Long read: The rows, rage and relegation that made Antonio Conte a winner

Don’t be fooled by the Italian’s incredible first season in England – his road to the top of the Premier League has been a constant battle

Agghiacciante. It’s Italian for ‘terrifying’. Antonio Conte spits the word out twice like a panicked, ferocious caged animal.

Against the official black surroundings of Juventus and the charcoal tailoring of his jacket, his livid face appears to thrust forward even more violently. Then, when he pauses, there’s the deafening silence of a stunned, embarrassed media room. As the tirade mounts, Conte looks like he may burst into tears.

The word was destined to keep following him around like a ball and chain. For Conte, the match-fixing charges laid against him in 2012 were a Kafkaesque nightmare. The press conference was exposing his terror of losing the Juventus job on which he’d fixated for so long.

For Maurizio Crozza, it was a stand-up sketch just waiting to happen. Imagine a slightly less imposing and slightly more Italian version of Dara O Briain. During his new Friday night show, the comic launched into a parody of the agghiacciante diatribe. Mimicking Conte’s nasal Salento accent, Crozza-Conte is besieged by lawyers. They continue to pop up in every corner – even when he’s in bed with his wife. The whole sketch is rounded off as Crozza doffs his lavish wig in homage to the manager’s artificially augmented barnet.

Conte later admitted that even his other half was a huge fan of Crozza’s impersonation. Whenever he got angry, she would chant, “Agghiacciante! Agghiacciante!” back at him. All of the stress, he joked, “was making my hair transplants fall out”.

Coaching gene

Self-deprecation isn’t always on display with Conte, but it was the making of him as a manager

Self-deprecation isn’t always on display with Conte, but it was the making of him as a manager. He was 20, playing for hometown club Lecce, when he began coaching his brother’s team.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“I understood straight away that on the bench I had the kind of talent I lacked on the pitch,” he said. “As a player I could run, fight, be a threat in the box, sacrifice myself for the team, but that was it.”

Giampiero Ventrone was Juventus’s fitness trainer during Conte’s medal-laden playing career with the Bianconeri – and he believes that those deficiencies helped to form the coach.

“He was great at understanding his limits,” Ventrone explains to FourFourTwo. “To compensate, he would always apply himself to the utmost with hard, focused training. Every year he was called into question, but in the end he stayed at Juventus and became their captain. He won it all for himself with work and sweat. He took that experience into his coaching.” He also brought Ventrone, who was on Conte’s staff during several of his early managerial appointments and went by the nickname ‘the Marine’.

In 13 years as a Juventus player, Conte won a Coppa Italia, a UEFA Cup, five Serie A titles and the Champions League in 1996. Yet, in 2004 he was let go. A hangdog Conte headed to Florence to sign up for his UEFA Pro Licence at Coverciano, Italy’s sacred coaching school.

But even a year shut away in academia couldn’t drive Conte to play second fiddle to another boss. The offer came from Siena sporting director Giorgio Perinetti in July 2005. Would Conte be assistant to Luigi De Canio, the long-time worker of minor miracles at B-list clubs?

Time as a No.2

De Canio indulged Conte’s nascent mania for using video clips as a coaching tool, and sometimes allowed him take the Siena squad through parts of the previous match

Thinking it would put them off, Conte invented an elevated salary demand – but Siena didn’t blink. Conte’s self-esteem was tickled. He agreed but insisted that he wasn’t just going to be the bib-and-cone man, and would leave if offered a manager’s job.

De Canio must have felt like he was sitting on a volcano, but Conte’s ire at not being in charge rumbled mostly under the surface. “With De Canio, Antonio was extremely intelligent,” Perinetti tells FFT. “He accepted his role and grew up a lot."

Ventrone claims Conte’s charisma had stood out from an early stage. “De Canio had the honour and good fortune to have one of the three best coaches in the world for an assistant,” he says. “Conte already had very clear ideas. You could see that he was not just your average former footballer turned wannabe coach. Antonio already had his own path. He tried to impart his concept of football and it was different from De Canio’s.”

