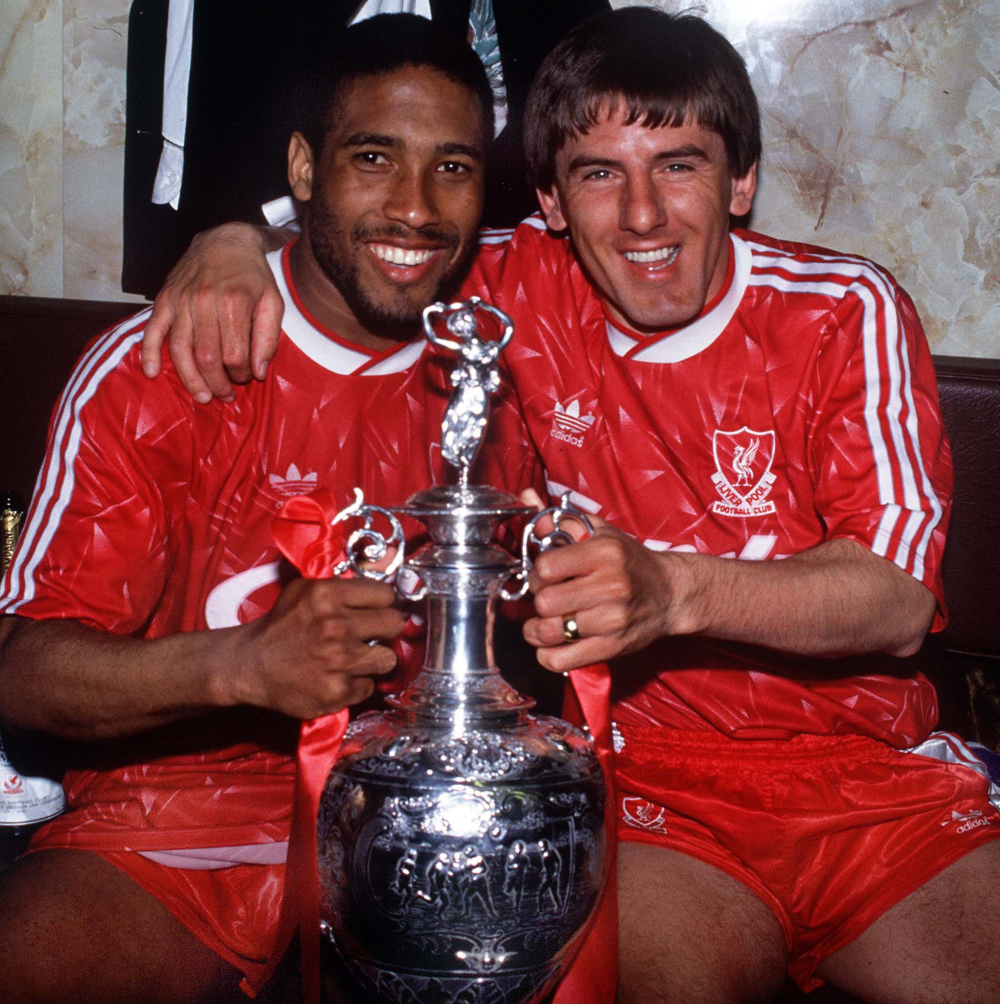

How the Liverpool empire came to crumble – the whole story of the Reds’ last title win, 30 years on

On April 28, 1990, Liverpool won their 18th league title. It was a dominance over English football few thought was about to end

This feature first appeared in the April 2020 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe now to get the first five issues for £5

When you’ve been an unparalleled leading actor for decades, it’s hard to play a bit-part role in someone else’s Hollywood ending. A proto-“Agueroooo” moment a week before Sergio’s first birthday, Arsenal’s title-sealing 2-0 victory at Anfield on Friday May 26, 1989 formed the emotional peak of Nick Hornby’s seminal book Fever Pitch and its film adaptation. For Liverpool, though, this was not in the script.

For once, the overdogs here had sympathy: the Reds were meant to win the league and help their city to overcome the searing pain of Hillsborough, six weeks earlier. But George Graham’s Gunners were no one’s patsies, and Michael Thomas’ stoppage-time goal snatched them the title on goals scored.

“In the changing room afterwards, it was hard to comprehend the loss,” ex-Liverpool midfielder Ray Houghton tells FourFourTwo. “The dressing room was devastated,” adds right-back Barry Venison. “You still didn’t really know what had happened. There were strong words in there... a lot of shouting.”

