Miners vs silk-wearers: Why Lyon vs Saint-Etienne is more than a game

They used to say Saint-Etienne was a suburb of Lyon, but their team ruled the roost. Then the big-city boys came good... In 2006, FourFourTwo's Matt Spiro investigated the most British derby in France...

The Saint-Etienne fans are presenting a bold front as they hop off their buses and are frogmarched into the Virage Sud of the Stade Gerland by a gaggle of riot police.

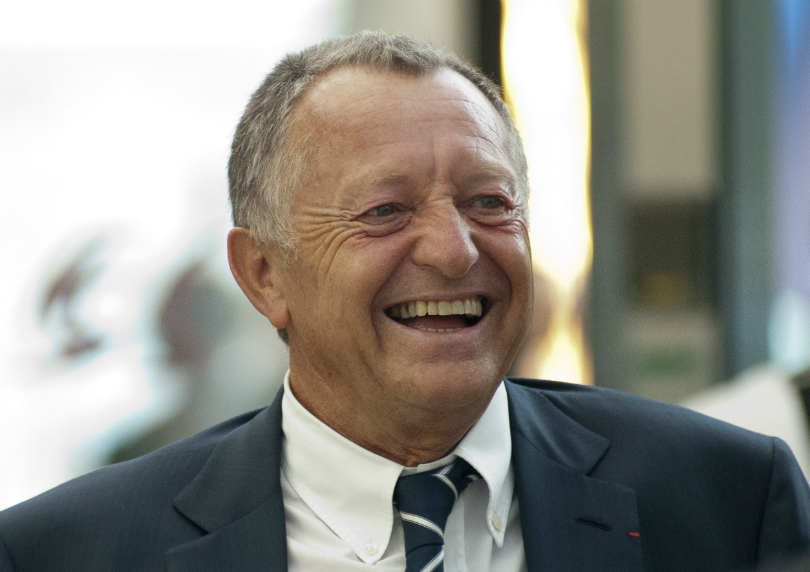

France’s biggest local derby is two hours away and the Stephanois announce their arrival at the home of the newly-crowned champions with a series of hostile anti-Lyon chants. Jean-Michel Aulas, Lyon’s smug president, comes in for the most vehement abuse, closely followed by turncoat goalkeeper Gregory Coupet who made the unforgivable trip of 38 miles from Saint-Etienne to Lyon 10 years ago.

“Bring out Coupet’s missus, bring us the little whore,” goad a posse of green-clad supporters, before chanting their support for Fabien Barthez, Coupet’s World Cup rival. A policeman has to intervene when one supporter wearing an AC Milan shirt with ‘Inzaghi’ on the back breaks menacingly from the pack and starts to taunt passers-by with shouts of “Milano! Milano!”

Yet for all their bravado, the Saint-Etienne boys aren’t a particularly scary sight. They have defiance in their voices but it is with great trepidation that they shuffle into enemy territory on this rainy April evening. It’s going to be a long night and they know it.

Five-star Lyon

Celebrating our fifth title with a firework display in front of the Saint-Etienne fans is a dream come true. Life doesn’t get much sweeter than that

Filippo Inzaghi and AC Milan may have ended Lyon’s Champions League dreams at the quarter-final stage for the third year running, but in France nobody can stop Gerard Houllier’s team. When FourFourTwo visits at the fag-end of another dominant season, they’ve just clinched the title for a record fifth consecutive year – eclipsing Les Verts and Marseille who won four in a row – and tonight represents the first opportunity to celebrate with the fans.

“Celebrating our fifth title with a firework display in front of the Saint-Etienne supporters is a dream come true,” chortles Aulas. “Life doesn’t get much sweeter than that."

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The driving force behind Lyon’s dramatic transformation, Aulas indulges in loose and often pompous talk which has aggravated relations between the clubs considerably in recent times. Indeed it was his careless ‘slip of the tongue’ in 2000 that ultimately led to Les Verts being relegated (more of which later). He remains Saint-Etienne’s enemy No.1.

