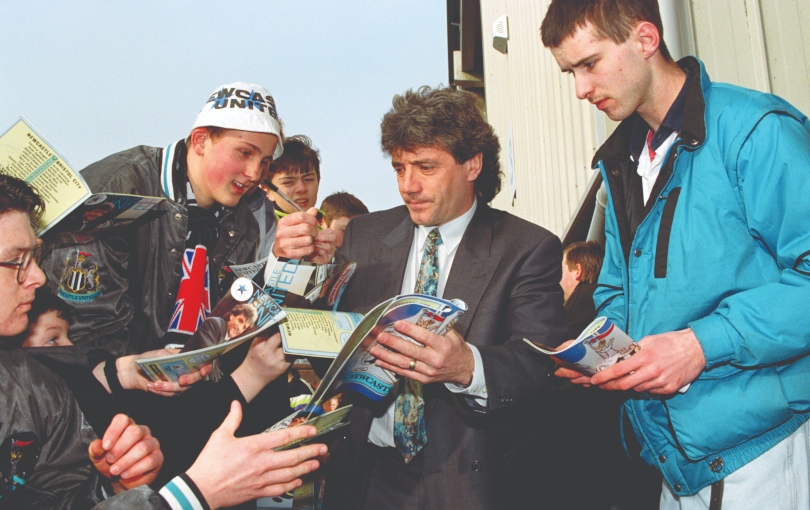

Kevin Keegan on Newcastle's 1995/96 Premier League challenge: “I still have nightmares about how we threw the title away”

Twenty-five years on from Kevin Keegan's infamous "love it" moment, King Kev explains exactly how Newcastle blew a title that should have been theirs

This Kein Keegan feature on Newcastle first appeared in in the May 2019 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe now and get your first five issues for £5!

On the final day of the 1995/96 season the Premier League trophy was at St James Park, but we never got to see it. The league had brought a replica just in case we beat Tottenham in our final game, and Manchester United lost at Middlesbrough.

But we could only draw, while United comfortably won 3-0 and were presented with the real trophy on the Riverside pitch.

We never saw the replica; it was hidden in the bowels of St James Park, and then whisked away without us ever catching a glimpse. For large parts of the season we had one hand on the Premier League trophy - we were twelve points clear of United at the top of the table and playing incredible football - but we just couldn’t get both hands on it.

When I look back at that season now, there’s some pride, but I still have nightmares about how we threw it away.

The Magpies' rise

In 1992, Newcastle had been in a very different position: bottom of the old Second Division, having won only six of their 30 previous games under Ossie Ardlies, and with the worst defence in the entire league. There were even fears they could fold.

At that time I had only just returned to England after spending seven years in Spain following my retirement from playing in 1984. While living in Marbella I almost completely forgot about football. For all that time, I barely watched it on television, and only went to see two games live. To be honest, I felt I could live without it.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Instead, I played so much golf that my daughters thought I was a golf pro, and didn’t realise I had anything to do with football, but I discovered it is possible to have too much sunshine and golf, and we came back to England for our daughters’ education.

There was no grand plan beyond that, no intention to get back in to football, until one day early in 1992 when out of the blue I received a call from the Newcastle chairman Sir John Hall.

He asked me to become Newcastle manager. “The two people who can save Newcastle are talking right now, you have got the passion, and I have got the money,” he told me. I came off the phone and told my wife Jean, “I know you’ll take it,” she said. She was right.

Maybe if it had been another club I would have turned them down, but this was Newcastle. My Dad was a Geordie, who always talked about Hughie Gallacher and Jackie Milburn, I had played for them as my last club, and knew what they demanded there.

I was excited about the club’s untapped potential, and what it would be like to be the manager to finally get it right there; to inspire those brilliant and loyal supporters who flocked to St James Park.

For all the romanticism, I still got a terrible shock when I walked back into the club and found it in a right mess.

The training ground was in a state of disrepair, and Terry McDermott, who I had brought in to be my assistant, even called it a “sh*t hole.” It was absolutely filthy; everything was covered in a layer of dirt - the dressing rooms, the gym, the baths and showers.

There wasn’t even a washing machine - the players had to take home their own kit to wash - and to save money on hotels, the club would not travel to a game the night before, only on the actual day.

