Long read: The making of Zlatan – friends and foes reveal the rise behind the legend

To some people he’s a cult icon; to others, a perpetual self-parody. FourFourTwo speaks to those who know him best in an attempt to understand who Zlatan really is – and whether he can help the Red Devils to rule again

Additional reporting: Marcus Alves, Arthur Renard, Alberto Santi

Manchester United’s players trudge across the training ground’s manicured lawns to the sanctuary of the changing rooms. But on this nondescript Lancashire morning, the squad’s newest foreign recruit doesn’t join them. Instead he approaches the manager, who’s under pressure to deliver domestic success after another limp campaign.

“I need two players,” he tells his boss, a greying disciplinarian well known for his all-encompassing desire to win.

“What for?” comes the manager’s perplexed reply.

“To practise.”

1998-99 Malmo: None

2001-02 Ajax: Eredivisie, KNVB Cup

2004-05 Juventus: Serie A (Later revoked due to match-fixing scandal)

2006-07 Inter: Serie A, Supercoppa Italia

2009-10 Barcelona: La Liga, Supercopa de Espana, UEFA Super Cup, FIFA Club World Cup

2010-11 Milan: Serie A

2012-13 PSG: Ligue 1

Two keen-as-mustard youth-teamers are soon dispatched to deliver crosses for the newbie, who spends the next half-hour smashing volleys past a helpless goalkeeper with unerring regularity. Word reaches the dressing room, who have already heard about their new team-mate’s reputation as a fierce trainer.

The following day, he has company. It’s the same the day after that. And the next day, and the next day, and in every session for the rest of the season, until the Red Devils lift the Premier League – their first top-flight title since 1967. They’d win three of the following four championships. The one year they didn’t, that fearsome, natural-born winner with the aloof shrug was suspended for a karate kick.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The God of Manchester

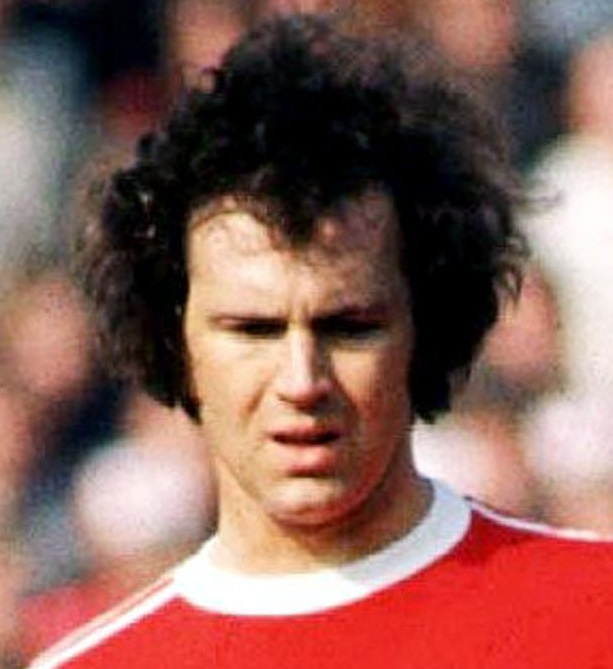

Eric Cantona’s impact on Manchester United should not be understated. His arrival in November 1992, at a club that had stagnated since their glory days in the ’60s, inspired nothing short of a revolution. Training had a new zip. Alex Ferguson’s squad had a new belief. Old Trafford had a new king.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, Manchester United needed to inject more blue blood into a listing giant. Jose Mourinho knew he had to redress the dour sterility of Louis van Gaal’s reign. Like Ferguson in 1992, he needed a winner with attitude. He needed Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

“I won’t be King of Manchester,” said the 35-year-old Swede with typical bombast, after Cantona had offered the role of prince to his stylistic successor at Old Trafford. Instead: “I’ll be God of Manchester.”

Really, Zlatan? Does someone in the autumn of their career, who has won league titles in four different countries, still have the stomach for the fight to back up his narcissistic caricature? Can one man really turn underachievers into title contenders?

Tough beginnings

Zlatan Ibrahimovic is a far better footballer than he was a thief. Growing up on the notorious Rosengaard estate, east of Malmo, he would pick bike locks for fun because it made him feel alive. One day, young Zlatan and a friend went to Wessels department store, halfway between Rosengaard and downtown Malmo. Immediately raising suspicions by wearing Puffa jackets in the middle of summer, they were caught stealing £120 worth of goods, including four table tennis bats. Ibrahimovic escaped a colossal telling-off from his father, Sefik, but only because he intercepted the letter that had been sent home to inform Sefik of his transgression.

