Meet the hardest player ever… and you’ve probably never heard of him

He may not be as recognisable as Chopper Harris, Billy Bremner or Vinnie Jones, but Roy McDonough was a tough nut like no other. After all, you don’t get a record 13 red cards unless you like a scrap…

There’s a long pause as Roy McDonough considers the question. “How would I cope in today’s game?” ponders the former Walsall, Colchester, Southend, Exeter and Cambridge hitman. “I wouldn’t even make it past the warm-up.”

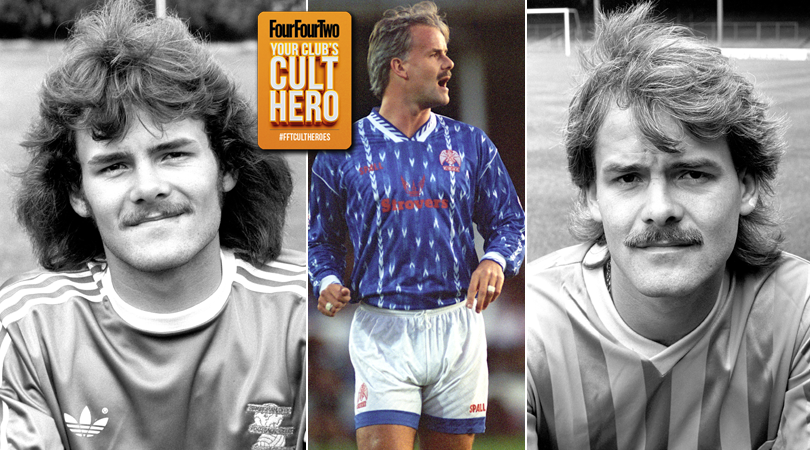

‘Donut’ received 13 red cards in his professional career – a number matched only by former Wigan and Leicester defender Steve Walsh – and 22 in total; hence the title of his 2012 autobiography, Red Card Roy.

But it’s the book’s subtitle that paints a more complete picture: Sex, Booze and Early Baths: The Life of Britain’s Wildest-Ever Footballer. While McDonough’s familiarity with the referee’s notebook is well documented, and his womanising legendary, it was the drinking that makes the mind boggle most.

At the height of his boozing, McDonough would drink 70 pints a week – 24 in a single session; 12 the night before a game. His party trick was to down a pint in seven seconds while standing on his head. “I saw him do it on a moving train once,” friend and former team-mate Perry Groves tells FFT. “Very impressive.”

At the height of his boozing, McDonough would drink 70 pints a week – 24 in a single session; 12 the night before a game. His party trick was to down a pint in seven seconds while standing on his head

Behind the bravado and boorish behaviour, though, McDonough was, in his own words, “a gentle soul who just needed an arm round the shoulder”. A man who was only drawn into a world of punch-ups, piss-ups and leg-overs by “frustration and insecurity”. A player whose career was blighted by bad decisions, touched by tragedy and riddled with regret.

