Mickey, Ricky, Ronnie, Harry and Billy the horse: the FA Cup's 90 minute heroes

From Ryan Giggs to Morton Peto Betts: presenting the men and women (and horse) who have made the FA Cup the world’s most thrilling knockout competition...

Alec Stock

Yeovil 2-1 Sunderland

Fourth Round, 1949

In football seismology, this shock still resonates after almost 60 years – it was voted the FA Cup’s greatest giant-killing in a 2005 poll. In March 1949, star-studded six-times league champions Sunderland, Len Shackleton and all, were dumped out of the FA Cup by a non-league outfit. Not a crack non-league opposition, mind: Yeovil were sixth from bottom of the Southern League. However, the magic of the Cup had clearly stirred the loins of the Glovers’ young player-manager Alec Stock. Still only 29, Stock’s own professional career as an inside-forward with QPR had been banjaxed by injury in the Second World War – in which he worked his way up the Royal Armoured Corps ranks to become a Major. Stock scored the opener and masterminded a 2-1 victory at Huish Park in front of a press scrum so large that desks had to be borrowed from a local school and placed along the touchline. And how Stock loved playing to the gallery. Mindful of the advantage served by Yeovil’s eight-foot slope of a pitch – the grass on which, urban myth suggests, he cut himself – Stock talked it up. He was also an early adopter of nutritional techniques, insisting on a diet of glucose, sherry and eggs for his team.

Out-thought and out-fought, Sunderland somehow forced the tie into extra-time – played due to post-war energy restrictions which banned replays – but Eric Bryant nudged Yeovil ahead again after a mistake by Shackleton. A place in FA Cup legend as giant-killers extraordinaire was cemented: a role Yeovil – Subbuteo’s first non-league team – continued to fill with aplomb, scalping 20 league sides before finally joining the ranks of the 92 clubs themselves in 2003. The 1949 fairytale ended with an 8-0 hiding at Manchester United in front of 81,565 – the largest FA Cup crowd outside of a final.

Alan Sunderland

Arsenal 3-2 Man United

Final, 1979

In the late ’70s, Alan Sunderland was Arsenal’s ultimate ‘big game player’, in an era when the phrase hadn’t even been coined. Put ‘Sundy’ up against a leaky Birmingham defence on a cold afternoon and he’d shrug sulkily and feign disinterest. Place him in life-threatening, backs-to-the-wall situations and he’d miraculously spring into action. Sunderland’s penchant for the big occasion was perfectly illustrated in the ‘five-minute final’ of 1979. Actually, it was his and Brian Talbot’s goal which put Arsenal ahead in the match (both have since claimed they struck the ball simultaneously – although Talbot is officially credited with the strike), before Frank Stapleton added a second shortly before half-time.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

With just three minutes left, Gordon McQueen and Sammy McIlroy pulled United level, the latter claiming: “When I looked around, the Arsenal players were on their knees. They were totally gone.” Sunderland reckons McIlroy misjudged Arsenal’s mood: “We were furious we’d let things slip like that, and we knew we had one last chance to make amends.” With 89 minutes on the clock and the game heading for extra-time, Liam Brady tore forward, laying off the ball for Graham Rix, who crossed hopefully into the United box.

“I don’t actually think anyone was watching the game at that point, except for me,” laughed Sunderland, who slid the ball into the net to make it 3-2 to Arsenal before wheeling away in celebration, mouthing curses (“I still have no idea what I was saying – I lost the plot”), as his blue butterfly collar flapped around in the breeze. “It was a mind-blowingly intense feeling,” he concludes.

Harry Thickett

Sheffield United 4-1 Derby

Final, 1899

Long before Bert Trautmann, the physical courage to play on through pain was a feature of Cup finals. Harry Thickett, though, was the first to begin the match with a serious injury. A United stalwart since 1890, he wasn’t going to allow the small matter of two cracked ribs to stop him turning out. Swaddling himself in 50 yards of bandages so that, as a newspaper report had it, “he resembled a portly mummy”, his bravery was vindicated as he got the better of prolific Derby inside-forward Steve Bloomer. United were a goal down at half-time, but a record 74,000 saw them score four without reply in the second half.

Tim Buzaglo

West Brom 2-4 Woking

Third Round, 1991

No other moment in my life has matched that in terms of pure exhilaration

Not many players can claim to have been carried from the pitch on the opposition fans’ shoulders, but that’s exactly what happened to Woking striker Tim Buzaglo after scoring a hat-trick at The Hawthorns. “No other moment in my life has matched that for pure exhilaration. I can’t describe the feeling,” says the 45-year-old school caretaker, who also played international cricket for Gibraltar. The Isthmian League outfit were four divisions and 120 places below the Baggies when they beat them 4-2.

Nobody believed they had a chance, especially after Albion went one-up. But on the hour, Buzaglo’s incredible adventure began. Team-mate Derek Brown put him through to score an equaliser from outside the box and then, seven minutes later, he notched another with his head.

The hat-trick and the game were finally wrapped up when Buzaglo blasted a left-footed shot into the bottom corner. But it was the Fourth Round match against top-flight Everton at Goodison Park that stands out in his mind, even though Woking lost 1-0. “There were 55,000 there and the playing surface was like a snooker table,” he says. “They treated us like professionals.”

Paul Allen

West Ham 1-0 Arsenal

Final, 1980

“Because I was so young and inexperienced, I played with no nerves at all,” recalls Paul Allen. The Essex-born midfielder, at 17 years and 256 days, became the youngest ever Wembley FA Cup finalist, beating previous record holder Howard Kendall. Allen, who’d started the season in the youth team, bossed the Second Division Hammers’ midfield, and overshadowed match-winner Trevor Brooking in the process.

Allen’s phenomenally hairy team-mates nicknamed him ‘Babyface’; his youthful exuberance and hard running wore down the Arsenal rearguard, which played an incredible 70 matches that season. With just five minutes remaining, the scampering Allen had a chance to add to Brooking’s headed goal, as he bore down on Gunners keeper Pat Jennings. Just as Allen was about to pull the trigger, Arsenal’s lumbering Scottish centre-back Willie Young chopped him at the ankles. Despite the crescendo of boos which rang out from the terraces, Allen remained remarkably diplomatic about the incident.

“I told Big Willie not to worry about it. I’d have done exactly the same in his position. He was a defender and he defended. I rarely look back and think that I could have been the youngest scorer in a Cup Final.” Allen’s stoicism is understandable given that the Hammers held on to their narrow lead.

Despite having the last laugh, the youngster burst into tears at the final whistle. “The heat, the fact that we’d won, and the sheer enormity of the occasion just got to me. It was an unforgettable day,” he said.

Not bad for a player who, in skipper Billy Bonds’ words, was “barely out of short pants, and whose voice hasn’t even bloody broken.”

Roy Essandoh

Leicester 1-2 Wycombe

Quarter-Final, 2001

Second Division Wycombe had performed a minor miracle in reaching the quarter-final stage of the 2001 competition, but an injury crisis was seriously damaging their already slim chances of making it past Premiership Leicester City. Manager Lawrie Sanchez was so short of strikers (Ian Wright and Gianluca Vialli had turned down his ambitious overtures) that he posted a plea on the club website, which was picked up and run as a news item on Teletext. It was spotted by the agent of Roy Essandoh – a Belfast-born Ghanaian who had made fleeting appearances for Motherwell, East Fife and Rushden & Diamonds – and a two-week contract was quickly signed after a brief trial. “I was at a loose end after leaving VPS Vaasa in Finland,” Essandoh recalls.

“I saw Wycombe as an opportunity to make something more permanent in England, but never in my wildest dreams did I expect to make such an impact.” Coming off the bench with 17 minutes remaining, the score at 1-1 and Sanchez sent off for berating the officials, Essandoh headed home the winner two minutes into stoppage-time. It was his first goal in British football. “I didn’t even know some of the players, and the TV commentator had to ask me how to pronounce my name, but then all of a sudden I score this goal and everything goes crazy,” he smiles.

“When the ball came to me I just wanted to make their goalkeeper work, but it was fantastic to see it go in. You know it was something special when people still want to talk about it to this day.” Essandoh also came on as a sub in the Semi-Final defeat against Liverpool, before being released at the end of the season. He went on to play for Barnet, Grays Athletic and Bishop’s Stortford.

Frank Swift

Man City 2-1 Portsmouth

Final, 1934

At half-time, Frank Swift was all but inconsolable. The 19-year-old goalkeeper had enjoyed a good first season in City’s first team, and had become noted for his height and huge hands, but he blamed himself for allowing Septimus Rutherford’s 27th-minute cross-shot to slip through his grasp, giving Portsmouth the lead.

“Never worry,” said City’s centre-forward Freddy Tilson. “I’ll plonk in two second-half.” He took his time, but, after Swift had made a series of fine saves and Pompey defender Jimmy Allen had been forced off through injury, Tilson proved as good as his word. He equalised after 74 minutes before getting the winner with two minutes remaining, converting Alec Herd’s cross. In the City goal, Swift was beside himself, his nerves only increased by the photographers behind his net counting down the seconds.

When the whistle finally went, he collapsed with relief, and had to be half-carried to collect his medal. By then, his error had been forgotten. Swift went on to captain England and became a reporter for the News of the World, who he was working for when he was killed, aged 44, in the Munich air crash.