De Canio indulged Conte’s nascent mania for using video clips as a coaching tool, and sometimes allowed him take the Siena squad through parts of the previous match.

Siena’s black and white kit seemed to magnetically attract ex-Juventini like iron filings. In addition to Conte and Ventrone, Perinetti had spent time in Turin, having headed up the club’s youth system. The Siena squad featured no fewer than eight former Juventus players, such as Nicola Legrottaglie and Igor Tudor.

On the last day of April, the Old Lady visited Siena’s Artemio Franchi stadium. A win would bring Juventus the Scudetto (later annulled by the Calciopoli scandal), while Siena were playing for Serie A safety.

Inside 10 minutes Siena were 3-0 down. The home crowd turned on their ex-Juve contingent. The scoreline didn’t change, but other results meant Siena survived. In the aftermath, Siena chose not to renew De Canio’s contract and eventually released Conte as well.

Tough times at Arezzo

Conte lasted a mere three months in charge: still, time enough for an introductory dressing-room tirade, eight league games, only four points and three crucial penalty misses

By July 2006, Conte was feeling trapped – he was traipsing around IKEA with his wife Elisabetta when Arezzo sporting director Ermanno Pieroni called. Whichever ambition was the stronger, either becoming a manager or finally being able to stop staring at flat-pack furniture, Conte’s response was an instant yes.

He found a club in bits, minus the instructions and Allen keys. Arezzo had been docked six points over their involvement in the Calciopoli affair. The important players from the previous season’s Serie B play-off challenge were deserting. Even Conte himself was the second choice. In 25 years, only two Arezzo managers had ever survived more than a single campaign.

Conte lasted a mere three months in charge: still, time enough for an introductory dressing-room tirade, eight league games, only four points and three crucial penalty misses. He knew he was the fall guy, but he also knew that he was determined to fill his knowledge banks up to the brim, and embarked on a mildly farcical working holiday to Amsterdam to watch Louis van Gaal.

Conte observed one Ajax training session, although was too timid to introduce himself to the Iron Tulip. The following day turned out to be a closed session and a security guard asked Conte to leave – only after asking for his autograph.

Conte switched his sights to Italy’s amateur leagues – security guard-free and, he concluded, home to many nameless gurus of the game, full of wise nuggets to squirrel away for future reference. Or perhaps driving for mile after mile between the country’s slogging fields simply scratched his workaholic itch.

Meanwhile, after four months under an alternative manager, Arezzo were bottom of Serie B. In March they called Conte back – they were 10 points shy of safety, a task he couldn’t turn down, despite his wounded pride.

Demanding control

You can’t compromise, you just need to follow him because all of his ideas are brilliant

“Our only option is to win,” he told the press. “A draw, at this stage of the season, is just the same as a defeat. And to win we have to attack.”

As Conte writes in his autobiography, Head, heart and legs: “It was there that I brought ‘my’ 4-2-4 into being – very high wingers, mobile strikers, two midfielders and a solid back four.”

Several weeks of quasi-military training passed by without result. Sporting director Pieroni, writes Conte, “started to grumble again. During the week he would always wear that irritating expression of someone who, if it was up to him, would do things differently.”

Antonio asked a couple of his staff to drive him over to the club.

“What’s happening?”

“What’s happening is one of two things – I make all the decisions from now on, or I will leave today.”

Arezzo’s Piero Mancini was the first club president to discover what everybody now knows. As Perinetti explains: “You cannot ask Conte to not be Conte. Once you have chosen Conte then you have to keep supporting him. You can’t compromise, you just need to follow him because all of his ideas are brilliant.”

Of their last 10 league matches, Arezzo won eight and drew one. With a victory in their final game, Arezzo were set for the relegation play-off, in spite of their earlier points deduction, but a goal in injury time meant Spezia overtook them.

