Marseille vs PSG: France's bitter and violent north-south divide laid bare

The relatively recent emergence of the OM-PSG fixture hasn't stopped it becoming the most violent clash of the year, as Graham Berger discovered for the June 2003 FourFourTwo magazine...

Midway through Sunday afternoon, the atmosphere at the Cafe de l’OM is heating up. Again the chant goes up, reverberating around this small brasserie, situated on the banks of Marseille’s Old Port. “Luis, we’re going kill you,” the Marseille fans spit, “and your whore of a mother!”

Paris Saint-Germain coach Luis Fernandez is not, it is safe to say, the most popular man in these parts. A former PSG player, it was his response to his team’s winning goal in a recent cup match against Olympique Marseille – running on to the Parc des Princes pitch and performing an elaborate salsa dance – that really continued his position as a figure of hate for OM’s fanatical support.

“What Fernandez did was a disgrace,” explains a small bespectacled man with blue-and-white dyed hair. “He spent the entire game insulting our players, then danced like a deranged idiot in front of our dugout and our supporters.” The pot-bellied Marseillais looks me in the eye. “If he tries anything like that tonight,” he warns, “I swear he will be killed.”

Southern pride

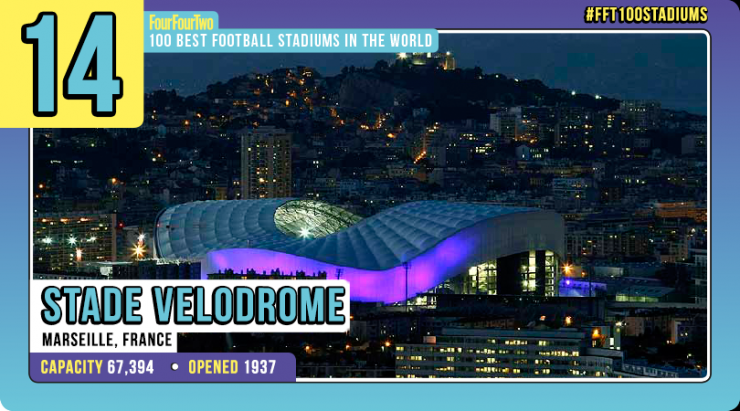

It’s an hour before kick-off and the impressive Stade Velodrome is already packed close to its 60,000 capacity. Away in the corner, the travelling Parisians are making their presence felt, firing a volley of red flares over the protective netting and onto the raging Marseille fans. Hundreds of Marseillais in the Virage Noni respond by surging towards the metal fence that separates them from the boisterous PSG fans.

The home crowd’s mood becomes blacker when stewards insist on removing their enormous banner running the length of the Virage Sud and reading: Luis, ta place est à l’asile (Luis, you belong in a mental home).

As a larger security presence is urgently radioed in, it seems only a matter of time before war breaks out. Or rather civil war. This weekend has been built up as the big one for the neglected French city of Marseille; the day when, for once, the nation’s attention will be fixed not on Paris but on the South.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Last night, local boxer Mehdi Sahnoune beat Bruno Girard to win the WBA light heavyweight title in Marseille’ s Palais des Sports before whipping the fans into a frenzy by declaring: “I’ve done my part, now let’s get behind OM tomorrow and show the rest of France what Marseille is all about!”

As a larger security presence is urgently radioed in, it seems only a matter of time before war breaks out

The city’s footballers go into France’s ‘match of the year’ as clear favourites. Joint top of the league, they have not lost at home for 15 months and boast an unbeaten record against arch-rivals PSG at the Stade Velodrome that stretches back 15 years.

PSG, in contrast, are a club in disarray. Booed by their own fans throughout the first half of their previous game against Troyes, they are experiencing another one of their seasons of underachievement. Few give Luis Fernandez and his team a hope of returning from the Velodrome with their pride intact.

Pivotal point

This is Marseille’s big chance and not just to put one over their haughty Parisian rivals. The previous night, co-leaders Monaco lost to Bordeaux. A win, or even a draw, and Marseille will be top.

It's Kylie Minogue's first ever football match. Two Marseille fans drop their trousers and moon up towards her

As the PSG players come out to warm up, the stadium explodes into a chorus of whistles, whistles that continue, albeit with a different tone, when Kylie Minogue is spotted lowering her coveted derriere onto a seat in the main stand.