But there was also a lot of experience. The club had won nine of the previous 13 league titles. Manager Kenny Dalglish and captain Alan Hansen had been present for seven of them; coaching staff such as Roy Evans and teak-tough Ronnie Moran, for decades. They always took the long view. “That night was difficult,” says John Barnes, the team’s chief dangerman. “But it was forgotten about the day after, to raise ourselves and go again.”

Due to Everton’s title triumphs in 1985 and ’87, the trophy hadn’t left the city since 1981. Just as 23 years later, when an eight-year arrangement between Manchester United and Chelsea was interrupted by some noisy neighbours, the emergence of a new rival focused minds and increased determination.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“The quality in the squad was obvious and the mentality that the players carried was unbelievable,” reflects Houghton. “They all believed they were the best, simple as that.”

“Liverpool were just a winning machine,” concludes Venison. “They would never say, ‘We expect to win the title’ – Kenny would never utter those words – but there was always a desire and belief it would happen.”

Compared with today, Anfield in 1989 was similarly terrifying to visit but very different to behold. As the full Taylor Report wasn’t released until January 1990, the Kop was still a terrace. The Anfield Road End remained a single-tier, as was the stand then known as the Kemlyn Road. Although refurbished in 1973, the Main Stand dated back to 1906 – and hidden at its centre was the Boot Room.

This literally-named think-tank was where Bill Shankly, Bob Paisley, Joe Fagan, Ronnie Moran, Roy Evans and others had planned world domination over a drink. When Fagan retired in 1985, haunted by Heysel, Liverpool had turned to Dalglish as player-manager.

A Bonaparte in boots, he led them to a first Double but the next season ended trophyless – for only the second time in 12 seasons. So, with his own playing career effectively over and Ian Rush off to Italy, Dalglish hired John Aldridge, John Barnes and Peter Beardsley, who then shredded the First Division. Rush returned a year later and bagged a brace as Liverpool won an all-Merseyside 1989 FA Cup Final, but then came that twist ending against Arsenal. And as Venison knew, “Even if you won the FA Cup, if you hadn’t won the league, too, it was a huge disappointment.”

Liverpool’s main summer business was to hire a sidekick or substitute for 34-year-old Hansen, whose knees were crumbling after nearly 600 games for the club. Manchester United laid on a lunch for Fiorentina’s Glenn Hysen, but Liverpool got him for £600,000. Then, amid talk of a £20 million takeover by Michael Knighton, United instead broke the British record for a defender on the £2.3m Gary Pallister. Forces were assembling.

Unlike United, whose trophy haul from the previous 21 seasons totalled three FA Cups, Liverpool needed evolution, not revolution. It wasn’t a young team – Steve Staunton and the promising David Burrows aside – but nor was it creaking: outside of the Hansen/Hysen axis, the oldest regular outfield player was Beardsley (28). The spine was steeped in the Liverpool Way, from Bruce Grobbelaar in his 10th season to Rush in his ninth, via Hansen (13th) and Ronnie Whelan (11th). These were Europe-conquering medal-hoarders – and they wouldn’t relinquish their perch easily.

Liverpool and Arsenal swiftly reconvened in Wembley’s four-way Makita International Tournament, Arsenal winning 1-0 thanks to Steve Bould’s bonce, then again a fortnight later, again at Wembley, as Liverpool lifted the Charity Shield. Although Beardsley’s goal was enough, they should have scored more and never looked like conceding.

By contrast, Arsenal looked jaded, and did so again when losing their league opener 4-1 at Old Trafford after Knighton’s ball-juggling warm-up act. Down the M62, Liverpool saw off Manchester City 3-1 and Rob Hughes of the Sunday Times asked, “Is it too soon to say the holiday is over; that the championship is returning to the place where it has rested 12 times in 17 seasons? I think not.” John Barnes scored first in what would be his deadliest season, with 22 league goals (second only to Gary Lineker) and 28 all told. At club level, ‘Digger’ – a nickname inspired by a character from Dallas, suggesting that the TV soap’s 20 million UK viewers included pro footballers as well as bored housewives – was untethered from his role as left winger. He frequently inhabited the spaces Dalglish used to occupy, dropping into holes created by defences wary of Rush. Barnes gives FFT a (slightly) more recent comparison: “I liken it to Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole. Dwight got more goals than Andy one year, but Andy was the No.9 goalscorer. I outscored Ian that year but he was always the centre-forward.”

In midweek, Barnes opened the scoring again at Villa Park, where his former Watford manager, Graham Taylor, curiously selected as his opposite number at right-back Andy Comyn: a 21-year-old who had just arrived from sixth-tier Alvechurch. Yet Villa secured a 1-1 draw through a young David Platt, and Liverpool’s woes continued on Luton Town’s plastic pitch as the misfiring Rush was denied four times in a stalemate.