Conte was steeled for a campaign in Serie C1, but he couldn’t agree terms. He left assured of his genius. However, nobody called him. Less than a month later Conte ran into Perinetti, who by now had swapped Siena for Bari – a side struggling in Serie B. “If ever you’re thinking of changing managers…” said Conte.

“Antonio, you’re from Lecce. How could I have the nerve to put you forward for Bari?” Conte was annoyed. Italy’s heel-of-the-boot rivalry meant little to him. A few weeks later, after Lecce had beaten Bari 4-0 and boss Giuseppe Materazzi had resigned, Biancorossi directors began to see things the same way.

Immediate impact

When Conte picked the team up in January 2008 they were battling relegation; they ended up in 11th

At the Covo dei Saracini restaurant, Conte sat down with Perinetti and Bari’s president Vincenzo Matarrese for some dinner, just after Christmas 2007. Conte indulged his love of traditional raw fish and attacking 4-2-4 setups, hooking Vincenzo with his tactical blueprint.

Though unfazed by the appointment of the Leccese, Bari fans were not exactly excited. Only 324 of them turned up to Conte’s first game – Bari lost 3-2 having been 2-0 up.

Conte began the getting-to-know-you process with his new squad. Or as Ventrone puts it: “Better to create a deep wound that will lead to an even deeper healing. The bigger the disruption, then the better the results. When an athlete’s used to the usual standards and then someone comes along who changes them completely, the player’s life changes. At first the impact is severe – the players react badly.

“But after two or three months the situation changes. While the player’s complaining, there’s a change in him which ultimately will lead to improvement. The results arrive. The players all know that if they play well, stay fit and win games, they earn more money.”

Sure enough, by spring, Bari were notching points and playing beautifully. All that remained was derby revenge against Lecce in May, duly achieved with a 2-1 victory. Attendances by now were in excess of 15,000. When Conte picked the team up in January 2008 they were battling relegation; they ended up in 11th.

Lecce fans now had an even larger gripe to add to the memory of an over-ecstatic goal he had scored against them for Juve seven years earlier. That summer, Conte was in Spiaggiabella (‘beautiful beach’) just outside Lecce, taking part in a five-a-side memorial competition in honour of a cousin. After winning the tournament, Conte was chased back to his holiday apartment by several Lecce fans wielding clubs.

"Tactics fanatic"

Conte, increasingly sold on his buccaneering 4-2-4 setup, suggested a couple of quick wingers instead, say Arjen Robben and Theo Walcott

Back in Bari, all was harmonious. Funds were scarce, although Perinetti did what was possible to try to bring in the players that his manager had asked for. When the 2008/09 season got under way, Conte’s flying Cockerels were delighting both supporters and pundits alike in their attacking 4-2-4 line-up.

In October 2008, Conte finished university. After 10 years’ study, he graduated with maximum marks in sports science and “a suitcase of knowledge that I use every day in my work”. He wrote his thesis on the psychology of the coaches he’d played for, with a long chapter about Arrigo Sacchi, “the coach who opened my head and changed my conception of football”.

In an interview a few months after his graduation, Conte recalled arriving for Italy training with Sacchi. “I was coming from [Giovanni Trapattoni’s] Juve, which used man-marking: I felt like I had landed on the moon when I got into all of his schemes and tactical cages. [Sacchi literally used a caged pitch in training to create a perpetual football exercise in confined space.] They say that is why I turned into a tactics fanatic. I take it as a compliment.”