Stan Mortensen

Blackpool 4-3 Bolton

Final, 1953

I did feel sorry for Morty: he scored a hat-trick and nobody said anything

What does a player have to do to have an FA Cup Final named after him? You’d think scoring the only ever hat-trick in a Wembley final might seal the deal, but not if you have the misfortune to do it when a much-loved legend wins the Cup for the first time, at the age of 38, having turned in an exceptional performance. So what might have been the Mortensen Final became the Matthews Final, and Stan Mortensen was reduced to the curious status of heroic footnote.

Both Mortensen and Stanley Matthews had lost in finals in 1948 and 1951, and with Bolton 3-1 up midway through the second half, it seemed they would miss out again. But then Matthews crossed, goalkeeper Stan Hanson fumbled, and Mortensen poked his second goal of the game over the line.

Bolton held on, and it was only in the final minute that the equaliser arrived, Mortensen crashing in a free-kick after Jackie Mudie had been felled. Wembley prepared for extra-time, but Matthews jinked past the defence once again, and pulled back a cross for Bill Perry to sweep home the winner.

“It doesn’t bother me that my goal has been largely forgotten,” said Perry. “But I did feel sorry for Morty that day because he scored a hat-trick and nobody said anything about it.” Blackpool fans paid a belated tribute to a forward who once scored in 12 successive FA Cup ties by erecting a life-sized statue of him outside the North Stand at Bloomfield Road.

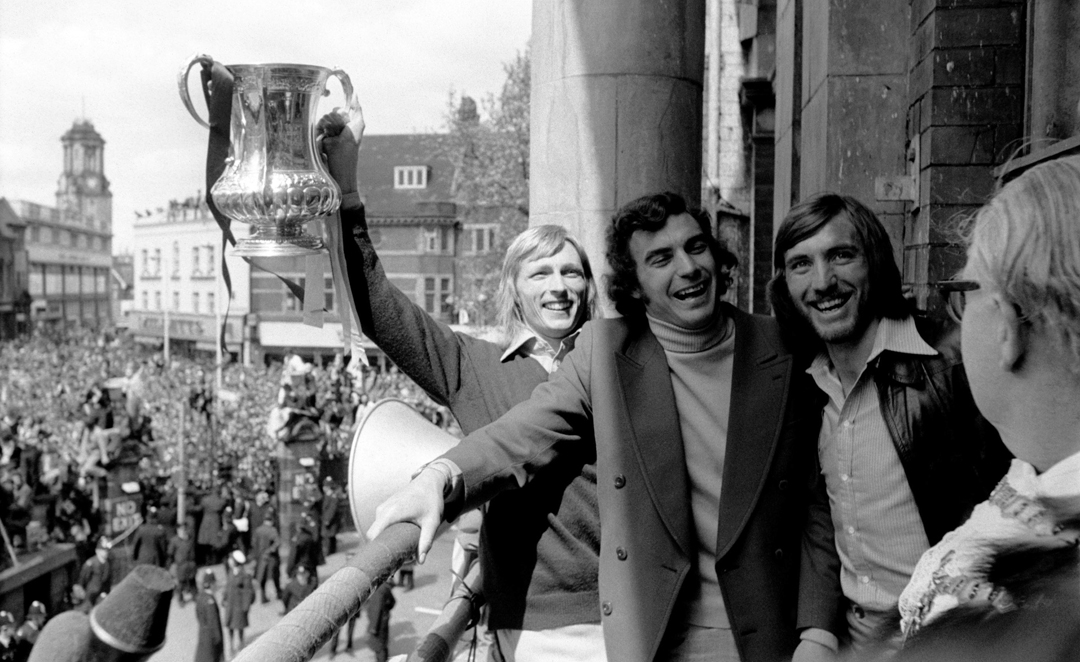

Jim Montgomery

Sunderland 1-0 Leeds

Final, 1973

Trevor Cherry, advancing into the left side of the box, met Paul Reaney’s deep cross with a firm diving header. Goalkeeper Jim Montgomery, having tracked the cross, was forced to change direction, and, plunging to his left, pushed it away. A fine save, but the ball fell for Peter Lorimer, seven yards out with an empty net at his mercy. Instinctively, he side-footed the ball, and so certain was the goal that on ITV Jimmy Hill announced the equaliser. Leeds were level and their FA Cup dream was back on.

Hill had reckoned, though, without Montgomery, and the heroics that had inspired Second Division Sunderland during the greatest, least plausible FA Cup run of them all. The keeper, pivoting up from his left elbow, sprang along the goal-line, got fists to Lorimer’s shot, and pushed it up onto the crossbar.

As it span away, Cherry, still prone, wagged a disconsolate heel, but the ball was gone, and with it Leeds’ belief. Even after a replay, Hill could not believe what he had seen, suggesting first that the ball had hit the stanchion holding up the netting, and then that Lorimer had missed the target. Only on a third viewing did he finally accept that it was “an incredible save”.

Little wonder that when manager Bob Stokoe – clad in trilby, mac and red tracksuit bottoms – made his dash onto the pitch at the final whistle, he headed towards his goalkeeper. “I knew the Cup was ours when I saved that one from Lorimer,” Montgomery said. “It’s all a bit hazy and I’ve no idea what Bob said to me at the end. When he hugged me, I don’t think it was just for those saves in the second half. It was also for some important saves I’d made in earlier rounds – against Manchester City and Arsenal in particular.”

Karen Walker

Doncaster 4-0 Red Star

Women’s Final, 1992

Britain’s most celebrated female footballer racked up a record 12 FA Cup final appearances, lifting the trophy seven times. Yet it was her appearance in the 1992 Final at Tranmere Rovers’ Prenton Park which really set her apart. Having scored a hat-trick in every round, the pressure was on for Walker to repeat the feat in the Final against Red Star Southampton. She duly obliged, walking off with the match ball in a 4-0 rout.

“It wasn’t until I got to the Semi-Final that I realised I’d achieved such a feat,” she recalls. “Then the media jumped on it, but I was confident that I could do it. “Without taking anything away from Southampton, they were a mid-table side and we were red-hot favourites, but it was a wonderful feeling to finally grab the hat-trick. What made it even more special was that the win also secured the Double.”

The hat-trick-clinching goal, especially, remains a vivid memory “simply because of the relief I felt at the time,” she adds. “Joanne Broadhurst put in a great cross and I headed home from the penalty spot. It was one of the proudest moments of my career.” Walker brought down the curtain on her playing days, “but I still play football with the lads at work.”

Billy

Bolton 2-0 West Ham

Final, 1923

“Just ordinary, lass, just ordinary.” For understatements of the 20th century, the words of PC George Scorey to his fiancée when asked about his day at work are up there with the greats. For it was mounted policeman Scorey and his white horse, 13-year-old Billy, who brought order from chaos in the first Wembley final, between Bolton and West Ham. Faced with an official crowd of 123,000 desperate to see the long-awaited new stadium – and many more who had got in by various unofficial means, swelling the attendance to as much as 200,000 – Scorey helped restore order, gradually clearing the pitch.

Miraculously, there were no serious casualties and the kick-off was delayed by just 45 minutes. But with thousands standing on the touchline, ball and players regularly disappeared and the game was little more than a farce. Bolton – forced to walk the last mile to the ground, such was the crush – took the lead through David Jack’s third-minute opener, while West Ham right-half Jack Tresarden was trapped in the crowd after leaving the pitch. And they doubled their advantage in controversial circumstances, as John Smith crashed home after a fan kicked the ball back into play.

The Hammers’ pleas for the game to be abandoned fell on deaf ears. Scorey, who had no interest in football, was full of praise for his trusty steed. “He dominated the crowd by the sheer force of his personality,” he recalled. “Perhaps because he was white he commanded more attention. We were given orders to clear the pitch. Clear the pitch, indeed! You couldn’t see it. I felt like giving it up as hopeless. Anyway, Billy knew what to do. He pushed forward quietly but firmly and the crowd made way for him. They seemed to respect him.”

Ray Crawford

Colchester 3-2 Leeds

Fifth Round, 1971

If their players went to the toilet I wanted two men there as well

“No nerves, no tension, just relax. And you know what, I think we can win.” The bold pep-talk of Colchester boss Dick Graham wasn’t lost on veteran striker Ray Crawford and his team-mates as they ripped into Leeds with the air of a starving man given first go at the buffet.

Leeds, title winners two years previously, found themselves 3-0 down against their Fourth Division hosts within an hour.

The 34-year-old Crawford, rescued from the dole just months earlier, had been a championship winner with Ipswich in 1962 – becoming the first player at Portman Road to win an England cap. With five other U’s players the wrong side of 30, Don Revie’s side, renowned for their guts and ability to ‘win ugly’, came up against a spirit and experience that just would not be cowed.

Crawford had earned the nickname ‘Jungle Boy’ on national service in Malaysia, and certainly proved the king of the Layer Road swingers that day. Still blessed with the physical presence to match anything Norman Hunter and Jack Charlton could throw at him (and sideburns to die for) he took advantage of keeper Gary Sprake’s flap at a cross to open the scoring on 18 minutes.

He was celebrating again six minutes later, hooking home after a collision with Sprake, before Dave Simmons added a third. With Colchester’s two Johns, Kurila and Gilchrist, detailed to shadow Allan Clarke and Johnny Giles wherever they went – “if they went to the toilet I wanted my two men there as well,” said Graham – Colchester were worthy victors, despite a late scare as Hunter and Giles clawed back the deficit to 3-2.

True to his promise in the pre-match build-up, Graham scaled the walls of Colchester Castle, and paid for a fortnight’s holiday for his team and their wives.