Unusually for the time, Liverpool then had a fortnight off domestic action. The FA had decreed a free Saturday ahead of England’s must-not-lose qualifier against Sweden, and Liverpool were excused from the previous midweek schedule because they had been booked for a friendly at Real Madrid. The rare foray to face top-class European opposition must have felt as piquant as the programme cover incorrectly describing the visitors as ‘Campeon de Inglaterra’. Liverpool lost at the Bernabeu but the break did them good: once Hysen had skippered Sweden to another 0-0 draw with England, now best remembered for the health-and-safety nightmare of Terry Butcher’s blood-soaked shirt, a 3-0 victory at Derby County ended Rush’s drought. Then came a result to ring down the ages.

Any win at home to newly-promoted Crystal Palace would have vaulted the Reds above Millwall, surprise early leaders. The 9-0 scoreline, however, was an unveiled threat. “We thought, ‘It’s unreal – it’s just so easy’,” Nicol told FFT. “Usually two halves are never the same, but that day we put on a clinic. It could have been 15-0.”

“Liverpool could be relentless,” Houghton says today. “Sometimes 1-0 was enough, but other times we could take teams to pieces. There were eight different scorers against Palace – that shows you the strength we had as a squad and how goals could come from any area of the pitch.”

At 5-0, Liverpool were awarded a penalty. Barnes was an able taker, but John Aldridge was bench-bound and nearing 31. Dalglish had accepted an offer from Real Sociedad for the diehard Kopite, who was aghast – “I had scored 63 goals in 104 games and he opted to sell me,” he told FFT. Dalglish insisted it was for the striker’s pension pot: “You’re at a premium now and can cash in.” With the deal imminent, Dalglish unleashed ‘Aldo’ to slot home the spot-kick with his first touch. At the final whistle, he lobbed his shirt and boots into the Kop. “I must admit that I had to brush away a few tears,” he recalled.

Four days after hitting nine goals at home to Palace, Liverpool were held to a goalless Anfield draw by Norwich City and neighbours Everton went top. But it was rectified a week later on derby day. While Manchester City were whupping United 5-1 at a manic Maine Road, Liverpool were much less considerate guests over at Goodison Park. Former Anfield schoolboy Mike Newell watched his opener get cancelled out by a Barnes header (“He was incredible in the air,” says Venison), then Rush – who had scored 21 goals in 23 Merseyside derbies – added two more within three second-half minutes.

A fortnight later, Liverpool faced a very different kind of testing trip, to Wimbledon’s Plough Lane – “the bludgeon against the rapier,” as the Sunday Times described it. While Hysen quietened John Fashanu, Barnes set up both goals in a 2-1 win. “It didn’t matter how you wanted to play against Liverpool – they were up for the challenge,” explains Houghton. “They could mix it with physical teams and could outplay the teams that tried to play against them.”

Then the wheels came off. A Southampton team including a young Matt Le Tissier (21), Rod Wallace (20) and Alan Shearer (19) made merry at The Dell, triumphing 4-1. It was only Liverpool’s second loss since New Year’s Day, but the next one came much quicker with an immediate League Cup defeat at Highbury. And, after beating Tottenham in the first live TV game of the campaign – on October 29 – the Reds lost 1-0 at home to Coventry City (Dalglish raging, “I won’t accept that as an acceptable standard for this club”) and then 3-2 at QPR. Liverpool had lost four in five.

Everywhere, old orders were crumbling. On the night Liverpool lost to Arsenal, Chancellor Nigel Lawson’s shock resignation gave Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher a body blow. Two nights before Liverpool lost to QPR, the Berlin Wall came down. As Thatcherism wobbled and the Cold War thawed, Liverpool’s loss of domination felt like another ending. But over the years they’d developed a counter-attack.

“When things weren’t going particularly well,” says Houghton, “we had a ‘full dog day’ with a couple of beers. If anyone felt another player wasn’t pulling their weight, you’d tell them. Then it was a case of getting back to winning ways.” For the gaffer, “Such sessions were vital for camaraderie... I encouraged the full dog days – as long as none of them ended up in jail.”

After a dogged 2-1 victory over Millwall at the (old) Den, with Jan Molby acting as sweeper, Liverpool were forced to confront demons in their following two matches.

In a televised Anfield tussle against Arsenal towards November’s end, Liverpool overcame Venison’s early concussion and Barnes’ saved penalty to win 2-1 through Steve McMahon’s drive and Barnes’ excellent free-kick.