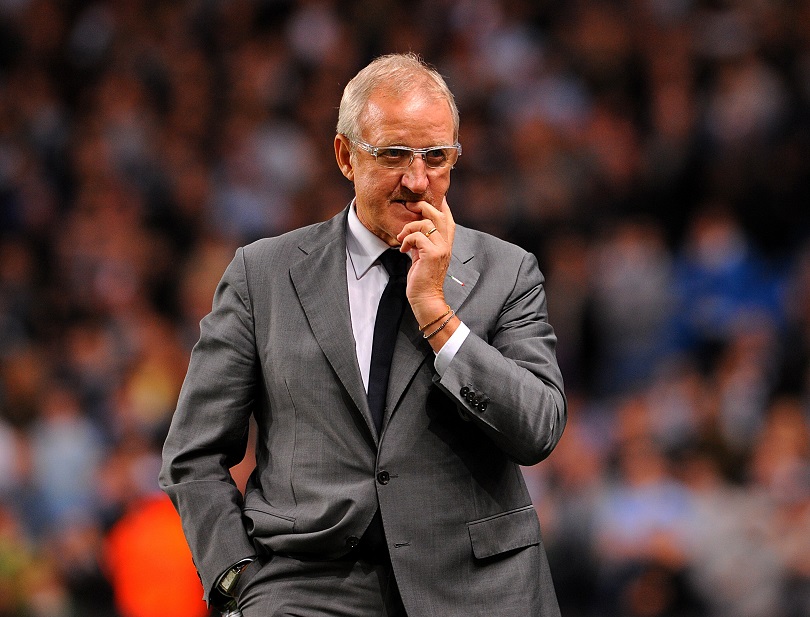

In March 2009, with Bari battling for promotion with Parma, Conte received a call from Juventus sporting director Alessio Secco. Claudio Ranieri’s Bianconeri were failing to meet expectations. Would Conte meet with him? Initially, the courtship bloomed.

The deal-breaker was Diego. Juventus were set on signing Werder Bremen’s Brazilian playmaker to try to appease their discontented support. Conte, increasingly sold on his buccaneering 4-2-4 setup, suggested a couple of quick wingers instead, say Arjen Robben and Theo Walcott. But the Diego switch was sealed.

“Diego’s more used to playing in a 4-3-1-2,” Secco explained to Conte. “When we spoke to him about your formation, he was not very convinced. It’s not how he’d prefer to play.”

“You have to make your choices,” replied Antonio, “but if a player, whoever he is, manages to influence them, then you are probably on the wrong track. If that’s the case, then I can’t be your manager.”

Promotion, parties and departure

After a mysterious delay, Matarrese suggested that the club and coach part company ‘by mutual consent’

In Bari, May 9 marks the climax of the annual Festival of St Nicholas, when the basilica disappears behind an insanely baroque facade of illuminations and the celebrations are finished off with a fireworks display. In 2009, it was also the weekend that Bari sealed promotion to Serie A, setting up a party to end all parties.

Conte was keen to take the Biancorossi into the top flight. There was a press conference announcing his new contract – which hadn’t in fact been officially signed yet. After a mysterious delay, Matarrese suggested that the club and coach part company ‘by mutual consent’. Conte agreed, having lost patience with the president’s refusal to put a formal deal in front of him. The very next day, Bari announced his successor in the form of Giampiero Ventura.

If that episode was curious, then Atalanta must have felt like falling down the rabbit hole. The club called Conte in September – they were four games into 2009/10 and without a single point. Conte swapped the heel of Italy’s boot for the top of its thigh, meeting with Atalanta’s 21-year-old president Alessandro Ruggeri at his house in Bergamo’s medieval old town beneath the Alps’ shadow.

Though Atalanta collected nine points in Conte’s first five games, something wasn’t quite right. Whether the players didn’t like doing fitness training with two enormous speakers blaring dance music on the sidelines, or whether they were still on the rebound from Gigi Delneri’s success in the previous two campaigns, there was the whiff of a veterans’ dressing-room cabal. When Conte substituted the captain and fan favourite Cristiano Doni during an away defeat by Livorno, the atmosphere soured and so too did the results.

They were beaten 2-0 at home to Napoli on January 6, 2010 and all hell broke loose. Afterwards, a mob gathered outside the Stadio Atleti Azzurri d’Italia slinging accusations: players weren’t showing enough effort, their heads were turned by other clubs, they were living the high life. Several players faced the ultras but could not calm them down.