Ricky Villa

Tottenham 3-2 Man City

Final, 1981

It's the goal I tried to score all my life and I never managed to do it before or again

Ricky Villa’s solo strike for Spurs in the 1981 Cup Final replay against Manchester City at Wembley lives long in the memory.

A slalom run past three helpless defenders in the penalty area before the ball was fired past Joe Corrigan, it was the goal that so nearly didn’t happen.

Villa had been substituted in the first game (a 1-1 draw) and the press expected him to be relegated to the bench for the return.

But going against popular opinion, manager Keith Burkinshaw kept faith with his Argentinian midfielder and was rewarded with two goals – the first a tap-in, the second a flash of individual brilliance that earned Tottenham a thrilling 3-2 win and was voted Wembley’s Goal of the Century.

How did it feel when you were substituted in the first Cup Final?

Well, I had to accept the decision, despite the fact that it was an FA Cup Final. But as I walked off the pitch, I felt very sad. I thought that it was the end of the Cup Final for me – I didn’t think I’d get on the Wembley pitch again because we were losing 1-0 at the time and I thought we’d lost our chance. But we got an equaliser and so I was very pleased to get the chance to play in the second game. Some of the papers were saying that maybe Ricky Villa won’t be playing in the replay, or that somebody else should be playing. But luckily I was picked.

How did you feel before the game?

I really wanted to prove myself in that game. I said: “Give me the ball and I will do it for you.” I really believed in that. I was always confident before playing football games. I was in good condition, I was fit, I was clever, I was skilful... come on, I can do it!

Your second goal was pure fantasy. What on earth was going through your mind?

It’s funny, because when you’re running at players like that, you’re not thinking about how to finish. You’re thinking about going past people. I remember starting my run and going past one player, past two players, past three players and then suddenly the goal was very close and I put the ball in the back of the net. I say, “Easy!”

That sounds a bit like Pele in Escape To Victory: “I do this and this and this and score...”

Well, it was something I did in training quite a lot, but to do it in a cup final was very special. At that time, I really played Ricky Villa football – I like to play individual football, I like to try to break down defenders with my dribbling. I know the English way is to get the ball down the wings and put crosses in, but dribbling is an important part of the game. If you cross the ball, there can be too many people in the box. In one moment I beat some players and took them out of the game and scored a goal.

Looking back on it, how do you feel about that goal now?

It was the most wonderful goal of my life. I guess it’s the sort of goal you dream about scoring: the FA Cup Final winner, especially when it’s an individual goal where you dribble around a few defenders and tuck it past the keeper. Even now, I look back and feel lucky to have scored such a great goal, because it’s the goal I tried to score all my life and I never managed to do it before or again. Today, it’s one of the moments in FA Cup history that people always talk about. I can’t believe that 25 years on from that goal, people – some of them Spurs fans, some of them fans of other clubs – still want to talk to me about it. I’m so proud to be part of English football history.

Read Ricky Villa’s full account of the 1981 FA Cup Final in Match of My Life: Spurs.

Mike Trebilcock

Everton 3-2 Sheffield Wednesday

Final, 1966

The manager told me I was playing instead of Fred. I could have fallen off my stool

Mike Trebilcock (pronounced Tre-Bilko) was a Cornishman of West Indian descent, quite an exotic character for the English football scene of the 1960s. His consistent goalscoring record at Plymouth brought him to the attention of Everton, who signed him on New Year’s Eve 1965 for £23,000. Trebilcock was soon injured and spent most of his first season at Goodison Park on the sidelines. But then a shock decision by Toffees boss Harry Catterick saw him called up for the FA Cup Final against Sheffield Wednesday ahead of England international and fans’ favourite Fred Pickering.

Trebilcock recalled the moment he found out: “Fred was in there and the manager said ‘At times like this, decisions have to be made and I have to make them’, and he said I was playing instead of Fred. I could have fallen off my stool.” Things weren’t going well for Everton in the Final. Goals from Jim McCalliog and David Ford had put Wednesday 2-0 up, before a Trebilcock-inspired comeback that repaid his manager’s faith with interest. Two impressive strikes from him in quick succession squared the game and minutes later, Derek Temple scored the winner – and things started to get strange...

Eddie Cavanagh

Everton 3-2 Sheff Wed

Final, 1966

Overcome with emotion at the Toffees’ comeback, a portly, balding figure in a suit came charging across the Wembley turf as the Everton team celebrated their equaliser, with several policemen in hot pursuit.

Kenneth Wolstenholme dutifully provided the commentary for the folks at home as the pitch invader was finally grabbed by the jacket – only to slip it off and continue legging it, leaving his pursuers on the floor clutching an empty coat. He was eventually felled by a textbook rugby tackle and hauled away by half-a-dozen huffing and puffing rozzers. Several Everton players closed in to remonstrate, but they weren’t attempting to chastise the intruder, they were telling the police to go easy on him.

Liverpool is a city in size but a village by nature and the players all recognised Eddie Cavanagh from Huyton – an Everton fanatic who had once been on the club’s books. Several of the Everton players had even been in the same team as Cavanagh in the Central League.

During his scuttle across the pitch, Cavanagh somehow had time to congratulate the hero of the hour – “I’d seen Trebilcock and I went for him first. Well, he didn’t know me but I grabbed him, pulled him on the ground” – and pass on some advice to keeper Gordon West: “For God’s sake, don’t let no more in...”

Cavanagh was later dubbed ‘the first hooligan’ for his romp across Wembley, and although his one-man invasion was all about unbridled enthusiasm rather than any malicious intent, a similar action these days would probably earn a life ban from every ground on the planet.

On the day, the police simply threw Cavanagh out of the ground. He vaulted a fence and was back on the terraces in time to see Derek Temple hit Everton’s winner.

Bobby Stokes

Southampton 1-0 Man United

Final, 1976

Tommy Docherty, a manager prone to exaggeration, must have been extremely busy in the days following the 1976 FA Cup Final. On the eve of the game, the Manchester United boss told assorted journalists he’d give his house away, jump into the Thames, eat his hat, and – rather disturbingly – “mud-wrestle my elderly relatives” if Second Division Southampton won the FA Cup. Lawrie McMenemy’s collection of supposed has-beens and journeymen did precisely that, stunning the hot favourites on the drought-parched Wembley turf, courtesy of a late winner from diminutive midfielder Bobby Stokes.

As the press began the countdown to the Final, Stokes was photographed as the archetypal Hampshire yokel: shovelling horse muck at team-mate Mick Channon’s stables, slouched in a wheelbarrow with a piece of straw in his teeth, and quaffing cider in a pub. On the day, he personified Saints’ tigerish spirit, snapping at Lou Macari and Sammy McIlroy’s heels whenever they had the ball.

With Southampton soaking up waves of late United pressure, an inch-perfect Jim McCalliog pass put Stokes through against Alex Stepney, and he slipped it into the far corner of the United net after 83 minutes. United fans claim to this day that Stokes “shinned it in”, and that he was yards offside. Whatever the facts (and camera angles have never proved conclusive), Saints clung on to their lead, and Stokes was elevated to the role of local hero.

Around 250,000 people lined the streets to welcome the team back the day after the Final. Stokes later said: “They came out of hospitals and fire stations, they sat up trees, and made us all feel 20 feet tall. Let’s be honest: we weren’t the best side in the world, but this was our five minutes of fame. I thank the people of Southampton from the bottom of my heart for the best two days of my life.” Having fallen on hard times after his playing career ended, Stokes died of pneumonia in 1995, forever a Saints hero.

Hughie Ferguson

Cardiff 1-0 Arsenal

Final, 1927

Hughie Ferguson found the net at every level of the game. He’d nurtured his skills at the renowned Parkhead Juniors before moving to Motherwell, where he scored an impressive 285 in nine seasons at Fir Park. The powers-that-be north of the border deemed that strike-rate insufficient for the national team.

It was the sort of rejection that would blight Ferguson’s career, and ultimately his life, but he still made the move south to Cardiff in 1925 with a big reputation. Cardiff’s cup run in 1927 saw them defeat Bolton and Aston Villa of the First Division, as well as Chelsea and Reading of Division Two.

Arsenal would meet them at Wembley, and while the Highbury club were not yet the all-conquering force they would become in the 1930s, with Charlie Buchan leading their attack they would start as clear favourites. The Welsh side enjoyed a decent first half, keeping Buchan at bay without creating too much themselves.

It was going to take something ridiculous or sublime to win it, and in the 75th minute the Wembley crowd was treated to the former. Ferguson picked up the ball outside the box and let fly. He didn’t catch it sweetly, though, and the ball seemed to be caught by Arsenal’s keeper Dan Lewis (ironically, a Welsh international).

But with two forwards bearing down on him, Lewis took his eye off the ball, let it squirm under his body and trickle over the line. The FA Cup was leaving England for the first and only time. For Ferguson, things went downhill. He played another season at Cardiff before moving to Dundee, but injury and loss of form saw the forward sink into depression and in 1930, aged just 32, he took his own life.

Harry Redknapp

Bournemouth 2-0 Man United

Third Round, 1984

There’s clearly something about the South Coast air that agrees with Harry Redknapp (OK, keep that theory quiet in Southampton). The Third Round slaying of Ron Atkinson’s boys in January 1984, if not the finest hour-and-a-half of his managerial career, was certainly the pick of his 10 years in charge of the Cherries.

In his first season in the post, with Bournemouth struggling in the lower reaches of the Third Division, Redknapp showed the attitude that has become his stock-in-trade. “There’s a chink in their armour: some of them do not perform when they’re closed down,” he observed of his star-studded opponents.