There was a time, as Aulas no doubt recalls, when Saint-Etienne were the undisputed kings of French football. But le club mythique, as they are still called in the media, have been in disarray for much of the past two decades. This week has been no exception.

Le club mythique, as the media still call Saint-Etienne, have been in disarray for two decades

A calamitous run has seen them plummet from third place in January to the bottom half of the table, prompting coach Elie Baup to offer his resignation. Speculation that goalkeeper Jeremie Janot has also purchased a Milan shirt and is planning to wear it in the derby brings some light relief to their long-suffering supporters.

Lyon’s failure to break through in Europe is all Saint-Etienne have to cling to these days, but luckily for them it is an issue that rankles enormously. “For his own sake Janot had better not come wearing a Milan shirt,” Houllier warns.

Not that the former Liverpool boss has any objection when his own players ask if they can paint their faces and dye their hair for this special occasion. The champions look more like a circus act than a crack football unit when they run out to a heroes’ ovation. Sylvain Wiltord resembles a spaceman with his big, bald head plastered in white paint, Coupet’s flowing red locks are fetching (if a little girly), and the blue-and-red war stripes on Cris’ cheeks make the giant Brazilian more terrifying than ever.

Saint-Etienne clearly struggle to see the funny side as their tough-tackling captain Julien Sable rakes his studs down the back of Juninho Pernambucano’s leg in the first minute. “I hope I didn’t smudge your make-up,” Sable reportedly utters as he helps the Brazilian midfielder to his feet.

But Sable’s crude lunge turns out to be all the resistance the visitors offer. They barely see the ball for the next 89 minutes as Lyon ping it around with style and verve. It finishes 4-0 – Lyon’s biggest derby win since 1962.

“So much for the AC Milan shirt. The only disguise Janot brought with him today was his invisible man outfit,” laughs one local journalist.

As if witnessing Lyon’s demonstration was not painful enough, the away fans are locked in for an hour of celebrations: samba dancing, champagne spraying and a highly impressive firework display are all on the menu. Some try to make a quiet exit but are forced back in by heavy-handed riot police only too happy to let fly with the tear gas.

Spluttering, crying and seething, the Stephanois have plenty of time to reflect as they look down on the joyous scenes. How, they must be wondering, have their bourgeois neighbours, who weren’t even that interested in football 10 years ago, wrested the regional power so dramatically away from their beloved club? And how are they possibly going to get revenge for tonight’s humiliation?

NEXT: "For the first 20 minutes nobody pays attention to the ball, they just fight"

Turning of the tides

As a rule the French don’t go in for derbies. PSG-Marseille is perhaps the nation’s most volatile showdown but the rivalry was created more by the media than by traditional grudges. Local derbies are hard to come by simply because no town has more than one decent club. Northern teams Lille and Lens don’t get on well and Nice-Marseille is described as le derby du sud, but neither musters the same intensity as France’s leading regional tussle.

Lyon versus Saint-Etienne is perhaps the only match in France that resembles a true British derby

“Lyon versus Saint-Etienne is perhaps the only match in France that resembles a true British derby,” says Lyon director of sport Bernard Lacombe. He should know: Lacombe was Lyon’s centre-forward for 10 years before joining the opposition for one ill-fated campaign.

“It’s like Arsenal-Tottenham or Manchester City-Manchester United,” he continues. “Local pride is at stake and people talk about the derby for weeks and weeks. They’re always tasty matches, too. I can recall Sir Alex Ferguson saying that for the first 20 minutes of a United-City game nobody pays attention to the ball, they just fight. It’s the same when Lyon play Saint-Etienne.”

As with any good derby, the rivalry is steeped in history. The traditionally working-class Stephanois have rarely seen eye to eye with their haughty, aristocratic neighbours, and local spats date as far back as the 18th century when the silk-producing Lyonnais would raid neighbouring villages for cheap labour.

Even then the Stephanois displayed a surprising determination to remain independent of Lyon. During the French Revolution they secured the autonomy they had been craving after refusing to support a political uprising in Lyon against the Jacobin Government. Much bloodshed ensued and to punish the Lyonnais further the Rhone-Loire departement was split in two.