Now they wanted Conte, and they would wait until midnight if necessary. The club convinced him to go and front up. A couple of minutes’ reasoned dialogue turned with predictable speed into cries of “Juventus s**t!” and other far less printable things regarding his family. Conte attacked back – or at least he tried to – and several policemen had to hold him back before he gave way to a minor nervous breakdown and was escorted away. He resigned almost immediately.

Horses for courses

Siena were out to win the Serie B title and Conte wanted to feel the heat at a club that would be expecting him to win every match

Part of the popular culture of calcio is Eupalla, goddess of the beautiful game. Three months with Atalanta, Conte felt, had wiped out his two bellissimo seasons with Bari. But Eupalla was gunning for him now. Perinetti had become sporting director back at Siena, freshly relegated from Serie A and now managerless.

Conte was soon back in the city of the Palio. The horse race around Siena’s piazza intrigues the Italian. Horses represent each city district, the competition is white hot and the jockeys are permitted to impede their opponents by any means. Conte admires the fierce communal will to win within each district. “In the Palio,” he explains, “there are many similarities with the harmony created within a football team.”

Siena were out to win the Serie B title and Conte wanted to feel the heat at a club that would be expecting him to win every match. The Bianconeri duly started 2010/11 with a nine-match unbeaten streak and became fixtures among the top two.

Conte’s men travelled to promotion rivals Varese for the last game before the winter break. In the days beforehand, the coach had one mantra: remember, you’re not on holiday yet. But Siena lost 1-0 and so set themselves up for the post-Christmas training camp from hell.

On Boxing Day came the yo-yo fitness tests: both a punishment and a way of choosing scapegoats. Conte spotted a hint of Christmas tum on strikers Emanuele Calaio and Reginaldo. “If you don’t want to work, get the f**k out of here and get showered!”

As Ventrone says: “Conte isn’t particularly big, but when he gets face to face with a player, he’s two metres tall.”

“He made me do the yo-yo test again the next day and it went a bit better,” Calaio told Alessandro Alciato in his book The Conte Method. “Whatever his faults may be, and he has got them, he’s by far the best coach I’ve ever had. He makes you play well, and that’s just part of his skill. He pushes you to the limit. He pulls his head down into his tank and goes his own way, dragging everything and everyone with him.

“I can only thank him – that season I produced the small wonder of 18 league goals. His reactions seemed disproportionate… but as time passed, I understood they were all integral to a precise strategy.”

An Old Lady calls

From the opening exchanges with Agnelli, Conte started to think that the meeting was more a courtesy to a Juventus legend rather than a serious interview for the job

Siena won promotion with three games to spare. Conte the coach came of age, in a city he loved. “I get shivers,” he says, remembering some of that season. He would take the team on bonding trips to the cinema, something he would have liked to have done with Juventus, “but there, to take the players to the cinema, you’d have to close all of the roads”. He encouraged the players to watch, as he did, Siena’s famous basketball side, Mens Sana – a team that had “eyes like tigers” who oozed superiority from their warm-up.

Conte made many friends in Siena; from Mens Sana’s coach to the ditty-writing Siena supporter Paolo Saracini, who would draw Conte into karaoke sessions and, bizarrely, bring him wild mushrooms for luck. At his regular watering hole, Conte never had to buy a drink.

Yet, he kept on returning to an old conviction: “If I don’t manage to coach a big team soon, it’s best that I stop.”

This time Eupalla had nothing to do with it – Antonio captured his dream job through sheer force of personality. As Juventus stuttered to a second consecutive seventh-place finish in 2010/11, the press were tipping Delneri’s sacking. But Conte’s name wasn’t in the mix of names in the sports pages. Nobody from Juventus got in touch.

Instead, Conte managed to engineer a conversation with the Old Lady’s president, Andrea Agnelli, through a mutual friend. Agnelli invited Antonio to meet with him at home.