A macho bricklayer-turned-caretaker, Sefik spent most of his time drinking beer and listening to music from his Yugoslav homeland, but he bonded with his son over Jackie Chan movies and old boxing bouts involving Muhammad Ali, George Foreman and Mike Tyson. Sefik and Zlatan’s mother, a cleaner named Jurka, had split up when the boy was two years old.

Small, thin and with a big nose, he hated going to Sorgenfriskolan school, largely because he had a lisp and found the idea of having a speech therapist humiliating

“My dad was never there,” Ibra recalled of his early days playing for local side FBK Balkan, populated mainly by immigrants from the former Yugoslavia. “I looked after myself. Maybe it did hurt. I can’t really tell.”

Such independence gave rise to a disrespect for authority that has never deserted him. Small, thin and with a big nose, he hated going to Sorgenfriskolan school, largely because he had a lisp and found the idea of having a speech therapist humiliating.

“I’ve been at this school for 33 years and he is easily in the top five most unruly pupils we have ever had,” Agneta Cederbom, Zlatan’s headmistress at Sorgenfriskolan school, once said. “He was a one-man show – completely outstanding in his field, and a prototype of the kind of child that ends up in serious trouble. I think things could have gone horribly wrong if it hadn’t been for the football.”

Yet football he had, earning his place at Malmo as an 11-year-old after his father had encouraged him to try out.

“I’m not exaggerating when I say that he played eight hours of football each day,” Ola Gallstad, Ibrahimovic’s coach at Malmo from 14 until 18, tells FFT. “He was living the dream. He barely missed a training session. He would go home and play at the concrete court by his house.

“He wasn’t exactly someone who got you to think, ‘Oh wow, this guy they must have brought down from heaven.’ Actually, another young guy called Tony Flygare got more attention at the time. It wasn’t until he was 16 that Zlatan really started to stand out.”

Troublemaker

Signed from Colombian club Millonarios after a complicated tug of war with Barcelona, the Blond Arrow established Real Madrid as the world’s greatest club side, able to buy the finest talent. He also opened the floodgates for more South American players to move to Europe, something that soon became commonplace.

Previously, he’d stood out for other reasons. Two parents tried to eject Zlatan – one of only two players of non-Swedish extraction – from the club for shouting at one of his team-mates. Then headbutting him.

“He came from a hard environment out in Rosengaard where you had to stand up for yourself,” Gallstad recalls. “Many have an image of him as ‘the bad guy’ but I don’t think Zlatan was a troublemaker – quite the opposite, in fact. When he was fired up, he’d be the one defending his team, standing up for his mates.”

Gradually, Zlatan became Malmo’s hottest prospect, and it was because of, not in spite of, that anti-Swedish mentality. Most Scandinavians are brought up on the concept of Jantelagen – a social democracy that roughly means everyone is the same – yet Ibra had always been fascinated by Brazilian football’s individualism, especially the brand of it displayed by Ronaldo. Even scoring a goal mattered less than a trick, a flick or a piece of skill.

In 2000 Malmo were at their lowest ebb, relegated to the second tier for the first time in their 90-year history, and Zlatan got his first-team chance. That season, film-makers Magnus and Fredrik Gertten were making Vagen Tillbaka (‘The Road Back’), a documentary about Malmo’s attempt to return to the top flight at the first attempt. Ibrahimovic, who’d made just six first-team appearances, was only 18 years old but already something of a cult hero. He fascinated them.

“We couldn’t use a lot of the Zlatan footage for the documentary, but we kept the tapes in our basement because it was so interesting,” Magnus tells FFT. “After Zlatan wrote his autobiography, we decided to release it. When we met him in those early years, we were really close to him. He was spontaneous and open to us.”

The footage is extraordinary. It perfectly captures a glorious mixture of adolescent bravado and uncertain angst at the future. Ibrahimovic is yet to properly fill out and carries himself like the gawky teenager he is. Shoulders hunched, he’s always irritated, and bounces from unintelligible mutterings on camera to excitable exclamations. Though the confidence is clearly there to see in his on-pitch dribbling, this figure is a million miles away from the uber-confident demi-god we see today.

The footage captures a glorious mixture of adolescent bravado and uncertain angst at the future. Ibrahimovic is yet to properly fill out and carries himself like the gawky teenager he is

“I can be difficult to get along with,” he says in one video. “Sometimes my team-mates get mad at me. It’s part of the game – it’s no fun if you can’t dribble. Football is supposed to be fun. If it isn’t, what’s the point?”