From the off, Bournemouth’s crunching tackles had the Reds – humbled just a few weeks earlier in the League Cup by Oxford – “visibly frightened”, according to Cherries centre-half Roger Brown. On the hour, they duly cracked. Keeper Gary Bailey failed to gather Chris Sulley’s corner and Milton Graham was on hand to bundle the ball home.

Just two minutes later Bryan Robson, of all people, was dispossessed by Ian Thompson, a £16,000 signing from Salisbury Town, for the second goal. “We don’t get many days like that in Bournemouth,” said a jubilant Redknapp. Atkinson was a little less impressed. “It was a horrible experience,” he said. “We beat Barcelona not long after in the Cup Winners’ Cup and I told Maradona he could think himself lucky he hadn’t been playing Bournemouth.”

Stan Seymour

Newcastle 2-0 Blackpool

Final, 1951

A 5ft 6in left-winger initially rejected as a trialist with the club in 1911 on grounds of his size, Stan Seymour had already won an FA Cup for the Magpies by scoring a rasping drive in the 1924 Final against Aston Villa, Newcastle’s victory in Wembley’s second showpiece ending a dismal sequence of four final defeats in seven years. But Seymour wrote his name large in the competition’s history 27 years later when he became the first man to play for and manage Cup-winning sides.

He steered the Magpies to 1951 Wembley glory with a 2-0 success against Blackpool thanks to a pair of cracking strikes from Jackie Milburn, the second after Ernie Taylor’s cheeky backheel. Seymour served at St James’ Park for more than 50 years all told as manager (twice), director, chairman and vice-president. A man of many talents, he also worked as a sports journalist and outfitter.

Mickey Thomas

Wrexham 2-1 Arsenal

Third Round, 1992

I’ve got so many fantastic memories from my career, but that tops the lot

In the 1979 FA Cup Final, Arsenal had ruined Manchester United star Mickey Thomas’ biggest day by stealing the trophy at the death. The prospect of exacting any revenge with Wrexham – in a clash between the top and bottom teams in the Football League – appeared remote after Alan Smith gave the Gunners the lead shortly before the interval. With eight minutes left, referee Kevin Breen awarded a free kick against David O’Leary outside the box.

Thomas promptly grabbed the ball, spun it around until the valve faced him (the Brazilians claim it gives you more power), stepped back... and the crowd behind the goal prepared to watch it sail high and wide, as his two previous attempts had done.

“I thought I’d smack it as hard as I could and see what happened,” said Thomas. He caught the ball perfectly, it cleared the wall and flew past David Seaman’s despairing dive high into the top corner. The crowd went wild, as did Thomas.

“I ran further in the 10 seconds after I’d scored than I did in the entire second half,” he admitted. With Tony Adams & Co. still protesting long and hard about whether the free-kick should have been awarded in the first place, 20-year-old Steve Watkin hooked in Wrexham’s winner. Pandemonium reigned at the Racehorse Ground.

In the months after the match, Thomas became a minor celebrity after being jailed for producing dud tenners and being stabbed in the backside with a screwdriver after being caught in flagrante with a woman in his car, but his rocket against the Gunners is something else he’ll never be forgotten for.

“I’ve got so many fantastic memories from my career,” he recalls, “but that game easily tops the lot. Arsenal had everything to lose, and they lost it,” adds Thomas, who finally had his revenge.

Tom Woodroofe

Preston 1-0 Huddersfield

Final, 1938

Commentating was still in its infancy, but the art of the gaffe was already well-established. It was only 11 years since the Football League had first permitted games to be broadcast on the radio – when the Radio Times printed a diagram showing the pitch divided into 12 numbered squares to help listeners follow the commentary and visualise the game – but Commander Tom Woodroofe had already gained a reputation.

The 1938 FA Cup Final had been a poor one. After 90 goalless – and largely chanceless – minutes, extra-time, the first ever played in a final, was not a pleasing prospect. As the game entered the 120th minute, fans had already begun to depart and Woodroofe, evidently feeling the tedium, commented caustically: “If there’s a goal scored now, I’ll eat my hat”. At which George Mutch, Preston’s Scottish international inside-right, picked up the ball and set off on a run towards goal.

The England centre-half Alf Young, arguably Man of the Match up to that point, went to close him down, but his tackle was mistimed. Down went Mutch, and, despite doubt as to whether it had been a foul, or even in the area, referee Jimmy Jewell awarded the first penalty kick seen in a Wembley final.

Mutch picked himself up and slammed the ball in off the underside of the bar – the final kick of the match.

That still left Woodroofe’s promise to deal with though, and, beginning a whole chain of public punishments for failed predictions, the BBC ensured he was photographed, napkin tucked into collar, sitting down at a dinner table, knife and fork in hand, set to tuck into his Homberg.

Alan Taylor

West Ham 2-0 Fulham

Final, 1975

Six months earlier, I was playing in front of 1,500 fans at Rochdale

For a rags-to-riches story, you can’t beat the FA Cup Final, and in Alan Taylor the old competition threw up a compelling tale of a player rejected as a kid, working his way up through the non-league game, breaking into the First Division and scoring the goals that won the trophy. Taylor was unknown by his own fans, let alone the opposition – until he scored six goals in three games to take the FA Cup to the East End.

How did you end up at West Ham?

I was released by Preston as a youngster. I had to go down a step and joined Morecambe, did well, and Rochdale came for me. I got 10 goals in five games at the start of the 1974-75 season and signed for West Ham on my 21st birthday. It was daunting, but in John Lyall I had a manager who went out of his way to make sure I settled in.

But you didn’t make much of an impact until the FA Cup quarter-final against Arsenal...

I signed in November, made my first start on Boxing Day, got injured and was out for two months. I returned just in time for the game at Highbury. It would be my first full match and what a match: I scored a goal in each half and we were in the semis! Suddenly the fans were singing my name and I had press following me everywhere.

And so to the Semi-Final and Ipswich Town...

They were building a good young team under Bobby Robson. They were the better side in the first game but couldn’t score against us and we drew 0-0. In the replay I got two goals again and we won 2-1. Six months earlier I was playing in front of 1,500 supporters at Rochdale, now I’m scoring the goals that take West Ham to Wembley.

The hype surrounding the final was that Bobby Moore was playing his old club. Did that take the pressure off you?

That suited John Lyall and me. He preferred it that the press weren't hyping his team, although we were favourites. We did our work and stayed out of the limelight. I think we recorded a bad version of Blowing Bubbles but that was it.

Did Bobby Moore mark you?

Yes. Bobby, bless him, was coming to the end of his career but to be playing at Wembley and being marked by such a legend was incredible. I had to get my head down, get on with my game and try to do what I was there to do. Fulham played well in the first half. We were a very young team: the most senior players were Billy Bonds and Frank Lampard and they weren’t that old. Trevor [Brooking] was the most experienced in terms of playing at Wembley, but in the second half we got going.

Tell us about your first goal.

A strength of my game was reacting in the box and so when Billy Jennings hit a shot which wasn’t held by the Fulham keeper, I was on hand to knock in the rebound. What a moment, all the West Ham fans going mad, and I don’t mind admitting it brought a lump to my throat.

And you didn’t stop there...

Graham Padden hit a volley and once more their keeper couldn’t hold it. Again I put the rebound in the back of the net. The final whistle was something I still think about today.

You now run a newsagent heralded as the tidiest in England. Is it?

I take pride in my shop, yes. My wife and I like to make an impression. It’s much better to have the magazines all in place, the bread lined up, the cans, the sweets, they’re all in order.

As a player you tucked your shirt in, then?

That’s right. How do they run in those baggy shirts today? They drink all the right fluids, eat all the right foods but then have to run with shirts down to their knees.

The armed forces

Sheffield United 3-0 Chelsea

Final, 1915

You have played well with one another... play with one another for England now

When you think of FA Cup Final day, you’ll generally picture blue skies, city streets decked in bunting and coloured balloons and fans trying to out-sing each other until they are hoarse. In 1915, things were different. The skies were grey and damp, the only colour on show was the khaki uniform worn by soldiers enjoying a break from hostilities on the battlefields of mainland Europe, and the only singing was that of rousing armed forces standards.

This was the Khaki Final. Chelsea, in their first final, were playing Sheffield United at Old Trafford in the middle of World War I.

The game itself reflected the nation’s grim predicament – to many fans, the action was dreary and turgid – but they cheerily sang their tunes despite many being wounded from battle. At the end of the match Lord Derby, a special guest at the game, told the players: “You have played well with one another and against one another. Play with one another for England now.” With that, many of the players and supporters made their way from the ground and back into battle in foreign fields.

Steven Gerrard

Liverpool 3-3 West Ham

Final, 2006

Nobody has had an FA Cup final named after them since Stanley Matthews in 1953, but if anybody deserves to, it is Steven Gerrard. The 2006 Final was one of the great clashes, and it was settled by one of the great performances. If it hadn’t been for Istanbul and the comeback against AC Milan in the Champions League final, what happened in Cardiff would have seemed inconceivable; as it was, it was merely remarkable.

An own-goal from Jamie Carragher and a mistake by Jose Reina bundled in by Dean Ashton had given West Ham a 2-0 lead. Even then, Gerrard said later, “inspiring thoughts of Istanbul crept in”. He crossed for Djibril Cisse, who finished superbly.

Nine minutes after half-time, Xabi Alonso lifted a ball into the West Ham box. Peter Crouch won the knockdown. “The set was ideal,” Gerrard says, “and I caught it sweetly. Bang. Back of the net.” Within 11 minutes, though, West Ham were back in the lead, Paul Konchesky’s cross sailing over Reina and into the top corner.