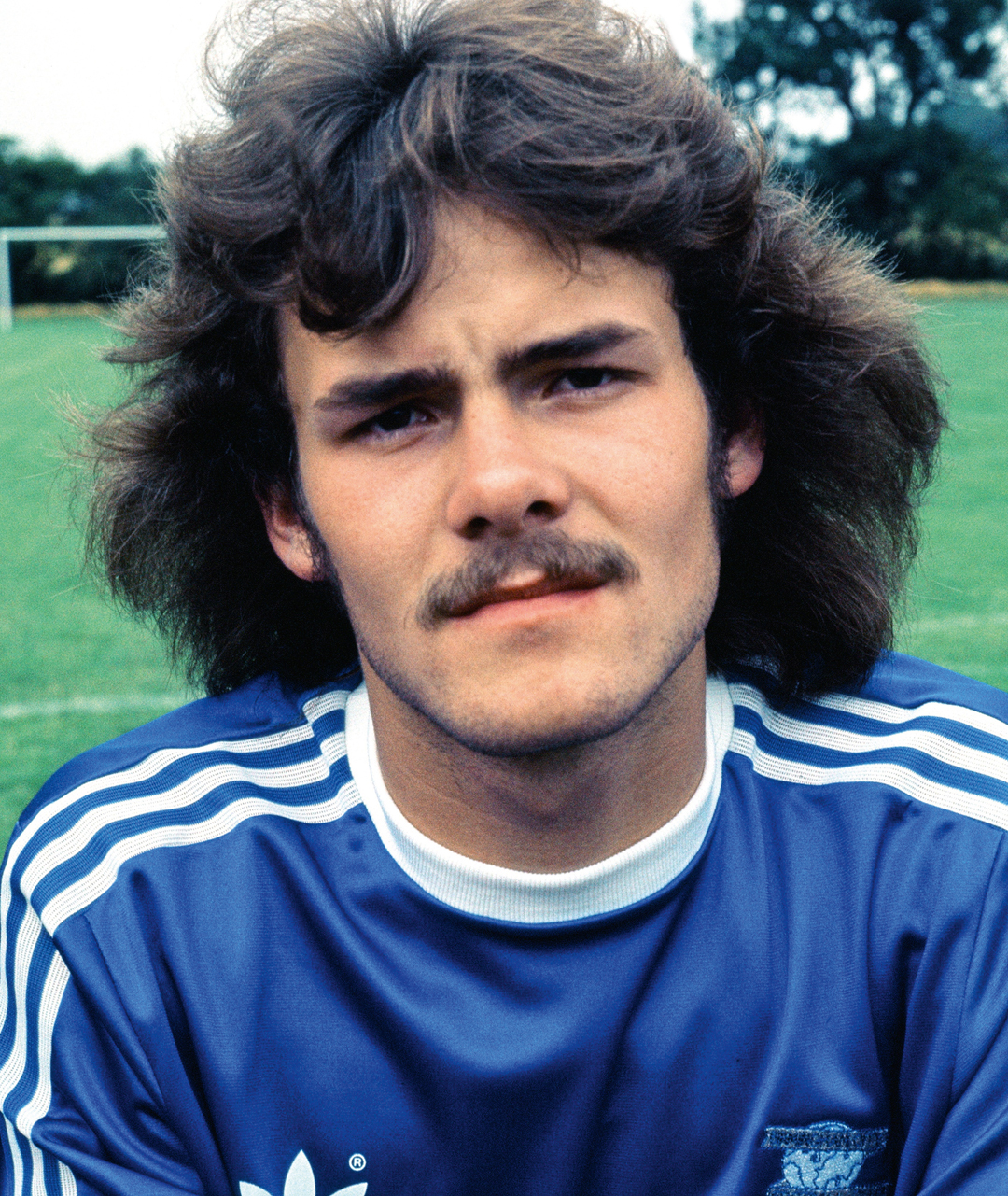

As with many things in McDonough’s life, even the macho moustache favoured by the hardmen of the day was rooted in insecurity, grown as a teenager to cover up a blemish on his top lip. “He was,” says Groves, “a Rottweiler on the pitch but a poodle off it.” So where did it all go wrong?

RECOMMENDED Revealed! YOUR club's Cult Hero – as voted for by the fans

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Broken at Birmingham

What the f**k was I doing, leaving Birmingham for Walsall?” Within a week, Francis and Bertschin both got serious injuries, which would have given me my chance

Although McDonough received his marching orders for the first time aged 16, when he lifted up a referee by the throat during a Birmingham Schools’ Cup final, he simply put it down to ‘John McEnroe Syndrome’, believing his volatile temper would not get in the way of his undoubted talent.

Born and bred in Solihull in the West Midlands, he had all the makings of a top centre-forward. “The football world was his oyster,” Ian Atkins, a friend since childhood who had a 30-year career as player and manager, tells FFT. “He was seriously quick, six foot plus, and could lead the line. What would a striker like that be worth in today’s game?”