That season, Ibrahimovic established himself as the club’s first-choice striker, finding the net 12 times as the 1979 European Cup runners-up returned to the Swedish top flight. His Malmo team-mates, however, didn’t necessarily buy into Zlatan-mania.

“He has started to think he’s above the team – he’s not the star yet,” sighed captain Hasse Mattisson at one point. “If he starts juggling by the corner flag then all of a sudden he’s the new Diego Maradona. Well, we can do that, too, but we don’t.”

Magnus believes it is that same Swedish mistrust of difference. “Zlatan didn’t accept the hierarchy of how the first team worked,” he says. “I remember someone from another club saying, ‘Who does he think he is?’ I think there was some prejudice against him as well. Perhaps some players thought that Zlatan wouldn’t be smart or strong enough to make it at the top level.”

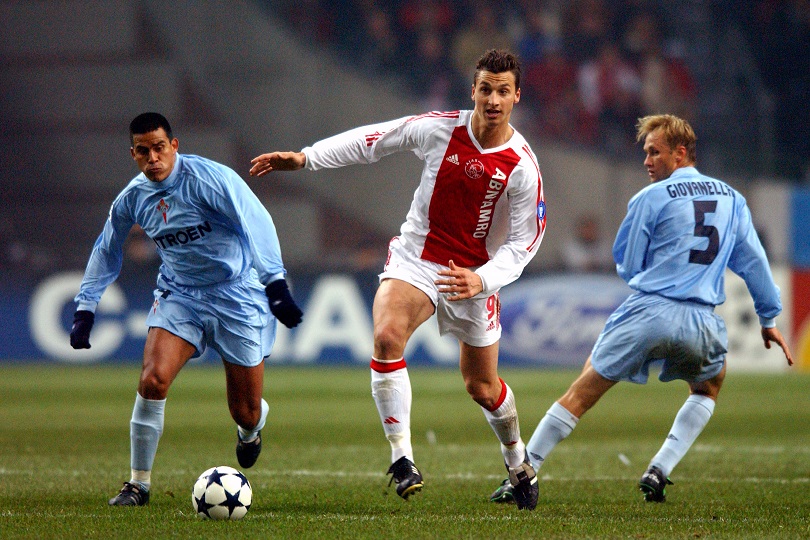

Amsterdam calling

Ibra wants to win in every training session, every practice match, and it was one such game that secured his move to Ajax

By the end of that promotion-winning season, 19-year-old Ibrahimovic would be sold to Ajax for €8.7 million. Dressing-room footage shows skipper Mattisson stunned after reading the newspaper, saying only: “Well, I guess I will have to congratulate him.” Grinning from ear to ear, Zlatan bursts into shot with a look on his face that screams: “I told you I was brilliant.”

“I don’t think Mattisson, who I know well, meant anything bad with it,” says Malmo youth-team coach Gallstad. “If a teenager comes in and is a bit tough towards those who are 30, then it’s natural they give him the eye. Not that Zlatan really cared about that.”

Ajax knew what they were getting: a radical, yes, who would always follow his own path, but also a born winner. If Ibrahimovic’s troubles with his older Malmo team-mates signify anything, it’s his unshakable desire to achieve – something reflected in his domestic record. Since leaving Malmo in 2001, he has won 13 of the 15 domestic league titles on offer during his time with Ajax, Juventus, Inter, Barcelona, Milan and Paris Saint-Germain. The path is pretty clear: wherever Zlatan goes, success inevitably follows.

This is no coincidence. Ibra wants to win in every training session, every practice match, and it was one such game that secured his move to Ajax. Malmo played a friendly against a semi-pro side in March 2001. The goal he scored that day – a solo run past three defenders, capped with a delicate finish – is still on YouTube.

“After watching for 15 minutes, I’d seen enough,” Leo Beenhakker, former Real Madrid and Netherlands manager who at that time was Ajax’s technical director, tells FFT. With Zlatan also on the radar of the club’s Scandinavian scout, John Steen Olsen, for at least 12 months, the Dutch side moved quickly to beat off competition from Roma while Fabio Capello awaited his chairman’s approval.

Beenhakker continues: “When we’d concluded the deal, I told him jokingly, ‘If you f**k me, I f**k you.’ But he looked at me and said, ‘No worries – I’ll not f**k you. I’ll make it happen.’ He showed unquenchable ambition and he had such willpower, like: ‘I will and must succeed.’”

After watching for 15 minutes, I’d seen enough

Beenhakker wouldn’t be left disappointed. “From the start, he trained very well and busied himself securing a place in the pecking order. I like that. Give me 11 of those personalities and you’ll win titles. They might be difficult off the pitch, but on it they will give everything for you.”