As the clock hit 90, John Arne Riise crossed. Fernando Morientes and Danny Gabbidon jumped for it, and the ball broke loose towards Gerrard, 30 yards from goal. It seemed a long way to shoot from but shoot he did, and it sailed past Shaka Hislop: 3-3.

With the momentum gained, as in Istanbul, Liverpool won the penalty shoot-out. For the second time in a year, they had won a final by scoring three without ever being ahead, and had done so because of their inspirational captain.

Alex ‘Sandy’ Brown

Tottenham 3-1 Sheffield United

Final, 1901

When Tottenham Hotspur reached the FA Cup Final in 1901, they were playing for southern pride. With the rise of professionalism among northern clubs, the Cup hadn't been won by a team south of Birmingham since 1882, but if the Londoners were going to win it, theirs would be a monumental triumph over the odds. Not only did their opponents Sheffield United boast the colossal goalkeeper William Foulke (6ft 4in and 20 stone), they were also one of the best teams in the Football League. Spurs, on the other hand, were playing in the amateur Southern League.

But in Alex ‘Sandy’ Brown they had a forward who couldn’t stop finding the net. Brown hailed from Scotland but had played for Portsmouth before moving to Spurs. Prior to the 1900-01 season he had shown little of the form that would elevate him to become one of the most talked-about centre-forwards in the game, but that year he became the first man to score in every round of the Cup, including all four in a 4-0 win over West Brom in the Semi-Final. A record 110,820 fans (many more climbed the trees outside for a view) crammed themselves into Crystal Palace, but they were silenced early on when United took the lead.

Brown’s equaliser brought the crowd back to life before his brilliant second strike looked to have won the Cup. With north London preparing for the party of its life, United swung in a last-gasp corner that looked to have been dealt with by the Spurs keeper, only for the referee to adjudge that the ball had crossed the line. The replay was in Bolton, this time in front of just 20,000 fans. Once more United took the lead, but once more Spurs bounced back with Brown scoring the third (his 15th of the campaign) in a famous 3-1 victory.

Matt Hanlan

Sutton United 2-1 Coventry

Third Round, 1989

When Matt Hanlan went back to work on Monday, there was no need to ask how his weekend was. Everyone had witnessed the 22-year-old bricklayer’s heroics as his Conference side beat the FA Cup winners of two years before, Coventry City, 2-1 at Gander Green Lane. The non-league side’s manager, an English teacher called Barry Williams, had included in his programme notes the poem If by Rudyard Kipling.

The words proved portentous. On the morning of the match, the team practiced set-plays in a nearby park without any going right, but out on the pitch, three minutes before half-time, all that changed as Tony Rains scored with his head from a corner.

Within minutes of the restart, Coventry equalised through David Phillips, but it was from another Sutton corner 20 minutes from time that the game’s decisive moment came. Played short, it was then clipped into the area, finding Hanlan through a mêlée of players.

“I found myself staring at an open goal with the ball at waist height,” he says. “I remember thinking ‘Don’t miss’, and luckily enough, I didn’t.” The moments that followed the goal are, Hanlan admits, still just a haze.

“I lost it completely for a couple of minutes and then there was the embarrassing celebration – a bit of aMick Channon windmill if I remember rightly."

Mick Jones

Leeds 1-0 Arsenal

Final, 1972

Bought by Don Revie from Sheffield United to “score goals and annoy defenders,” Mick Jones had a fair degree of success in the FA Cup, but as he later admitted “it was a love-hate relationship”. Jones put the Elland Road outfit ahead in the 1970 Final against Chelsea, only to see his team pegged back in injury time. The same was true in the replay, when Peter Osgood and Dave Webb gave Chelsea victory after Jones put Leeds ahead.

In the Centenary Final of 1972, Jones and his team were locked in a tight, nervy game against Cup holders Arsenal, before the Leeds No.9 unpicked the Gunners’ defensive lock. After sprinting down the right, Jones evaded Bob McNab’s desperate lunge, and put a delicious cross onto the head of Alan ‘Sniffer’ Clarke. Cue David Coleman: “ONE-NIL!” As Leeds fans counted down the seconds to the final whistle, and Billy Bremner prepared to lift the trophy which had always eluded the club, bad luck cursed Jones again.

After a seemingly innocuous tangle with McNab in the last minute, he badly dislocated his elbow. Hard man Norman Hunter showed his softer side as he helped Jones, now in a sling and forced to watch on in agony as his side lifted the trophy, up the Wembley steps to collect his medal.

When he reached the bottom again, Jones was placed on a stretcher, waved at jubilant Leeds fans, and was taken away.

Revie labelled Jones “a hero” in the press, but soon regretted the seriousness of the injury; his absence from a league match against Wolves (which Leeds lost) three days later helped cost Leeds the Double.

Charlie George

Arsenal 2-1 Liverpool

Final, 1971

On a swelteringly hot day at Wembley, an exhausted Charlie George, with long hair spilling over his collar, struggled to make an impact. Save for a couple of raking passes, and a 30-yarder that whistled over Ray Clemence’s crossbar, he did precious little. Eddie Kelly and Steve Heighway’s extra-time goals tied the scores at 1-1, but George was told by Arsenal coach Don Howe to “keep out of the way”, such was his minimal impact on proceedings. George, as usual, opted not to listen.

With five minutes of extra-time remaining, he exchanged passes with John Radford and belted a coruscating shot past Clemence to put Arsenal 2-1 up and bring the Double to Highbury. George’s celebration was the most unorthodox ever seen at Wembley. Lying fully outstretched, while remaining poker faced, he waited fully 10 seconds until delighted team-mates picked him up.

The Jesus Christ Superstar pose didn’t go unnoticed, and for years to come opposition fans taunted him about it to the musical's theme tune: “Charlie George, superstar, walks like a woman and he wears a bra”. Over the years, he’s contradicted his own interpretation of the celebration. At the time, he claimed it was “purely spontaneous.”

He added: “If I’d run back to the halfway line and showed no emotion, I’d have cheated the Arsenal fans.” In the years since, he claimed he did it because “I was knackered and wanted to waste time.” He does however, clearly recall bluff Yorkshire team-mate Radford telling him: “Get up, you silly bugger.”

That night, George, his fiancée and the rest of the Arsenal team partied at the Café Royal. Snapped in classic 1970s garb, his kipper tie and butterfly collars earned him the title “London’s best-dressed sportsman”. Jesus Christ indeed.

Gilbert Alsop

Walsall 2-0 Arsenal

Third Round, 1933

As Alsop’s header hit the net, the roar could be heard two miles away

Arsenal were the league leaders; Walsall were struggling in Division Three. It shouldn’t have been a contest, but with the Gunners stricken by a flu bug – then by Walsall’s vigorous approach, and finally by nerves – and the robust Gilbert Alsop having the game of his life, it became the biggest upset the FA Cup had known. Without Eddie Hapgood, Jack Lambert and Bob John through illness, Arsenal wilted in the face of Walsall’s energy.

Their playmaker Alex James was outmuscled, and the inexperienced players Herbert Chapman had brought in to replace his absent stars all had nightmares. Outside-right Billy Warnes couldn’t handle the physicality of the defending, centre-forward Charlie Walsh wasted a hatful of chances and full-back Tommy Black was so flustered that he cynically hacked down Alsop in the box with 25 minutes remaining – something so alien to Arsenal’s ethos that he was promptly transfer-listed.

Bill Sheppard converted from the spot, but that simply confirmed the victory, Alsop having headed home a corner five minutes earlier. It is said that as the ball hit the net, the roar could be heard more than two miles away. Alsop scored 151 goals in 195 appearances in two spells with the Saddlers, and later became groundsman. A stand is named after him at the Bescot Stadium.

Ray Walker

Port Vale 2-1 Spurs

Fourth Round, 1988

On January 30 1988, Tottenham Hotspur were an accident waiting to happen. Meeting Third Division strugglers Port Vale in the FA Cup Fourth Round, Spurs were in the middle of a dreadful run of form, with David Pleat sacked in October, one-time golden boy Ossie Ardiles absent, and a man called Ray Walker about to heap on the embarrassment. Vale’s midfield kingpin, formerly of Aston Villa, put the skids under Terry Venables’ charges with a 25-yard belter and sent them down the windswept hill from Vale Park with little more than a pot of (allegedly) lukewarm tea at half-time to show for their efforts.

On a rutted mudbath of a pitch, Phil Sproson (the nephew of Vale’s record appearance-maker Roy Sproson) doubled the lead before the break. Walker pulled the midfield strings for the 1000-1 outsiders for the trophy, while Chris Waddle & Co, beaten finalists the previous season, were made to look utterly pedestrian.

Vale’s FA Cup glory was to be relived eight years later, going one better by scalping the holders Everton on Valentine’s Day in a Fourth Round replay. The Toffees were seen off by a similar 2-1 scoreline, which also featured a memorable long-range strike from another top-flight cast-off.

Midfielder Ian Bogie, a chubby mate of Gazza’s from his Newcastle days whose late equaliser at Goodison Park had forced the holders back to a heaving Vale Park, showed a glimpse of genius of which his old sparring partner would have been proud. A special mention, too, should go to Vale boss John Rudge, who masterminded both successes.