Rejected by Aston Villa as a schoolboy, McDonough joined rivals Birmingham City. A dedicated, teetotal young pro, he made his first-team debut in 1977 aged just 18, partnering Blues and England star Trevor Francis, whose boots he had been cleaning as an apprentice just months earlier.

McDonough scored his first professional goal in his second appearance, a headed equaliser at Loftus Road on the last day of the season. On the coach trip home, he got drunk for the first time in his life.

“Next season,” he vowed, “I’ll keep my place and become a top-flight star.” In fact, he would never play in the First Division again.

That summer, England’s World Cup-winning manager Sir Alf Ramsey joined the Birmingham board and immediately recommended the signing of England U21 striker Keith Bertschin. McDonough was back in the reserves. The situation didn’t improve when Ramsey moved into the St Andrew’s hot seat, even though he told Roy he was “a jolly good player”. When Ramsey’s successor, Jim Smith – “the best manager I ever played for” – told McDonough he was free to speak to other clubs, the youngster was devastated.

Third Division Walsall seemed an unlikely place to resurrect a promising career, but McDonough wanted to stay close to home, believing it wouldn’t be long before he was back up the ladder. It was a decision he soon regretted. “What the f**k was I doing, leaving Birmingham for Walsall?” he says. “Within a week, Francis and Bertschin both got serious injuries, which would have given me my chance, but it was too late.”

“When he left Birmingham things started to go wrong,” believes Atkins. With the Saddlers struggling and their new striker misfiring, the boo-boys had an easy target. During one game, McDonough had to be restrained from jumping into the crowd Cantona-style after a “volley of insults” from one “mouthy pr**k”.

Walsall were relegated, with McDonough’s spell up front memorable only for a first professional red card and a run-in with legendary Liverpool hardman Tommy Smith, then at Wrexham. “The ball went down the touchline and he was favourite to get there,” says McDonough, who recalls “clattering straight through” the Kop enforcer and “dumping him in a pile of snow”.

Like football’s answer to Forrest Gump, McDonough seemed fated to cross paths with some of the most famous figures of his generation – and Smith was the first of many nutjobs. Having been at Birmingham with Mark Dennis (12 red cards), Pat Van Den Hauwe (“a scrapper”) and Kenny Burns (“a law unto himself”), ‘Big Roy’ went on to lock horns with Mick McCarthy (“a gobs**te”), Terry ‘Animal’ Hurlock (“the first one in if a row kicked off”), John Fashanu (“lanky plank”), Steve Walsh (“hard but fair”), Sam Allardyce (“the biggest head I’ve ever seen”), Tony Pulis (“a little f**king squirt”) and Vinnie Jones (“a bully”).

Although Walsall bounced back up at the first attempt, McDonough was becoming more pre-occupied with scoring off the pitch than on it. True to form, he signed off by picking up a dose of gonorrhea on an end-of-season trip to Magaluf. His reputation as a troublemaker firmly established, Walsall offered him a new contract but on reduced terms. “Stick it up your arse!” he replied.

“Geoff Hurst was a clown”

Looking back, I wish I could have sat down with a psychologist, because I’d lost all my self-respect and love for the game. From that point on I became a big drinker and womaniser

Arriving at Stamford Bridge in September 1980, McDonough reckoned he was back in the big time, and ready to fire Chelsea’s return to the top flight. But he reckoned without his new gaffer, who, like Ramsey, was a hero of England’s 1966 World Cup win. “Chelsea was like a circus,” explains McDonough, “and Geoff Hurst was a clown. The worst manager I ever played under.”

Not that he saw the England legend much. According to McDonough, Hurst didn’t see him play before Chelsea signed him and never came to watch him in the reserves, where McDonough spent most of the next 18 months.

In his one first-team appearance, he was thrown in at centre-back to perform a man-marking job on Dutch World Cup star Rob Rensenbrink, who was one of a handful of stars appearing for FC Dordrecht in a mid-season friendly. “He barely broke sweat,” recalls McDonough. “Johan Cruyff played behind the front two, so I had to occasionally abandon Rensenbrink to put a challenge in. I was chuffed I managed to tackle Cruyff twice. I missed him the other 39 times.”