This, it later emerges, is the Aussie singer’s first ever football match. And she must be wondering what she has let herself in for when two Marseille fans drop their trousers and moon up towards her, but, flanked by her actor boyfriend Olivier Martinez and former Marseille hard man Basile Boli, she probably feels safer than most in the stadium.

Just before kick-off, Fernandez emerges from the tunnel and makes for the dugout as the noise is cranked up another level. With three police bodyguards glued to his sides, each clutching a large umbrella, the coach makes his way along the touchline unharmed as objects rain down from the stands, bouncing off the makeshift shields.

The public address system bangs out that old footy favourite We Will Rock You, the two teams emerge and the four stands of the Velodrome turn into a sea of blue and white. The people of Marseille are ready; ready to enjoy their biggest party since OM won the European Cup in 1993.

Recent history

The rivalry between Paris Saint-Germain and Olympique de Marseille did not begin until the late 1980s. Before then PSG, who were only founded in 1970, rarely had a team capable of matching Marseille, traditionally a giant of the French game.

Formed in 1899, Marseille have been competing for trophies for most of their history and, for the first 87 years at least, were more concerned about games against Saint-Etienne or Bordeaux than trips to the capital.

Nevertheless, the potential for a North vs South rivalry was always there and when PSG claimed their first championship under Gerard Houllier in 1986, it finally emerged.

Under the surface there had always been an antagonism between people from Provence and Parisians

“Under the surface there had always been an antagonism between people from Provence and Parisians,” explains Laurent Perrin, football writer for Le Parisien newspaper.

“In France everything is centralised around the capital much more so than in other countries and the people of Marseille don’t like it. Football was the one thing that the Marseillais had over the Parisians, so when PSG started to win things, it didn’t go down well in the south.”

Shortly after PSG’s title success, two things happened that would shape the rivalry for years to come. First, Bernard Tapie, a socialist politician and adviser to the French president Francois Mitterand, was elected president of Olympique de Marseille. Second, Canal Plus, the biggest pay television station in France, bought PSG.

NEXT: Tapie vs Paris

Tapie vs Paris

Tapie came from a humble, working-class background. Despite growing up in a suburb of Paris, he developed a strong dislike for the city’s premier football team. A distinguished entrepreneur, Tapie believed that you should have to work hard to achieve your goals, as he himself had done, and could not stand the fact that PSG had become a big club virtually overnight following the arrival of Canal Plus.

PSG were the nouveau riche. Tapie hated them for that. He thought that, unlike Marseille, PSG had not earned the right to be one of France's biggest clubs

“PSG were the nouveau riche," says Perrin. “Tapie hated them for that. He thought that, unlike Marseille, PSG had not earned the right to be one of France's biggest clubs.”

Already one of the most powerful and popular men in France, the charismatic and smooth-talking Tapie quickly became a figure of worship in Marseille. He led a campaign against National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen and raised the profile of Olympique de Marseille to unprecedented levels.

Yet the real reason the people of Marseille took Tapie in their hearts was because he was one of them; he talked like them, he dressed like them and, above all, he harboured a strong resentment of PSG – just like them.

Tapie had this amazing presence. When he walked into the room everyone would fall silent. He loved nothing more than going back to Paris and winning. And he made that clear to us

Former England international Chris Waddle played for Marseille under Tapie between 1989 and 1992, and recalls how the president used to come into the dressing room before PSG matches to give the players a pep talk.

“He had this amazing presence,” explains Waddle, in hushed tones. “When he walked into the room everyone would fall silent. He was like a headmaster and we listened to every word he had to say. The strange thing is Bernard was a Parisian, but he loved nothing more than going back to Paris and winning. And he made that clear to us.”

He also made it clear to the French public. In the days leading up to PSG-Marseille games Tapie would go on countless television and radio shows talking up his team and winding up the Parisians. By the time the game arrived, the hype would be so great that the whole country tuned in to watch.

“Tapie knew exactly what he was doing,” claims Perrin. “By turning PSG-Marseille into this big spectacle, he was looking after the interests of his club. So long as it is the biggest game in France, PSG and Marseille will be the biggest clubs in France. Now every time they play, the stadium sells out, the TV audiences are huge it is just one big advert for the two clubs.”