Now the capital of its own departement, the Loire, Saint-Etienne expanded rapidly as coalmines and factories sprouted all over. Yet despite the town’s growing industrial importance, Lyon continued to cast a shadow and the underlying fear that Saint-Etienne might one day be classed a suburb of Lyon never disappeared.

Something else was needed, a more public display of strength that would give Saint-Etienne its own identity, recognisable throughout the country. It arrived in the form of an outstanding football team.

First France, then Europe

L’Association Sportive de Saint-Etienne was formed in 1933 and were firmly established by the time Olympique Lyonnais arrived 17 years later. They picked up the first of their 10 league titles in 1957 and then, thanks to the appointment of visionary president Roger Rocher and the fervour of a football-mad public, Les Verts became France’s dominant force, winning four more titles in the 1960s.

Derbies were often one-sided affairs, with Saint-Etienne regarding the biannual thrashings of Lyon as light relief from their pursuit of the Holy Grail: the European Cup.

I don’t want to be mean but I just don’t think Lyon are top-flight material. That was too easy

In 1969, after watching Les Verts come from two down to beat Bayern Munich 3-2 in a gruelling contest, the Lyon players claimed they would “eat them alive” in the derby three days later. Angered by the boast, Saint-Etienne stormed to a 7-1 away win to follow up the 6-0 hammering earlier in the season. “I don’t want to be mean but I just don’t think Lyon are top-flight material,” commented Saint-Etienne’s Yugoslav winger Spasoje Samardzic. “That was too easy.”

The jokes began to flow and while most people in Lyon were too stuck up to worry about a working-class sport like football, the players found it harder to take. France coach Raymond Domenech, the hard man of the Lyon defence for seven years, admits the harrowing defeats left him with an irrational dislike of the colour green.

The colour green gives me acne. One green is OK, but 30,000... that can do real damage

“I like acting because in theatre green is a cursed colour,” Domenech writes in the book Histoires du Derby. “I like Roland-Garros but not Wimbledon. I dream of pitches painted blue and red. At home I paved over my lawn so that I wouldn’t have to look at green when I got up. The colour green gives me acne. One green is OK, but 30,000... that can do real damage.”

President Rocher was particularly adept at getting under the skin of Lyonnais. A provocateur par excellence, Saint-Etienne’s revered president was renowned for his anti-Lyon barbs. “If Saint-Etienne are a locomotive, then Lyon are a freight train,” was one of his favourites. But it was another comment made when Les Verts were at their peak that would truly warm Saint-Etienne hearts.

In football terms, Lyon will always be a suburb of Saint-Etienne

“In football terms, Lyon will always be a suburb of Saint-Etienne,” Rocher famously declared. At last the Stephanois could relax in the knowledge that they would always be better than Lyon at something. Or so it seemed.

The cure for present pain: the past

Patrick Revelli is feeling nostalgic as he stands, beer in hand, watching a replay of the 1976 European Cup quarter-final on a large television inside Le Chaudron Vert, one of his favourite bar-restaurants situated a stone’s throw from Saint-Etienne’s ground, Stade Geoffroy-Guichard.

They may have won five titles but we’ve won 10, and that’s three years in a row that they’ve lost in the Champions League quarter-finals

It is three days before April’s derby and despite Lyon’s recent title triumph, Revelli, the former Saint-Etienne striker now working in the club’s marketing department, is full of fighting talk. “Rocher once said that Lyon would always be a suburb of Saint-Etienne, and he was right. They still are,” he proclaims.

“They may have won five titles but we’ve won 10, and that’s three years in a row now that they’ve lost in the Champions League quarter-finals. I can tell you there weren’t many sad faces in Saint-Etienne the night they lost to Milan. In any case, Saint-Etienne can never be a suburb of Lyon. They’re in the Rhone, we’re in the Loire. There’s a natural border.”