Talk to any of Ibrahimovic’s former team-mates or coaches and they will offer similar training stories. “He’s always been very serious during training,” Roberto Mancini, who managed Ibra at Inter from 2006 to 2008, tells FFT. “He knows he’s the best, and he’ll tell you that, but he’s the go-to guy if you want to win. He can be a tough player to handle, but I never had problems with him because he will make the difference. Every great player wants to win, and Zlatan’s no different.”

“He’s really boring,” laughs ex-Inter left-back Cesar Rodrigues. “You need to watch your every move around him because he’s so demanding. He wants everything to revolve around him; to be the centre of attention.”

Keeping team-mates on their toes

After rejecting boyhood idols 1860 Munich following an altercation in a youth event, the would-be Kaizer instead took his ball to ‘modest’ Bayern, securing promotion to the new Bundesliga in his first season – as a teenager – and the club’s first German Cup in his second. Dominance, both domestic and European, duly followed.

In one of his first training sessions at Ajax, Ibrahimovic showed talent and also his penchant for individuality.

“We played 11 vs 11, where only two touches were allowed,” recalls the Amsterdammers’ former Norway international, Andre Bergdolmo. “From the moment you had a third touch, you couldn’t pass it to a team-mate and were only allowed to dribble it by yourself. Zlatan touched it too many times and was reprimanded by the coaches.

“He was still inside his own half, but dribbled all the way to the goal. Before scoring, he stopped on the goal-line, put his foot on the ball and then boastfully asked: ‘Is it OK now?’”

Such exacting standards are expected across the Zlatan spectrum.

“He’s always complaining during training – it’s a part of him,” says his former Juventus team-mate, Emerson. “Someone who doesn’t know him might take it in a negative way. If you don’t give him the ball, he’ll get pissed off. But it doesn’t mean he’s a bad guy. He’s definitely not.”

At PSG, one youth-team player was told to “go home and write on the calendar that you trained with me, as this is the last time it’ll happen”. The Swede had been less than impressed with the youngster’s efforts.

It isn’t just easy targets in his sights, though. At Milan in 2011, bored midfield Rottweiler Gennaro Gattuso began throwing grapes across the dressing room at Ibrahimovic. “If you don’t stop that, I’ll put you in that f**king bin,” smiled Zlatan. Keen to see what would happen, Gattuso carried on. Ibra stood up, grabbed the Italian midfielder by the waist and dumped him in with the dirty kit and tape. Face first. The squad, Gattuso included, fell about laughing.

That said, Ibra doesn’t take too kindly to the shoe being on the other foot. Such a dominant win-at-all costs personality can’t come without confrontation in the dressing room. Of all the stories that have attached themselves to Ibrahimovic over the years, one stands out: the infamous scissor-throwing incident with Mido, at Ajax in March 2002.

The pair, who were firm friends, had argued throughout a frustrating 1-1 draw with PSV, each accusing the other of playing only for themselves. In Ibra’s mind, the Egyptian’s selfishness – regardless of his own – was damaging Ajax’s chances of victory.

Of all the stories that have attached themselves to Ibrahimovic over the years, one stands out: the infamous scissor-throwing incident with Mido

“They kept arguing all the way down the tunnel,” says Bergdolmo. “They were sat opposite each other in the dressing room. I was next to Zlatan. Then: ‘BANG!’ Mido had thrown a pair of scissors with all his strength, hitting the wall as Ibra ducked, missing his eye by a whisker.

“We all stopped. Zlatan’s face went white, his eyes turned black and he just flipped out. Other players and I jumped at him, trying to avoid a fight. If we hadn’t been there, anything could have happened.”

David Endt, who spent more than 30 years at Ajax as a player, youth-team coach and general manager, was next door.

“I still have those scissors in a draw! I knew this was something special,” Endt tells FFT. “The next day, we arrived for training more than a little worried. And who was sat there together but Zlatan and Mido, with their arms around each other? Mido laughed: ‘I could have killed you.’ And Ibrahimovic laughed with him. They solved the problem like hard lads in the street, with respect and understanding. They have that similar uncontrollable personality.

“Mido was a good player, but Zlatan also had the head to turn his talent into something more concrete. Zlatan had brains. Mido didn’t.”

Complex character

For all of the chest-out peacocking, Ibrahimovic has frequently been wracked by self-doubt, especially in his early Ajax days

Such stories feed the self-referential ‘I Am Zlatan’ persona that has taken on a life of its own. It even has its own digital avatar that participates in occasional web chats live on YouTube.