More soul-searchingly, the next midweek fixture brought the unavoidable return to Hillsborough. The 95 dead – Anthony Bland would become the 96th in 1993, after nearly four years in a coma – were commemorated ahead of kick-off with wreaths placed at the closed Leppings Lane terrace. “It was one of those occasions when you just wanted to get through it,” recalls Houghton.

Dalglish detested every second of it. Having attended so many funerals and felt the pain etched onto the community, he found the night “really difficult, really distressing... we couldn’t get in and out quick enough.” The 2-0 loss mattered little in the greater context: “We fulfilled our obligations, took the defeat and sped home.”

After the psychological barrier of returning to Hillsborough, Liverpool went 20 matches unbeaten. True, eight of them were draws – Liverpool didn’t win three league games on the bounce until April – but they could grind.

“Consistency comes from mentality,” says Barnes in reflection. “You have teams who play fantastically but then, because of their mentality, don’t play well in some matches. Inconsistency comes when we perform well, score goals and think we’re great, then all of a sudden we don’t play well in the next game because we’re a bit complacent.”

Liverpool set about the pretenders to their own crown. After a patched-up side won 4-1 at Maine Road, the Reds – with a changed XI for the 10th successive fixture – came from behind to hold challengers Aston Villa 1-1, before dismissing fellow rivals Chelsea 5-2 at Stamford Bridge. Blues boss Bobby Campbell said Liverpool would be worthy contenders for the forthcoming World Cup in Italy.

Not everyone was swept away. Manchester United, problematic visitors to Anfield during the 1980s, restricted the Reds to a 0-0 draw that could have been worse. Liverpool were four points clear at the turn of the decade, but January was clogged with FA Cup games, with Swansea City and Norwich both earning replays (and the Swans an 8-0 shellacking). In the league, Nottingham Forest and Luton were permitted comebacks in 2-2 draws, and February brought a new table-topper led by a familiar face.

Back in 1982-83, Graham Taylor had guided newly-promoted Watford to 2nd spot behind Liverpool. Now he was doing a similar job at Villa with his curious hybrid of experienced heads (elegant centre-back Paul McGrath and stylish midfielder Gordon ‘Sid’ Cowans) and fresh legs (goalscoring midfielder David Platt and winger Tony Daley). Between Christmas and late February, Villa won seven straight league games – not that Houghton was too bothered. “Liverpool never thought about any other teams; it was all about what we could do,” he tells FFT. “If we got a result, we didn’t have to worry about anyone else.”

With their schedules now staggered, the two sides traded places in March. Liverpool’s commanding win at Old Trafford – Barnes’ brace outweighing Whelan’s bizarre 25-yard own goal – was negated by a first league loss in four months at Spurs three days later.

But, while London burned in riots against Margaret Thatcher’s imminent Poll Tax and while residents of Manchester’s Strangeways prison staged their own three-week rampage, Villa stuttered. They took only one point from three matches, so Liverpool’s narrow wins at home to Southampton and Wimbledon gave them the box seat as their attention turned to an FA Cup semi-final with Crystal Palace.

After the Anfield annihilation, Dalglish had been sympathetic: “The next day, I dropped Palace manager Steve Coppell a supportive letter, saying it was a freak result and I knew they’d go on to have a good season.” And so they did, climbing away from the drop zone thanks to the acquisitions of commanding centre-back Andy Thorn and Nigel Martyn, the country’s first £1m goalkeeper. But with Liverpool top and Palace 15th ahead of their final-four meet, the leaders were backed to secure an historic second Double which had narrowly eluded them for successive seasons. The Eagles, though, refused to bow.

Houghton reasons: “When you inflict a big defeat on an opponent, they’ll be even more determined to get something against you the next time. It hurts them.” Palace took inspiration wherever they could. They invoked the previously unbeatable Mike Tyson’s recent knockout by underdog Buster Douglas. En route to Villa Park, a member of the club’s catering staff pointed out a sign that read, ‘With God, anything is possible’. At half-time they were 1-0 down, but Thorn – who helped underdogs Wimbledon to beat Liverpool in the final two years earlier – knew the fabulous could be fallible.

After Mark Bright’s 46th-minute equaliser, Palace went in front through Gary O’Reilly. The Reds levelled and then led as McMahon and Barnes scored in quick succession, but Andy Gray – a different Andy Gray – made it 3-3 to force extra time on a baking April day.

“We had a number of significant players affected by injury that day,” says Houghton in mitigation. “I should have been taken off at half-time, as I was carrying an injury, but Staunton came on for Rush, who was also injured.” Beardsley was later diagnosed with a stress fracture of the knee.