The easiest way to forget about the present is to live in the past, and Revelli’s eyes quickly flicker back up to the screen where Les Verts are trailing 2-0 to Dinamo Kiev with time running out in the second leg. Patrick Revelli, not to be confused with older brother Herve, has come off the bench at half-time. He was already bald back then but his handlebar moustache has grown bushier with age. “Revelli looks fresher than the others. Maybe he can make the difference,” the commentator announces.

Revelli nods sagely. Soon he’s setting up his brother to score and give the French side hope. A handful of locals propping up the bar seem as captivated by the game 30 years on as the 40,000 fans were back then. The bar owner offers to put on his favourite Allez Les Verts CD as the excitement builds but Revelli declines, preferring to focus on events unfolding on the television. “Just look at those fans,” he says. “It was such an inspiring place for us to play and such a terrifying place for our opponents.”

NEXT: "France didn't qualify in '70 or '74, so we assumed the role of the national team"

The legend of Saint-Etienne stemmed from their heroic European comebacks. Perhaps the most memorable came in 1974 when, after losing the first leg 4-1 to Hajduk Split, they stormed to a 6-5 aggregate win.

By then Stade Geoffroy-Guichard was a renowned fortress and on that night – as smoke billowed into the air from the nearby factories and the fans sucked in goal after goal – it earned its nickname Le Chaudron: The Cauldron.

The comeback against Kiev wasn’t bad either and a big cheer goes up in the bar when Jean-Michel Larque fires home to send the game into extra-time. “Le Chaudron was the home of French football back then,” Revelli says proudly. “The whole country was behind Saint-Etienne and those Wednesday nights were unforgettable.

France hadn’t qualified for the World Cup in ’70 or ’74. Les Verts assumed the role of the national team

"People would travel from all over to watch our European games and those who didn’t come gathered around TVs with their friends. Don’t forget France hadn’t qualified for the World Cup in ’70 or ’74 so the people were starved of televised games. Les Verts assumed the role of the national team and every time we played it was a special occasion.”

Throwbacks to the glory days are scattered all around this themed bar. Shirts signed by famous former players like Johnny Rep, Michel Platini and Aime Jacquet hang on the walls alongside old newspaper cuttings and framed photos, including one of the Saint-Etienne players driving up the Champs Elysees in their green minis amidst swarms of supporters after losing the 1976 European Cup Final to Bayern Munich.

Johnny Rep: Part of the glorious team of the late ’70s and early ’80s, the Dutch striker won the French League in 1981, and made it to the final of the French Cup in 1981 and 1982.

Michel Platini: One of the all-time greats, the Frenchman midfielder stopped off in Saint Etienne on his way to superstardom, helping the club the League title in 1981.

Ivan Curkovic: The Yugoslav keeper made over 350 appearances during a nine-year stretch at the club from 1972, winning four League titles and three French Cups.

Dominique Rocheteau: Sharp of mind and quick of foot, the right-sided midfielder inspired Saint Etienne to three league titles, the French Cup and the 1976 European Cup Final.

The curse of the square posts

Somewhat tragically that 1-0 defeat at Hampden Park, still cherished as one of the most exciting, emotion-filled nights in French sporting history, looks destined to remain Saint-Etienne’s finest hour. Jacques Santini, the former Tottenham coach, and Dominique Bathenay both hit the Bayern crossbar with the game goalless, but – as any self-respecting Saint-Etienne fan will tell you – the ball stayed out because the goalposts were square rather than rounded. Saint-Etienne would never come so close again, losing to Liverpool in an epic quarter-final the following year.

But les poteaux carres (the square posts) have remained one of the hottest topics of debate in these parts (check out the fan website www.poteaux-carres.com for proof), and the national media continue to look back fondly at la fameuse finale perdue. Indeed the 30th anniversary of that game possibly received more media coverage than Lyon’s fifth title triumph this spring.

“We felt like we’d been cursed,” says a still-disbelieving Revelli. “The ball simply didn’t want to go in. Afterwards we just wanted to go back to Saint-Etienne where we knew our supporters would be waiting for us. But at the last minute we heard that a reception had been planned with the president on the Champs Elysees. It was all very surreal.”

