Liverpool's last title win: How Kenny Dalglish led a grief-stricken club to glory in 1989/90

With the Reds seeking their first championship in 29 years, Seb Stafford-Bloor contextualises their remarkable post-Hillsborough success

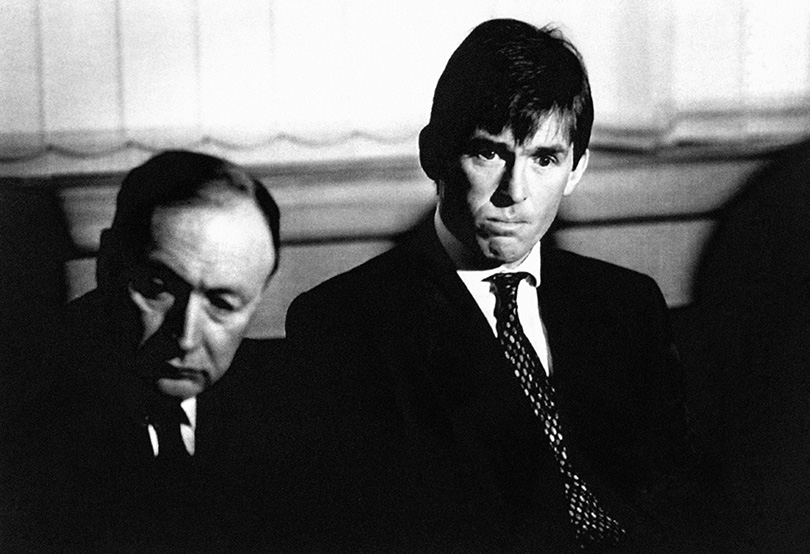

By February 1991, Kenny Dalglish had given all he had to Liverpool. The FA Cup replay with Everton, which ended in that thrilling 4-4 draw, is often identified as his breaking point, but Dalglish had made the decision to resign before he’d even arrived at Goodison Park. Broken by the emotional weight of the last 18 months, he sat alone in his hotel room the night before.

“Irrespective of the outcome against Liverpool’s oldest rivals, I was was going to tell them I was resigning,” he says in Mark Platt’s book The Red Journey: An Oral History of Liverpool FC. “If we'd won 4-0 I would still have resigned the next day. I could either keep my job or my sanity. I had to go.”

He went. And it was symbolically familiar: Bill Shankly’s abdication 17 years previously had blindsided supporters too. Relentless as the machine-gun attrition may have been, it was entirely different in tone.

Dalglish had been in the Ibrox crowd in 1971, when 66 supporters had died in a stairwell crush. In 1985 he had started the European Cup final in Heysel, where 39 lives were lost to a crumbling stadium, dreadful planning and needless violence. Finally, to complete the awful trifecta, he had emerged as the statesman of the Hillsborough tragedy, discarding his public reticence to help heal a community wounded by grief.

The righteous ending to that 1988/89 season, the one favoured by the gods, would have had nothing to do with Michael Thomas. But it did. Arsenal came to Anfield, got their two goals, and the First Division had its crescendo ending. A week earlier, Liverpool had been soothed by winning the FA Cup, but losing the league title was another blow to absorb; a lesser injury of a completely different type, but something else to recover from.

But Dalglish’s last great act at Liverpool is one deserving of greater reverence. Winning the First Division in 1989/90 remains the club’s last success of its kind and, given the atmosphere in which it occurred, a sizeable achievement.

A city in mourning

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The stories have been retold many times: the club that stood up for its community, literally opening its doors and welcoming people in to grieve. Dalglish and his wife Marina helped to coordinate much of the initial outreach. On the Monday after the disaster, he also led his players to the North General Hospital in Sheffield, where victims who would never recover lay and others fought for life.

The governor of Walton Prison even asked him to speak. Desperate to calm his prisoners, many of whom seethed in response to The Sun’s callous headlines, he called Dalglish. He went, of course, to where nobody ever wants to go.

They’re powerful tales. Hidden away behind them, though, was an assortment of private trauma. How important could football really be to Bruce Grobbelaar, for instance, who had heard the cries for help from behind his goal and pleaded with police to open the gates? Or Peter Beardsley, whose early shot had struck the crossbar, prompting that surge into the central pen? For any player on the Hillsborough pitch that day, making sense of their relationship with the game afterwards must have been extraordinarily difficult.

But that was Dalglish’s task ahead of that season: to embolden a team which had already begun to descend from its prime, but also to unravel that internal conflict. So, while 1989/90 may not have been a vintage campaign, what it represents is in a category of its own. In the abstract, it was the bookend to a perfect display of a football club’s function. In the months following April 1989, Liverpool provided solace. Over the next year, they clung to their sporting standard for the sake of restoring local pride. For what it comprises, the last title win really does warrant parity with any of that decade's other peaks.