Tensions building

The hype may have been a clever marketing tool, but it also heightened tensions between the two sets of supporters. Reports of fan violence became more frequent in the early-'90s as rivalry turned into downright hatred.

Even the players were not safe, as Waddle discovered on the team bus heading for the Parc des Princes. “I was sitting on the front seat next to the driver, as always,” recalls the man nicknamed le dribbleur fou (the crazy dribbler) by his adoring Marseille public.

We were driving along when suddenly this Parisian jumped out in front of us. The next thing I knew there was a brick hurtling towards my head

“We were driving along when suddenly this Parisian jumped out in front of us. The driver jammed on the brakes and the next thing I knew there was a brick hurtling towards my head. Luckily, it got wedged in the windscreen, otherwise it would have hit me right between the eyes.”

In fact, at that time, the Parisians’ anger was fuelled as much by Tapie’s snide remarks as by the enormous success Marseille were enjoying on the pitch. With a team packed with internationals like Jean-Pierre Papin, Boli, Alen Boksic, Dragan Stojkovic, Waddle and Enzo Francescoli, Marseille were enjoying the most successful period in their history, winning five successive French titles between 1989 and 1993 and reaching two European Cup finals.

In the second in 1993, they defeated AC Milan 1-0 to become the only French club to lift the trophy.

Tapie was later found guilty of match fixing and sentenced to seven months in prison for corruption, while Marseille were denied the honour of defending their European crown and banished to the Ligue 2.

It signalled the end of a glorious era but by that time -as far as the PSG supporters were concerned the damage had already been done. Tapie and Marseille had gone too far.

Flash point

Nicolas Roulande is a member of PSG’s longest standing supporters club, the Boulogne Boys. Founded in 1985, they sit in the Boulogne end of the Parc des Princes (hence the name) and are renowned for containing some of France’s most violent supporters.

Nicolas, I am assured, is not one of them. Certainly, with his wavy black hair, friendly smile and big brown eyes, he looks nothing like your stereotypical hooligan, but having travelled home and away with the Boulogne Boys from a young age, Nicolas, now 23, is not short of tales to tell.

Asked to recount the first time there were serious clashes between PSG and Marseille supporters, those big brown eyes light up. “It started in 1993, soon after Marseille won the European Cup,” he says with an air of excitement. “We had had enough, enough of Tapie and enough of the Marseillais crowing about their European Cup win.

It was only the madmen who went. I was there with my Dad, my Dad’s friend and a baseball bat

“There were 250 of us travelling down on the bus for the league match at the Velodrome. It wasn’t many but you have to realise, it was only the madmen who went. I was there with my Dad, my Dad’s friend and a baseball bat.”

A baseball bat? Nicolas was, after all, just 13 at the time. He smiles. “There wasn’t really any security around the stadium back then, and anyway, that day everybody came prepared.

“As soon as we got in, it was total carnage. We threw whatever we could get our hands on – seats, flares, everything. I don’t think there was a single Parisian there who didn’t throw something. The fighting went on for most of the game until eventually the police got their act together and we were led out of the ground with 15 minutes remaining. There were quite a few casualties.”

Ever since, matches between PSG and Marseille have attracted violence. In the return game later that season more supporters were injured as this time the Marseille fans attacked, smashing up the toilets in the Parc des Princes and using the debris as missiles to hurl at the home fans.

NEXT: Patriotism and racism

The English disease?

The violence got worse through the 1990s until the authorities belatedly accepted the problem of football hooliganism in France had become all too real.

According to Nicolas, the French have the English to thank for the emergence of match-day violence in France. “Hooliganism arrived in Paris the day England played France at the Parc des Princes in 1985,” he claims.

There was fighting in the stands the whole game, stuff was being thrown, they even invaded the pitch. We’d never seen anything like it. The only memories I have of that day is of the English fighting

“There was fighting in the stands the whole game, stuff was being thrown, they even invaded the pitch. We’d never seen anything like it. I don’t even remember the game – the only memories I have of that day is of the English fighting.”

Soon after that ‘friendly’, PSG began to attract right-wing extremists to their matches and football in Paris became synonymous with violence. “The skinheads decided that they would start to hold their meetings in the Boulogne end,” Nicolas goes on.

“Back then it only cost 10 francs to get in because PSG hardly had any supporters. None of them were interested in the football, it was just a convenient place to meet and discuss plans for their next fight.”