The players didn’t feel valued, and so I spent £6,000 of my own money refurbishing the training ground. We basically fumigated it, cleaned it up and gave everything a lick of paint, and soon the players began to train and play with a sense of pride again.

When I arrived back at Newcastle I didn’t know many of the players, only really Micky Quinn and Ray Ranson, and knew virtually none of the other players in the Second Division.

On our first day of training I pulled Terry Mac up and said, ‘Wow, they are not that good!’ Some had ability, but a lot were way short, and the truth is even though I hadn’t played for seven years, myself and Terry Mac were the best two players in training!

But I just had a sense I could get the best out of them and keep them in the Second Division, which we confirmed on the final day of the season with a win at Leicester City, which saw us finish just four points above the relegation places.

Setting sights high

The following season I wasn’t interested in mere survival again, and on the eve of the campaign announced I would be taking Newcastle in to the Premier League. I am pleased to say I kept my word.

We were now a more confident side, and with better players like Rob Lee, John Beresford, Scott Sellars and Andy Cole, we won our first eleven games in the league, and eventually finished eight points clear as champions.

On entering the Premier League in 1993, I wanted to throw down a gauntlet to the big clubs, particularly the new champions Manchester United and their manager Alex Ferguson.

“Watch out Alex, we will be after your title,” I wrote in my programme notes, and I meant it. You can’t do that now. A team coming up from the Championship has no hope of challenging for the Premier League, but then you could really have a go.

We knew we were better than the bottom half of the Premier League, and should just aim to finish as high as possible. I set high standards, and it rubbed off on the players, and even on the board of directors.

So much so that our deputy chairman Douglas Hall felt emboldened to fly to Turin to sign Roberto Baggio from Juventus, who was arguably the best player in the world at that moment. He said, ‘Do you want to come with me? We’re going to sign Baggio.’

I said, ‘What? Are you just going to knock on the door?’ That was basically the plan! Unsurprisingly he got no joy in Italy. When he came back he said, ‘Can you believe they didn’t’ even see me.’

Yes, I could believe it, because we would have done the same!

But we did very well without Baggio, as I already had a dream strike partnership in Andy Cole and Peter Beardsley, who scored 55 league goals between them to help us finish third.

We were like a juggernaut by that stage; once we’d got going, we were powerful and picking up speed. We chipped away, improving the squad as much as we could. We were never going to get the very best players, they would always go to London or Manchester United, so we had to be smart and find players to improve us.

The following season in 1994/95 we stalled a bit and finished sixth, but half way through I had decided to sell Andy Cole to Manchester United. It came as a huge shock, but I had this instinct we had seen the best of him. We had had a few problems with him in training, he wanted a move, maybe he had been tapped up. When you have someone who doesn’t want to be there you have to move them on.

"I never argue when people say I wasn’t that into tactics - it’s true"

ON THE PLANE England Euro 2020 squad: Who's going?

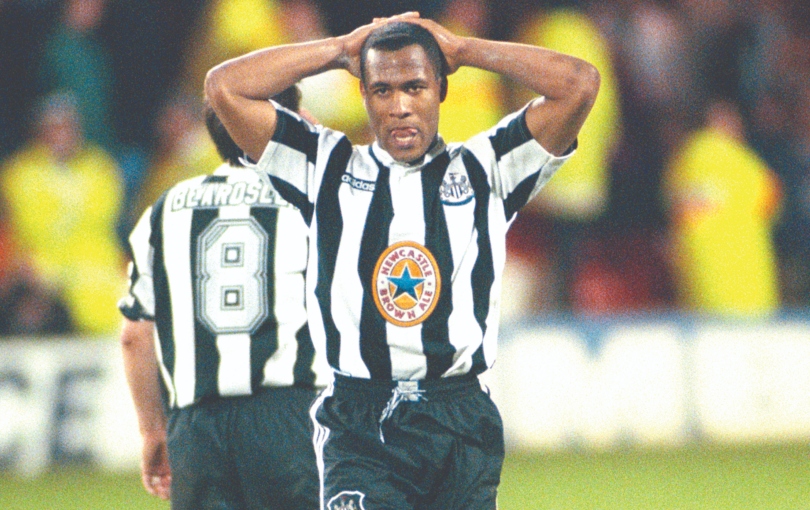

In the summer of 1995 we strengthened the squad once again to prepare for a full out assault on the Premier League title.

