Liverpool's back three play to each other's strengths

How Rodgers is using Sakho, Skrtel and Toure...

Towards the end of Swansea’s debut Premier League season in 2011/12, Brendan Rodgers found himself without first-choice right-back Angel Rangel for the visit of Wolves.

Lacking a sufficient reserve in that role, he chose not to use someone out of position, instead experimenting with a 3-5-2 system. Swansea were no longer playing for anything, and Wolves were already relegated. So, thought Rodgers, why not try something new?

The system had mixed success – the game finished in an astonishing 4-4 draw, after Swansea had gone 4-1 up. Clearly, the way Rodgers deployed the system significantly strengthened the attack, but left gaping holes at the back.

In his first season at Liverpool, Rodgers’ most notable use of a back three was defensive, during the 2-2 draw at Everton. Here, he used it as a reactive measure, getting another centre-back onto the pitch to help deal with Leighton Baines’ crosses, and leaving Luis Suarez and Raheem Sterling high up the pitch, ready to pounce on the break. Had Sterling not missed a simple chance, Liverpool would have won the game and Rodgers’ switch would have looked like tactical genius.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

This season, he’s again turned to 3-5-2, although he’s doing it for a different reason. Suarez and Sturridge have a fantastic relationship up front. While a 4-2-3-1 system allows them to play close together, one is expected to drop off into the midfield to prevent Liverpool becoming overrun. Even in a 4-4-2, with a manager like Rodgers that demands good ball retention, one striker needs to become a supplementary midfielder.

Dynamic duo, troubled trio?

However, the 3-5-2 means Liverpool can use three central midfielders, while maintaining two strikers high up the pitch. It has brought the best from Suarez and Sturridge, who have hit 10 goals together in just four games with this system. But it’s caused problems at the back, where Liverpool have yet to keep a clean sheet playing 3-5-2. Essentially, it’s like that Wolves game all over again.

“When we tried it last year, we looked at it in training and then played it in a couple of games,” says Rodgers. “But you have to see it under pressure and have to see where you need to adapt things. The players have carried it out really well in the last couple of games. It can be a system that works for us, but what doesn't change is our idea of the game, how we want to pass, how we want to be aggressive in our attack.” But how does the system suit the three centre-backs?

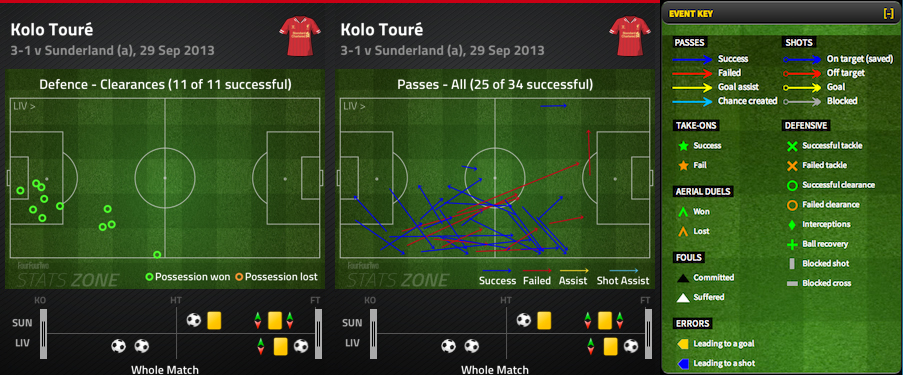

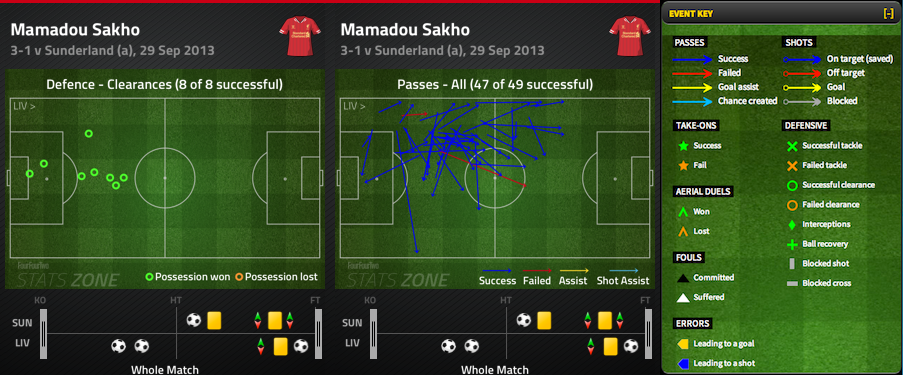

First, Rodgers is fortunate to have two players very comfortable playing on either side of a three-man defence: Kolo Toure and Mamadou Sakho. At Sunderland in the first league game when Liverpool used this system, right wing-back Jordan Henderson played an advanced role as more of a midfielder, whereas left wing-back Jose Enrique played more like a full-back, so there was a lop-sidedness to the way Toure and Sakho played. Toure played wider, covering the space in behind Henderson, whereas Sakho looked like a centre-back for long periods, playing much narrower. It was a 3-5-2, but a compromised 3-5-2.