In contrast, Crystal Palace – whose starting XI averaged 25 years of age to Liverpool’s 29 – were raring to go. Coppell, a proud Scouser, sent them back out with the words, “This is your time – you have to grasp it. You’re fitter, younger and hungrier.” As Thorn nodded on Gray’s corner-kick for Alan Pardew’s winning header, 4-3 avenging 9-0, Dalglish was left to muse on that letter to Coppell: “Not one of my wiser decisions.” “

Three days after the semi, Liverpool returned to Selhurst Park to face the Eagles’ tenants, Charlton Athletic. Israeli loan striker Ronny Rosenthal marked his first start by scoring a perfect hat-trick, before notching at home to Forest and changing the game at Arsenal. The hosts were the better side but as speedy subs Rosenthal pushed them back, Barnes’ late equaliser snatched the trophy from the holders’ hands. “We knew we’d win it then,” said Molby, Villa having lost at Old Trafford.

Rosenthal’s fifth goal in five games started a 4-1 victory over Chelsea, just after UEFA’s Lennart Johansson had indicated that their blanket ban on English clubs would end that summer. Although Liverpool would remain banned for a further season, this was closure of a kind for the horror of Heysel.

They clinched the title at Anfield in a style befitting the campaign, recovering from Roy Wegerle’s opener for QPR to grind through and win 2-1. Villa drew at home to Norwich. “I wouldn’t call it a vintage season,” mused Molby. “I don’t think anyone looks back and says, ‘Weren’t we brilliant?’ the way they do with the ’85-86 or ’87-88 teams.” It recalled Graeme Souness’ remarks six years earlier as Liverpool won the league with a 0-0 draw at Notts County. “Maybe by our standards we didn’t deserve to win the league this time,” said the Sampdoria-bound skipper, “but by everyone else’s standards we did.”

Grobbelaar threw his boss in the communal bath, but Dalglish had his own celebration in mind. For Liverpool’s midweek victory over Derby at Anfield, the 39-year-old put himself on the bench: “For the first and last time in my career, I pulled rank.” He brought himself on for the last 20 minutes to make his 502nd and final Liverpool appearance, on the night they lifted the trophy for the 18th time.

Liverpool rarely stood on ceremony, though. “Winners’ medals came in a big cardboard box that Ronnie Moran put on the treatment table,” reveals Houghton. “He went around the room and asked if you’d played enough games. If you had, he’d throw you a medal.” “Ronnie and Roy Evans made sure nothing changed in our attitude,” says Venison. “The first thing you heard after patting yourself on the back was, ‘Hey, bigheads, get your mind on next season – this one’s over’.”

Houghton adds, “It was a case of, ‘Put it in your cabinet and forget it... it’s about what you do next season’. It was relentless.” The club didn’t even plan an open-top bus tour. History has a habit of moving on. Liverpool had reasserted their dominance, but it didn’t last. Dalglish, by his own admission “almost exhausted”, nearly quit that summer, and in February – three months after Thatcher was toppled – the Scot became Liverpool’s second boss in a row to leave haunted by a disaster.

After considering Alan Hansen, Liverpool plumped for Graeme Souness in April 1991. A new broom with plenty of bristle, “Graeme wanted to transform the club and he wanted to do it yesterday,” says Venison. “There were a lot of immediate, dramatic changes.”

Not far away, his similarly confrontational compatriot Alex Ferguson had also initiated an unpopular overhaul – but that was rooting out satisfaction with mediocrity, which didn’t apply to Liverpool. A month after Souness started work, and a year after beating Crystal Palace in the FA Cup final, Ferguson lifted the Cup Winners’ Cup with Manchester United.

In 1993, a part of footballing history was wiped when renovation work on Anfield’s Main Stand required the demolition of the Boot Room to accommodate a revamped press room. The journalists didn’t spend long listening to Souness there: he resigned in January 1994 and was replaced by the Boot Room’s own Roy Evans, a new man from the old guard. He’d go on to win the League Cup – but Liverpool would have to wait a while longer for the title-winning magic to return.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!

NOW READ...

LIVERPOOL Why Sadio Mané is the most captivating footballer in the Premier League

PROFILE The best right-back in the world? How Trent Alexander-Arnold is reinventing the full-back

QUIZ Can you name the top 50 clubs according to UEFA coefficient?

Gary Parkinson is a freelance writer, editor, trainer, muso, singer, actor and coach. He spent 14 years at FourFourTwo as the Global Digital Editor and continues to regularly contribute to the magazine and website, including major features on Euro 96, Subbuteo, Robert Maxwell and the inside story of Liverpool's 1990 title win. He is also a Bolton Wanderers fan.