We brought in Les Ferdinand from QPR, who was 28, but hungrier than ever; I loved Philippe Albert, a Belgian defender at Anderlecht, who we thought we had no chance of getting, but we managed to convince to come over too.

David Ginola was 28 and had to get out of France; he was a wonderful crosser. At first some doubted if he would be better than Scott Sellars, but they needed just one training session to realise he was, and we were very lucky to have him at Newcastle.

It was like one of those Kaleidoscopes, you move a piece and then it all comes brilliantly in to focus. We won nine of our first ten league games at the start of the 1995/96 season to go to the top of the league where we stayed for the next eight months.

We played some wonderful attacking football, and I loved to sitting back and watching them from the bench. In many ways this team was an act of selfishness, because I created a team I wanted to watch. I could never set up a team to get a 0-0, that’s not football.

The players were enjoying it, there was just a positivity flowing through the club, because we knew we could beat anyone.

My team talks were quite simple. I would never argue with people who say I wasn’t that into tactics because it’s true. We had all these great players, so I didn’t want to restrict them; my mantra was to just let them play.

We looked at how we could cause the opposition problems. That was my style of coaching. We gave them freedom, a licence to play and be themselves. I would just say, “We have got so much ability, if we lose against these lot today the game has gone!”

Our attitude was it was all about us, it was about attacking. When I played for Liverpool, Bill Shankly was a massive inspiration to me, and said, ‘Go out and drop hand grenades all over the place.’

I played 4-4-2, with two strikers. We didn’t go anywhere with a defensive mindset. It might sound a bit gung-ho, and not all the players were happy - my central defender Darren Peacock even came to me and said, ‘Gaffer, is there any chance you could sign another defender?!’

12 points clear

By the middle of January we were 12 points clear of Manchester United in second place, and inevitably started to believe we could win the title. Everyone wanted us to win it, too. We got clapped on and off the field at many grounds.

On March 4th 1996, when United visited St James Park, our lead had been reduced to four points after a draw at Manchester City and a defeat at West Ham. This meant that a win against United would give us a lovely cushion of seven points, but a defeat would see our lead down to a single point. It was a huge game.

In the first half we absolutely battered them, ripped them to bits, but we couldn’t find a way past Peter Schmeichel, who saved everything we threw at him. We couldn’t believe it was still 0-0 at half-time. Six months later we would beat them 5-0 at St James Park, but I honestly believe we played better in this game, but we just couldn’t score, and in the second half Eric Cantona knocked one in to secure an unlikely 1-0 win. That hurt so much.

It was a stark reminder that United knew how to win those high-pressure games, and we didn’t. Until you’ve won something you are never sure you can finish the job, and they’d already done it over and over again, so they didn’t panic. We didn’t have that quality. If you look through our team, what had they won between them? Not much at all.

That game at Anfield

We beat West Ham in our next game before losing to Arsenal and then suffering the heartache of losing 4-3 against Liverpool at Anfield in that famous game. On a terrible pitch, we should have won that game twice over, but we came away with nothing.

In the final minute, Stan Collymore had scored Liverpool’s winner by beating Pavel Srnicek at the near post, which I always thought he should have saved. Pavel never thought I completely trusted him, and he was probably was right.

I always felt I could have had a better goalkeeper at Newcastle, but never got one. We didn’t ever have a truly great goalkeeper during my whole time there. That’s not an insult to Pavel, Shaka Hislop or any of the others, it’s just the way it was. If we had Peter Schmeichel in our goal we would have won the league, even if he might have been a little bit busier playing for us.

There’s no use pretending we didn’t mentally collapse towards the end of the season. We played under incredible tension. Chances were dropping to players you would expect to finish them, but we were snatching at them and missing them.

What would I have done differently? I can honestly say nothing. I am often told I should have been more defensive in the run-in, but I didn’t have the players to play another way. We were built to play attacking football, and had done that for three years.

What did people expect me to say to my team, ‘Ok guys, we are 12 points clear, we are playing fantastic football, but do you know what? I am now going to change the way we play. I am going to leave out David Ginola and put another defender on.’ I mean, come on! That just was never going to happen!