Back in Le Chaudron Vert, eyes are glued to the television again... it doesn’t take a genius to work out that something is going to happen. Revelli jinks past a defender, bursts to the byline and cuts the ball neatly back for Dominique Rocheteau: “Et but!!!” screams the commentator. Les Verts have scored the winner in the 107th minute, the cheers go up in the bar and Revelli, three decades later, is receiving a series of pats on the back. Living in the past? It’s the best way to be if you’re a Saint-Etienne fan.

NEXT: "All they care about is hating Lyon"

"All they care about is hating Lyon"

“What do I really think of Saint-Etienne?” ponders Guillaume Amprino, president of Lyon’s biggest supporters’ group the Bad Gones (Bad Boys). “To be honest, I don’t really care. They make me laugh. Their supporters live in the past and all they care about is hating Lyon.”

For most Lyon fans, the great Saint-Etienne side of the 1970s is just something they have read about in the papers. Lyon did not have much support in those days and it is only in the last decade that their fan base has expanded significantly. The Bad Gones were founded in 1987 and most of their 2,700 members are too young to remember Saint-Etienne’s heyday.

Saint-Etienne didn’t even win the ’76 final... they lost and yet still paraded up the Champs Elysees

“We know they had a good side 30 years ago and we respect that, but 30 years is a long time,” Amprino points out. “I don’t mind the press and the supporters being nostalgic but what really bugs me is the fact that Saint-Etienne didn’t even win the ’76 final... they lost and yet still paraded up the Champs Elysees like winners! It’s just ridiculous and it says a lot about the French mentality – we love our honourable losers.”

The word loser rarely gets an airing in Lyon these days. “We’re lucky to have a president who has instilled a winning mentality, and now we’ve left Saint-Etienne behind. The derby’s still important, but our biggest games are against Manchester United, Real Madrid or Milan. For Saint-Etienne, the games against Lyon are their Champions League.”

Football is not all that has stagnated in Saint-Etienne. Taking a train from Lyon to Saint-Etienne is like travelling back in time. Gone are the air-conditioned TGVs that link Lyon with most of France’s main towns. Instead a rickety train rolls out of Part Dieu station, slowly leaving behind the leafy boulevards and the elegant buildings that line the banks of the Rhone.

The countryside between the towns is scattered with reminders of the industrial decline that hit Saint-Etienne so badly from 1976 onwards: disused factories, abandoned houses and farmyards dominate the landscape, interspersed with the occasional neglected football pitch.

Arriving at Chateaucreux station is hardly more uplifting. Saint-Etienne’s centre has been taken over by scaffolding, the streets are deserted and the town seems depressed. Finding the tourist office proves an impossible task despite the many signposts, and Le Cafe Vert (anyone spotted a trend?) on the main square is one of the few establishments open on this Thursday afternoon.

“The town has changed a lot since the 1970s,” reflects cafe owner Jean-Claude Faurel, taking a pause from his game of darts. “There used to be a real vibe when the factories and the mines were open and the football team was winning. People are trying to inject new life into the town with new projects, but in recent years the population has been dropping almost as quickly as Les Verts.”

NEXT: "Pathetic, loathsome and dishonest"

"Pathetic, loathsome and dishonest"

The team lost its way in the early 1980s and is yet to recover. Their famous youth academy that provided the cornerstone of the success ceased to churn out gems and a period of instability followed the departure of Rocher in 1982, allowing Bordeaux, Marseille, then PSG to enjoy periods of supremacy. Half an hour up the road, meanwhile, some sturdy foundations for success were being laid following Aulas’ arrival at Lyon.

Lyon have no class because their president is one of the most pathetic, loathsome and dishonest people on the planet

Like most people in Saint-Etienne, Faurel, a burly middle-aged man with shaven grey hair, has plenty to say about Saint-Etienne’s rivals. “Nobody here would deny that Lyon are a good team but they’ll never be a great team because they’ve got no class,” he declares. “The reason they’ve got no class? Because their president is one of the most pathetic, loathsome and dishonest people on the planet.”