“Zlatan doesn’t do auditions,” the real thing told Arsene Wenger on trial at Arsenal. What did he get his partner, Helena, for her birthday? “Nothing – she already has Zlatan.” There are plenty more Zlatanisms.

The truth, however, is seldom so clear-cut. Ibrahimovic’s self-belief may be the central cog to his consistency, longevity and extensive trophy haul, but those who know Zlatan best – the real Zlatan – reveal a complex character who is a world removed from the caricature that often talks about himself in the third person.

First, let’s dispel those myths. Malmo’s director of football, Hasse Borg, advised him not to play in the trial match for Arsenal, telling Wenger that they either wanted to buy Ibrahimovic or they didn’t. As for Helena – the mother of his two children, whom he credits with turning his life around, and whose drive he once raked after doing wheel spins on it in his Porsche – Zlatan would never dare speak about her in that manner. It was an off-the-cuff remark about his one-time fiancée.

For all of the chest-out peacocking, Ibrahimovic has frequently been wracked by self-doubt, especially in his early Ajax days, when he was mercilessly derided as something of a joke.

“Every Monday after a match, he used to come into my office to talk,” says Beenhakker, the man who brought him to the Dutch club. “Zlatan’s human moments make for dear memories. We would talk about how to come back and work hard to be prepared for the next game.”

“Every time he left, he’d say: ‘I know I didn’t play well yesterday, but I’ll show everyone what I can do.’ His inner drive overcame his emotions. I have never doubted him for one minute.”

The dribble that so enchanted team-mate Bergdolmo in one of his first training sessions also infuriated his coaches

Ibrahimovic’s biggest struggle was adapting to Ajax’s one-size-fits-all approach to youth development, which always prizes the system over the individual. The dribble that so enchanted team-mate Bergdolmo in one of his first training sessions also infuriated his coaches.

“He struggled to lose this tendency to show off,” says former general manager Endt. “Too often, he missed chances or refused to play a simple pass to a team-mate who was in a better position.

“But we also had the wrong approach. There’s a tendency at Ajax to say that we know things better and to tell people what to do. This created a natural resistance with Zlatan, because his difficult childhood meant he mistrusted everyone. The rebel came out.

“After a while, I asked Sweden’s assistant coach, Tommy Soderberg, what to do. He said that you have to convince Zlatan you’re not the teacher and he’s not the pupil. Give him responsibility, show him respect by asking what he thinks, and he’ll open up. It was a real eye-opener.’”

More than meets the eye

According to the New York Times, he did “more for the spirit of Catalan people in 90 minutes than many politicians in years of struggle” when he inspired a 5-0 away win at Real Madrid en route to Barça’s long-awaited league title in ’74. As a coach, his playing style remains at the heart of the club’s philosophy to this day.

Ibrahimovic’s ill-fated season at Barcelona is a case in point. They spent a season telling him what to do and how to play. Football felt like school, right down to their demanding that he drive his club Audi everywhere. To prove a point, he parked his Ferrari at the training ground the following day. It caused a scene.

In those early Ajax months, only one person could make him listen. “Marco van Basten was in charge of the youth team and spent a lot of time with Zlatan,” says Endt. Ibrahimovic has admitted he was “like a little boy” around the Dutch legend, the pair frequently taking bets over how many goals the Swede would score in the next game.

Endt continues: “Van Basten used to tell him, ‘In football it’s nice to be a great technician, but at the end of each season people will count how many goals you scored; how useful you are to the team. Focus on that.’ Anyone else could talk for hours to get through to him, but just two sentences from Van Basten was enough for him to see he must change.”

Life in Amsterdam was difficult for Ibrahimovic. Cut off from his Rosengaard support network, Zlatan grew homesick. The situation was worsened by the young player spending all of his money on a brand new car, not realising he’d have to wait until the end of his first month to get paid again. The first person he met at the airport helped him out.

“We’ve known each other since our first day in Amsterdam,” says Maxwell, the PSG left-back and Ibra’s best friend in football. The pair have been team-mates at Ajax, Inter, Barcelona and PSG. “We did almost everything together,” the Brazilian tells FFT. “One day he called me, saying: ‘Maxwell, I have nothing to eat – let me stay at your house.’ He stayed with me for one month. That’s how our friendship was built.”

It’s a side that few outside Ibrahimovic’s inner circle ever get to see.

“Ours is a friendship that will remain after football, which is rare,” continues the 35-year-old defender. “He’s like a brother to me. He was a very important person in the worst moment of my life, when I lost my brother Gustavo in a car accident six months after I had moved to Ajax. I had no one with me. He was one of the first people to say kind words. We’ve always been there for each other.”