Ups and downs

The campaign itself began with a tacit admission by Dalglish that the squad was on the wane. Liverpool snatched Glenn Hysen from under the noses of Manchester United, signed in response to Alan Hansen’s creaking joints, while Steve Harkness arrived from Carlisle. A late, unsuccessful attempt was also made to hijack Gary Lineker’s move from Barcelona to Tottenham, but with Ian Rush having returned from his own sojourn abroad with Juventus the year before, a lack of goals was not expected to be an issue.

In fact, from the Charity Shield onwards, Liverpool’s attacking gears seemed well greased. Beardsley began the season with his familiar effervescence, converting Barry Venison’s back-post cross at Wembley to enact immediate revenge over Arsenal. A week later, while Michael Knighton was juggling footballs at Old Trafford and Manchester United were humbling George Graham’s champions 4-1, Beardsley was driving Liverpool into the season proper. Manchester City’s Brian Gayle handled his goal-bound shot after just seven minutes on the opening day and John Barnes converted the resulting penalty. Beardsley would add a second and Liverpool eventually ran out 4-1 winners.

It was a fragmented season. It would take until April for Liverpool to win more than two league games in a row and August, September and October provided indications that it would be no gentle canter to the title. A marvellous solo effort by Barnes was only enough for a 1-1 draw at Villa Park and, a week later, Dalglish’s side fell foul of Kenilworth Road’s tacky plastic, being held to a goalless draw by a Luton team destined to avoid relegation only on goal difference.

The season’s high point was certainly decadent enough. Three days after another thrusting Beardsley performance had powered a 3-0 win at Derby’s Baseball Ground, Crystal Palace came to Anfield and were brutally thumped. Steve McMahon’s artful chip and Barnes’s postage-stamp free-kick were the pick of the nine goals, but buried within the day was also a curtain call.

John Aldridge would score his final Liverpool goal, coming on as a substitute and converting a penalty with his first touch. He was sold to Real Sociedad for just over £1m days later. Dalglish, writing in his autobiography, described the decision as a favour to Aldridge, and as a chance for a player in the last years of his prime to take advantage of his earning power.

'He's clinically dead, John'

San Sebastian is inviting at at the best of times, but it’s tempting to read between the lines. Aldridge was a native Liverpudlian for whom Hillsborough cut very deep indeed. In his own autobiography, he remembered returning home on the night of the disaster to his wife Joan, and being reduced to tears as the scale of Hillsborough grew steadily on the national news. Like many, the tragedy altered his perspective of the game and Real Sociedad, perhaps, represented a continuation of his career on more gentle terms.

“The thought of training never entered my head,” Aldridge wrote. "I remember trying to go jogging but I couldn't run. There was a time when I wondered if I would ever muster the strength to play. I seriously considered retirement. I was learning about what was relevant in life.”

Aldridge’s descriptions of those days are particularly bleak, and in those passages he certainly sounds like a man contemplating retirement. Like all his team-mates he was a regular at the funerals, giving a reading at the service of Gary Church, a 19-year-old joiner from Seaforth.

“Whenever I think of Hillsborough I am drawn to the story of young Lee Nicol from Bootle,” he wrote. “Lee was 14 but looked about 10. He reminded me of my son, Paul. Lee was in the middle of the crush at Leppings Lane but was still alive when he was pulled out. I went to see him in hospital. He looked a lovely kid. As he lay there in a coma, I whispered words into his ears. I asked the doctor about his chances of recovery. 'He's clinically dead, John.'”

Football is serious and important. At its core, though, it’s a pastime. Even for professionals and despite its pressures, the challenges it poses are relatively mild in the context of normal adult life. But these players had been exposed to a pervasive darkness, and loitering in those shadows would have been an unsettling conclusion: those fans followed us to this place, they came to watch me. It’s the torture of being inadvertently complicit.

Aldridge seriously considered walking away from the game. Grobbelaar did too. Even tough, stoic characters like Hansen and McMahon were emotionally shattered by the hospital visits, the funerals and the tragedy’s overpowering gloom.

Dressing room spirit

The season's dip came in October. At The Dell, Liverpool were undone by a 21-year-old Matthew Le Tissier, plus goals from Paul Rideout and two from a young Rodney Wallace. A Barnes penalty teased a comeback, but Le Tissier slammed the door, thundering in a back-post header to complete a 4-1 rout. More was to follow: before the end of November, Arsenal would dump them out of the League Cup and Coventry would sneak a win at Anfield, with Cyrille Regis heading past Grobbelaar.