Chelsea won 4-2, but Hurst blamed McDonough for the Blues’ “bad 10 minutes”. Homesick, lodging with a married couple on a council estate near Heathrow Airport and clearly not in the manager’s plans, the 22-year-old reached the pivotal moment in his career. “Chelsea broke my heart,” he says. “Looking back, I wish I could have sat down with a psychologist, because I’d lost all my self-respect and love for the game. From that point on I became a big drinker and womaniser. Bollocks to it, I thought, I’m just gonna party.”

Desperate to end his Chelsea nightmare, McDonough joined the “nearest club that showed interest”. “What division are we in?” he asked on arrival at third-tier Colchester United in 1981. Not that he cared. Birds and booze were now McDonough’s priority. One session involving some of the stars of nearby Ipswich, then at the height of their success under Bobby Robson, ended with England defender Terry Butcher hopping naked around the bar with a hand over one eye – a forfeit known as ‘The Pirate’. “Terry was a good lad but he couldn’t keep up with us,” says McDonough. “We were f**king monsters.”

Yet tragedy soon struck. McDonough’s strike partner, David Lyons, with whom he had been drinking only hours earlier, took his own life three days after his 26th birthday, the victim of mounting depression that had gone all but undetected. McDonough wore his friend’s No.9 shirt against Tranmere two days later, celebrating wildly when he scored after just 45 seconds. He soon reverted to type, getting sent off in a reserve team game for giving a former team-mate “a right hook”. After leaving Colchester, spells at Southend, Exeter and Cambridge followed. Each lasted less than a season; two ended in relegation.

Moyes? How could a giant ginger Jock from Glasgow Celtic play with absolutely zero aggression, putting all his energies into bleating on about Jesus instead?

His first stint beside the Essex seaside concluded when he punched assistant manager Colin Harper in the face during a game of five-a-side in the Roots Hall car park. He then turned down George Graham’s Millwall (“another huge mistake; the fans would have loved me there”) to play for Exeter, managed by former England captain Gerry Francis. After a 10-month, Stella-fuelled party in the West Country, it was back to East Anglia and an uneasy alliance with the Abbey Stadium’s three-man ‘God Squad’, including David Moyes. “How could a giant ginger Jock from Glasgow Celtic play with absolutely zero aggression, putting all his energies into bleating on about Jesus instead?” wondered McDonough.

Cambridge was also the scene of the most extraordinary of many drink-driving episodes. So plastered after the club’s Christmas night out that he was unable to feed coins into the parking meter, McDonough put his foot to the floor and hurdled the 10-inch ramp guarding the exit “like the Dukes of Hazzard”.

His final game for the U’s was a similar blur: McDonough was “so messed up” that as he looked at the ground he saw “two distorted balls” at his feet.

Pulis and the flying kick

The Newport County midfielder had ‘got right under’ McDonough’s skin during a previous encounter and he was looking for his opportunity to ‘even things up’

“You all right, big fella?” enquired Southend manager Bobby Moore. “You won’t let me down, will you?”

“Course not, boss,” McDonough replied. Seven minutes later, he was heading back up the tunnel for an early bath, the first of seven during his second spell with the Shrimpers, and one of few he regrets. McDonough finally had a manager he wanted to play for, was paying (a little) more attention to diet and fitness and had stopped living in the past, now drinking purely for social reasons and not to numb the pain of his unfulfilled promise.