Aulas has many enemies in France but nowhere is Lyon’s power-crazed owner despised as much as in Saint-Etienne. Lyon were a second division outfit lacking history and support when he took charge in 1987. But the ruthless entrepreneur has succeeded in transforming them into one of Europe’s strongest sides thanks to a combination of canny economic plans and bloody-minded determination.

The ultimate manipulator, Aulas has no qualms about unsettling rival clubs (as his public courting of PSG’s Pauleta and Marseille’s Franck Ribery proved this summer) and he has been known to stray from the truth on more than the odd occasion. “The day Lyon become a big club will be the day that Aulas stops lying,” Saint-Etienne’s ineffectual president Bernard Caiazzo fumed recently.

Aulas cemented his status as a figure of hate in September 2000. Les Verts were enjoying a promising renaissance at the time having gained promotion back to the top flight the previous year. Inspired by two Brazilian strikers, Alex and Aloisio, they were destroying opponents on a regular basis – the former even scoring four times in a memorable thrashing of Marseille.

But on the eve of an eagerly-anticipated derby, Aulas burst their bubble by letting slip that Alex and Aloisio, who had supposedly attained EU status in the summer, were playing under false Portuguese passports. The pair were immediately taken off the teamsheet, but it was too late for Saint-Etienne who found themselves embroiled in a scandal that rocked French football. They were relegated to the second division as punishment and would not be back until 2004.

The rivalry between the clubs used to be a fun, sporting rivalry, but because of Aulas it’s turned nasty

“The rivalry between the clubs used to be a fun, sporting rivalry, but because of Aulas it’s turned nasty,” claims Faurel. “He’s a very sad, vindictive man. It’s good to want to be successful but not at any cost. Grassing up your neighbour like that is unforgivable.

"If he just did his job and stopped sticking his nose in everybody else’s business, he might find himself a little less hated. Now we’re just waiting for him to make a false move. It’s only a matter of time before somebody uncovers some dirt on Aulas, then it’ll all be over. Lyon will disappear as quickly as they emerged.”

For the time being that seems wishful thinking. Lyon’s rise would appear to stem mainly from sound economics rather than underhand dealings and, in any case, Aulas – as the president of a G14 member and the vice-president of the French League – is now the most influential man in the French game.

Lyon's European failure is Etienne's glory

At Saint-Etienne it took us 12 years of playing in Europe to get to the final. It’s a slow process

Lyon’s domination looks set to run and run and a sixth straight title is very much on the cards. Houllier now has such a strong squad that his reserves would probably beat the second-best team in France. Winning the Champions League represents a more demanding challenge but one that may soon be within their grasp.

“They’ll get there in the end,” Revelli, who has managed to drag himself back into the present, predicts glumly. “At Saint-Etienne it took us 12 years of playing in Europe to get to the final. It’s a slow process. Lyon are on the right track, though, they’re learning all the time and the breakthrough will come eventually.”

In a complete reversal of fortunes, Saint-Etienne are now the ones glued to their television sets on Champions League nights, watching enviously as Lyon spar with Europe’s elite. “It’s not nice but we have to accept it because it’s unlikely that Saint-Etienne will finish above Lyon in the near future,” Revelli admits. Understandably the former Saint-Etienne striker struggles to muster the same kind of enthusiasm when talking about the current side.

The Stephanois are braced for another season of mid-table mediocrity, although even that might be tolerable if Lyon come up short again in Europe and Les Verts regain some local pride with a derby win.

“It’s vital that the players give absolutely everything in the derby,” Revelli says firmly. “Then the fans will be happy. The problem is that these days the players are too nice. I’m shocked when I see a Saint-Etienne player helping a Lyon player to his feet. Recently I even saw one of our players swap jerseys with a Lyon player at half-time! That kind of behaviour is unacceptable. It would never have happened in my day.”

Unfortunately for Revelli and Saint-Etienne, times have changed. As they’re beginning to understand only too well…