Of course, if someone said to me now you could turn the clock back and put two more defenders in, and play a few shit games, then you probably would just to get a trophy to Newcastle.

We had one way of playing that had got us to there, and we were stuck with it. We were the entertainers. Maybe history will judge that we did too much entertaining, and we should have shut up shop more, but I didn’t have the players to do that.

In February, I’d bought Faustino Asprilla from Parma for £6.7 million to help us win the league, and some have suggested his arrival was a reason for us falling short, because we started to lose games after that. But that’s not fair, that’s simply looking for a scapegoat, he also won us games we would have otherwise lost.

ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE "Collymore closing in!" - Martin Tyler recalls some of the greatest Premier League games he's commentated on

"I would love it...."

By the end of March, United had overtaken us at the top of the table and so we were now forced to play catch up. They had cemented their lead over us in April with a narrow 1-0 win over Leeds United, who had annoyed Alex Ferguson with their battling performance.

My understanding is that a furious Ferguson actually asked the Leeds manager Howard Wilkinson if he could go to the press, and more or less say that Leeds should be ashamed of themselves because they should play like that every week.

The sole reason he did that is because he knew we still had to go to Elland Road to play Leeds, and so he was suggesting they would not try as hard against us, and wanted to challenge them and their commitment, and throw down the gauntlet to them to beat us.

This really annoyed me because I thought Alex Ferguson was having a go at football, and suggesting that players wouldn’t try hard enough. The suggestion was that they only tried hard against him and Man United. I was not buying that. Everyone tries hard against everyone. That is what made me so angry.

On April 29th, after we had been to Leeds and won 1-0, I faced the Sky cameras for an interview and let it be known just how much he had annoyed me. This became known as my famous rant.

This is what I said: “When you do that, with footballers, like he [Alex Ferguson] said about Leeds…I’ve kept really quiet but I’ll let you something, he went down in my estimation when he said that. We have not resorted to that. But I’ll tell you, you can tell him now if you’re watching it, we’re still fighting for this title and he’s got to go to Middlesbrough and get something, and I tell you honestly, I will love it if we beat them. Love it!”

I don’t regret it even now. What he had said had really annoyed me, and I let that be known. It was just pure emotion. The interview was down the line with cans on my ears, and people always speak loudly with them on, you just don’t realise how loud you’re talking. I got on the bus afterwards, saw the interview and couldn’t believe I was shouting so much.

What does annoy me though is the myth that has built up that I lost Newcastle the title because of this rant, and that it made my players nervous and unsettled, which is simply not true.

United were three points ahead of us with a game to play, and while we still had two games to play, their goal difference was worth another point. The title had effectively already gone.

Ferguson crossed a line

On the final weekend they had to go to Middlesbrough, managed by a former United great Bryan Robson, and get a win, whereas we had to hope they lost that, and beat both Nottingham Forest and Tottenham in our final two games. It was never going to happen.

Sir Alex crossed a line, and therein lays the difference between me and him, and that’s how he won 13 league titles and I won none.

I don’t hold a grudge against him. I wouldn’t say we’re friends - we don’t go out for dinner, we’ve never been close - but there is a mutual respect there. He has since phoned me up and asked me to do a favour for a charity his friend runs, which I did.

People say we lost that league, but United won it, look at their record after Christmas. They just kept winning. On that final day they won again at Middlesbrough, while we could only draw at home with Tottenham to finish four points behind them in the table.

The whole mood was different that day, myself and the players knew we had gone. At the final whistle I hated doing a lap of honour, because I didn’t feel it was justified. I get you have to thank the fans at the end of the season, but the disappointment was so intense I didn’t want to walk around like that.

At the time we had nothing to show for a fantastic season, as back then you didn’t even get a Champions League place for finishing second, but on reflection I am still proud of what we achieved.

They say no one ever remembers who finishes second in the league, but people remember us for doing it that season. We were everyone’s second favourite team. They will always remember the entertainment we gave them, and the way we played.

Interview: Sam Pilger

This article first appeared in the May 2019 issue of FourFourTwo

Kevin Keegan: My Life in Football is published by Macmillan and out now

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and get your first five issues for just £5 for a limited time only - all the features, exclusive interviews, long reads and quizzes - for a cheaper price!

NOW READ

QUIZ Can you name Manchester City's top 50 most expensive signings?