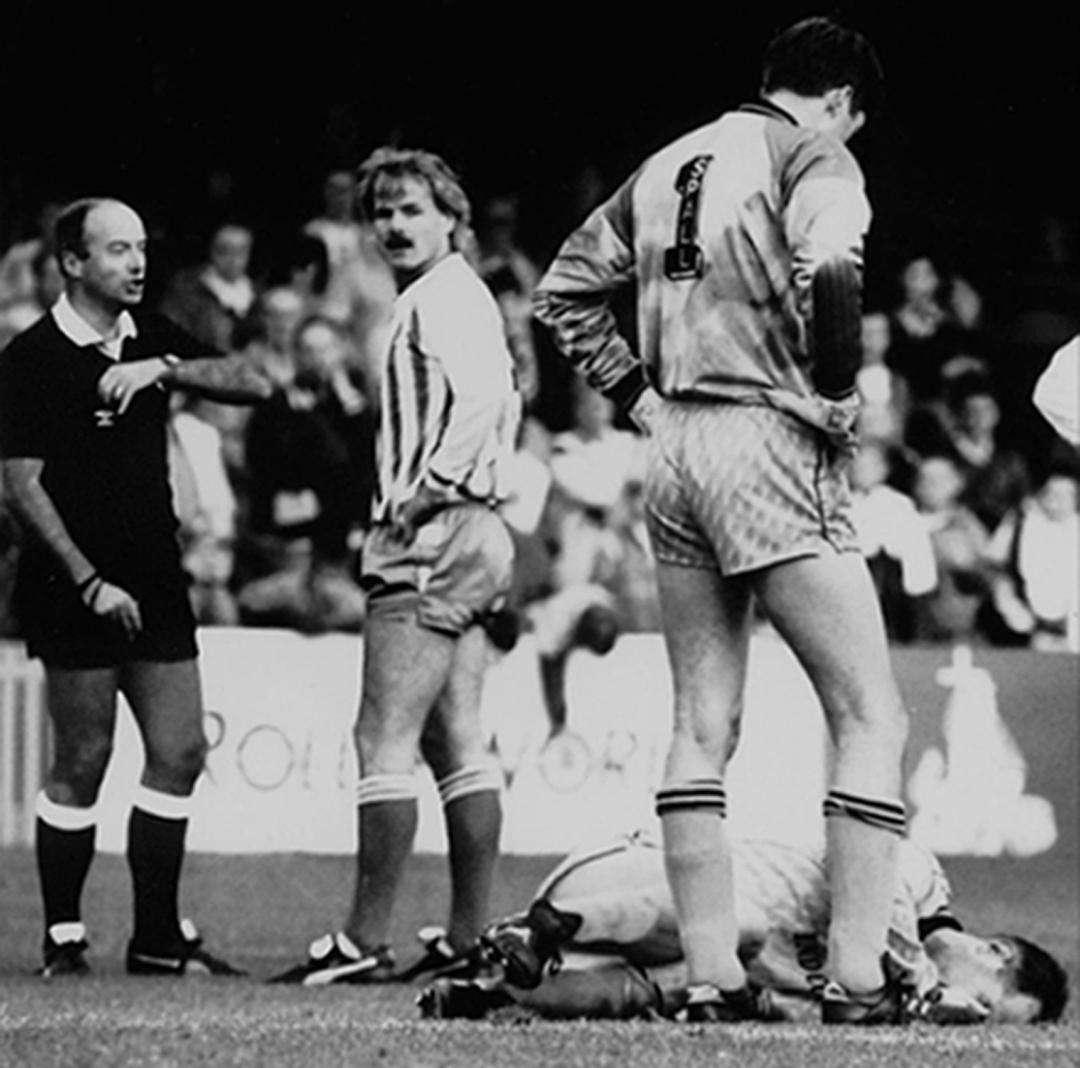

But England’s World Cup-winning captain could see the look in his targetman’s eyes as he lined up opposite Tony Pulis ahead of an FA Cup tie. The Newport County midfielder had “got right under” McDonough’s skin during a previous encounter and he was looking for his opportunity to “even things up”. A flying kick to the chest did the job, but as he trudged off the pitch, McDonough felt “gutted” he had let Moore down.

Dave Webb replaced Moore in the hot seat, but for Roy it was more of the same. During a pre-season friendly, he offered to help Southend’s “top boys” when a scuffle broke out with Crystal Palace fans. He then tried to reposition Shane Westley’s dislocated knuckles after Palace’s Ian Wright trod on his team-mate’s hand, succeeding only in rupturing the tendons, leaving “soft c**t” Westley requiring five hours of surgery.