Bert Trautmann

Man City 3-1 Birmingham

Final, 1956

It was like playing in a thick fog. I only realised I saved five when I saw it on TV

Bert Trautmann – or Bernd, to give him his real name – had been so impressive in 1955-56 that he became the first goalkeeper to be named Footballer of the Year, but it is for an incident in the FA Cup Final, a few days after he received the award, that he will always be remembered. Birmingham were favourites, having scored 18 and conceded just two in reaching the Final, despite not playing a single tie at home, but the recall of Don Revie proved decisive as Man City swept into a 3-1 lead.

Then came Trautmann’s moment, as Peter Murphy chased a through-ball. The German smothered the ball – but clattered his head and shoulder into the forward’s legs. As he got uncertainly to his feet, the crowd broke into a chant of “For he’s a jolly good fellow,” but his unsteadiness on his legs showed serious damage. Nonetheless, reeling around his box, a hand clutched to his neck, Trautmann saw out the rest of the match. It was only later that X-rays showed a broken neck that could have proved fatal, as he explains.

When did you realise how serious the injury was?

At the time I didn’t think about it. In my day, there were no substitutes so I had to carry on. If I’d realised I had a broken neck, I would have left the field. The pain wasn't bad, but it was like playing in a thick fog. I couldn’t recognise anyone. I only realised I saved four or five goals when I saw it on TV afterwards. Anyway, I had to carry on; for me, the FA Cup is bigger than the World Cup.

Did fate bring you to England?

I was a prisoner in Russia in the Second World War, but I escaped after 14 days. Then I spent a year on the Western Front and was caught by the Americans, but I escaped again. The French resistance took me, and I got away. Then I was taken prisoner in 1945 – by the British. I jumped over a hedge straight into a British soldier. The first thing he said was to ask if I wanted a cup of tea. So yes, maybe being captured was fate.

And how did the football start?

In our PoW camp in the north west, a crazy Scottish major said: “Come on, don’t sit around, play football.” We got amateur sides into the camp to play us on a Sunday. Civilians came in to watch us – up to 10,000, because England was pretty dead on a Sunday then. I got hurt and swapped with our keeper while the injury healed – and I never came out of goal. I volunteered to dig out unexploded bombs, then one of the English amateur players said: “Come and play for St Helens Town.” When I joined, they had crowds of 200, but within 18 months they had 6,000. They wanted to have a look at the German.

How did you end up at City?

Frank Swift was retiring so they needed another goalkeeper. I could have gone to Spurs, Arsenal, Liverpool, Manchester United or Burnley, but I chose City.

How did people react to a German so soon after the War?

Up to 40,000 people demonstrated against City signing a German, but a rabbi in Manchester who had fled the Nazis said: “You can’t blame this one German for the war. Let him play.” So I played for City for 15 years. Most people were very kind. When I went back to Bremen in 1949, the people of St Helens gave me a hamper for my family full of food they had saved from their rations. It brought tears to my eyes.

Do you regret staying in England?

I thank the people of England for accepting me. I won the FA Cup, an OBE, and Footballer of the Year. But the most important thing was the way people in Lancashire and England accepted somebody who had been their enemy. My only regret is that I never played for Germany. I’m usually modest, but I believe I could have played for Germany for 10 years.

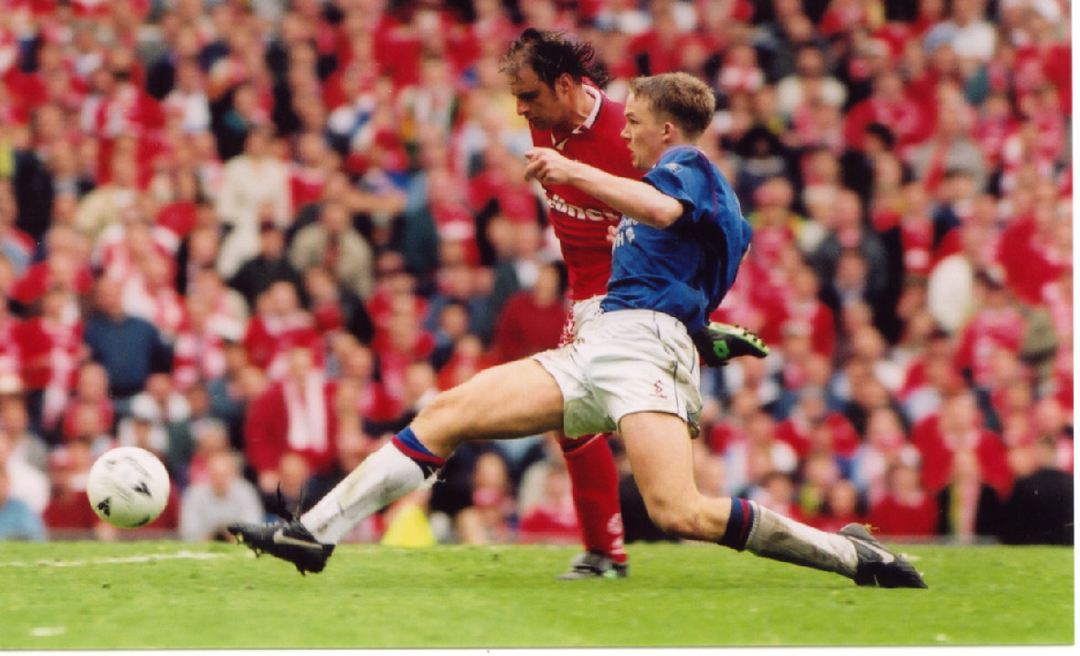

Kevin Davies

Bolton 2-3 Chesterfield

Fourth Round, 1997

Chesterfield may be the fourth oldest club in the country but in 1997 that’s where the third-tier team’s pedigree seemed to end. The Spireites had beaten modest opposition to reach the Fourth Round, but in Kevin Davies they boasted a young centre-forward willing to do to Bolton Wanderers what they had done to so many in recent times. Bolton had been a graveyard club for many big names during the early 1990s, with the likes of Liverpool, Arsenal, Spurs and Chelsea all succumbing to their charms during cup upsets, so the visit of Chesterfield to Burnden Park hardly had tongues wagging.

It would prove to be the last ever cup fixture at the old ground. Davies set about the Bolton back four with gusto from the off, putting Chesterfield ahead after only seven minutes. The home side equalised shortly after, but in the second half, Davies, a strong combative forward, grabbed two more and despite a late consolation, Bolton were out. This may not have been a case of David slaying Goliath – Bolton were still a few months away from returning to the top flight – but it was helped Chesterfield’s march to the biggest game of their lives, a Semi-Final with Premiership Middlesbrough.

In an incredible tie at Old Trafford, the minnows took a two-goal lead, before finding themselves 3-2 down, only to equalise in the very last minute of extra time. They could, perhaps should, have won the game, scoring a goal that was wrongly adjudged not to have crossed the line, and hitting the bar through Davies. They lost the replay but the Cup run catapulted Davies to Southampton (successfully), Blackburn (disastrously) and Bolton, where he spent a decade tormenting defenders the way he once tormented Wanderers' own.

John MacKenzie

Harlow 1-0 Leicester

Third Round, 1980

When Harlow Town of the Isthmian League followed Second Division Leicester City out of Ted Croker’s velvet bag in 1980, Foxes fans laughed nervously but looked on the bright side. After a near-disaster against non-league Leatherhead five years previously, it seemed inconceivable lightning could strike twice even if Harlow had already disposed of Southend United in a Second Round replay. This optimism seemed well-placed when Martin Henderson put City one-up on the half-hour at Filbert Street – almost certainly the first of many.

But Harlow refused to roll over, and found an equaliser deep in stoppage time. For the replay, a crowd of 9,273 crammed onto the muddy slopes surrounding the Hammarskjold Road Sports Centre pitch on the gloomy night of January 8. The match had all the elements of the classic cup tie: the Harlow free-kick hoofed into the Leicester box; the scuffling game of pinball that ensued, and John Mackenzie claiming legendary status when the ball was eventually adjudged to have crossed the line.

Victory meant Harlow had equalled the ‘nine-round record’ in the FA Cup (equalling the feat of New Brighton in 1956-57 and Blyth Spartans in 1977-78), progressing from the first qualifying round to the fifth round proper – a record which stands to this day.

They weren’t finished, either, only falling away at Watford in a buttock-clenching 4-3 thriller. Meanwhile, Jock Wallace’s young City side, spearheaded by Gary Lineker, went on to win the Second Division championship that year; but Harlow had the last laugh when their most famous old boy, Peter Taylor, enjoyed a disastrous spell in charge of Leicester.

Julie Fleeting

Arsenal 3-0 Charlton

Women's Final, 2004

When she played in the US for San Diego Spirit, the charismatic Julie Fleeting once celebrated scoring a goal by pretending to ‘mark her territory’ on a corner flag. After moving to the Gunners, she soon gained cult hero status. Fleeting’s Arsenal team-mate, England international Faye White, labelled her “a superwoman”.

A PE teacher in Ayrshire by day, Fleeting had captained Scotland against Germany in a vital Euro 2005 qualifier the day before Arsenal took on favourites Charlton in the FA Cup Final at Loftus Road.

Having scored her 88th international goal against the Germans, she boarded the flight to London, had a brief training session prior to the match and promptly scored a hat-trick to secure the trophy for the unfancied Gunners. All this despite a serious leg injury sustained during the Scotland match. At the final whistle, the 24-year-old was hoisted shoulder-high by her team-mates and paraded around the stadium.