This Zlatan scarcely resembles the same person we think we know.

“That’s definitely a character he has created – a mask,” says Endt. “It’s a way to protect himself, as he likes to be this larger-than-life persona. He has always been a bit insecure.

“On the outside, Zlatan is like a guy from a movie, but inside he’s quite quiet. You just don’t see it very often. Look at his relationship with Maxwell. They are total opposites: Maxwell is like the perfect English schoolboy. Yet Ibrahimovic would often ask him, ‘How did I play today?’ He wants people to confirm his talent; to tell him that he’s doing well.”

Motivated by revenge

Loyalty to the people who stood by him during the tough times – and who helped to inspire the maniacal Zlatan pastiche that he so carefully cultivates – creates another strand to his psyche

Ibrahimovic’s relationship with football bears an interesting parallel to that of Steven Gerrard and Liverpool after the club won the 2005 Champions League Final. The Reds’ captain had just become European champion, but he nearly left Anfield a few weeks later because he needed his club’s reassuring nod that he was playing well.

The more Zlatan plays the egotistical prince, the more the wider football public listens. One of the first boasts, specifically about twisting and turning Liverpool’s Stephane Henchoz – “First I went left and he did, too; then I went right and he did, too; then I went left again and he went to buy a hot dog” – became typical of what followed.

“Do you believe in God?” he asked a nervous Carlo Ancelotti as PSG closed in on the 2012-13 Ligue 1 title, their first for 19 years. Ancelotti said he did. Ibra’s reply: “Good, so you believe in me. You can relax.”

“I don’t think he’s changed a lot,” Roberto Mancini tells FFT. “I guess he has matured, because he’s more experienced, but I don’t think he has changed character. He's still just Zlatan.”

Loyalty to the people who stood by him during the tough times – and who helped to inspire the maniacal Zlatan pastiche that he so carefully cultivates – creates another strand to his psyche, one of particular relevance to Manchester United. Revenge.

Read any page of Ibrahimovic’s autobiography and the words drip with the desire to prove people wrong. That mentality is what separates him from other supremely gifted but unmanageable talents, some of whom throw scissors at their team-mates.

He holds grudges, too, and claims he will never forgive Hasse Borg, Malmo sporting director, for securing the best deal for the club and not Ibrahimovic by selling him to Ajax

“I want people to forget me,” he said six games into his professional career in 1999, after Malmo had been relegated from the Swedish top flight. “Nobody should know I exist. Then when we’re back, I’ll strike down on the pitch like a bolt of lightning.” Promotion followed.

Ignored by Sweden’s national youth teams until he was 18, due to his anarchic anti-establishmentarianism, Zlatan is powered by revenge. He holds grudges, too, and claims he will never forgive Hasse Borg, Malmo sporting director, for securing the best deal for the club and not Ibrahimovic by selling him to Ajax. Yet it drove him to new heights.

“Soon after he arrived, he asked me how much I thought he was earning,” former Ajax defender Bergdolmo tells FFT. “I made a guess, partly based on his high transfer fee. Zlatan replied, ‘I don’t even earn half of that!’ He went straight upstairs to talk with technical director Beenhakker. Five minutes later he came back downstairs and said: ‘In four years, I’ll be the best striker in the world.’”

“I told him that the pitch was the only truth,” recalls Beenhakker now, “and that if he did well, I would be the first person to contact him. He understood it, and was fully motivated to show his qualities.”

Unafraid of confrontation

"Buy three or four players and sell the ones the crowd whistle at.” Such was Diego’s influence that his wish was president Corrado Ferlaino’s command, after Napoli struggled in the Argentine’s first season. Napoli won their first ever Serie A title two years later, sticking two fingers up at northern Italy’s traditional footballing powers.

By the time Ibrahimovic joined Juventus in 2004, few in Amsterdam were moved to shed a tear. Indeed, the club actively sought to sell him, after the striker clashed with club-mate Rafael van der Vaart in an international game against the Netherlands. Post-match, the Dutch midfielder told the press that Ibrahimovic had intentionally set out to hurt him. The pair had never got on, Zlatan being of the opinion that Ajax youth-team players had too much dressing-room influence.

“There was a meeting in which everybody gave their opinion,” recalls team manager Endt. “It was, more or less, Zlatan against everyone else. He waited until last, then he stood up and said to Rafael: ‘If you go to the press again, I’ll break both of your legs and cut off your f**king head.’