Despite another relegation, McDonough’s penultimate season with Southend finished with a bang. On the final day of the campaign, some on-pitch verbals with Bristol Rovers’ Ian Holloway spilled over, sparking a 16-man brawl in the players’ lounge after the game. Reduced to the role of bit-part player in his final season, McDonough still managed to get sent off in a League Cup tie against Spurs, and again the one time in his career he was made captain – the latter for an alleged stamp on Burnley’s Roger Eli. “Most of my red cards were fair enough,” he says. “But that one was a f**king howler. I never touched him.”

In September 1990, he returned for a second spell at Colchester, and was sent off on his first start – but after that, not again for a relatively impressive two years. McDonough wasn’t a changed man exactly, but he was a married one – since June 1988, in a strange twist after his womanising had continued unabated to that point – and at 32, playing in the Conference, he knew this was probably his final shot at a return to the Football League. What nobody could have predicted, though, was the manner in which he did it.

Manager Ian Atkins left after just one season to become coach of Birmingham, and if it was a surprise that McDonough succeeded him, it was also proof that his outward persona didn’t tell the whole story.

“Roy was still a player, first and foremost, and still at the front when it came to the boozing and banter,” recalls Mark Kinsella, the future Republic of Ireland midfielder who was a young pro at Colchester. “But he also took young players under his wing, gave them the lessons of life and football, and demanded 100 per cent in training as well as matches. And in a league where there was a lot of kick and rush, he wanted to play football.” Indeed, the U’s won the Conference and FA Trophy double in record-breaking style, McDonough banging in 29 goals. Sure, his management style was unconventional – he once cancelled training to play indoor cricket, and occasionally played porn videos on the team coach – but it worked.

Roy was still a player, first and foremost, at the front when it came to the boozing and banter. But he also took young players under his wing

Most amusing, though, were his run-ins with Martin O’Neill, then manager of Colchester’s Conference rivals Wycombe Wanderers. McDonough took every opportunity to wind up his more serious, studious counterpart. He once instructed his team to play ‘olé football’ when 3-0 up against the Chairboys, keeping the ball to leave Layer Road in raptures. Another time, having been warned he would be fined if he fielded a weakened line-up for a “meaningless” Bob Lord Trophy match, McDonough named a full-strength team, with every player out of position and ordered not to make a single tackle. Colchester lost 6-2.

The rivalry continued when Wycombe were promoted to the Football League the season after Colchester. McDonough goaded the Adams Park fans following his side’s 5-2 victory, prompting an attempt by Wycombe director and TV commentator Alan Parry to have him arrested for inciting a riot.

By then, though, McDonough was losing favour with the board, despite keeping the club in the fourth tier on a tiny budget. His inability to practise what he preached was wearing thin. Kinsella explains: “Before one game, he said, ‘This lot are going to try to get under our skin. Don’t retaliate. Bite the bullet, play your game and let’s get out of here with three points’. Within 10 minutes he’d been sent off!”

“I never set out to hurt anybody”

While McDonough doesn’t regret the red cards, and is philosophical about the boozing and womanising, he knows his was ultimately a career of ‘what if’s