From the opening exchanges with Agnelli, Conte started to think that the meeting was more a courtesy to a Juventus legend rather than a serious interview for the job. So he pulled his head down into his tank and forged ahead.

“Presidente, don’t be offended, but Juve are playing like a team from the provinces. In the last few years – not just this one – they’ve been giving half the pitch away to the opposition,” Conte explained.

“So, what would you do differently if you were the manager of Juventus instead?” the president posed to Conte in reply. It was a question the prospective coach would spend the next three hours answering.

“We have to introduce a new concept of football in which everybody attacks and everyone defends – like Barcelona.” Conte expounded his own philosophy and talked of giving the Juventus old guard new motivation.

Although he didn’t know it yet, by the time that he had finished speaking, Agnelli had made up his mind.

Laying the foundations

Juve endured their first dose of Conte during pre-season in the USA, when he took the squad straight from the airport to the training ground in 38-degree heat and 70% humidity

Conte admits to crying when he received the call. “The four-and-a-half hours that separated me from Turin were never-ending, but to this day it remains one of the most beautiful journeys of my life.”

The experience was never going to be so idyllic for Juve’s players. However, Conte’s manifesto for a more proactive Juventus seemed welcome, and he found assenting faces and nodding heads from Alessandro Del Piero, Gianluigi Buffon and Andrea Pirlo.

Pirlo’s agent rang. About that 4-2-4 formation. Pirlo had no qualms about Conte’s two-man midfield. Did Conte have any qualms about Pirlo being in it? He didn’t, and had faith enough to reject the signing of Gokhan Inler, who switched to Napoli.

But Swiss right-back Stephan Lichtsteiner was just what Conte was looking for. The chase for Arturo Vidal, already started by Juve, had been concluded. Sergio Aguero was too expensive. Far too expensive. Mirko Vucinic and Alessandro Matri, however, were only €15 million apiece. The 4-2-4 was falling into place.

Juve endured their first real dose of Conte at a July pre-season tournament in the USA, when he took the squad straight from the airport to their Philadelphia training ground in 38-degree heat and 70% humidity. They lost to a Sporting side modelling exactly the sort of modern European football Conte wanted from his own team. After the following training session, the next surprise was that evening’s entertainment: a screening of their training session.

So far, classic Conte. But already during pre-season, the manager was starting to doubt the fabled 4-2-4. The Bianconeri made their competitive debut at the new Juventus Stadium on September 11, 2011, beating Parma 4-1. Conte, though, was niggled by Juve’s full-backs. His 4-2-4 required great technicians, adept at ball-winning and unpredictable movement. Lichtsteiner and Paolo De Ceglie were exposed too easily.

Three at the back

The new formation clicked, and Conte the 4-2-4 evangelist had a new motto: from now on, he’d select “the clothes that best fit the players”

Juve’s pre-season transfer strategy – based around a 4-2-4 setup – was in essence an absolute mistake. Vidal and Pirlo were a poor fit but too good to drop, and Matri was not even the right front prong.

Conte’s 3-5-2 debuted in November at Napoli. Juventus went 2-0 down, but the 3-3 draw marked a turning point. The players clawed back a match they knew they would have lost in the previous season. The new formation clicked, and Conte the 4-2-4 evangelist had a new motto: from now on, he’d select “the clothes that best fit the players”.

Gazzetta dello Sport later looked back over his three scudetti and judged the first one his “real masterpiece”. Juve may have recorded Serie A’s record points tally in 2013/14, but the second two seasons only gilded the feat of engineering achieved in the first campaign.

The switch to 3-5-2 was a milestone, but in some ways it was only a tweak. The framework of high-intensity and high-pressing football remained. Modern football, as Conte called it. “Formations took over from the tactical thinking around in the age of stoppers, liberos and wingers... today, rather than formations, it’s more appropriate to talk about playing principles. Think of Vidal. Follow him in a match: you’ll find him everywhere, in defence and attack; low, medium and high speed. He regulates our playing intensity.”