“The dressing room respected him for doing that. He wouldn’t give in easily, even if the whole world was against him. He would show his real character. It was a little awkward, yes, but it was also a great indication of Ibrahimovic’s mindset at the time. He will always believe in himself and he will never, ever give in.”

Inspired in Turin to show Ajax what they were missing, Ibrahimovic finished his first Juventus season as the club’s top scorer, with his goals firing the Old Lady to the 2004-05 Serie A title. He hit the gym and added muscle to his gangly physique. Ajax, meanwhile, finished second in the Eredivisie, 10 points behind PSV. The previous year, with Ibra their top scorer, Ajax had won the league by six points.

At Inter, Esteban Cambiasso got similar treatment to Van der Vaart.

“Ibrahimovic hates fake people,” former Nerazzurri team-mate Cesar tells FFT. “He didn’t get along with Cambiasso very well because Esteban was quite close to the board: he never defended the players and would always remain on the directors’ side.

“One day, Cambiasso received a bad pass and complained about it. Ibrahimovic lost his mind and said everything that had been building up – he called him a suck-up and told him to be quiet and shut up. Our coach, Mancini, had to get involved, but everyone was on Zlatan’s side.”

Ibrahimovic and PSV midfielder Mark van Bommel were constantly at each other’s throats as the Eredivisie heavyweights battled it out for Dutch titles

Yet Zlatan’s grudges aren’t always forever. Ibrahimovic and PSV midfielder Mark van Bommel were constantly at each other’s throats as the Eredivisie heavyweights battled it out for Dutch titles. Then came a fiery international friendly between the Netherlands and Sweden.

“At half-time, when we were walking towards the dressing rooms, Zlatan kicked a ball in my direction,” Van Bommel tells FFT. “He came up to me and said I had to watch out. I thought to myself: ‘I shouldn’t respond now, or we’ve got a problem.’” There was, however, always respect. “A few months later,” Van Bommel continues, “when I left Bayern Munich for Milan, I heard that CEO Adriano Galliani had asked Zlatan about me. Despite everything, he said, ‘I’d rather play with Van Bommel than against him.’

“I sat next to him in the dressing room and he helped me with several things, as I didn’t speak Italian when I arrived. He put me at ease in my new surroundings.”

They are now firm friends; indeed, Ibrahimovic played in Van Bommel’s testimonial match in 2013. The Dutchman even named his Rhodesian ridgeback – a pedigree of dog that is bred to kill lions in South Africa – after his former team-mate. “He’s quite a strong and tough dog, so it fits nicely,” Van Bommel laughs. “He has a good character, is very muscly and he has really good staying power, too. We wanted to give the dog a special name, and we all liked the name ‘Ibra’ a lot.”

Problems with Pep

Ibrahimovic’s individualistic approach proved anathema to Guardiola’s slow build, which could afford total freedom to only one player - Messi

On the other hand, some wounds will never heal. There is a Pep Guardiola-shaped elephant in the room here. Zlatan joined Barcelona in 2009 as the second-most expensive player in world football, but lasted just a solitary season, with the two barely talking. Those wounds reopened before September's Manchester derby, as City’s new manager criticised United’s No.9 for using his autobiography to settle some old scores.

“It was like being at school,” wrote Ibrahimovic in 2011. “Then Lionel Messi started saying things. He joined Barça when he was 13. He was brought up in that culture and doesn’t have a problem with that school crap. He went to Pep and said: ‘I don’t want to be on the right any more – I want to play in the centre.’ I ended up in the shadows. They passed through Messi. I didn’t get to play my game.”

Despite scoring in his first five Barcelona matches, Ibrahimovic’s individualistic approach proved anathema to Guardiola’s slow build, which could afford total freedom to only one player. Pep chose Messi.

“This isn’t working,” Ibra eventually huffed. “It’s as if you bought a Ferrari but you are driving it like a Fiat.”

This season, it’s inevitable that revenge will be at the forefront of the player’s mind as United attempt to outdo City.

“Together with the fact that he’s reunited with Jose Mourinho, facing Pep Guardiola will be a huge motivation for him,” says Endt, who understands Ibrahimovic’s psychology like few others. “He’s a proud guy and when someone cuts his wings like Guardiola did, he might not talk about it all the time but deep in his heart that hurt remains.”

Nothing, however, could stir the experienced striker’s fire quite like Manchester United, especially with Guardiola working on the other side of the city

There is nothing that would give Zlatan Ibrahimovic greater pleasure than getting revenge on his nemesis in the Premier League this season. Over the summer, he had offers from MLS and China, as well as interest declared by a number of European outfits. Nothing, however, could stir the experienced striker’s fire quite like Manchester United, especially with Guardiola working on the other side of the city.