Not only did her heroics make her an icon of the women’s game, but her ludicrous schedule sparked fury among journalists. “It’s impossible to conceive that Thierry Henry would ever be asked to undertake such a punishing timetable,” wrote a Times columnist. “If the women’s game in Britain is to gain further recognition and respect,” argued US legend Mia Hamm, “then the likes of Julie Fleeting need to be given the time and space in their preparation to flourish on the pitch.”

Fleeting remained diplomatic about the entire affair, content to bask in the glory of joining the pantheon of Gunners FA Cup-winning legends. “I felt on top of the world that afternoon,” she said.

"And the fact that more than two million watched on television suggests the women’s game is certainly moving in the right direction”.

Morton Peto Betts

Wanderers 1-0 Royal Engineers

Final, 1872

Betts played up front in an attack-minded 1-1-8 formation despite being cup-tied

According to The Field sports paper, the first-ever FA Cup Final, played out between ex-public schoolboys and an army regiment, was quite a spectacle: “the fastest and hardest match that has ever been seen at The Oval,” featuring “some of the best play on their [Wanderers’] part, individually and collectively, that has ever been shown in an Association game.” The final boasted not only the first recorded injury (Lieutenant Cresswell broke his collarbone after 10 minutes, but played on), but also the only Cup final winner to be scored by a ringer.

One-time England goalkeeper Morton Peto Betts usually played as a full-back for Harrow Chequers, but on this occasion he played up front for Wanderers in an attack-minded 1-1-8 formation, appearing cryptically on the team-sheet as ‘AH Chequer’. Even though Harrow had withdrawn from the tournament without playing a game, Betts was still cup-tied under FA rules. A curious oversight, then. But not enough to stop Betts making history with a tap-in following a run by Robert ‘the Prince of Dribblers’ Vidal.

Alan Pardew

Crystal Palace 4-3 Liverpool

Semi-Final, 1990

Making their way to Villa Park on a sunny spring Sunday morning, Crystal Palace fans could be excused for wondering – even worrying – about their club’s fate. Sure, an FA Cup semi-final was a moment to cherish for a side promoted only 11 months earlier, but their opponents, champions-elect Liverpool, had taken them apart in the autumn at Anfield; 9-0 at any level is a hammering, but in the top flight it’s embarrassing.

This was going to be tricky. Alan Pardew was a hard-working midfielder in Steve Coppell’s Palace team, but with Rush, Barnes and Hansen on the pitch his was hardly a name on the neutral’s lips.

The game went to form in the first half, Ian Rush putting the Reds ahead, but Palace came out for the second period like a team who had, quite frankly, had enough. Mark Bright equalised after only 16 seconds and suddenly Liverpool looked rattled. Gary O’Reilly then put the Londoners in front but they were clawed back by a superb Steve McMahon strike before a John Barnes penalty looked to have taken Liverpool to a third successive final.

With two minutes left, however, their shaky back four allowed Andy Gray to head home an equaliser and suddenly it was game on again. Liverpool were an ageing team. They would go on to clinch the title but there was now fallibility in their play, a creakiness Palace were in no mood to ignore.

Four minutes into the second period of extra-time they won a corner, Andy Thorn flicked on and Pardew headed past Bruce Grobbelaar to send the Palace fans bananas. The superstars had been banished and Pardew’s name was sung all the way home.

Jack Tinn

Portsmouth 4-1 Wolves

Final, 1939

Mind games are nothing new. Pompey boss Jack Tinn, sick at losing out in the 1929 and 1934 finals, decided it would be third time lucky. For the Blues’ 1939 FA Cup run he adopted a pair of ‘lucky’ white spats, fitted first left, then right, before each match by his ultra-superstitious winger Freddie Worrall.

Tinn’s masterstroke came in the dressing room before the Final against red-hot Wolves, Cup favourites from the off: on seeing a programme being handed round for the players to sign, he announced that the opposition’s signatures looked “shaky”.

The psychological tricks worked a treat. Wolves, their own pre-match publicity detailing a dreamed-up diet of stamina-enhancing monkey glands, were made monkeys of by unfancied opponents fighting the drop. Bert Barlow, a recent signing from Wolves, opened the scoring, with John Anderson and Cliff Parker (2) getting the others.

The outbreak of the Second World War meant Pompey got to keep the Cup for a record seven years – Tinn spent one night during the Blitz hiding with the trophy in a cupboard under his stairs. Worrall, who played with a rabbit’s foot in his shorts and a sprig of lucky heather, died on Friday 13.

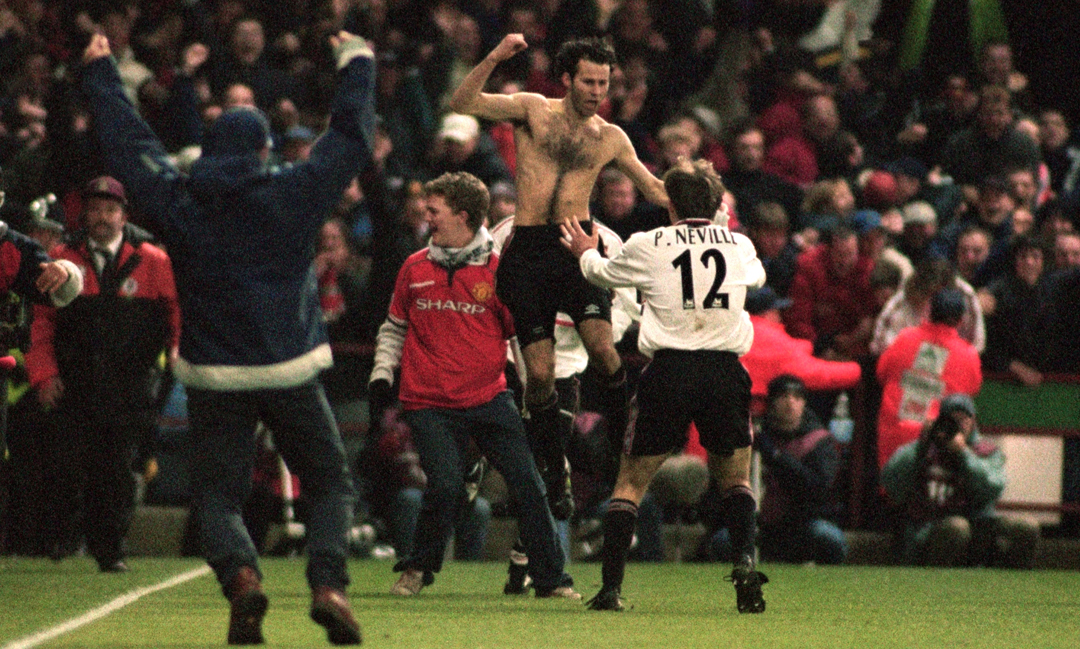

Ryan Giggs

Arsenal 0-1 Man United

Semi-Final, 1999

Did he even have his shirt off? He had such a rug on him you couldn’t tell

“I can’t believe I took my shirt off like that,” says Ryan Giggs. “When I watched it on TV, I was so embarrassed. I had never done that before and I don’t think I’ll ever do it again.” It’s something of a shame for the Old Trafford legend that the greatest goal of Ryan Giggs’ career, and perhaps FA Cup history, is best remembered for that ill-conceived celebration. Having single-handedly tied Arsenal’s ageing famous back five into arthritic knots, the usually reserved Welsh wizard went potty.

Tearing his top off to reveal a Chewbacca-esque physique, Giggs hared down the touchline twirling the shirt over his head, leaving United fans thrilled and amused in equal measure. “Did he even have his shirt off? He had such a rug on him you couldn’t really tell,” says Paul Davies, editor of the Red Devils’ matchday programme, United Review. United fans weren’t complaining, though.

Until that moment, their side had been battling to hold on to the game, not to mention their treble aspirations. With Roy Keane sent off and Peter Schmeichel saving a penalty, Arsenal looked to be closing in on victory.

Then, with just 11 minutes to go, Giggs picked up the ball on the halfway line from a misplaced Vieira pass. “I felt our best chance was to play for penalties,” remembers Davies, “so when I saw him start going, I thought, ‘Go on. Hang on to the ball. Get it away from our goal’.” Giggs, however, had something else in mind.

A master-class in close control left the Gunners’ back-line looking like Keystone Cops before the left-foot Exocet ripped into the roof of the net. “I just remember the release of adrenaline when it went in,” says Davies. “As a United fan, I’ve been chasing that high ever since.”

Roger Osborne

Ipswich 1-0 Arsenal

Final, 1978

Roger Osborne must have been born under an unlucky star. Despite scoring the winning goal in an FA Cup Final, the unfortunate Tractor Boy is now largely remembered for celebrating so exuberantly that he fainted.

Having narrowly missed out on the final three years earlier, Ipswich were determined to get their hands on Big Ears this time around. They arrived at Wembley thanks to a 6-1 thumping of Millwall and were setting about Arsenal with similar intent. Despite their superiority, however, Bobby Robson’s team could not find the net.

“We had four or five chances to score,” remembers Osborne. “Pat Jennings had made some excellent saves, and we’d hit the post twice as well as the bar. It looked like our luck wasn’t in.” Then, in the 77th minute, Ipswich’s Dave Geddis out-sprinted Sammy Nelson and turned in a cross. The ball rebounded off Gunners centre back Willie Young and fell into the path of the onrushing Osborne.

“I had a bit of criticism throughout my career for not using my left foot,” remembers Osborne, “but that was the one occasion I got it right.”

