night. Soon, Alan Kennedy at left-back knew to respond to one sound and Phil Neal at right-back knew to respond to another.

I settled into life at Liverpool and the English game. I won trophies – lots of them. I became a senior player, dishing out the stick to young, new footballers while, I hope, ultimately helping them to settle in.

War gave me a sense of perspective; a sense of life. I can’t undo what happened, nor unsee the horrors I witnessed, but war taught me how to live for today. You can’t ever worry about the past.

Interview: Leo Moynihan • Illustration: Gavin McBain

This feature originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of FourFourTwo.