Why the Premier League? To prove that his incredible strike rate of nearly a goal every other game at PSG is symptomatic more of his continued excellence than a French league that lacks quality. To prove a point to an often-sceptical English football public, who needed Ibrahimovic to score four goals – including a 30-yard overhead kick – against England in November 2012 to be convinced that he’s actually any good. To prove that he can win titles wherever he ends up. That mentality is what Mancheter United, above all else, want to tap into.

“He trains as he plays,” says Gallstad, his former youth-team coach. “He won’t go onto the United training ground to jog around and just get it done. It’s always 100 per cent. When he left the Euros in June, he didn’t go on holiday. He was intent on proving that United haven’t bought s**t, but the best. It quickly showed.”

“I think United were panicking, looked at Zlatan and saw someone who comes with an incredible title-winning record,” says David Endt. “They’re looking for instant success and he can help. He’s still very fit. I’m amazed at his physique, to keep that big frame in shape at 35. They have played the one card left to them. Even if it’s only for one year, Zlatan gives fans and players hope.”

Repeat of history

Nearly 33 and past his best, the dreadlocked Dutchman was nevertheless the most important signing in Chelsea’s modern history as a statement of the club’s intent to bring glamour and glory back to the Bridge. As player-manager, he then won the Blues’ first major trophy for 26 years and made Gianfranco Zola his first signing.

It’s exactly the same situation in which Manchester United found themselves 24 years ago.

“There are definite parallels between Zlatan and Eric Cantona,” the Frenchman’s former team-mate, Lee Sharpe, tells FFT. “Eric had this arrogance. Us youngsters were in awe of him, to be honest. He spoke way more English than he cared to let on – I once talked to him about philosophy and psychology on a night out – but he played his role very well because it made us all listen.

“Ibrahimovic is the same. He scores goals out of nothing, he scores in tight matches, and he scores in big matches when it looks like it is going to be nigh-on impossible to unlock a defence. He raises the level of play and sets the example for the team.”

Much like Cantona and Alex Ferguson, Ibrahimovic’s relationship with Red Devils manager Jose Mourinho will be vital if the Swede is to inspire an anticipated title surge. Their one season at Inter in 2008-09 confirmed a genuine bromance between the two. It’s the Portuguese’s presence at Old Trafford that convinced Zlatan.

At the beginning of this season, Mourinho announced: “When I told him that I had won titles in England, Spain and Italy, and he hadn’t, he thought: ‘Ah, I want to go there.’

“I give a lot of instruction in training. It’s difficult for me to do the same in matches, so I need guys on the pitch to read the game and understand what we want. Zlatan is going to be one of them.”

From Didier Drogba to Diego Costa at Chelsea, and now Zlatan himself, Mourinho has almost always set up his teams behind a hulking centre-forward capable of providing both power and finesse.

“He has great technique,” says Van Bommel. “He will give United a lot with his attitude. He brings goals, but as a central striker he also offers a lot of support to his team-mates, by receiving and holding up the ball. On top of that, you can deploy him in many different systems. He can also involve himself more in the game, by playing slightly deeper.”

If Ibrahimovic does drop back, it could spell danger for defences exposed to his hold-up play in tandem with the fearless attacking of English tyro Marcus Rashford.

“He can only learn from someone like Zlatan,” says Sharpe. “You need these sorts of players. Eric wasn’t a verbal leader, whereas Bryan Robson was, but Eric led by example – and I think Zlatan is exactly the same.”

Endt goes a step further: “Zlatan can be to Rashford what Marco van Basten was to him. Because of his past, he can develop young players in learning what football is all about. He’ll conduct that dressing room, and not by shouting or swearing. He’s more intelligent than people think.”

Non-league to Premier League: how on earth does it happen? FourFourTwo hears from those who've done it

What’s it like to be a big-money flop? 5 men who've been there tell FourFourTwo

Ibra, then, is the last of a dying breed of footballer: a larger-than-life character and someone to follow into battle, who inspires those around him through a mixture of self-aware egotism and an unflinching desire to be the best footballer possible.

“Apart from his football qualities, his leadership and appearance are just as valuable,” concludes Van Bommel. “When entering the field of play, Ibrahimovic can be compared with a gladiator. He challenges death and radiates immortality.”

It’s 24 years since one arrogant foreigner instilled a winning mentality in a dressing room desperate for such confident leadership. Eric Cantona turned Manchester United into a global powerhouse. Now, his natural successor must return them to that summit.

The King is dead. Long live Zlatan.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.