Juventus’s moves were constructed in training, tested, endlessly repeated and committed to memory. Conte’s teams appeared fast; in fact, they were quick-thinking, with a split-second advantage as they already knew what to do. Juve did not have the best players, but the Bianconero machine played from memory. All components were integral: 20 Juventus players scored in Serie A in 2011/12 and only Matri posted double figures. They finished the campaign unbeaten.

Match-fixing scandal

As Antonio said in a court statement, almost the best proof of his innocence was the fact that, “by nature, I have an almost maniacal obsession with winning”

Conte achieved this automation even as Italy boss: “If you haven’t spent time with [him], you can’t completely understand it,” Antonio Candreva said to Alessandro Alciato. “Once on the pitch, everything seems easier. If an opponent counters, you’ve already got the correct solution. It’s incredible how he predicts situations and, just like that, they all come to pass in the 90 minutes.”

In the afterglow of that maiden scudetto, the match-fixing charges dropped with a heavy thunk. In late May, Conte was relaxing with his wife on a spa weekend. When the couple turned their phones on, so many messages gushed through it was clear something was wrong. They were told Conte’s apartment had been raided by police at 5am.

The Calcioscommesse (football betting) affair set off both judicial and sporting proceedings. Essentially Conte was accused of failing to report match-fixing in two games at the end of his season in charge of Siena (one which was drawn, one lost). With the exception of Conte’s accuser, midfielder Filippo Carobbio, the Siena squad supported their former manager’s version of events, remembering his meticulous preparation.

As Antonio said in a court statement, almost the best proof of his innocence was the fact that, “by nature, I have an almost maniacal obsession with winning”. Conte felt he was drowning in the absurdity of it all: “The more I struggled for justice, the less I recognised my life.”

Last May, the court of Cremona acquitted him of all charges. But as 2012/13 got under way, Conte was banned from the Juventus bench for four months. It meant preparing the matches even more minutely. The team’s internal clockwork began to function truly automatically. They purred to nine victories and a draw until Inter ended their 49-game unbeaten run in November.

The marathon was buttressed by a reduction in injuries. Ventrone confirms that Conte’s methods “are fundamental” to this. “Conte always works at match intensity, even above, so that the athletes adapt to those energy levels. If players have to give 150% in a match, in training Conte works them at 170-180%. Diet is fundamental. It’s an aspect that has been undervalued in football, whereas for Conte it’s been a pillar of his philosophy. A player who follows the right diet recovers sooner.”

Winning: the obsession

Conte was back on the bench in December, and the Old Lady led Serie A from week eight to the finish. The 2013/14 scudetto marked the first time that Juventus had won three league titles on the spin since the famousQuinquennio d’Oro(‘golden quintet’) of the 1930s.

When Conte first arrived at Juve, president Agnelli had wished him “a Ferguson-style career” – a prospect the coach appeared to relish. As much as his longevity, Conte probably envied the Scot’s status at Manchester United: Conte’s strange departure from Juventus seems to have been the result of just not getting his own way often enough – on transfers, a crammed pre-season schedule and over personality clashes with the club’s management.

The Italian press has likened Conte to a Guardiola-Mourinho hybrid, with the Spaniard’s vision of football and the Special One’s cunning. However, Conte is also a great educator. Pirlo played for him during the Indian summer of a golden career, yet declared him “absolutely the coach who’s taught me the most”. At the start of Conte’s tenure as Italy manager, he held a two-hour session in Coverciano’s main lecture theatre to school journalists about his philosophy of football.

It is said that away from the game Conte is great company – both kind and fascinating. Although that’s a bit like saying that away from megalomania, Donald Trump’s an unassuming chap. When he was at Juventus, Conte was once asked how much of his day he devoted to football.

“Do the maths,” he replied. “There are 24 hours in a day, I sleep for five, I spend three with my family, that leaves 16.” He forgot to mention he tends not to sleep well.

Additional reporting: Alberto Santi

This feature originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!