Since then, the system has been more traditional in nature. And while the key with a three-man defence is always finding players suitable for the ‘outside’ centre-back positions – adaptable defenders happy at centre-back or full-back, and therefore capable of moving across to the touchlines and taking the ball forward – the surprising beneficiary has been Martin Skrtel, who plays in the middle of the trio.

While the Slovakian was voted Liverpool’s Player of the Year in 2011/12 before Rodgers joined, he never impressed last season – making early mistakes, and being particularly bad in the cup defeat to Oldham. He simply didn’t seem Rodgers’ type – too cumbersome on the ball, and not quick enough to play in a high defensive line. It was widely expected that he would leave the club in the summer.

However, a back three suits him perfectly. The defensive trio shift laterally across the pitch from side to side: if the ball is in the left-back zone, Sakho moves across and Toure tucks into the middle; if it’s in the right-back zone, Toure moves over and Sakho covers the centre. The obvious consequence is that Skrtel never gets dragged away from the central zone, and can stay in the box doing what he does best.

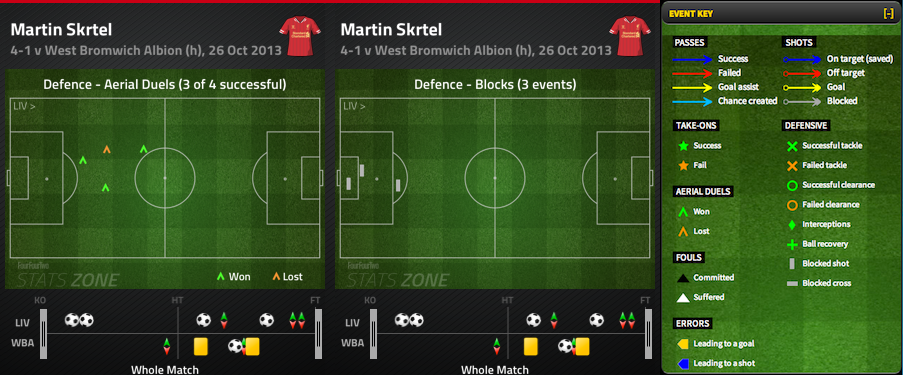

That was illustrated against West Brom, when he concentrated on winning aerial duels and making last-gasp, desperate blocks. He’s not the most cultured defender around, but he’s the type that is needed alongside Toure and Sakho.

The system also means Skrtel's limited passing range isn’t exposed too much – as shown in the game against Palace, where he simply knocked laterals balls to Toure and Sakho, inviting them to take the ball forward.

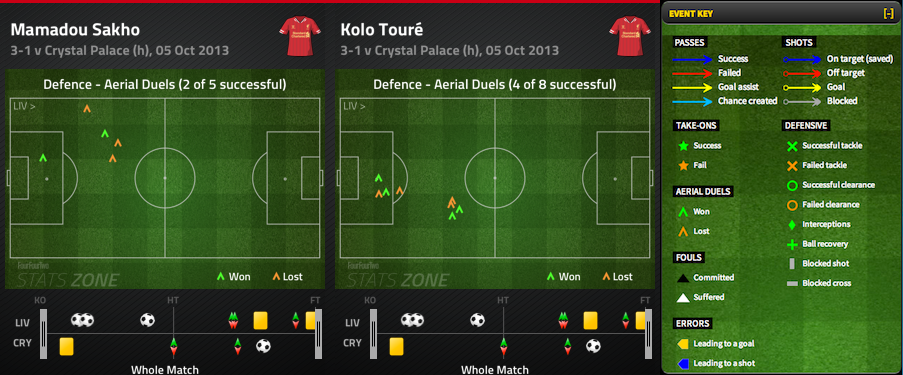

The only concern about the back three (in isolation) is the poor aerial duel records of the outside centre-backs – they regularly win less than 50% of these battles.

There are certainly wider concerns about the suitability of the system without the ball – Liverpool concede space down the flanks when the wing-backs become overloaded, and it seems more difficult for the team to press as a unit.

But the three centre-backs seem entirely comfortable in the system. This weekend’s contest against Arsenal will be the biggest test of the formation so far, but Rodgers can count on strong performances from Toure, Skrtel and Sakho.