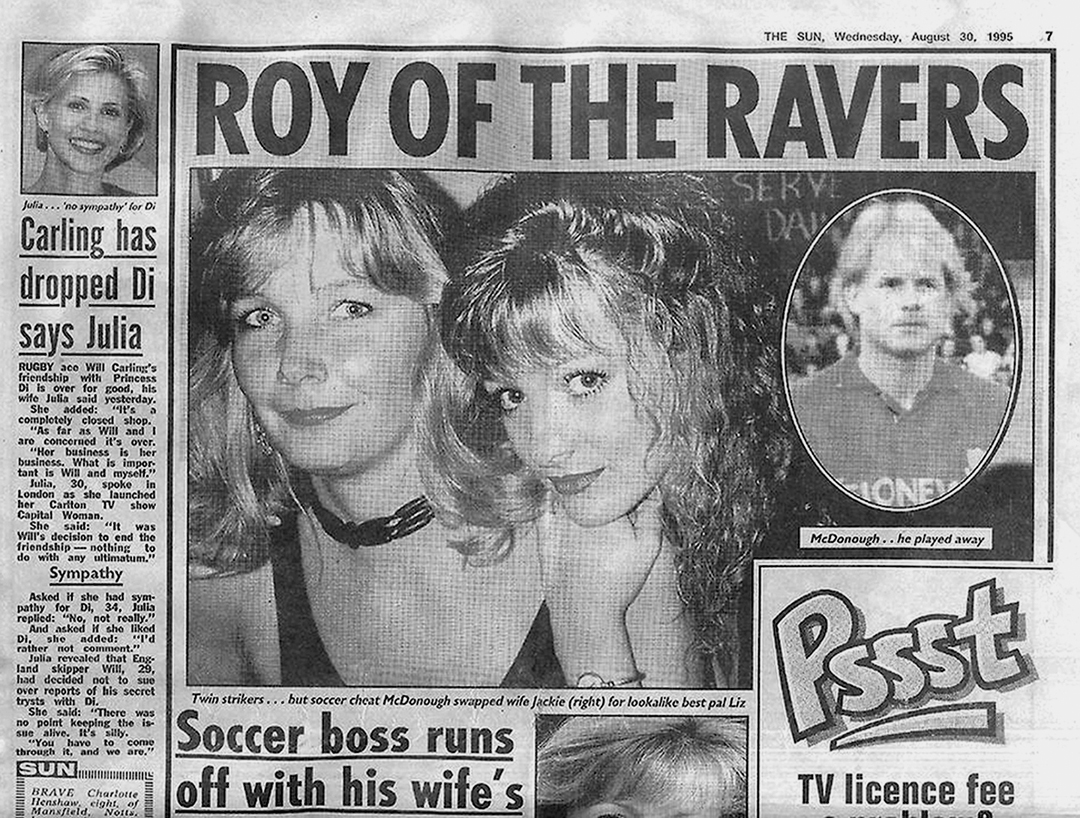

‘ROY OF THE RAVERS’ screamed the headline on p7 of The Sun. ‘Soccer boss runs off with his wife’s lookalike best pal’. Throw in that his wife was the Colchester chairman’s daughter and her ‘best pal’ was the groundsman’s wife and it looked like just the latest chapter in a career of controversy and calamity.

The truth was, McDonough hadn’t been a ‘soccer boss’ for more than a year, and the ‘best pal’ in question is now his wife of 16 years, who, he says, saved his life.

After getting sacked by Colchester in the summer of 1994, McDonough gradually wound down his career in non-league. The red cards kept coming with startling regularity, but the jobs in management did not.

“I still wanted to play, but I was unemployable because after a few bad results the fans would be calling for the club to ‘give the big fella the job’ after I’d made the step up at Colchester,” he explains. “If I’d packed in playing, it would have been much easier for me to get back into management.”

After a successful stint as a car salesman, McDonough moved to Spain, where – after a three-year spell running a Charlton Athletic soccer school – he now flogs property around the swanky La Manga resort.

And while he doesn’t regret the red cards (“I was wholehearted but I never set out to intentionally hurt anybody”), and is philosophical about the boozing and womanising (“it ain’t big and it ain’t clever, but it got me attention”) he knows his was ultimately a career of ‘what if’s.

“On a Saturday night, I watch X Factor and the contestants get kicked out, and a little tear’s running down my cheek – and I know why,” he says. “These people are living their dream, just like I did – then the game kicked me in the nuts.” You could say he kicked it right back.

Red Card Roy, published by Vision Sports, is available to buy online now.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2015 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

RECOMMENDED Revealed! YOUR club's Cult Hero – as voted for by the fans