Man United must decide what they are, and where they’re going in the transfer market

The Old Trafford giants’ latest poor campaign reflects badly on a club whose recruitment strategy has become blurred. Now it’s time to put that right, writes Seb Stafford-Bloor…

With a swift denial from Mino Raiola, the tantalising prospect of Zlatan Ibrahimovic descending upon the Premier League seemed to die. No, insisted the Swede's agent, there had been no offer from Manchester United.

A shame, really. Not only is Ibrahimovic still a highly watchable athlete, but his arrival at Old Trafford would have neatly surmised what seems to be a growing problem at the club. He will be 35 before the end of the year, would offer nothing more than a short-term solution, and yet his marketability and celebrity would probably still appeal to them.

That's the nagging suspicion about United these days: while once a club who cultivated talent and constructed teams, now their aims appear to have shifted towards something more cynical and that's been in evidence for a long time. In the short years between Sir Alex Ferguson's retirement and the present day, their ability to attract premier talent has receded and been replaced by a fascination with the faux value of being spuriously linked to the unobtainable.

Team building

Would modern Manchester United ever sign comparable players now?

Maybe it's a view tinted by nostalgia and revisionism, but United used to make stars. Not just in the academy sense – though they did – but by buying players and elevating them to a different level of the game.

Ferguson may be inextricably bound to the Class of '92 and an organic sort of success, but he – and his technical staff – also seemed to employ a recruit-to-build mentality and, in part, that dynasty was built from signing good players and evolving them towards excellence.

Money was spent during that era, and it would be disingenuous not to mention Ruud van Nistelrooy, Juan Veron, Rio Ferdinand and Dwight Yorke, but underneath that top layer was usually a supporting cast who had been bought or bred to plug the gaps that the stars couldn't always fill. Players like Ronnie Johnsen and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, Jesper Blomqvist and Henning Berg; they were neither essential nor obvious, but they were identified as having the sort of situational usefulness which all successful squads tend to possess.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Maybe this point is best illustrated with a question: would modern Manchester United ever sign comparable players now? Are they interested in working their way back to the top of the game by methodically building a diverse, flexible squad, or have they resigned themselves to being willing to ride the thermals of their year-to-year spending?

What’s the big idea?

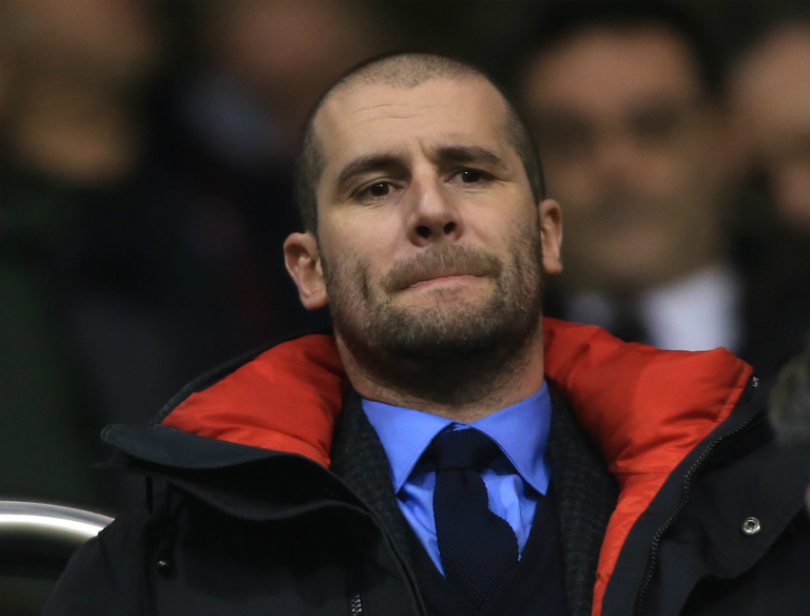

Ed Woodward is often accused of being incapable and is commonly portrayed as a bumbling negotiator who hesitates at the critical moment, but he's possibly more a reflection of his employer's intentions – is, for instance, his brief to create a successful football team, or just to grow the club's brand using the football team as a primary tool?

One hand feeds the other, of course, and there is a degree of co-dependency, but United are an example of what can happen when ratios begin to shift and sporting ambition is diluted by commercial interest and ambiguous politics.

It's all relative: they would like to win Premier League titles and European Cups, but they perhaps don't crave it in the same way that they once did – the singular, laser-beam focus which used to exist has been replaced by something far less intense. Once up a time, this club hated to lose – loathed it – now they're more accepting, just as long as it comes with compensatory revenue and a few tyre partnerships.

In relative terms, there's nothing really wrong with that. Up and down the country, both covertly and brazenly, other clubs are behaving in exactly the same way – and, in United's defence, they at least have designs on growth rather than just cynical stasis.

Signing strategies

There are still consequences to that, though, and diluted recruitment is one of them. Loyalists will claim that the signing of Anthony Martial for such an extravagant fee represented dedication to on-pitch improvement, and that the additions of Luke Shaw and Morgan Schneiderlin were evidence of the club's intent to cure first-team weaknesses with players who would improve over time.

Maybe, but more generally there's an absence of any distinct pattern to these arrivals. Some seem to suit the purpose of their manager and appear to be signed at his behest, others are just packaged and presented to him – signed almost for the sake of making a signing.

That lack of clarity is very troubling, especially given that United's transfer processes are far more opaque than any of their nearest rivals'. At Manchester City, Txiki Begiristain and Ferran Soriano control recruitment, Chelsea have long-term technical director Michael Emenalo, and Arsene Wenger has almost complete autonomy at Arsenal. Even at a smaller, upwardly mobile clubs like Tottenham and Southampton, the separation of powers is far clearer.

In February of this year, Woodward was asked to explain his failure to match spending with progress and, using Leicester as a comparison, asked why the club were unable to extract true value from the market.

"Some players are bought by other clubs with an eye to them developing into something special in a few years’ time,” he said. “Whereas there’s a bit more pressure on some of the other clubs to bring in players who are going to be hitting the ground running and top players verging on world class almost immediately. So there is a slightly different market in which people are buying.”

In a sense, he was right – there is a pressure to succeed and supporter and investor patience is at an all-time low. Though a very plausible explanation, the rumours about the club's scouting department – which supposedly had one full-time employee – and the root-and-branch modernisation which was reported by the Daily Mail's Charles Sale in April – betrayed that part of United's infrastructure for what it was: a resource which had been neglected and a department which was considered to have a minor role in the achievement of modern objectives.

Where you want to be

It casts United as the kind of club who don't take on-pitch achievement as seriously as they should

Buying players for value is difficult, but it's much harder without a proper commitment to talent identification, or without the forensic systems most top clubs now use to perform detailed analysis.

That an appetite for reform exists is encouraging, of course, but that this has evidently been low on the agenda for some time is deeply concerning.

It casts United as the kind of club who don't take on-pitch achievement as seriously as they should, and who are only now appearing to because their Champions League participation – and subsequent revenue streams – have come under continual threat.

They are a club who want to hold what they have in a sporting sense, rather than one which is determined to return to the vanguard of the game. Maybe there are individuals within the organisation who stray from that party line – Woodward himself would probably dearly love to be associated with success – but the consensus only appears to be driving towards corporate improvement rather than a more traditional football excellence.

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.