But the stumbles frame the achievement in a certain way. Under normal conditions, self-pity is never far from a dressing room - and generally with little justification. These, clearly, were not normal conditions at Liverpool. Dalglish’s account of how he managed the atmosphere around the team is vague. He speaks fondly of Hansen’s rallying cry for “full dog days”, squad bonding sessions which spilled out of pubs and around dog tracks and race courses, but with sparing detail.

There’s little to be found in other accounts, either. A humbling defeat at Southampton and an embarrassing loss to Coventry are the kind of results that can gnaw at a group’s self-belief, particularly when the players are emotionally raw, and yet Liverpool retained a fascinating immunity.

By the end of the month, the club found themselves at the top of the table. Liverpool comfortably beat Millwall at The Den and then defeated Arsenal 2-1 at Anfield courtesy of Barnes’s fabulous free-kick, which teased cheating steps from John Lukic before swirling back across him and ramming into the top corner. Barnes had a sensational season. His 22 league goals deservedly won him his second FWA Footballer of the Year award in three seasons, and the craft and execution of his attacking play showed him at the very apex of his ability.

Elsewhere in the team, there were still troubling themes. While Hysen had been signed to cure Liverpool’s susceptibility to physical forwards, Liverpool remained vulnerable in the air. There was little evidence of them being regularly over-powered, but the organisation and understanding at the base of the defence had clearly declined. Statistics don’t bear that out - they finished the season with the best defensive record in the league - but while the side was still flecked with enough class to be recognisably Liverpool, errors littered the first half of the campaign. The goals they conceded weren’t troubling in volume, but they were disconcertingly atypical.

Return to Hillsborough

On November 29, they returned to Hillsborough. Before kick-off, both sets of players stood in silent remembrance in front of the empty base of the Leppings Lane terrace. From above, travelling supporters dropped bouquets down into the central pen, which were quickly and quietly gathered up and organised into neat, respectful rows. On the pitch, Sheffield Wednesday weren’t remotely sentimental, and a mesmerising Dalian Atkinson performance was at the heart of a deserved 2-0 win.

It's interesting that 1989/90 is paid so little attention in Dalglish’s autobiography. While that's hardly a surprise given the gravity of the preceding chapters, the year is almost glossed over, barely comprising five pages. Maybe it’s an indication of how time passed during that period of his life. Maybe it’s even indicative of how broad his focus had become and the declining importance he placed on arbitrary footballing detail. Or perhaps it’s because so many of the challenges faced were unseen and, consequently, had no obvious remedy.

In time, Kelvin Mackenzie’s lies were exposed and, at the time of writing, senior figures involved in the tragedy are facing trial. But one wonders about the hidden cost of the accusations. Those false allegations may have been published with diversion in mind, but they amounted not just to an attack on the truth, supporters of a particular football club or even fan culture itself, but on people from a specific part of the country. They were sustained for decades. Long after The Sun was being boycotted and Mackenzie had slithered away, the legacy of those fabrications remained in the broader media and in perceptions of the area itself.

While the true victims of Hillsborough were, of course, those who lost their lives and the families left bereaved, that deception likely had a far broader cost. It’s nobody’s place to speculate on what specifically it may have been, let alone almost 30 years later, but it would have been part of the atmosphere which that Liverpool - the team, their supporters and their constituents - had to slog through.

A remarkable triumph

Superficially, the side’s form from the turn of the year onwards stands comparison with any four months from the previous 10 years. They’d lose just once in the league, to a Paul Stewart goal at White Hart Lane, and reached the FA Cup semi-final, only for Crystal Palace to eliminate them in a topsy-turvy, seven-goal game at Villa Park. Within the subtext lay the imperfections, though.

How Hillsborough changed football forever

THIS is what being a fan in the 1980s was like – and what the Hillsborough verdict means

Whereas Liverpool teams of the past had roared toward championships imperiously, this side was blighted by neuroses. It showed in the loss of two separate two-goal leads to Nottingham Forest, in the failure to beat Luton home or away, and in the calibre of goals conceded to Wimbledon, Southampton and Everton during the New Year. Even on the day they clinched the title, Aston Villa’s failure to beat Norwich was only terminal because of a come-from-behind win which relied, in part, on an incorrectly awarded penalty.

But that doesn’t detract from the achievement, it just shows they were mortal; no longer a super team or directed by the all-seeing eyes within the Boot Room, but a fallible Liverpool who had to rage against the dying of their own light. Anfield 1989/90 was the last days of an empire and, like the great heavyweight who can still punch or the virtuoso who can still reach the highest notes, they went out for the crowd one more time and delivered.

A tremendous achievement, then. Diluted, perhaps, by the talent available and the assumption that Liverpool’s era would never end, but certainly magnified by what it took to deliver and what it cost its author.

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.