The midfielder began pogoing ecstatically until he was completely mobbed by team-mates. At this point he simply passed out on the pitch. Whether it was from excitement or exhaustion nobody was quite sure, but two minutes later the match-winner was carried off and Robson was forced to replace him. Ipswich held on and won the game 1-0 but even to this day it’s the swoon that’s never forgotten.

Lawrie Sanchez & Dave Beasant

Wimbledon 1-0 Liverpool

Final, 1988

The evening of the Final was one of the most subdued the Crazy Gang ever had

You can always rely on John Motson. In 1988, with Wimbledon players, staff and fans revelling in the sound of the referee’s final whistle, the sheep-skinned one piped up with “the Crazy Gang have beaten the Culture Club”. He was spot-on. As Liverpool stood on the brink of a second double in three years, they came across the one team that cared little for reputations: in fact, Wimbledon thrived on destroying them. And in goalscorer Lawrie Sanchez and penalty-saving goalkeeper Dave Beasant, they had two heroes.

Is it true you were in the pub the night before the match?

Lawrie Sanchez We were all in the hotel restaurant, thinking about the game, and we got a bit edgy and nervous. Alan Cork asked Bobby Gould if we could go to the pub. Amazingly he said yes, so we went down there and had a few pints. Not loads, just a few Guinness. There were a few fans in there, and they couldn’t believe what they were seeing.

What was the dressing-room like before kick-off?

Dave Beasant It was quite calm, but then you hear Abide With Me being played and it hits home. In the tunnel we were very vocal but it wasn’t anything new, we weren’t suddenly trying to upset Liverpool. Vinnie [Jones] and Fash [John Fashanu] had their ‘Yidaho’ cry that they always did. It was an old cowboy shout before going into battle.

What were your tactics?

LS We had Dennis Wise on the right doubling up on John Barnes. Terry Gibson was asked to mark Alan Hansen. That sounds silly, but we felt if you stopped Hansen playing the ball from defence you could upset them.

Tell us about the goal.

LS We felt that, as good as Liverpool were, they could be susceptible to a good set-play. With Wisey taking the free-kicks I was confident. I shouted to Corky to go near-post, and I got in behind him, glanced it in and suddenly Wisey’s locked himself around my body.

What about the penalty?

DB Brian Hill gave the penalty that never was. John Aldridge was brought down by Clive Goodyear, but it was a great tackle. John was embarrassed, I think, but must have been confident because he’d scored so many that season. I’d studied his technique and I knew what I was going to do. I spoke to John Motson before the game. I told him there and then exactly what would happen and there I was, diving to my left.

How was Lady Diana?

DB Vinnie and Fash had bouquets of flowers they were going to give her but they binned them on the way up. She came over to me and said, “You’re a big boy, aren’t you?”

Did the Crazy Gang live up to their name that night?

LS It was one of the most subdued nights out we ever had. We got straight into the champagne but we were so knackered. I left at about 11. I was falling asleep at the table. I went back to the hotel and asked for a newspaper. Which one? Every one!

How much did winning the Cup in 1988 change you all and the club?

LS Sam Hamman summed it up when he said that by winning the FA Cup Wimbledon had lost their virginity. We knew the value of ourselves as players and it was no coincidence that after the final, most of us went on to win caps. What is sad is that while it was the peak of the club’s history, it was also the beginning of the end.

David Seaman

Arsenal 1-0 Sheffield United

Semi-Final, 2003

It is the curse of goalkeepers to be remembered for their mistakes, but when David Seaman’s name is mentioned to anybody who witnessed Arsenal’s Semi-Final victory over Sheffield United at Old Trafford in 2003, the first image that springs to mind will not be the flat-footed flailing against Nayim, or Artim Sakiri, or even Ronaldinho, but his barely believable save to deny Paul Peschisolido.

Robert Page knocked the ball down, Carl Asaba hooked it across goal, and as the substitute won the header six yards out and angled it away from Seaman towards an empty net, it seemed for all the world he would steal an equaliser with just six minutes remaining.

Seaman, though – in his 1,000th appearance in senior football – sprang across goal, leaping backwards and to his right, snapped out an arm, and, as though in a gravity-defying horizontal juggle, flipped the ball not only away from goal, but also away from on-rushing forwards.

“I thought it was in, to be honest,” Seaman said. “I just flung my arm and tried to get something on it.” It would have been a remarkable save in any circumstances, but given that it came from a 39-year-old who was supposedly suffering a hamstring strain it was truly extraordinary, particularly as he had been widely written off – and his England career ended – when he followed the aberration against Brazil in the World Cup by allowing a corner to fly straight in over his head against Macedonia.

With Seaman captain in the absence of the injured Patrick Vieira, Arsenal went on to beat Southampton 1-0 in the Final, so earning him a fourth and last Cup-winners medal, to go with three league titles, the League Cup and the 1994 European Cup Winners’ Cup. Not bad for an old bloke with a pony-tail.

Jimmy Melia

Brighton 2-2 Man United

Final, 1983

Brighton were relegated from the top flight in Jimmy Melia’s first season in charge, but enjoyed the considerable consolation of reaching their first FA Cup Final. The Seagulls were led out at Wembley by a character so unique he even eclipsed fellow Scouser Ron Atkinson, who strode alongside him as Manchester United boss.

The players dubbed Melia ‘Coco the Clown’ for his hairstyle: bald on top, bushy round the sides. Despite his advancing years, he was often spotted out on the Brighton disco scene in his trademark white slip-ons, judging beauty contests and dancing the night away with his young girlfriend.

Brighton managed a 2-2 draw in the “and Smith must score” Final, but were simply blown away by United in the replay, 4-0 being the biggest winning margin in an FA Cup final for 80 years. Melia’s playboy image made him enemies in the boardroom and, as the Seagulls struggled in Division Two, he was sacked by October.

However, no one could force him to go with dignity. The following week, Melia paid his money at the turnstiles and, carried on the shoulders of fans and waving a scarf, led the chanting for the chairman’s head from the terrace.

Lee Martin

Man United 1-0 Crystal Palace

Final, 1990

There were rumours that Alex would go if we didn’t win the match

Lee Martin is assured of a place in FA Cup history for his replay winner against Crystal Palace, but for many Manchester United fans, his solitary strike in 1990 is regarded as the most important goal in the club’s history.

After five years in the managerial hot-seat and without a pot to show for his troubles, boss Alex Ferguson was skating on very thin ice.

Many believe defeat against Palace would have signalled the end of the road, but Martin’s 59th-minute right-foot thunderbolt proved to be the true start to a reign that has since made Fergie the most successful manager in British football history. As United stepped out for the Thursday night replay, following an enthralling 3-3 draw five days earlier, thoughts of championship domination and European Cup success were light years away.

Indeed, for Martin, his hopes and ambitions were far more immediate. “There were rumours that Alex would go if we didn’t win, so in many ways it allowed him to stay on and begin his amazing success, but as a young player, you don’t really take notice of those things. We felt we should have won the first match and because that game was so exciting and open, the replay was never going to hit the same heights. I was just delighted to play my part and score the winner.”

Martin, who went on to play for Bristol Rovers and Huddersfield, missed out on a place in the Cup Winners’ Cup victory against Barcelona the following season, and a title medal two years later. Yet it was the left-back’s drive past the despairing dive of Nigel Martyn which set the tone. “You never know what might have happened had we not won that game,” he muses.

Pat Davies

Southampton 4-1 Stewarton & Thistle

Women’s Final, 1971

Forget Bend It Like Beckham – 45 years ago the women’s game was in the Stone Age, having made little progress since it was banned by the FA in 1921 for being ‘distasteful’. The euphoria of 1966 gave it a kick-start, however, and in 1971 the Crystal Palace Sports Arena hosted the first Women’s FA Cup Final.

The game was set alight by a five-foot-tall 15-year-old called Pat Davies, who bagged a hat-trick to seal a comfortable 4-1 victory. “She was a natural goalscorer,” says team-mate Sue Lopez. “You only had to give her the ball and she was away.” Southampton dominated the cup for the next two decades while Davies went on to represent her country.

Chris Kelly

Leatherhead 2-3 Leicester

Fourth Round, 1975

Having already seen off League opposition in Colchester and Brighton, there was a swagger about Leatherhead in the build-up to the Fourth Round. The Isthmian League side opted to switch their tie against Leicester City from Fetcham Grove to Filbert Street, while striker Chris Kelly – aka ‘The Leatherhead Lip’ – issued Muhammad Ali-style knockout predictions to any tabloid that would listen.

Kelly’s threats, however, were by no means empty. First Division City’s gameplan was in disarray as early as the 12th minute as the Tanners went 1-0 up, McGillicuddy getting to a low cross and heading past Wallington from six yards.

Worse was to come on the half hour when Kelly – inevitably – repeated his scoring feat against Brighton, nodding in a looping header from a free kick. As Leicester’s Alan Birchenall recorded: “Jimmy Bloomfield was so aghast at half-time he didn’t know what to say.”

The moment that changed the game came when Kelly, rounding the keeper for 3-0, had his shot cleared off the line by Steve Earle. Leicester fought their way back into the match with a Jon Sammels header, while Earle proved his attacking worth to equalise and Keith Weller sealed the tie for City.

Even so, Match of the Day was scary viewing for Foxes fans that Saturday night. Leatherhead were back on the giantkilling trail in subsequent seasons, scalping Big Ron’s Cambridge and Paddy Crerand’s Northampton Town. In all, Kelly scored 150 goals in nearly 500 Leatherhead starts.

Keith Houchen

Coventry 3-2 Tottenham

Final, 1987

Policemen were coming in and filling their helmets with champagne