Even today the Boulogne end of the Parc des Princes contains a sizeable fascist contingent, and remains a no-go zone for non-white supporters. “You never ever see a coloured person in the Boulogne. Never,” confirms Nicolas.

A large proportion of the PSG fans remain fiercely nationalistic, showing off their patriotism by decorating the Parc des Princes with the French Tricolore and, on special occasions, a giant banner of the Arc de Triomphe.

The main reason we hate Marseille is because they are a club of foreigners full of blacks, Arabs and whatever else. And we’re proud of our country. What’s wrong with that?

In Marseille, the situation is very different. The city’s population is made up largely of Spanish, Italian and North African immigrants and while the National Front attracts significant support in the region, the football club, if anything, brings Marseille’s multi-racial community closer together.

The contrasting backgrounds of PSG and Marseille supporters provide an additional source of antagonism. “The main reason we hate Marseille is because they are a club of foreigners full of blacks, Arabs and whatever else,” says Nicolas spitefully.

Sensing an accusation of racism is on its way, he goes on “...and we’re proud of our country. What’s wrong with that?” he demands.

“The people of Marseille apparently liberated Paris during the French revolution, yet now they don't give a damn about France. These days they come here for two reasons – to find trouble and to spit on the capital.”

Samba sorcery

“It wasn’t supposed to be like this,” mumbles a distraught Claude Martin, a journalist for La Marseillaise newspaper, as he watches Jerome Leroy make it 3-0 to PSG.

The reason for the scoreline is simple: Ronaldinho. The Brazilian has been an enigma during his two seasons in the French capital, rarely producing the form that embarrassed England in the World Cup and frequently falling out with Luis Fernandez.

But tonight, two years of childish antics and inconsistency are forgotten as the 23-year-old turns in a performance that will win him a place in the hearts of PSG fans forever.

By half-time it should be all over, as the Brazilian makes a mockery of France’s meanest defence, bobbing in and out of challenges from Frank Leboeuf and Daniel van Buyten and laying on chance after chance for strike-partner Bartholomew Ogbeche.

But at the interval, PSG only lead 1-0 (courtesy of Leroy’s 26th-minute strike). After his series of misses, the inexperienced Nigerian is substituted and it is left to Ronaldinho to show him how it is done.

Intercepting a Leboeuf pass on halfway, the Brazilian sprints confidently towards the Marseille penalty area, glances up and flips the ball expertly over goalkeeper Vedran Runie. 2-0. Cue frenzied celebration among the 800 travelling supporters, but the best is still to come.

Eight minutes remain when Ronaldinho, by this time loving every second, picks up play 10 yards inside his own half. Two step overs are followed by another powerful surge that leaves Leboeuf chasing Ronaldinho's bounding locks once more.

This time the PSG ace coolly rounds Runje, drags the ball back inside the defender on the line and nonchalantly rolls it goalwards for team-mate Leroy to score his second of the night.

Stunned silence fills the Velodrome air as hundreds of home supporters make for the exits. Yet the overriding sentiment is not one of disappointment or anger, but disbelief. So confident of victory were the Marseille fans in the upper tier of the Virage Sud (who go by the name of ‘the South Winners’) that they have brought along their own sound system and firework display.

With full-time approaching, they decide to go ahead with the party regardless of the score, so the final minutes are played out in a surreal atmosphere as an impressive array of fireworks light up the sky and some less impressive hardcore techno vibrates around the semi-filled stands.

There is no trouble. There is barely a chance of it. The PSG buses are stopped by police 150km north of Marseille and made to wait for over an hour while everyone is searched. Then they are escorted to the ground and the fans ushered straight in. After the game, the jubilant PSG supporters are held inside for another 90 minutes before beginning the long journey back to Paris.

But there is more to it than carefully co-ordinated policing, as Le Parisen's Perrin is only too well aware. “This Saturday, PSG play away to Martigues in the cup,” he points out.

“Martigues is very close to Marseille, they have a tiny ground with no security. The word is that the PSG and Marseille ultras did not even try to arrange anything at the Velodrome because they knew it would be too difficult. Wait and see what happens in Martigues.”

The following Saturday, three men from Southern France are arrested attempting to enter the away section of the Martigues stadium with a homemade bomb. The rivalry, it seems, is very much alive.

This article appeared in the June 2003 issue of FourFourTwo magazine – subscribe!